Around 8:40 p.m. last Saturday night, as Drakeo the Ruler walked toward a stage where he was scheduled to perform, a group of more than 40 men, many masked, swarmed him. It happened in what should’ve been a secure area of Exposition Park, where Live Nation was throwing Once Upon a Time in L.A., a one-day festival headlined by Al Green, Snoop Dogg, and YG, among others. At least one assailant stabbed Drakeo in the neck. As he lay bleeding on the ground, waiting for an ambulance to arrive, eyewitness footage of his ravaged body seeped onto the internet. Premature memorials and instant theories about who was responsible spread; there was gloating on Instagram. By the time his death was confirmed to family members roughly four hours later, the surreality had hardened into something more concrete. Drakeo the Ruler was dead at 28.

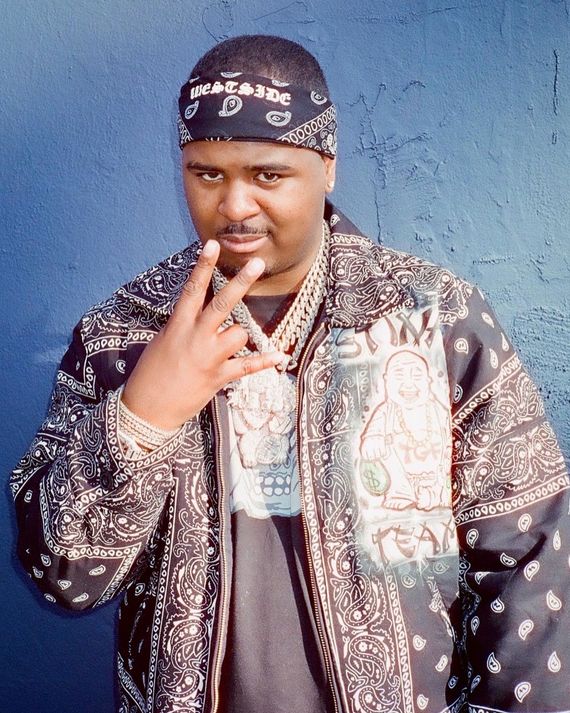

At the time of his death, Drakeo, who was born Darrell Caldwell and raised some 60 blocks south of Exposition Park, was one of the best rappers in California and certainly one of its most influential. He was a pioneer of the careening flows that pushed underground rappers in L.A., the Bay Area, and Michigan past traditional bar breaks and into the avant-garde; his baffling latticework of slang remade the language, and the flagrantly digital beats he preferred became standard for his subgenre. He accomplished all this despite losing more than three years of his creative prime to incarceration — including the nine months he spent in solitary confinement at Men’s Central Jail in downtown L.A. There is a level on which Drakeo’s life and death work as a metaphor for a variety of systemic horrors. But any comparison can only be carried so far: The man, like his music, was singular.

Drakeo first participated in L.A.’s hip-hop scene not as an MC but as a dancer. This was toward the end of the 2000s, when jerkin’ had become the dominant strain of rap among young Angelenos. Jerkin’ grew out of gang culture as its pastel, skinny-jeaned release valve, its songs excuses for or instructions on its dances, which were captured on YouTube and amended by each successive crew. Drakeo and his high-school friends established their own clique, dancing at house parties and outside their school. While jerkin’ was relatively short-lived (though, eerily, is having revival on TikTok this month), it inspired his earliest recorded freestyles. Just as crucially, it established his place in the social pecking order — with hindsight, it is obvious he would be the one leading his friends to their next aesthetic home.

As the 2000s became the 2010s, jerkin’ gave way to something adjacent but a little meaner. Ratchet music, which was similarly minimal but folded in percussion from Louisiana and the base urgency of L.A. strip clubs, gave the city’s rappers new teeth. The sound is best exemplified by My Krazy Life, YG’s Def Jam debut from 2014. YG had been one of jerk’s aspiring stars, but as that scene fizzled, he and DJ Mustard perfected the bouncing snarl that would break him nationally. Many ex-jerk kids followed this move; Drakeo did not. Instead, he was toying with a style he would eventually dub “nervous music.” His mixtape of that name, released in early 2013, is not music to dance to — it’s better suited for driving on surface streets after dark, eyes fixed on the rearview mirror. While L.A.’s major-label artists were vaulting back onto the pop charts (YG was joined by artists like Tyga, who churned out digestible ratchet music, and the reliably antiseptic Kid Ink), Drakeo sunk into stranger, druggier sounds, gradually bleeding the animation out of his delivery and the fat out of his writing.

Over the next several years, Drakeo further refined this style, his voice growing lower. Meanwhile, the slang he and his friends had kicked around the schoolyard replaced, bit by bit, the stock phrasing young rappers across the country default to. His introduction to many listeners came in the spring of 2015, when Mustard remixed his song “Mr. Get Dough.” It raised his profile but would be Drakeo’s only significant contact with the majors system for years; Mustard hosted Drakeo’s next mixtape, but the rapper balked when the producer tried to formalize the arrangement and lock him into a contract. In any event, that record, I Am Mr. Mosely, can be seen as the beginning of his canonical releases. By the end of 2016, Drakeo followed that tape with I Am Mr. Mosely 2 and So Cold I Do Em; the latter includes a scathing diss of RJ, the Mustard–YG affiliate who had been grafted onto “Mr. Get Dough.”

So Cold and the second Mosely find Drakeo’s approach fully realized. Where “mumble rap” became a pejorative used to deride melody-driven rappers out of Atlanta, the term could more appropriately apply to Drakeo, who wrote and delivered lines as if they’re private jokes whispered to a friend or a running monologue muttered to himself. There is a contradiction at the heart of this style that makes it durable and consistently surprising: While the syntax suggests many lines are afterthoughts, and while verses and runs within verses often begin on strange parts of the beat, they inevitably reveal the sophisticated architecture holding his songs together. Passages that seem at first to be completely unmoored from a song’s rhythm track eventually lock into previously unseen pockets, recasting the beat as source code for the rapper to rewrite as he sees fit.

These tapes made Drakeo a rising star in L.A.’s underground and turned his friends, who were now calling themselves the Stinc Team, into one of the city’s most interesting rap collectives. (Second in command was his younger brother, Devante, who had rechristened himself Ralfy the Plug.) But that momentum would soon be interrupted. In January 2017, the sheriff’s department raided Drakeo’s apartment on Aviation Boulevard, near LAX. They arrested Drakeo along with several family members and friends, including Ralfy. Detectives also seized guns, which they were hoping to tie to an unsolved 2016 murder in Carson. Drakeo spent almost all of 2017 behind bars on gun and gang charges. (At this time, he had not been charged in connection to the Carson shooting.) On the outside, his music was gaining more and more traction; inside MCJ, he was dogged by neighborhood rivals and wired informants trying to elicit confessions.

He was released in November 2017 and practically moved into the studio; in just ten days, he would record Cold Devil, the album — largely written in MCJ — that stands as not just his masterpiece but the defining record for this era of L.A. street rap. As a vocalist, he was deepening the grooves that Mosely 2 and So Cold first wore in. He could be more guttural than ever before but also airier, more weightless; his voice could be wispy in the micro but muscular when taken in the whole, as if only the silhouette of normal speech remained. Cold Devil is also the album that introduced an even wider audience to the slang Drakeo so slyly deployed and expanded throughout his career: Guns with extended clips naturally became Pippi Longstockings, and home invasions —a Stinc Team specialty — became “flu-flamming.”

While his music often hinges on menace, phraseology like that lets slip the playfulness that underlines so many Drakeo songs. He was not only inventing terminology but pulling equally strange turns of phrase from ’50s game shows and ’90s childrens’ books; after MF DOOM, he is the rapper most likely to punctuate a verse with “Zoinks!” Cold Devil synthesized this unlikely raw material — the disparate bits of obscure vocabulary, the cryptic recollections of crimes petty and unspeakable, the sound of the crumpling hundred-dollar bills he sometimes stood on while he recorded — into an enthralling mission statement.

As Drakeo suspected, though, his freedom was fleeting. In March 2018, after just five months on the outside, he was again arrested, this time charged with special circumstances first-degree murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy to commit murder. All charges stemmed from that 2016 shooting in Carson, which left one man dead and two injured. The deceased was Davion Gregory, better known in some parts of L.A. as Red Bull, a prominent member of the Inglewood Family Bloods. Surreptitious jailhouse recordings suggested that the shooter was 17-year-old Jaidan Boyd, a Rollin 40s Crip. Another recording hears a snitch trying and failing to get Boyd — who incriminates himself during the conversation — to pin the shooting on Drakeo; Boyd does not, saying only that he was relieved when people noted online that Drakeo’s recognizable Mercedes was in the parking lot where the shooting occurred. Boyd implicates just himself and Mikell Buchanan, another Crip known as Kellz.

Despite this information, which they went to great pains to secure, the state — led by LASD detective Francis Hardiman — was evidently desperate to pin the killing on Drakeo. Afer Drakeo’s release in 2017, Hardiman seemed to become fixated on the rapper, who taunted the police on record and in his videos. Hardiman argued that Gregory’s murder was actually the consequence of a plot by Drakeo to stake out and murder RJ, whom he had observed Drakeo bickering with online. This convoluted theory — which ignores the much simpler Rollin 40s–Families beef, and which RJ himself rejects out of hand — would keep Drakeo locked up for more than two and a half years and force him to stare first the death penalty, and then life imprisonment two different times.

Over the summer of 2019, Drakeo stood trial at the Compton courthouse alongside his two co-defendants, Kellz and Ralfy. The inclusion of his brother, who was essentially accused of buying luxury fashion goods with stolen credit cards and sharing those belts and shirts with his friends, served chiefly to bolster the prosecution’s argument that the Stinc Team is a gang. Because this is California, that classification would open up the possibility of sentencing enhancements on any possible convictions. Of course, the suggestion was ridiculous; more than once, Ralfy, Drakeo, and much of the gallery were left laughing at the prosecutors’ attempts to cast the Stincs as a mafia-style operation. (During closing arguments, one of Ralfy’s attorneys argued that, under the state’s intentionally broad definition of a “gang,” the sheriff’s department itself was the clearest example of one; the judge, furious, cleared the courtroom.)

At the end of the trial, Kellz was convicted of murder and numerous attempts, and Ralfy was found guilty on some but not all of his comparatively minor charges. Drakeo was acquitted on nearly all of his counts, but the jury was hung on two: one of criminal gang conspiracy and one of shooting from a motor vehicle. The district attorney chose to refile those charges, a decision that, it soon became clear, would keep Drakeo locked up for at least another year beyond the 16 months he had served to that point.

Throughout that first trial, prosecutors tried to make the case that Drakeo’s music revealed him to be a ruthless killer. To anyone who has so much as a passing knowledge of rap’s relationship to the justice system, the state’s strategies will be familiar: hyperliteral readings of lines that are knowing genre tropes, obvious exaggerations, or simply fiction. A broader refusal to acknowledge Black artists’ creative agency dovetails perfectly with a desire to incarcerate men like Drakeo; an idle gun in his verses is damning the way a brutal killing in a white director’s movie could never be. Despite the consequences, Drakeo embraced this, gleefully baiting his fans in the sheriff’s office and rapping often about the way his identity was skewed by their slandering of him. Take “Ion Rap Beef,” a collaboration with the still-incarcerated 03 Greedo, where Drakeo drily raps, “Judging by my case files, I’m obsessed with rifles.” (Even after his release, he would dot his records with news anchors fretting about robberies in expensive zip codes.) Drakeo loved to rap with equal venom about murder and lifting shirts from high-end retailers; the conflation of the two was the point.

This sort of rhetorical judo is best seen on 2020’s Thank You For GTL, the album Drakeo recorded over the phone from MCJ while awaiting his retrial. GTL is a marvel of sound design — the woozy beats are handled entirely by the producer Joog SZN, and the cell-phone recordings are somehow rendered cleanly by the engineer Navin Upamaka — but also one of the most startling provocations of the justice system that rap has ever produced. It culminates with a song called “Fictional,” which explicates the eternal argument against the policing of rap music and is dotted with intrusive messages from GTL, the telecommunications company that gouges prisoners and their families for short phone calls, which Joog and Drakeo brilliantly repurpose as DJ drops. The album is also revealing of Drakeo’s process: His vocal takes are naturally left more naked than ever before and show that the little laughs and muttered asides that color his music are not pasted on after the fact but rather natural parts of his delivery. GTL is also improbably sort of joyful; it is heartwarming to hear him say, before certain verses, that he’s had this one in particular memorized for some time now.

In November 2020, just after Election Day, the state offered Drakeo a plea deal: Cop to shooting from a motor vehicle and walk with time served. The day Drakeo pleaded out, he immediately went to a recording studio just east of Hollywood. Here, he reunited with dozens of friends; with longtime collaborators like Joog and Upamaka; with glittering jewelry in place of the chains that shackled him on the way to and from court every day. He did not luxuriate in this. GTL had barely dented the reams of writing he produced while inside — when he left MCJ, he brought with him a garbage bag full of loose-leaf paper. He must have recorded a half-dozen songs that first night, consulting these pages and his iPhone Notes app like a mad scientist piecing together a half-remembered formula.

One of the songs Drakeo cut that night was “Fights Don’t Matter,” a perfect little microcosm of his outré humor and syntactical mismatching. In it, he cuts his hair like Boosie and kicks his enemies like Jet Li; he pinpoints, somewhat ruefully, a moment from his past as being back in his “Gucci days.” When a plug quotes him a price he appreciates, Drakeo starts Paisa dancing, and when he stops the song dead in its third verse, it’s to admit that he’s “a showboater.” Even the naked threats (“I’mma leave him dead in the street with his iPhone 7,” “I just beat a n- - - - with a Neiman Marcus store bag”) are delicious in their specificity. The video for “Fights” accentuates the unreal elements of Drakeo’s writing, making his chains pop out like the eyes of a cartoon wolf who spots a leg of lamb. He lets the editing do the work on that front, trusting as always that his wit would cut through the deadpan he affected.

“Fights Don’t Matter” was included on We Know the Truth, the comeback mixtape that gave way to two more in a Truth trilogy, then a collaboration tape with Ralfy, and finally a sequel to So Cold I Do Em. Over the final year of his life, Drakeo released more than five and a half hours of music, virtually all of it essential: He is the rare artist for whom sheer volume has a clarifying rather than dulling effect, underscoring his shrewd use of repetition, his tonal adaptability, his love for the little language games that sustain some songs on their own. These are not data dumps; each record has its own shape in terms of musical momentum and cockily pulp narrative arcs. But each is enhanced by immersion. When you try to map the contours of his thinking — get closer to it, make it more predictable — it eludes you over and over, an expensively loafered step ahead.

The five records Drakeo released over the past 12 months were generally well-received if understudied. He was never going to be a pop star, but his new LPs were widely covered in the press, his streaming numbers appear impressive, and he was greeted warmly by many major artists, especially those from outside L.A.; Drake gifted him a song, “Talk to Me,” for February’s The Truth Hurts. His first hometown show since the trial, a September gig at the Novo downtown, was triumphant: packed, raucous, and safe. Not everything on the outside went so smoothly. In February, one of his best friends, the Stinc Team rapper Ketchy the Great, was killed in a car accident in Long Beach. Over the summer, he was arrested on a gun charge after the LAPD waited for him to get into an Uber with his young son then pulled over that car, supposedly for its window tint. He had a court date scheduled for today.

Drakeo’s death — like Ketchy’s — comes during a period of unfathomable loss in hip-hop. The past five years alone have seen the murders of Bankroll Fresh and King Von in Atlanta; Jimmy Wopo in Pittsburgh; 3-2 in Houston; FBG Duck in Chicago; XXXTentacion in Miami; Gee Money in Baton Rouge; Huey in St. Louis; Nipsey Hussle, Mac P Dawg, and Pop Smoke in L.A.; Chinx Drugz in New York; 18veno in South Carolina; Bris in Sacramento; MO3 in Dallas; Willie Bo at the hands of police in Vallejo; Young Greatness in New Orleans; Nina Ross da Boss in Tampa; Young Dolph in Memphis; and, earlier this month, Slim 400, also in L.A. (Of these men and women, only 3-2 reached the age of 40.) This is to say nothing of those rappers who have died following drug overdoses, like Fredo Santana, Shock G, DMX, Juice WRLD, and Mac Miller, or those elder artists who have recently succumbed to myriad health problems, like Biz Markie, Black Rob, Gift of Gab, Prince Markie Dee, and Kangol Kid. Each of these lists is incomplete.

It is often said that this torrent of deaths has a numbing effect. That might be true when they are taken in the aggregate, converted into 1’s and 0’s and turned routine. Drakeo’s death is an incalculable loss for hip-hop and for L.A.’s broader culture, but it will also tear through his immediate community. He leaves behind a son, Caiden, who is about to turn 4. His mother, Darrylene, vows to sue Live Nation; a layperson imagines the case would be strong, though few families could be more intimately familiar with the court system’s failings. What can be said for certain is that Drakeo the Ruler will stand as one of the most significant artists of his generation, a self-made millionaire who did not bend an inch toward the record industry’s preferences or the threats of his enemies. He was a lyrical genius who emptied his notebooks and his psyche onto records, whose most inscrutable tics were studied and metabolized by people who would never meet him. His imprint will be traceable forever.