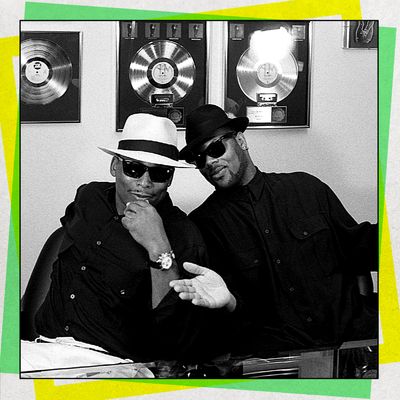

Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis changed the face of R&B, working early on in the Minneapolis-based band Flyte Tyme, which morphed into the funk outfit Time at Prince’s urging, and later as songwriters and producers for a who’s who of Black music royalty. Jam and Lewis penned hits for Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, New Edition, Alexander O’Neal, Boyz II Men, and more. Comb through the credits of any classic R&B album of the ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s, and they’re most likely in the mix. They worked on Heart Break (“If It Isn’t Love, “Can You Stand the Rain,” “You’re Not My Kind of Girl”); they worked on The Velvet Rope (“Got Til It’s Gone,” “Together Again”); they worked on Confessions (“Bad Girl,” “That’s What It’s Made For”). They were nominated 11 times for the Grammy for Producer of the Year, Non-Classical over three different decades, the most of any musical act in Grammy history. It is a crime that they only won once.

This week, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis release Jam & Lewis Vol. 1, their first album as artists. It’s a testament to their gifts as writers of wrenching love songs and as producers capable of juggling soulful sonics and crisp hip-hop drums. The guest list — Mariah, Mary J. Blige, Toni Braxton, Charlie Wilson, the Roots, Babyface, Morris Day and Jerome, Usher, and more — speaks to a lifetime of excellence in R&B. It’s also an undertaking first hatched 35 years ago when work wrapped on Janet’s blockbuster Control album. To hear the guys tell it, they’d always intended to do an album, but songs kept getting swiped by said murderer’s row of collaborators. Below, you’ll find a few stories about their friends and the history of a genre.

Biggest reason it took 35 years to release your own album

Jimmy Jam: We were going to do an album when we were working on Janet’s Control. John McClain was the A&R at A&M Records, [Janet’s label at the time]. He came up to Minneapolis, and we played what we had for Janet. We had “Control,” “Nasty,” “When I Think of You,” “Funny How Time Flies,” “Pleasure Principle,” and “Let’s Wait Awhile.” All of those songs were done. We said, “We’re good, right?” John, as all A&R people would do back in the day, said, “I just need one more.” What are you talking about, one more? So we go to grab a bite to eat, and Terry puts a cassette in. “John, listen to this. This is our stuff from our album.” It was just tracks. The third track came on, and he loved it. He was like, “This is the one I need for Janet.” We’re like, “What are you talking about, man? That’s for our album.” He said, “No, no, no. I need this for Janet. Play it for her and, if she likes it, give it to her.” John was very convincing.

The next day, we went to the studio and put the track on. We didn’t tell them we were putting it on. We just watched her. We could always tell when Janet liked a song by just her body movements, her facial expression, the whole thing. She’s putting her head down. She’s grooving to it. She comes to the door and gets … We always call it “the ugly face.” When something is really funky, she gets the ugly face and she points at us. When the song goes off, she goes, “Who’s that for?” We said, “You, if you want it.” She wanted it. That song became “What Have You Done For Me Lately.” Her album was already done, but that became the first single, as John wished. It started her career and ended ours, or at least our album at that point. The song on Control just after “What Have You Done For Me Lately” called “You Can Be Mine” was also for our album. Really, she took two songs from our album.

Over the years, we kept trying to make another record, but people kept taking the songs for themselves. We finally got selfish around the time we were inducted in the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame [in 2017]. We went in and finally said, “We’re going to start keeping songs for ourselves.” T [Lewis] was the thing that finally put us on the track to do it. We put a wishlist together, and Babyface was one of the people on the top of it. We started doing that record and just continued on and that was how it all came together.

Favorite song by the Time

JJ: It’s a different answer on different days, but we were up really early doing CBS This Morning, and they played “Get It Up.” I’ve got to tell you, “Get It Up” is my favorite Time song right now, very simply because it was the first song, because of the experience of hearing yourselves on the radio for the first time. We’d been in L.A., driving down Hollywood Boulevard or whatever. The ladies of the evening were out. We were in a station wagon, and we heard our song on the radio, and we pulled over. These girls came up to the car saying, “Who y’all?” “We’re the Time.” “What do you guys sing?” We said, “Get It Up.” “Oh, we hear that all the time.” We were like, “Great!”

When we went to Detroit for the first time, there was this DJ, the Electrifying Mojo. We went to the station, and he played “Get It Up” 12 times in a row. He kept saying to the people, “”Who’s this? Who do you think it is?” After the sixth or seventh time playing it, he said, “They’re down at the station right now if you want to see.” We didn’t really think anything of it. After the 12th time he played the song, he said, “Watch this,” and he opened the curtain to the big window at the station, and there were maybe a thousand people out there all trying to see who we were. I remember people going, “Wait, is that Prince?” “No, that’s Prince’s cousin.” All the rumors started and it was crazy, but it was all because of “Get It Up.” So it’s the pivotal song, I guess.

Fondest Prince memory

Terry Lewis: There were a lot of days like this, but he used to come to our rehearsals every day and kind of watch and advise and suggest things that he would want us to do. Then, he would leave and go home and practice with his band, the Revolution, then go out to the club for a while. Every day, he’d come back with a different song. I remember the day he came back with “1999” because we had just come off a tour, and every day in every hotel that we were in, we would see this documentary about Nostradamus. When I heard [“1999”], it dawned on me: He’s been checking this documentary out. He just created a song based on what he learned about Nostradamus, how everything [was predicted to] be gone in the year 2000; everything was just going to implode at that point. That really changed the way I looked at a lot of things, especially in songwriting. [Prince taught me] to study and learn about what’s going on around you and how you can implement it into a pop song. That changed my take on what he did. He was so much more than anyone ever could conceive and know, along with being brilliant, like he thought he was.

JJ: When Prince walked into our rehearsals, he didn’t walk in all excited, like, “Wow, listen to this!” He’d walk in with a cassette in his hand, like [deadpans], “I did this last night.” He popped it in, and I was like, “What the fuck!?” Mind blowing. Then he just jumps into our rehearsal. Like, dude, are you kidding me?

TL: A lot of times, he’d do stuff that would just be over your head. I remember we had the argument—

JJ: About “When Doves Cry”?

TL: Yeah, “When Doves Cry.” We said, “You can’t do a song without bass.” He said, “I just did.” “It needs the bass.” “No, it doesn’t.” We argued about it. At least I did, because I’m a bass player.

JJ: Mark [Brown] told him the same thing.

TL: Boy, did he prove us wrong.

Best memory of recording with Michael Jackson

We were working on “Scream” in a New York studio [The Hit Factory], and he walked in basically breaking all of the studio rules, meaning that he was wearing jangly clothes and hard shoes. In a studio, the microphone picks up everything, so you don’t want to wear anything that’s going to make extra noise. He walks into the studio all calm and quiet, and he puts the headphones on and he goes, “You guys ready?” Janet was sitting with us. She said, “I’ll do my vocal. After Mike gets done, I’ll do the vocal.” So the song starts, and Michael turns into the Tasmanian Devil. He’s dancing around. He’s snapping his fingers, clapping his hands. He’s making all the noise, all the Michael Jackson noises. We’re blown away. We’re sitting there like little girls. He sings the song from start to finish. Then, he goes back to calm Michael and asks us, “How was that?” We’re speechless. We’re like, “Uh, yeah, yeah, Mike.” “You want me to try it again?” We go, “Yeah, yeah. Try it again. Yeah, yeah. That’s cool.”

As we’re saying that, Janet leans into us and goes, “I’ll do my vocal in Minneapolis.” She wanted no part of following Michael. The epilogue to the story is that after we finished Michael’s vocal — he did maybe three, four, or five takes, and we were done. We go to Minneapolis to do Janet’s vocal, and we send it to Michael, and he goes, “Wow, Janet’s vocal sounds really good.” We said, “Thanks.” He said, “Where’d she do it?” “Minneapolis.” He said, “Really? Okay, I want to come to Minneapolis.” So he was competitive, even with his sister. He wanted to make sure his vocal was on par with her. He came to Minneapolis, and we ended up using maybe 10 percent of what he did there. He’d nailed it in New York, but he showed us that competitive nature that he had. He loved Janet, obviously, but he heard her vocal, and it made him say, “I’ve got to get my vocal better now.” That was the most impactful studio moment we probably ever had.

Favorite song you produced for Janet Jackson

JJ: I’m going with “That’s the Way Love Goes.” There’s a million songs. I say that song simply because sometimes, in your mind, you kind of hear things. When we did the track, I thought about James Brown, because that’s my favorite shit, but I wanted to put melody and chords over the top of him because that sample had been used. “Papa Don’t Take No Mess” had been used a lot, by [Biz Markie’s] “Vapors” and by Snoop and a whole bunch of different people. I just thought, Man, if we could make a song out of that, that would be so funky, but it would also be cool. You could dance to it or just groove and listen to it.

The way the song happened was great. Janet didn’t like it when she heard it, initially. She thought, Eh, it’s okay. It wasn’t until she went on vacation with all her dancers and everybody… If you watch the video for “That’s the Way Love Goes,” where she won’t play the song for everybody, that’s kind of the way it happened. She was [on vacation] playing songs from the album, and that song came on, just the track, and all the dancers went, “Oh, my God! This is the one.” So when she came back to town, she was like, “We’ve got to finish that song.” She was all excited about it. We’re like, “The song you didn’t like?” She said, “No, no, no. I love it, I love it,” and whatever. I love it because of the way it turned out. It was No. 1 for eight weeks. If we hadn’t put it on the cassette that she took on vacation with her, that song would’ve been lost in the dust somewhere.

Favorite song you produced for Usher

TL: Actually, I don’t know if we’ve achieved the pinnacle yet with him. His star is very bright. The more we learn, and the more he learns, is only going to make a more dangerous concoction.

JJ: My favorite might be on [our] new album: “Do It Yourself” is pretty much the pinnacle for right now. We like that one a lot. I will say there’s a song we did with him awhile back [in 2001], though, called “Can U Help Me,” that I think is probably, vocally, one of my favorite Usher vocals that we ever were involved with.

Fastest singer you worked with in the studio

JJ: Well, I’ll say two people. I think, as far as the quickest singer we ever had, it’s Patti Austin. But I’m going to just mention one other name who was really quick, because he was always motivated to get to the strip club, and that’s Bobby Brown. Bobby Brown could sing! When we were working on the [1996] Home Again album with New Edition, Bobby Brown would literally come in for ten minutes and be done. And he was so good! He would nail it. Now, getting him to the studio was another thing. It may take two or three days to get him to the studio, but once he got to the studio, he nailed it. Ten minutes, he’d be done. And he’d be going, “Do you need anything else?” And it’s like, “No, no. We’re good, dude. We got you.”

Bobby was really good, but Patti Austin probably was the most accomplished. When she came in, we had allotted three days for three songs [for Gettin’ Away with Murder]. We’d do a song a day. She came in on the first day, hadn’t even heard the songs, learned them, did all the vocals on the first song and then said, “What do you want to do next?” We sent the next song. She finished that one. Then we were like, “Let’s come back tomorrow and finish.” She worked faster than we could even write lyrics. Not only with the lead vocal, but all the background vocals, too. She was amazing. “The Heat of Heat,” which was actually a big hit for her, she did all of that in, I don’t know, two hours, maybe. Maybe not even that long. First take, start to finish. She would nail it and then say, “Oh, you want a harmony on that?” and do all the harmonies. We learned why she was the secret weapon in Quincy Jones’s arsenal. She did background on every one of the Quincy records.

TL: You can’t leave out Michael Jackson, to me. He’s a one- or two-take guy.

Best album you worked on with members of New Edition

JJ: I just want to say that we came up with the idea for Bel Biv Devoe. It was our idea. But I’d have to go with the [1988] Heart Break album; it was such a pivotal album, musically, sonically. A lot of child singers don’t make the transition. There has to be an album that makes the transition from boys to men, so to speak. We literally wrote a song called “Boys to Men” that addressed it, which became the name of Boyz II Men. The song that Boyz II Men sang to Michael Bivins when they auditioned for him was “Can You Stand the Rain,” which was the song from the Heart Break album. That album introduced Johnny Gill as a viable singer; people knew the name but hadn’t really put it all together until then. So it did that. “If It Isn’t Love” made the transition from the Bubble Gum New Edition. It was the bridge that took them to the New Edition we know now. Obviously, it was a successful album, and a successful tour came out of it. I think that that’s probably the body of work that encapsulates the best of New Edition.

Best new jack swing album

JJ: The king of new jack swing is Teddy Riley; he’s the one that took it to a whole new level. We’re on the architecture team. “Nasty” was maybe the foundation of it, possibly, but Teddy made it into a thing. He named it and marketed it, made whole albums of new jack swing. On our albums, we’d have “State of the World,” “The Knowledge,” “Rhythm Nation.” They had the new jack swing flavor to them that “Nasty” sort of started. As an album, I would say probably Rhythm Nation 1814 has the most influence. I mean, to me, it was just a type of music that we loved. We loved the idea of sampling the hip-hop drums, but then we were also working with Janet as an artist who was such a great dancer. So it really combined all of the things that we loved about the music at that time. But I don’t think that there’s ever an album that I would say we made that’s just a new jack swing album, whereas I would say the first Guy album is probably a true new jack swing album.

Singer you worked with who deserved to be bigger

JJ: The one that pops into my mind is Chanté Moore. I loved working with her. She’s an excellent vocalist, technically, top to bottom. Just amazing. We never really got to make the record we wanted to make with her. We knew in our minds what we thought her album should be, as a body of work, but we never really got a chance to do it. We’d do one song here and two songs there, but we never had a chance to have an influence over a whole album, which I think would’ve been fun to do.

TL: Deborah Cox would be the one that pops into my mind. She had plenty of success. I just think, for my money, she’s an extraordinary artist. She’s someone you want to create for. She has so much talent, but I don’t think she got her just due, though, being under, I guess … the Whitney Houston umbrella. There can only be one queen in the castle, and it was Whitney’s castle.

JJ: That’s very true. I always think of James Harden. When he played for the Oklahoma City Thunder, initially, he was the sixth man on that team. Then he went to the Houston Rockets and was the man. I always think about if Deborah Cox wasn’t on Arista under the Whitney umbrella and went to a different team — if she would’ve been the main one on a team rather than the sixth man in the Clive Davis Arista Records era, where you had Aretha [Franklin] and Dionne [Warwick], all these other great singers there. Deborah is definitely a championship singer, but she was just sixth man on that team, basically.

Favorite hip-hop producer

JJ: Too many, but I would say J Dilla is at the top of my list. DJ Premier is up there, too. The way Dilla cut samples up, man … There was just nobody like him. I remember I was at a radio station once, I don’t think Terry was with me, but I’d gone to do an interview, and [DJ, producer, and Stones Throw Records founder] Peanut Butter Wolf was there with Madlib after us. We talked real quick, just met each other and said hello. When I got back in the car, the station started playing records from the Champion Sound album Dilla did with Madlib. And I wanted to tell the driver, “Turn around and go back to the station. I’ve got to talk to these guys.” Dilla was just so innovative in what he did. Some people, they break the mold. Prince was like that. There won’t be another one like him. His influence will be still around, but there won’t be another one like him. That’s the way Dilla is to me.

Best of the younger R&B generation

JJ: Well, I think top of both of our lists is probably going to be H.E.R. We love H.E.R. She is amazing in every way. She’s what I call a generational artist, meaning that in any generation, at any time period, she would’ve been the top of the top, if it was the ’60s or the ’50s or the ’70s or the whatever. Listen, Prince is our gold standard. Think about H.E.R.’s last performance where she comes down from the rafters of the arena playing the drums, then hops on the guitar and kills a solo. We also had her on the Prince special that we music directed, where she came out with Gary Clark Jr. and ripped the guitar, but then sat down at the piano and played. She’s the kind of artist that Prince, in his day, would’ve invited to Paisley Park. I know Terry has another Prince-influenced artist that he would probably name.

TL: Yes. Always H.E.R., but Janelle Monáe, to me, is one of those artists… She reminds me so much of our mentor just in her performance skills that I think if she has the right rocket ship, she’s totally out of here on the music side. She’s totally successful as she is, but that one rocket ship is still available, I think.

Biggest thing keeping you from doing Verzuz

JJ: It’s been offered. The right circumstances haven’t happened yet. I just don’t believe, necessarily, that music should be weaponized. Back in the day, we were in the battle of the bands and did all that kind of stuff, but that was our own music. As artists, I think it’s a little different. As a writer and a producer, I don’t want to necessarily use music going against other people. You know what I’m saying? I don’t feel it’s fair.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From This Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music