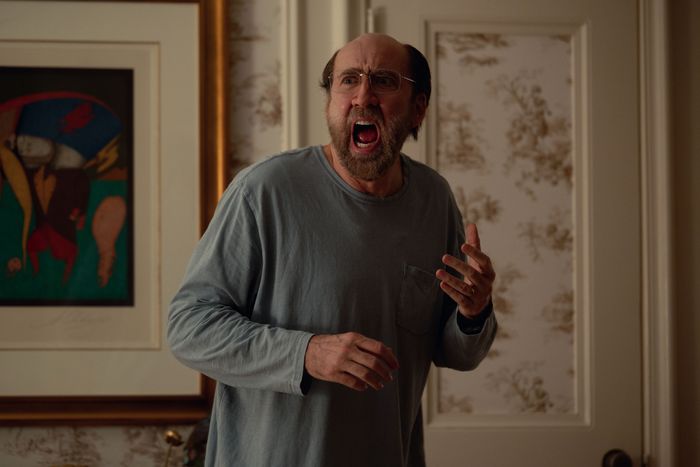

No filmmaker has probed viral fame and the ways internet culture is invading our collective condition quite as effectively as Kristoffer Borgli. After making the 2017 marketing-industry satire Drib, Borgli’s major breakthrough came earlier this year with Sick of Myself, a caustic comedy about a millennial (Kristine Kujath Thorp) who gives herself a ghastly skin rash for attention. His newest film, Dream Scenario (out November 10), follows an anxious, stagnant biology professor named Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage) who becomes an overnight celebrity, literally, when he starts showing up in people’s dreams for no clear reason. Stardom has untold consequences as Paul’s life spirals beyond his control, subject to strangers’ increasingly misguided projections.

Borgli doesn’t plan to satirize the customs of the extremely online forever — he says the script he’s writing now is about “love and how far we’re able to go to forgive someone” — but his timely worldview makes him one of 2023’s indie darlings. The 38-year-old Norwegian director has been traveling the festival circuit with Dream Scenario, building momentum for an A24 film that could be an Oscar vehicle for Cage, who hasn’t been nominated since 2002’s Adaptation. I had coffee with Borgli in late September at Fantastic Fest. We discussed what fueled these two movies that might leave you wanting to log off forever. (Mild Dream Scenario spoilers follow.)

Looking at Sick of Myself and Dream Scenario together, is it fair to say you are skeptical of the idea of viral fame?

I guess I’m aware of the costs of engagement. I’ve been just seeing and observing our culture and collective behavior, and it is a very new type of interaction that we have with each other. We are more physically disconnected, and we have a more parasocial relationship with each other. We all connect through our personas, and our personas can start taking on a life of their own — and you have no control over that. Those things seem kind of scary.

You said Sick of Myself started with an image of a privileged blonde woman in Oslo. What was the image that kicked off Dream Scenario?

The dying scream of an antiquated man.

All right, go on.

It just felt like this, like, ghost of a man that used to be okay. Paul Matthews is confused about his place in the world, and I think he feels cheated out of academic recognition. He has an old way of thinking about status, and then he gets thrown into a phenomenon where he conflates the idea of a desirable status with the very contemporary mass-viral fame that anyone can stumble upon.

Was his viral fame the hook of the movie for you, or was it built out of what might happen to this middle-age guy who has lost himself and is ambling around?

What was interesting to me was the preconceived notion of someone, the misconstrued image of someone, the idea of persona and person not matching up. I think the very first scene I wrote after having thought of this concept was the very strange sex scene in the middle of the movie. A persona has traveled around the world and manifested itself in the heads of others, and the mismatch between the idea of them and the reality leads to a crushingly cringeworthy disappointment. It’s the comedy of expecting something and getting something different, like that meme “What I ordered vs. what I got.”

Sick of Myself is a movie about somebody who will go to extremes to achieve recognition. Dream Scenario is about somebody who has recognition thrust on him and then extreme things come out of it. It could be read as a response or a companion piece to Sick of Myself. How do you position the two movies together?

Well, I was still writing drafts of Sick of Myself when I started writing Dream Scenario, and then suddenly I had scenes and ideas that could go in either. They’re definitely both from the perspective of a society where most of our basic needs are taken care of. What is left is self-actualization and a desire for recognition — these more abstract and existential problems that don’t have one specific solution, and how we do kind of strange things to try to quench that desire. We make ourselves miserable in the absence of having that desire met. It’s like your happiness is held hostage to an unattainable goal. You’re driven by that, and you forget to stop and smell the roses.

Maybe more so in Dream Scenario, it’s about the lack of perspective. You start out with someone who has a pretty good life, but his perspective is so wrong. He’s looking at the negative spaces: What’s missing from my picture? By the end of it, all he wants is to have what he once had. With Sick of Myself, it was more about figuring out a way to cinematically manifest a kind of cultural disease. The sickness became a way to photograph something that’s very much on everyone’s minds. In both of these movies, there’s a lack of showing screens or social media, but everyone speaks about social media.

Which is interesting because most movies about social media try to find a way to depict it.

Yeah, and in these movies, no one is talking about “I’m doing this for the clout.” I don’t think it’s clear in Sick of Myself if she has a social-media presence that much, but I think people draw those conclusions because we are all living in this current age. Wanting recognition or status or sympathy or love or whatever is a timeless idea, but it’s hyperpropelled by all of these new opportunities. We’re just living in a world where we have massive amounts of empty-calorie versions of success, and more and more they are replacing noble ideas of ambition. There are all these shortcuts to feeling successful, and you can live in a bubble where you have a phenomenological experience of being successful, even if it’s untrue.

And almost inevitably, you become addicted to the feeling of that success and its gratification. It can be brain-altering. Something I think the second half of Dream Scenario captures really well is the life cycle of a viral star. First Paul is beloved, and everybody wants a piece of him. Then there’s a backlash and he loses his job. Then there’s an apology, and the apology is adjudicated and rejected. Then some sort of branding opportunity pops up where someone turns his experience into a capitalistic pursuit.

You forgot one: the contrarian industrial complex opening their doors once he’s rejected from the mainstream.

You mean how he becomes an alt-right icon after the backlash? He finds an audience that projects what they want to see onto him.

Yeah. And each version is, How to monetize and capture him in this very abstract phenomenon? It’s reducing it to something very simplified or banal. That’s something that happens a lot in our culture. Even this movie could be naïvely reduced to one sentence, like, It’s about this or that. I’ve already seen some reviews doing that. It’s the bite-size reduction of everything in our culture.

When you were thinking about the plot, did you graph the second half of the movie according to that viral life cycle we’re talking about?

I had the sense that there was a playbook. I applied the playbook. It’s Save the Cat!, the book for writing stories, or Robert McKee’s Story. And then there’s the cultural playbook. Let’s throw both together and see what happens.

Correct me if I’m wrong: At one point, was Ari Aster going to direct this with Adam Sandler?

No. I saw that as a trivia item on IMDb. I don’t know how that rumor emerged. It was always me directing, but it is true that Adam Sandler was attached.

What shifted?

I wrote this movie going into the pandemic. It was set up at A24 in May 2020.

Oh, so before Sick of Myself.

Yeah, and Sick of Myself was set up around the same time. My schedule was very abstract: How do we shoot a movie now? Should I do that one first and then this one? And then Adam Sandler’s calendar got even more complicated. By circumstance, we just couldn’t find the perfect timing. So it ended up being Nicolas Cage, and now I can’t unsee that.

You need your protagonist to be able to cut through his neurosis and appreciate the viral fame. I don’t know if Adam Sandler can cut through the neurosis the same way, if that makes sense.

I think what’s unique about Nicolas Cage is that his persona has outgrown the man. It’s almost like he’s a mythical creature. Adding that into the equation of this movie was just hugely interesting.

I don’t think of Nicolas Cage as someone who’s extremely online and in touch with the arc of virality. What conversations did you have about that?

His first response was, “I have been through this.” He understood the bigger philosophy of the movie and the feeling that your persona runs its own course.

I suppose any celebrity can relate to that.

Yeah, but him especially. It feels like Nicolas Cage has become a symbol almost, a Jungian idea. I think he’s sort of in a unique position in that way.

Cage has been celebrated for the gonzo performances he’s been doing lately, like Mandy. This one feels a bit more like Adaptation.

I didn’t want the meta layer of one of the most famous people on the planet playing a random nobody. I felt like I needed to hide him a little bit. He needed to become Paul Matthews, not only visually with the hair and the makeup and the costumes but also in his mannerisms. We discussed that. Nic Cage has so much natural charisma and energy. He is an alpha. Paul is a beta. How do you shave that off and come down to his level? That was really interesting, to find the suburban dad inside of Nicolas Cage — but also seeing how his energy came bubbling through the surface in certain moments. His energy comes through in these little tics. The first half of the movie, he’s staying in this beta shell. He’s wearing his jacket like a protective blanket. It made that part of the movie even more watchable. And then once he starts enjoying his new status as a somebody, the real Nic Cage energy started coming more to life. It was really helpful because I hadn’t thought of the energy that comes to life in those moments, like when all of his students are recounting their dreams. He’s so enthusiastic in that scene. That’s something he brought. I love the way he chose to do that. It made the character more complex. It became more apparent that he’s having an identity crisis.

Right, because that’s the moment when you see how seductive this type of recognition is and why people find it so aspirational. Did you ever consider including more of the sci-fi element? It risks getting into Inception territory, but do you have a sense of why this is happening to Paul?

I started thinking, Should the movie explain it? Every time I was thinking about it, I got kind of bored. I’m not very interested in plot. Plot is a necessary evil. I want to look at a character, especially in scenes where the crisis is a bit heightened and it reveals something. This plot is a great excuse to drag a person through this roller coaster of ups and downs, but it was more fun to keep it a mystery and let the movie have a touch of the unknown. It has some dream logic to it. I want people to debate, “How much, exactly, is a dream? And are movies dreams?” A dream is supposedly the length of a movie-ish, and when we’re in the theater we are collectively sharing a dream. Can you trust the movie? The movie itself is kind of like an unreliable narrator.

Is Nic wearing some kind of bald cap?

No, he shaved his head. It was an idea that Nic had but started regretting right before having to commit to it. But once he had pitched it, I started falling in love with it.

For better or worse, part of every director’s job is to promote their work. You’re online, you have an Instagram. There are a couple of comedy videos on your grid. And you’re also critiquing self-promotion and fame in your movies. How do you decide what kind of profile you want as someone who is becoming a public figure?

From my perspective, if there’s a message in the movie, it’s almost like, “Please enjoy not being famous. Enjoy your anonymity. It’s priceless. It’s a good thing.” And then, of course, the irony of making a movie like this is the cost of getting dragged into some of that. I have actors who can deflect some of it and take a lot of it off of me.

You’re not Nic Cage, that’s true.

Exactly. He will suffer more of this, and that’s completely fine with me. Yeah, it’s a little bit intimidating, the idea of entering the collective psyche. Of course it is. I want to potentially live in some people’s heads but not everyone’s.

If you keep making movies on the scale of Sick of Myself and Dream Scenario, you’re going to have your place in the culture, but you’re not Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese or Sofia Coppola — someone who’s recognizable by face alone.

Not yet!

Well, that’s what I’m saying. If you want to scale up and work with bigger studios and stars, you might become a recognizable face. Obviously, you don’t need to be prescriptive about it right now, but is there a line you want to draw for yourself?

I feel like as long as I get to live in the public psyche, as we said, through my ideas more than as a person, then I’m completely fine. That way, I’m in control. When I put a movie out there, it’s deliberate. I’ve thought about it. I want it to live out there. So if it can stay that way, where I have my own privacy and then I can tap into the public collective consciousness with deliberate pieces of art and we can debate the art, that’s completely fine. I hope that’s achievable.

What I think you’re saying is there can be value in fame and that type of success when there’s artistic merit or when there’s some sort of contribution to the world, as opposed to somebody who’s chasing this digital, influencer-y clout.

Yeah. It’s in my lifetime that fame stopped being a by-product of something else and started becoming a product.

When we were growing up, you had to make a record or a movie or write a book to become famous, for the most part. Now you can be recognizable for doing none of those things. I guess the great philosophical question of our era is, “Is there any value in that?”

I think it’s the fast food of creativity. It’s not even creativity. There’s no nutrition in just recognition. If the recognition is from something we can appreciate that has value, those are nutritional calories. I think we haven’t yet grasped how unhealthy this fast fame is.

Do you think this is a preoccupation that will continue to sustain you artistically? You’ve now made three movies that have something to do with viral fame, branding, and capitalism all swirling together. It would be easy to paint you with one brush and say, “Here’s the satirist of viral life.”

I think I’ve sort of exorcized some demons. I started in my 20s working in marketing. I was hired to do commercials. I saw inside the sausage factory, and I also lived in a world where we were mostly preoccupied with the higher levels on the hierarchy of needs — you know, self-actualization. Those were just themes that were really pressing for me. I think those ideas chose me. They’ve been ruminating in my head for a while. With these movies, I kind of feel like I’ve had my final word. For me, it’s important to respond to the moment that we’re living in. I feel like I’m always in a constant debate with the world as I’m navigating it. These movies are as much a tool for me to figure some things out.