Carl Reiner’s first boss in television, Sid Caesar, wrote in his book Caesar’s Hours that Reiner “was a comedian himself, and he truly understood and still understands comedy.” Reiner, who died Monday night at age 98, worked as a writer, producer, and director, but when it comes to his work as an actor, he is perhaps best known as a straight man. Working alongside Caesar on Your Show of Shows, he was often the anchor that grounded the star’s huge comedy moments and cartoonish “double-talk” accents. The Dick Van Dyke Show was originally scripted as a starring vehicle for himself, but he stepped back, rewrote, and gave himself a bit part as the egomaniacal Alan Brady. And then there’s his work with Mel Brooks.

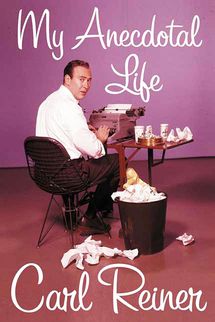

The duo met in Caesar’s writers’ room in 1950, and together they forged a friendship that continued until Reiner’s last days. In their later years, the pair ate dinner and watched movies together nightly. Decades earlier, they were the dinner entertainment as they performed their then-private comedy routine, the 2,000-Year-Old Man, for friends and celebrities. In his 2003 memoir, My Anecdotal Life, from St. Martin’s Press, excerpted below, Reiner discusses his friendship with Brooks, Jewish humor, the origins of the routine, and its evolution from private joke to the hottest record in Buckingham Palace.

When I met Mel Brooks in 1950, we were both working on the venerated television program, Your Show of Shows. I was a twenty-eight-year-old actor, and Mel, the youngest member of a brilliant writing staff, assumed he was twenty-four. Had I not watched a Sunday night television program, We the People Speak, Mel Brooks would never have discovered his true age.

We the People Speak was a weekly news program hosted by Dan Seymour. Each week, using actors to impersonate the people making the news, they would dramatize the important events of the week. What I heard one Sunday night was, I thought, appalling and begging to be satirized. It seemed like a perfect vehicle for Sid Caesar. I could not wait to discuss it with Sid, the writing staff, and Max Liebman, the boss of us all.

No one had seen the show, so that Monday, in Max’s office, I did a re-creation of one of their re-creations of the news.

“Ladies and gentleman,” I said, mimicking Dan Seymour’s delivery, “the voice you are about to hear belongs to a plumber who was in Josef Stalin’s toilet. While fixing a faucet in the washbasin, this is what the plumber overheard: “… and I hear Stalin say,” I reported, using a Russian accent, “I’ve goink to blow up vorld Turrsday!’ ”

I know you are shaking your head, but I stand by that quote. Everyone in Max Liebman’s office — Max, Sid Caesar, writers Lucille Kallen, Mel Brooks, and head writer Mel Tolkin — was sure that I had made it up. I remember saying that if Stalin actually said that, shouldn’t Dan Seymour tell President Eisenhower or the Congress about it before scaring the crap out of everyone in America who owns a seven-inch, black-and-white television set? And then to illustrate how utterly ridiculous the whole premise was, I pointed to young Mel Brooks.

“Here with us today, ladies and gentlemen,” I announced à la Dan Seymour, “is a man who was actually at the scene of the Crucifixion, two thousand years ago. Isn’t that true, sir?”

Mel, aging before our eyes, sighed and allowed a sad “Oooooh, boy” to escape from the depths of his soul.

Here now is the moment Mel Brooks and the world discovered that a two-thousand-year-old man was living inside the body of a handsome, twenty-four-year-old comedy writer. I use the word handsome objectively. I know Mel will not be upset if, when writing about him, I stick to the truth.

I pressured the Old Man and asked, “You knew Jesus?”

“Jesus … yes, yes,” he said, straining to remember, “thin lad … wore sandals … always walked around with twelve other guys … yes, yes, they used to come into the store a lot … never bought anything … they came in for water … I gave it to them … nice boys, well-behaved… .”

For a good part of an hour Mel had us all laughing and appreciating his total recall of life in the year 1 A.D. I called upon Mel that morning because I knew that one of the characters in his comedy arsenal would emerge. The one that did was similar to one he did whenever he felt we needed a laugh break. It was a Yiddish pirate captain who had an accent not unlike the 2,000-Year-Old Man.

“I’m stuck in port,” the pirate captain would complain, “I can’t afford to set sail. Do you know much they’re asking for a yard of sail cloth? It doesn’t pay to plunder anymore!”

Starting that day in Max’s office, and continuing for ten years, I would ask Mel to channel the Old Man, and he would oblige by telling us things that made us laugh and, later, our wives, when we came home and repeated “what Mel said” that day. The Old Man became so popular that dinners in diverse places like New Rochelle and Fire Island would be built around the Old Man’s availability. The most successful dinner parties we have ever given or attended were the ones Mel Brooks attended and shared his firsthand knowledge of all the important people and events of the last five millennia. Yes, I did say five millennia. …

Among an elite circle of friends who enjoyed laughing until their sides hurt and nausea overtook them, the Old Man was completely known and the most sought-after dinner invitee on both coasts. Since I was concerned that my probing questions and Mel’s brilliant ad-lib answers might be lost to posterity, I bought a portable Revere, a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and taped all of our sessions.

During the ten years Mel and I had performed at people’s homes, we were continuously asked why we had not made an album of this hilarious stuff.

A word now about why we held firm about not commercializing the 2,000-Year-Old Man.

In the 1920s and ’30s, there were wonderful comedians and comediennes whose material and performances were enhanced by their speaking with a Yiddish accent. In vaudeville there was Smith and Dale; in burlesque Eugene and Willy Howard; on Broadway Weber and Fields and Fannie Brice (a star of the Ziegfeld Follies); on radio Mr. Kitzel, and a Mr. Shlepperman on The Jack Benny Show; Bert Gordon (the Mad Russian) on the Eddie Cantor Show; Mrs. Nussbaum on the Fred Allen Show; and Gertrude Berg and Eli Mintz on The Rise of the Goldbergs. The Yiddish accents they employed were all reminiscent of how Middle and Eastern European Jewish immigrants spoke English. Their accents were considered to be cute, charming, and funny, but when Adolf Hitler came along and decreed that all Jews were dirty, vile, dangerous, subhuman animals and must be put to death, Jewish and non-Jewish writers, producers, and performers started to question the Yiddish accent’s acceptability as a tool of comedy. The accent had a self-deprecating and demeaning quality that gave aid and comfort to the Nazis, who were quite capable of demeaning and deprecating Jews without our help. From 1941 on, the Yiddish accent was slowly, and for the most part, voluntarily, phased out of show business.

Growing up in Brooklyn and listening to his uncles, his neighbors, and the shopkeepers talk and argue, Mel, blessed with a good ear for music, had no difficulty absorbing the lilting, Middle European Yiddish accent. Mel and I were very aware that our friends and fans were, for the most part, Jewish, and if they were not, they laughed and behaved as if they were. We were also under the impression that only New Yorkers or urban sophisticates would know what the Old Man was talking about or find it so funny that they would double over with laughter. Our audiences were always small, always select, and always happy to hear the Old Man tell intimate stories of his involvements with Joan of Arc, Helen of Troy, and Murray, the discoverer of ladies.

The album was well reviewed, but Mel and I still worried about its broad appeal. Half of the album was Mel performing many different characters. We were sure everyone would find them funny, but the title half was all the Jewish-accented Old Man. Would WASP America get him? Would Christians find the old Jew funny? Do “our people” still consider the Yiddish accent to be non grata? The highly successful appearances Myron Cohen made on the Ed Sullivan show spinning hilarious ethnic tales was a good indication that the Yiddish accent was again becoming grata.

Our unlikeliest fan, Cary Grant, gave us a hearty vote of confidence very early on. At the time of the release of the record, I was working for Universal Pictures writing the screenplay that Ross Hunter knew I had in me, The Thrill of It All for Doris Day and James Garner. Universal had given me a big, comfortable bungalow right next door to Cary Grant’s bigger one. He popped in one day, introduced himself, which is something Cary Grant never need do. I immediately gushed like a teenager and told him how much I loved his work and a lot of other things he had heard too many times. As he was leaving, I presented him with a copy of our album and told him to “pop by anytime” … and darned if he didn’t. He couldn’t have been more effusive in his praise of Mel’s 2,000-Year-Old Man. He laughed as he repeated a line or two of the Old Man’s dialogue, often answering “jaunty-jolly” when asked how he was feeling. He was so intrigued with the 2,000-Year-Old Man that he suggested we do another album and include “a two-hour-old baby who can talk.” On our second album there is a two-hour-old talking baby. Who is going to say no to Cary Grant?

When he left my office that day, he asked how he might get a dozen or so albums to give out to his friends. Naturally I was happy to have the albums delivered, complimentary of course, Cary Grant’s favorite way to shop. Twenty years after leaving MGM, he still brought them his weekly laundry.

For the next few weeks, Cary would phone from time to time to report on the wonderful reactions he was getting from his friends, and add, “Ahh, Carl, would it be possible to get another dozen or so?” I was thrilled to oblige, and I was even more thrilled to hear that famous voice talking to me! The last call on this subject was the one that forever set to rest any concerns we had about our album. Prior to that last call, Cary had asked if he could have two dozen albums delivered to his office as he was flying to London for a few days and wanted to give them out to his British buddies. I did remark about the possibility of his buddies “not getting it” and he pooh-poohed my concern. “They do speak English,” he reminded me.

A week later Cary Grant and I had this conversation.

CARY

Carl, the album was a smash! Everyone loved it!

CARL

Who is everyone?

CARY

Everyone one at the Palace.

CARL

Are you talking about Buckingham Palace?

CARY

Of course …

CARL

You … You played The Two Thousand Year Old Man at Buckingham Palace?!

CARY

Yes, and she loved it!

CARL

Who’s she?

CARY

The queen. She roared.

This story and the dialogue, like 96 percent of this book, is absolutely true.

Well, there it was, the definitive word on the subject. Who is more non-Jewish, more Gentile, more WASP-like Christian, more 100 percent shiksa than the queen of England? Talk about broad appeal!

Not only was the album well received but it was nominated for a Grammy, which it didn’t win. Because the Old Man and his Pesterer hung on and continued to record, their last effort, The 2,000-Year-Old Man in the Year 2000, was awarded the Grammy that eluded them forty years earlier. I am hoping that after Mel Brooks helps to launch the planned ninety-four domestic and foreign productions of his phenomenal hit The Producers he will escort the Old Man to his neighborhood recording studio and let him go for a second Grammy.

As you may have gathered, I am very fond of Mel and his brain. On the lecture circuit, I borrow liberally from my friend’s brain. I quote him often and to excellent effect. Until recently, I was certain that Mel had never quoted me or had a need to. However, a month or so ago, I called his home and got his answering machine. It was Mel’s voice saying just three words, “Leave a message!” I was surprised — he had appropriated the message I had been using for years, which was, “Please leave a message.” His was one word shorter than mine, and I think ruder, but the fact that he thought enough of my message to appropriate it, was for some reason strangely satisfying.

From My Anecdotal Life by Carl Reiner. Copyright © 2003 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.