It’s easy to be skeptical of a project like X-Men ’97, a show that blatantly taps into nostalgia for pop-cultural ephemera from millennial childhoods. But gradually, ’97 proved its revisitation of X-Men: The Animated Series was genuine, a thoughtful continuation of its story to new and quite fascinating places, earnestly adopting the earlier show’s vivid look and tone while doubling down on mutantdom as queer allegory. It also covers a lot of ground in adaptation, barreling through a half-dozen landmark issues and crossovers in a rollicking, delightful ten episodes.

That speed was compelling — there was no telling how far the next episode would go — but it means there’s still plenty to explore in the comic books the season was based on. Some of the most famous stories had already been done, but the X-Men have an incredibly expansive history of fighting for a world that hates and fears them, so there’s a lot to pull from. ’97 was surprising in doing so, the second half of its season drawing from the crossover Operation: Zero Tolerance, which has been relegated to the “X-Tra Credit” section of our list because, well, it’s not all that fun to read.

For anyone who wants to start at the beginning, the best thing to read is Giant Size X-Men, No. 1, and then Uncanny X-Men, No. 94, and go from there; those comics essentially form the X-Men as we know them. Otherwise, here are some of the major stories X-Men ’97 adapted as well as ones the showrunners seem to be hinting at with teases for a second season — all issues to fill the void Children of the Atom left behind.

HERE COMES (what you’re going to read) TOMORROW

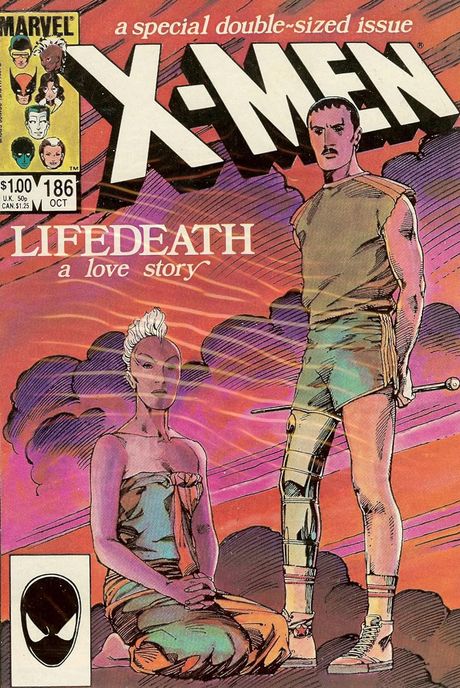

“Lifedeath” (Uncanny X-Men, No. 186)

Perhaps the story most shortchanged by X-Men ’97’s breakneck pacing, the bumper 186th issue of Uncanny X-Men dedicated most of its 40-plus pages to a story of rehabilitation. Storm loses her powers while protecting Rogue, thanks to a “neutralizer” gun built by Forge, a mutant with superhuman intellect who has loaned his talents to the government. This happens in in Uncanny, No. 185, but Forge recaps in detail here. Unlike on the show, Storm remains powerless for quite some time afterward.

The “Lifedeath” issue itself, created by writer Chris Claremont and co-writer–penciller Barry Windsor Smith (Monsters, Weapon X), is beloved for its willingness to slow things down. Its first half comprises about 16 nonstop pages of just two people talking about the parts of themselves they have never shared with anyone else. (There’s also an alien invasion, but that’s the B-plot).

It’s a pivotal moment for Claremont’s arc about bringing the Weather Goddess back down to earth. During the issue, we’re often reminded of Storm’s life on the streets as a pickpocket before her powers awakened and she became worshipped; the punk look is part of what Forge calls “a more human passion” to how she conducts herself in the present. An exchange between the two summarizes the double-edged sword of her disempowering: “I could fly! I was one with all creation!” she complains to Forge, who cooly responds, “And now you’ve got to walk, like everybody else.” It’s part of a realization that she became defined by her powers — she was living half a life because she suppressed her emotions, a track that runs parallel to the way Cyclops becomes consumed by his duty as an X-Man, which curbs his potential happiness with Madelyne Pryor (more on that later).

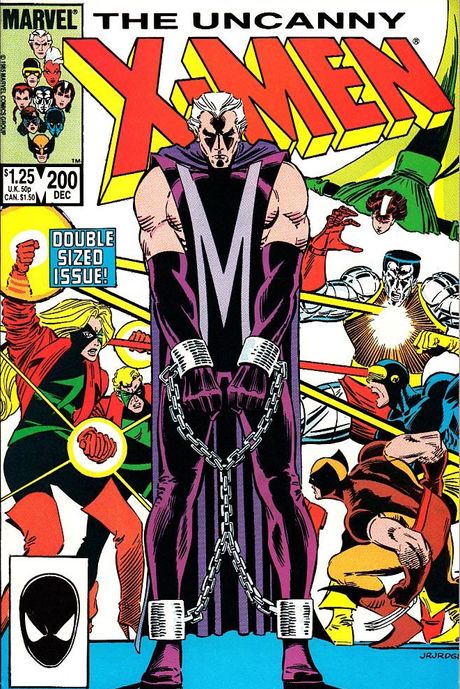

“The Trial of Magneto” (Uncanny X-Men, No. 200)

One of X-Men ’97s strongest episodes is its second, “Mutant Liberation Begins,” which basically adapts Uncanny X-Men, No. 200, “The Trial of Magneto,” written by Claremont with pencils by John Romita Jr. It’s a thorny and complex story, as many Magneto-centric tales are: It opens with a narration full of the press’s gross hyperbole in covering the trial, referring to Mags as “the epitome of evil, the greatest fiend since Adolf Hitler,” while claiming “his origin is unknown” when it’s later confirmed to be on record that Magneto is a Holocaust survivor.

The trial inspires anti-mutant sentiment as well as an onslaught of antisemitism and misogyny toward the defense. Claremont’s equivocation of mutantdom with real-world identities and conflict is often indelicate (something the show has smoothed over somewhat), and the same is true of “The Trial of Magneto.” Its flowery language combines real-world horror with fantastic nonsense (a statement from the defense reestablishes why Magneto is still so youthful — he got turned into a baby a little while ago).

Despite its more blunt elements, it’s a great chapter and the beginning of a fascinating face turn for the Master of Magnetism. Maddy goes into labor and Xavier is dying and maybe has to go to space at the same time as the trial — the same vague touchstones as the show but with different nuances. And most important, Xavier asks his old friend to give his dream a chance, to take over his school and help guide the young generation of mutants, though here we see it as a direct request rather than a surprise. Followed by an issue in which Cyclops and Storm duel to decide who leads (she trounces him without powers), it’s a landmark story that spurs an exciting period of change.

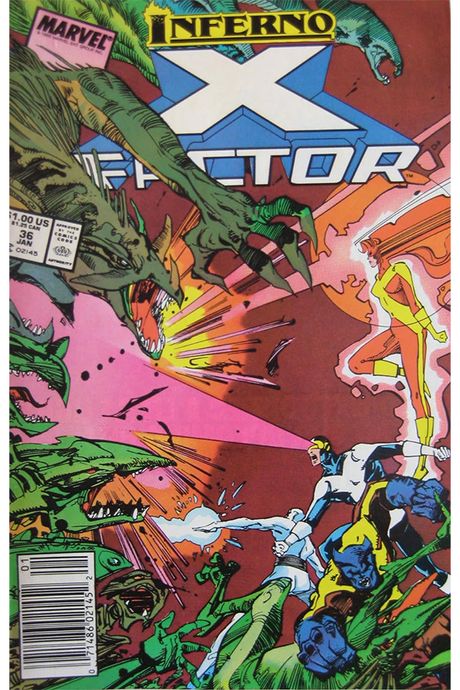

“Inferno” (Uncanny X-Men, Nos. 239–243; X-Factor, Nos. 36–39; New Mutants, Nos. 71–73; X-Terminators, Nos. 1–4)

The chaotic sprawl of the “Inferno” crossover is strikingly different from the compressed haunted-house episode of X-Men ’97, “Fire Made Flesh.” Written by Claremont and the great Louise Simonson, it also centers on the vengeful rampage of Madelyne, Cyclops’s wife and the mother of his child, but has a number of other (X) factors at play, such as the involvement of Illyana Rasputin (a.k.a. Magik), who is confronted by her traumatic past with the same hell dimension with which Madelyne now co-conspires.

Madelyne was retconned from just looking uncannily like Jean into being her actual clone, created by Mr. Sinister. Upon finding out Jean is alive, Cyclops ditches his family and begins “X-Factor,” a team comprosed of the original five X-Men, in a series written by Simonson. The team in Uncanny X-Men, presumed dead, now operates out of Australia.

While on that Outback team, Madelyne is understandably furious about how she has been treated, and the demons N’astirh and S’ym take advantage of this, orchestrating her transformation into the witchy “Goblin Queen” who then assists with a demonic invasion of New York from the hellish Limbo dimension, igniting a spooky and often very funny crossover that begins with an elevator eating a family and other inanimate objects soon joining the fray. The episode captures some of its existential horror and gothic madness in microcosm at the X-Men’s home base at the school, while the surreal artwork of “Inferno” sees the Summers’ soap opera drag the entirety of Manhattan and the X-Men line to hell in a fun, often horrific collection of parallel stories. In short, things ended a lot more amicably in ’97.

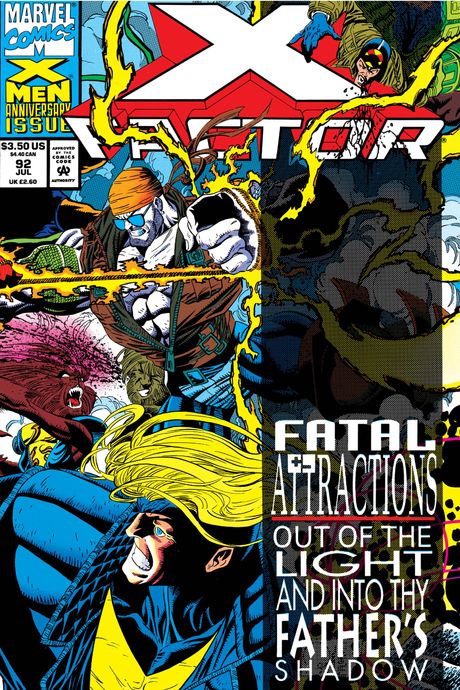

“Fatal Attractions” (X-Factor, No. 92; X-Force, No. 25; Uncanny X-Men, No. 304; X-Men Vol. 2, No. 25; Wolverine Vol. 2, No. 75)

The 30th-anniversary crossover “Fatal Attractions,” published in 1993, is an encapsulation of the thoroughly mixed bag X-Men comics were at the time. From convoluted beginnings in X-Factor, No. 92, and X-Force, No. 25, the main drama of the arc comes from how, as in the show, Magneto reverts to his old ways, a heel turn that felt a little disappointing on the page. As he builds a base he calls Avalon in Earth’s orbit, this time he’s followed by a group of fanatics called the Acolytes featuring the then-new character Exodus. As in the show, Magneto attacks Earth with a giant electromagnetic pulse, and an X-Man defects (not in that order). But it’s Colossus who joins instead of Rogue, spurred on by his sister Illyana’s dying from the Legacy virus in Uncanny X-Men, No. 303. It’s still an interesting story for all the moral lines being crossed, with palpable unease when Xavier resolves to kill his oldest friend.

Everything feels excessive — from the big hair, big shoulders, and big bulky costumes in the character designs to the moment when Wolverine has his adamantium skeleton ripped out of him in X-Men, No. 25. Even though some of the issues feel overly talky and a bit superfluous, it’s full of memorable and expressive art and some great emotional highs, especially Wolverine’s tender farewell to Jubilee as he leaves the team.

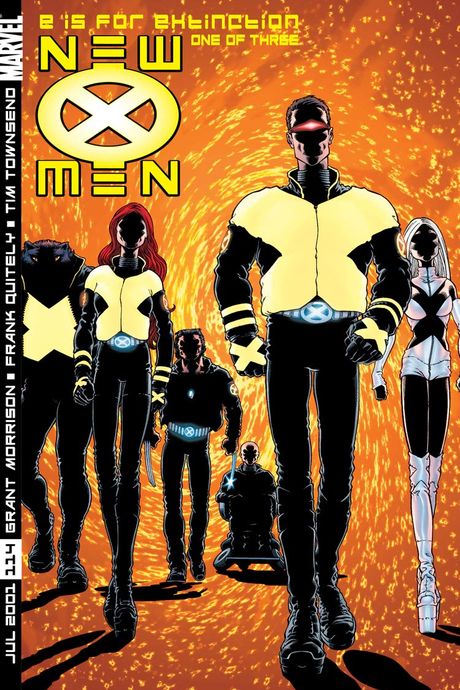

“E Is for Extinction” (New X-Men, Nos. 114–116)

In the shocking fifth episode of X-Men ’97 the mutant island nation of Genosha is destroyed, its festivities soon turning to genuinely unsettling panic. It’s the season’s best episode — if its most disturbing — and it was adapted from the beginning of Grant Morrison’s storied New X-Men, the arc titled “E Is for Extinction.” The show sets up the plot as the doing of Bastion by way of Mr. Sinister, but in the comic, it’s even more outlandish with the blame belonging to Charles Xavier’s evil twin, Cassandra Nova — actually a psychic remnant of her because he killed her in utero. Some other elements from later in Morrison’s run make their way into the episode, such as Scott having a psychic dalliance with Madelyne. In the books, it’s Emma Frost, which makes her sly nod of approval on the show funny on a meta level.

Rather than a midseason twist (and something of a surprise to comic-book readers in that it’s pushing into stories from the aughts for its source material), the destruction of Genosha is the fuse for the bomb Morrison threw into the X-Men’s status quo. New X-Men was a massive visual and narrative shake-up, a much-needed reset after the rather uneven stories of the ’90s. It stuck to the familiar surroundings of the mansion-school but added some fascinating wrinkles to familiar characters, and I’m not just talking about Frank Quitely’s rugged penciling. The team is a little smaller, some old foes (Emma, who gets her diamond powers at this point) are brought into the mix, and the bright-yellow spandex is gone. And while the show may mock the black leather uniforms — though that’s more related to the Fox films — those outfits look cool as hell here.

FUTURE, PAST (some other books that could pop up next season on X-Men ’97)

The Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix, Nos. 1–4: Here you’ll find time-travel shenanigans with Scott and Jean, who are transported into a strange dystopian future (in different bodies) by Mother Askani (an elderly, also time-displaced Rachel Summers, glimpsed in the ’97 season finale). Rachel leads a resistance group called the Askani, modeled after the X-Men, and has been helping to raise her sort-of half-brother, Nathan, who may be a key player in defeating Apocalypse, now a despot ruling Earth in this far-flung time. A follow-up miniseries, Askani’son, follows Nathan’s adventures in this setting. A sequel, The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix, is illustrated beautifully by the late John Paul Leon. The stinger of the show’s season finale, “Tolerance Is Extinction: Part 3,” seems to point toward some combination of this arc and Rise of Apocalypse, Apocalypse’s origin story in ancient Egypt.

“The Blood of Apocalypse” (X-Men Vol. 2, Nos. 182–187): Gambit becomes the Horseman of Death, something teased in the post-credits of “Tolerance Is Extinction: Part 3.” Some other former X-Men accompany him.

Age of Apocalypse: A fun crossover that, if adapted, would represent a full-circle moment for the show in that the comics were actually inspired by the animated series.

Onslaught: The consequences of Xavier’s attack on Magneto in “Fatal Attractions” spin out into this crossover. With the resolution between Xavier and Magneto seen in the finale, it feels less likely to happen. But it’s not a good crossover, so probably better to wait and see if X-Men ’97 pulls the trigger on it.

X-Cutioner’s Song: A crossover with story roots in the events of The Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix with the main villain being Stryfe — a clone of Nathan created by the Askani in case they can’t deal with his Techno-organic virus.

X-TRA CREDIT: Further Reading (hope you survive the experience)

Operation Zero Tolerance was adapted as a significant part of this season’s second half with the villain Bastion and his Prime Sentinels. This story was done better in the show by a pretty large margin.

Second Coming: Bastion’s entirely metallic and winged final appearance comes from this crossover — in those comics, he kills Nightcrawler, so their fight in episode ten was a real close call.

It’s pretty well known that the visual basis for X-Men: The Animated Series and X-Men ’97 is X-Men Vol. 2, the look defined by the art of Jim Lee (who would also take over from Claremont as writer for a little while). This is where the Blue and Gold team monikers, used in “Tolerance Is Extinction,” come from.

X-Factor, Nos. 65–68, “Endgame”: Following a conflict with Apocalypse, Scott and Jean send young Nathan to the future to give him a chance against the Techno-organic virus that’s killing him — this element is folded into the X-Men ’97 episode “Fire Made Flesh.”

Regarding “Lifedeath,” there’s a follow-up issue, “Lifedeath II” (Uncanny X-Men, No. 198). It’s more volatile than its predecessor, continuing Storm’s psychological journey after her disempowering, but it turns into an environmentalist story about the precarious balance between the worlds of technology and nature. Similarly, Uncanny X-Men Annual, No. 9, “There’s No Place Like Home,” sees Storm wielding thunder-god powers courtesy of Asgard for a little while.

It’s worth checking out the Uncanny X-Men comics known as the “Outback Era,” in which the team operates out of Australia while being presumed dead — still a potential path in the show should the team split from Xavier. This rather unique status quo begins in Uncanny, No. 229, as the aftermath of the “Fall of the Mutants” crossover.

Likewise, continuing Morrison’s run on New X-Men is also a treat with some great issues (like my personal favorites, the silent issue, New X-Men, No. 121, and one focusing on Xorn in New X-Men, No. 127), which have been homaged more than a few times. While Morrison’s run on the comic later lands on some downright baffling decisions (mainly to do with the characterization of Magneto), it speaks to the quality of the series that it weathers such weird twists (and the occasional bit of off-putting art).

Speaking of which: Jonathan Hickman’s reboot of the X-Men line with House of X and Powers of X (that’s “Powers of Ten”) is the freshest the mutant stories have felt in years. This era is coming to an end next month, so it’s a good chance to explore it from start to finish.