Brontez Purnell, at 38 years old, is already something of a Bay Area legend. If you grew up in the recent Oakland punk scene, you’ve probably seen him play a show with his garage rock band the Younger Lovers. If you follow queer zine culture, you probably have at least a few copies of Purnell’s zine Fag School, which he’s been writing since the early aughts, or read one of the books he’s put out with small publishers. You might have watched his art-house soft-core porn film 100 Boyfriends Mixtape or seen him perform contemporary dance. But most people in Purnell’s world know him as Oakland’s daddy — something of a watchful protector over the gentrifying city, attuned to (but never too involved in) the affairs of the small scene. “I literally represent the 0.0001 percent,” says the artist, who grew up in Alabama. “Black queer men that have been riding around on a bike in the California sunshine for almost 20 goddamned years.”

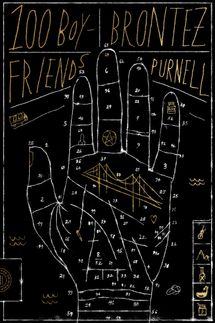

On February 2, Purnell is releasing his first book with a major publisher, the MCD x FSG Originals imprint: 100 Boyfriends, a novel composed of vignettes on love, sex, and Purnell’s love of love and sex. It fluctuates between first person and third person, the present and the past, prose and poetry, and reads like a series of 4 a.m. text messages received from a very smart and very messy friend — when there’s no way you can wait till morning to respond, “What the fuck? Are you OK? Did you at least have fun?” If Purnell is a living archive of the Bay’s queer and punk scenes in last two decades, 100 Boyfriends is an autofiction anthology of drug-fueled warehouse dwellers, queer skate kids, and regretless heartbreakers.

I spoke to Purnell on one of the last warm days of Bay Area autumn, while we sat on the back deck of his Victorian house in Oakland. He shared how he conceives love for the page, what it was like to work on 100 Boyfriends, and why he just can’t stop making art. —Saam Niami

Growing Up, Again

I was a zine kid in the ’90s — I started writing zines when I was about 14 years old. I never really felt that there was a hope or a life or a context for me down South. And so when I got to Oakland, I just felt for all the mistakes, all the crazy shit, everything that happened. It really was a breath of fresh air just to set foot on the soil. I was so developmentally regressed when I got here at 18, I essentially had to come and have my for-real teenage years — life was so repressive in Alabama. My mother never really let me out of the house because I was too Black and punk and queer. She was afraid somebody was going to fucking kill me. So when I got here, I really had to just grow up in a really intense way. I had guides, but I didn’t have any parents. I really had to rely on myself as a moral compass.

It was really fucking intense, but I wouldn’t trade that shit for nothing in the world. It’s all a patchwork quilt or a blanket: You remove any one thread, it dissembles the whole blanket. If I could talk to my younger self, I wouldn’t go up in that kid’s face telling them what to do. I’d just be like, “Bitch, it’s going to be really fun and really hard. Go ahead.”

There were so many wild, public displays of hedonism back then. If you did that shit these days, these kids would call you out on the internet so fast. But I wanted to be in that scene. We did these things because we were punk. Because we were crazy, radical queers. We came to these things because we were fucked up, because our parents were drug addicts or neglectful conservatives. We were trying to escape it and we let our trauma ricochet off of each other. But also, deep within it, there was a sense of love.

All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

My book, 100 Boyfriends, doesn’t really deal with a hundred boys — that just sounds like a horrible rom-com. It’s really about how, every time you date someone, you’re left with a ghost of someone, and that person’s left with the ghost of someone, and we’re all just carrying around the baggage of everyone’s relationships, even when we deal with each other. There’s this line in the book that goes: “Between two men, there can be a hundred ghosts in the room.” It’s about dealing with the residual effects of entanglement.

When I write about a real experience, it depends on where I’m calibrating from because I have theater IQ. Maybe it’s all about the physical space — a bedroom where you see every single squiggle mark on the ceiling. Whenever you’ve broken up with someone, what do you remember from that day? Do you remember if it was sunny? Do you remember cologne, perfume, or a smell, or a meal you ate? Or maybe you just strictly orient from an emotion you felt. There are lots of insertion points for memory. You can be as sacred or as secular as you want.

I think the older I have got, I don’t approach relationships at all. I just exist and things happen. If you call that a fucking very earned weariness, then sure, you can say I’ve changed. That gusto, that do-or-die love — “I have to be with this person. My heart and whole being is going to fucking break in two if I don’t have this person” — I haven’t felt that way since my goddamned 20s. But then, you know, 100 Boyfriends is definitely more for, you know, old jaded whores. It’s about the time after that first feeling has passed.

On Going Legit

I’ve never had this much parental intervention. When you’re in the cut of DIY art for years, you’re like, “No one’s supporting this. I got to do all this myself. I gotta make sure all this shit is doing it.” But then when I got up in FSG’s house, I was not ready — because one page would have like 12 questions: “Well, what do you mean by this? How do you mean this? Maybe we can say it this way.” Blah, blah, blah. And I’m like, “Oh shit, this is what it means to professionalize now.” Almost wasn’t ready for that shit. But I think you should be able to approach any language and find where you vibe with it. Plus, who knows about ever getting this chance again? So, you know, I stuck with it.

I like zines and I like something episodic and periodical, which is why I still do Fag School. I think it’s always good to go back every couple of years and reevaluate how you feel about something — state what you’ve learned.

Alternate Destinies

At the end of the day, my band, the Younger Lovers, has never been a heavily supported thing. It’s a pop-punk band, but it’s too Black and too queer. It’s something that I do as a labor of love. I think most people in Oakland would just remember it as the band that played for free at all the warehouses for years.

I would have to say the Younger Lovers is more of a global scene. When people are like, “Oh, I love the Younger Lovers,” it’s always some random person from the Philippines or some dude from France. I’ve gotten more congratulatory remarks from people way outside the bubble than I ever did inside the bubble.

My problem with Oakland is just that it really can be a slacking-ass, beer-drinking town. Considering how much money we pay to live in this motherfucker, it makes sense that there’s not a lot of support. I’m not bitter or angry about it because, at the end of the day, I see what most garage rock bands have to do. If anyone wants to tour the Younger Lovers and sit me in a fucking Trump state, with me talking all the shit that I do, the only thing they gonna do is lynch my Black ass. So it’s probably better that I just make some music in a garage in Oakland and, you know, keep it moving.

If it had been up to me, I would have gotten all my rock-and-roll accolades at 24, and I would have gladly OD’d at 26 and just left a beautiful corpse. But it wasn’t up to me. God was like, “No, your fat Black ass going to keep working forever and ever. Amen.”