This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One afternoon in January 2022, the parents of two freshmen at Beal City High School in central Michigan gathered in the principal’s office. They were there to discuss the texts: vicious, anonymous messages flooding the phones of their children, Ashley Licari and Owen McKenny, sometimes 30 a day. The messages would arrive at any hour, and no one knew who was sending them.

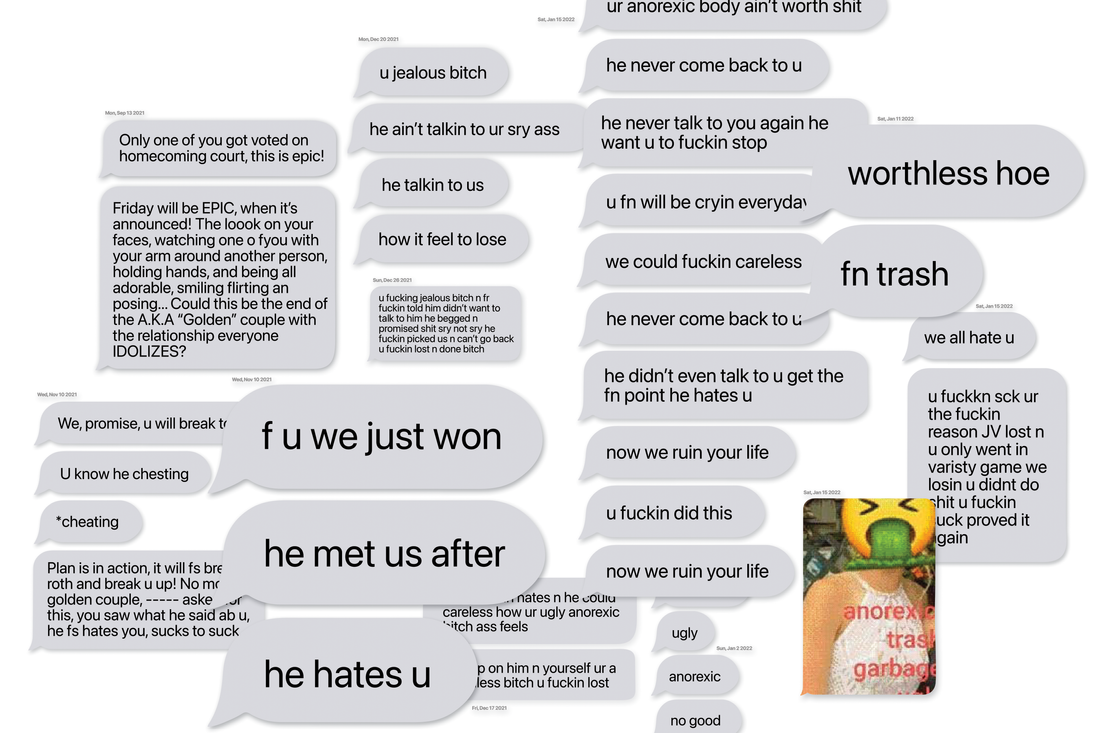

Although they were sent to both Ashley and Owen, they mostly targeted Ashley. The cyberbully seemed to know exactly how to pick at her insecurities. The texts mocked her thin frame, calling her an “anorexic toddler” with a “little tykes body,” and slammed her ability on the basketball court. Ashley and Owen dated in middle school but had broken up in the fall of freshman year, and the bully told Ashley that Owen was now trashing her behind her back and flirting with other girls. The bully described in detail the sexual moves they would do with him. One message included a homecoming photo of Ashley with a vomiting emoji pasted over her head and the words skank and hoe plastered in red on her body. In a group thread, the texter asked Owen to help take Ashley down and told her that Owen had “said his life would be better if you were dead” and “no one will care if u gone.”

At the meeting, Ashley’s mother, Kendra Licari, couldn’t stop crying. The superintendent and sheriff were there, too, but Owen’s mother, Jill McKenny, did much of the talking. She hoisted hundreds of pages of text transcripts from a Staples box and passed them around. The sheriff thumbed through the pages. Ashley sometimes texted back feistily, but at other points she would plead, “i honestly can not take anymore and will do anything you want if you will please stop.”

The texter seemed to know a lot about what Ashley and Owen were doing at school. They knew what shirt Ashley was wearing on any given day and how many basketball points she had scored (“LMFAO 2 points u suck”). The bully knew Owen had removed the phone case Ashley had given him as a gift, and they tracked his whereabouts in class: “owen sitting by me in history sry not sry we fuckin take u down bitch.” They constantly changed numbers using burner apps. But Kendra and Jill had homed in on a possible suspect: Khloe Wilson, a popular freshman athlete who had played sports with Ashley since grade school. The previous night, a potential slip-up — the bully gloated in a text about scoring 12 points in the basketball game. At the sheriff’s urging, Kendra, who often ran varsity’s scoreboard, left the room to fetch the prior night’s record. Only Khloe had scored 12 points.

At a preliminary meeting with the sheriff’s department many weeks prior, a detective had asked Jill if she feared that her son’s mental state was bad enough that he might harm himself. She had watched Owen withering — talking back at home, looking miserable, pulling from a reserve of anger on the basketball court that she didn’t recognize. But harm himself? Thankfully not. And what about Ashley? Kendra didn’t speak. Jill recalls answering for her: “The answer is ‘yes,’ Kendra. We are afraid Ashley could hurt herself.” Back in the principal’s office, the sheriff said he’d start investigating, and the parents left the campus with renewed hope.

Beal City, a farming community with two pubs and one flashing intersection, seemed like the last place on earth anyone could hide. The landscape is open and flat, broken into well-tended fields and dairies, wind turbines churning overheard. Many of its families boast roots that stretch back generations. It’s a place where, as one local said, “you want to be perceived as a good person.” When a parent is diagnosed with cancer, you start a meal train and sell T-shirts that say NOBODY FIGHTS ALONE. You volunteer to ladle cheese onto nachos at the stadium concessions to help the Sports Boosters and send your kid to practice with extra cleats for the boy who needs some. The heart of town is its prized public school: a single brown-brick complex, K-12, with just 50 students per grade, a foyer decked in sports-championship trophies, and a mural chirping CHARACTER COUNTS!

The parents wanted the cyberbully to be outed and expelled. Most important, they wanted their happy, carefree children back. No one could have imagined that the hunt would stretch on eight more exasperating months. Or that, on that January afternoon at Beal City High, the bully had been sitting in the room.

In the fall of seventh grade, Owen sent Ashley an Instagram DM. He had gotten his first cell phone only that year, one of the last kids in his grade without one. (“We’re those parents,” his mother said.) Ashley, a softball and basketball player in his class, was delicately slim, tomboyish in hoodies and jerseys, her blonde hair sometimes braided in an arch over her crown. “She stood out,” Owen remembered. “Pretty, athletic, super-kind.” With classic seventh-grade diplomacy, Owen had his friends tell Ashley that he liked her. After she came to his football game, “I texted her literally that day. I’m like, ‘So are we dating?’” Owen says. “She’s like, ‘I don’t know. Do you want to be?’ And I’m like, ‘Sure.’”

Owen’s parents, Dave and Jill McKenny, had also started dating in seventh grade. Dave had been a star outfielder at Beal City High — a fact that matters in a town that revolves around the school and its state-title-clinching Aggies — and Jill had been a Beal cheerleader. The McKennys were an established family in the area: While he coached kids’ baseball and worked as an IT manager at a farm lender, she was a super-volunteer at the Catholic elementary school. Kendra, on the other hand, grew up about a two-hour drive away in the exurbs of Detroit. While studying at Central Michigan University, she met Shawn Licari, a Beal City High alum, and eventually moved into his simple one-story house. Ashley, their only child, was born in 2007.

Locals concede that Beal City can be a tough place for transplants, that anyone who didn’t go to the school or doesn’t have one of the known last names will always be considered from “not around here.” And though Shawn was from Beal, he hadn’t been part of the in crowd, a friend of the family says. “So I think it was probably important for Kendra to make sure that Ashley was.” (The Licaris declined many interview requests; Ashley, a minor and a crime victim who didn’t participate in the article, has been given a pseudonym.) A former high-school basketball player, Kendra coached her daughter’s travel softball team in elementary school and, later, middle-school hoops. She splurged to join the spring-break caravan of Beal families that flocked south to rent condos on the Florida or Alabama coast.

While Ashley was on the quieter side, her friends knew Kendra as the outgoing “cool mom.” At school events, she would approach a gaggle of students to gossip. Through softball, Ashley had befriended Paige and Natalie Antcliff, fraternal twins three years older from a longtime Beal City family, and they’d film Kendra crossing her eyes, dancing to Sir Mix-a-Lot, cartwheeling down a hotel hallway on tournament weekends. To onlookers, it was clear that Ashley and Kendra were at the center of each other’s lives, but by junior high, people observed that Kendra would brag about her daughter to the point of annoying other parents. “Everything was ‘Ashley’s softball, Ashley’s school, Ashley’s this, Ashley’s that,’” says one.

After Ashley started dating Owen, her mother came along, too. At every opportunity, Kendra would ask them to wrap their arms around each other for a photo, which Ashley would turn into presents for Owen, like a personalized phone case. When they hung out at the Licaris’, Kendra would chime in: “Why don’t you jump on the trampoline? Take a spin in Ashley’s Ranger utility vehicle?” Kendra talked about the kids, Jill says, “like they were going to be together forever.” Once, Paige Antcliff saw Kendra take Ashley’s phone and read her daughter’s texts with Owen. Then, as Ashley, Kendra typed out a reply: “I love you.”

When COVID sent students home in the spring of seventh grade, the Licaris joined the McKennys’ pandemic bubble for dinners and bonfires. Owen was a talented Little League pitcher, and over the summer, the families traveled as a group on their children’s tournament weekends and camped together. In eighth grade, Kendra signed up to coach Owen’s track team, becoming, he says, “like a second mom.” A regular spectator at Owen’s matches, she drove Ashley three hours across Michigan to watch one of his championship games. Once, Kendra even suggested turning Owen’s tournament in Florida into a Licari family vacation, to which Jill had to gently say “no.”

Even so, the McKennys didn’t feel anything was amiss. “The family’s whole life was just watching Ashley play sports,” Jill says, and Owen seemed an extension of that. Dave saw Kendra’s intentions as harmlessly basic: She wanted to belong.

A few weeks after they started dating, the first anonymous texts hit Owen and Ashley’s phones. The jeering messages said that Ashley wasn’t invited to the annual Halloween party thrown by Khloe Wilson’s mother, Tami: a Beal City headliner event, complete with an elaborate haunted trail through her acreage. Owen showed the texts to his parents, who shrugged them off — it must be some kid who just wanted them to break up.

For a year, the texter remained silent. Then, in the fall of 2020, when they were in eighth grade, Owen and Ashley got more messages:

It is obvious he wants me, his attention is constantly on me … Not sure what he told you but he is coming to the Halloween party and we are both DTF.

He wants nothing to do with you … He think you’re annoying and an ugly ass bitch and wishes you would leave him the fuck alone … Why do you think he is on his phone all the time texting me? … You didn’t get invited to sleep with him, I did. I’m spending the night with him, I’m sharing a bed with him, not you.

The texts continued sporadically through the end of that year. Jill showed them to school officials, who said to block the number. (Tami Wilson caught wind of the incident and called Kendra to assure her that Ashley was certainly invited to the party.)

Sometimes, Ashley would fight back: “I don’t care what you say owen and i are solid and you’re not going to break us.” Other times, she’d take the bait. She’d text Owen: Was he hanging out with other girls? Did he want to break up? Owen would text or FaceTime back, smoothing things over.

But by the start of high school, Owen had begun to pull away from his girlfriend. The texts made up 75 percent of the reason, he calculates. “It’s just hard to be with someone after all that,” he says. At a volleyball match in August of their freshman year, Owen and Ashley sat apart from each other. That’s when Ashley started getting texts from her mother, across the gym:

Sit next to him

Answer me

Come here now

I’m pissed

Move your ass

Now

now

I am fuming pissed off

This is ficking ridiculous

Answer me and move your ass

Meanwhile, the anonymous bully was picking up the tempo. Some of the texts seemed to build Ashley and Owen up while also tearing them down. In September, in the lead-up to the homecoming dance, the bully claimed that only one of them would be voted onto homecoming court: “Could this be the end of the A.K.A “Golden” couple with the relationship everyone IDOLIZES?” On another day: “you’re the definition of a perfect couple and will be the forever couple that gets married. Some of us don’t want to hear it anymore.”

Owen and Ashley went to the homecoming dance together, but in early November, he called Ashley and asked to break up. He said he was sick of fighting and the texting had driven down trust. Ashley, he remembers, asked whether they could just take a break. Both cried. To Owen, breaking up was also tactical: He hoped it would satisfy the harasser and they would be left alone.

They kept the breakup quiet at school, but in the days after, the cyberbully started declaring victory:

he already chose us not u. He wont be with u this weekend so don’t even ask …

maybe u shouldn’t have picked cross country over him, u proved he isnt important to u, we were there tho … u dont get with him in bed, u don’t sneak out with him, u fucking dress awful aint no guy want that

In the weeks that followed, the cyberbully betrayed an uncanny knowledge of mundane goings-on at school. One morning before a Friday-night football game, they called out Ashley for showing up to class wearing Owen’s jersey. 11:44 a.m.: “WTF! U need to take that shit off … u are embarrassing him … ” When girls’ basketball season geared up later that November, three freshmen moved up to varsity, but Ashley stayed on JV. A senior overheard Kendra saying to students in the hallway that the only reason those girls made varsity was because their parents were friends with the coach. But the bully rubbed it in: “u suck at basketball, he ain’t datin no suck ass anorexic not good enough JV girl.”

At school, paranoia set in over Ashley. “She thought it was one person the whole entire time,” Owen says. Khloe Wilson was, in many ways, Ashley’s opposite: muscular with long dark hair and a natural confidence, whether on the volleyball court or in a garage Ping-Pong match. She was one of the freshmen who had moved up to varsity basketball. And the notion that Khloe could be a romantic threat wasn’t far-fetched, either: Both she and Owen say they did have off-and-on crushes on each other that school year. At lunch that fall, Ashley would sit at the same table as Khloe and her friends, a group of popular athlete girls. But Ashley grew afraid, Jill says, that some of these girls were the ones tormenting her — the texts often invoked a “we” (“we all hate u”). The girls didn’t much want to talk to Ashley either, let alone text her, for fear of getting pulled into the drama.

Owen, too, grew vigilant about who might be listening to him, terrified his words would be recycled into taunts, which often claimed to know his thoughts. He didn’t want his classmates to see how much the cyberbully bothered him, like when they called him names like “pussy bitch.” Jill sensed the fact that the bully seemed female deepened the shame. He’d always been happy-go-lucky, but now he’d plead some days to stay home from school.

On November 30, 2021, Jill saw the news about a 15-year-old near Detroit who had brought a semiautomatic pistol to school and murdered four classmates. She found herself thinking of Owen and Ashley pushed to their limits. When Jill told Kendra she was going to meet with a sheriff’s detective about the bully, she recalls that Kendra didn’t hesitate, saying, “I’ll meet you there.”

From certain angles, Kendra resembled a modern-day Super Mom: a “had-it-together, knew-what-she-was-doing kind of person,” as a local parent puts it. Kendra was the breadwinner, working as a bank-branch supervisor and eventually in human resources at Central Michigan University, while Shawn changed oil at a local auto-body shop. Shawn was a devoted father who took Ashley hunting, cheered her on at games, and coached her teams, but Kendra was the one who kept the family’s life ticking, overseeing everything from Ashley’s schedule to the family’s finances. His co-workers at the auto-body shop would joke about Kendra being his sugar mama. “We would say Shawn couldn’t dress himself without her,” says one. “It didn’t seem like anything malicious; he just let her do it all.”

In the spring of 2019, when Ashley was in sixth grade, Kendra got a new job at Ferris State University, a 40-minute drive away. The role was on the IT -service desk as a specialist in cell phones, and she told her family that it came with a huge salary bump. A few months into the job, during the fall that Ashley and Owen started dating, the family upgraded to a four-bedroom rustic-chic log cabin in the woods, which Shawn called his dream home.

Among themselves, locals started to speculate something was off. Over the following years, oddities stacked up: At the auto shop, Shawn would unquestioningly pass along tidbits from Kendra — say, that the family had missed house payments because someone in New Mexico had stolen their identity or that his pickup truck had been repossessed because of a scammer in Saginaw. After Kendra’s check bounced for her portion of a spring-break condo, she explained that she had gotten hacked.

When the parents met with the sheriff in January 2022, the McKennys were struck by how little Shawn seemed to know about the cyberbullying. His wife, on the other hand, had taken up the issue with zeal. That winter, still coaching eighth-grade basketball, Kendra would trudge up to the high-school coaches to talk about the texts, warning that the bullying could throw off Ashley’s focus on the court. The coaches would commiserate and suggest solutions: Could the Licaris change her number? Hold on to her phone? But Kendra never seemed to take their advice. Instead, she would come back the next day, drained, to discuss it again. She sought support from anyone who would listen — another mother running the scoreboard at the basketball games, parents who barely knew her. She would text the Antcliff twins, asking them to leave class to comfort Ashley when she was crying in the bathroom.

Students would sometimes see Kendra parked in the school lot in the middle of the day. She told people she worked for Ferris State from home and often showed up wearing the university’s gear. In the hallways one day, Kendra told Owen’s younger sister, Macy, that the bully had insulted Ashley’s shirt, so she was bringing a change of clothes. Another time, Kendra saw Natalie Antcliff in the parking lot and confided that it had taken hours for Ashley to get dressed that morning, that she was anxious about her performance at games because she expected it to become fodder for bullying. Natalie gave Kendra a hug, assuring her that the culprit would eventually be caught.

After their children broke up, Dave McKenny had sent Kendra a long conciliatory message: “I don’t think this means we can’t still get together!!” As it happened, the escalating texts gave them an urgent reason to keep talking. At Owen’s basketball games, Kendra still sat by Jill, sometimes prodding her reluctant daughter to show Jill the latest texts. On nights when the taunts were particularly vicious, Jill texted Kendra to check on Ashley in her bedroom. Other nights, the two mothers called each other, strategizing about their sleuthing. Jill sensed Kendra was still upset about the breakup: Kendra would ask if Jill thought their children would get back together, if the breakup was just because of the bully.

On their calls, Kendra and Jill would circle the possibility that Khloe was behind the texts. Jill found the case persuasive. Several anonymous complaints against Khloe had trickled into Ok2Say, the state’s tip line for potential threats to students — one in middle school about yelling at a teammate on the court, another that year about Owen helping her during a test in computer class. Khloe often said “bruh”; so did the texter. Khloe’s father was a police sergeant; the texter mentioned they had cops to defend them. Kendra once complained that Ashley’s Snapchat was hacked, and when she’d contacted the social network, Kendra claimed, it told her the login came from Broomfield Township, where the Wilsons live. One weekend, the texts came from the 906 area code — Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — where Khloe was snowmobiling with her family.

Every night, Owen handed his cell to his parents, and Jill and Dave would lie in bed, reading the latest messages, analyzing the language and references. Jill would call the numbers, cuing an automated message from the burner apps. Or she sometimes pecked out a reply as Owen: “kind of pathetic you keep hiding behind fake numbers and repeating over and over.” (“If it looks neat and very English-y,” Owen later said of the text log, “it was not me.”) Once, while going through his phone, Jill texted Khloe, pretending to be her son to test Khloe’s reaction: “If this is you be honest.” Khloe FaceTimed Owen angrily. Owen, trying to navigate the mess without losing friends, iced out his mother for days.

Ashley, for her part, would sometimes confront Khloe by text, asking her to air any issues to her face. But she still sat, awkwardly, with them at lunch and fell so silent — a “ghost friend,” one classmate tells me — that the main time they heard her talk was when she whispered a timid “here” during roll call. Ashley would complain to her father that because of the texts, she didn’t have any friends anymore. Still, she had one unwavering defender. In class, Ashley would often be texting; she told people she was writing her mother. At basketball tournaments, she sat by Kendra.

As principal at Beal, Dan Boyer prided himself on running a tight ship. “I’m pretty good at figuring things out,” he said. When Kendra and Jill first met with him and the superintendent in December 2021, he started by poring over the texts. Earlier ones were complete sentences with proper capitalization (“You didn’t get invited to sleep with him, I did”). Not how kids text. Later ones got looser, using phrases like “bruh,” “sry not sry,” “wtf,” and “rn.” Boyer started showing the messages to teachers who read student writing and coaches who text with them. For a few days, Boyer had Ashley text him whenever she got a message in class. Boyer quickly texted the teachers to scan for students on their phones. Nothing conclusive.

In early January, Kendra sent Boyer a numbered list of the investigative steps she understood he had taken and asked him to detail any others. The McKennys and Licaris wanted to address the girls’ basketball team — Khloe and other suspects were on it — and their parents directly, but Boyer refused; he didn’t want a scene of emotional parents accusing children. He did, however, humor the mothers’ request for a sting operation after Kendra complained that Ashley’s necklace and jersey had gone missing — odd, Boyer says, in a school where “it’s like 1960s America. Kids don’t lock their lockers.” During basketball practice, Ashley’s shoes were placed in Beal’s sports foyer under surveillance cameras, and Boyer emailed Kendra like a cop at a stakeout: “We are all set to track the shoes.” The shoes sat untouched for hours until a custodian put them in the lost and found. Still, in reviewing footage from the gymnasium, one thing did grab Boyer’s attention. During practice, Coach Kendra was often head down on her phone. She usually carried two: one she said was for work, one personal.

Again and again, a tug-of-war ensued between the school and the parents about what power they had over the children’s phones. Each teacher set their own policy, and students were always sneaking peeks in class. The McKennys pleaded for a new policy that phones stay in lockers, so Owen and Ashley could focus. The school pushed back: Parents wouldn’t tolerate it; they wanted a direct line to their children for emergencies. Boyer instead asked the parents to change their children’s numbers. But Jill argued that as soon as Owen’s new number appeared in a group text, the cyberbully would see it. Other parents wondered, Why not just take the phones away? But that was how Owen stayed in touch with coaches and travel-league teammates at other schools, how he accessed assignments in Google Classroom, his lifeline to being a normal teen. “They don’t even know how to function without it for an hour,” Jill says.

Each experiment failed to bring in a lead, so the school brought in the sheriff, Michael Main.

Craig Wilson, a police sergeant, wasn’t particularly intimidated when Sheriff Main called him in late January 2022 to explain that his daughter Khloe was a suspect. “I said, ‘If Khloe is doing this, we severely missed something as parents.’” Really, when did his daughter have time to be a prolific harasser, going from class to sports to homework to bed? What was in it for her?

When Craig and his wife, Tami, confronted Khloe, she was tearful, insisting that she’d done nothing wrong. Owen and Ashley had already been questioning her, and Khloe had grown so sick of it that she once gave Owen her phone the entire day so he could see she wasn’t sending the texts. Now, Khloe handed her phone to her father, who had cop colleagues download its contents. It came up clean.

In a meeting, the sheriff showed the Wilsons pages of messages from the bully that Kendra had sent to him. Some texts included a screenshot of Snapchat DM exchanges with someone named Khloe. Khloe said she’d never sent those: Someone had created a ghost Snapchat account to impersonate her. (She showed her father how easy that was to do.) Khloe recognized other words as hers, though: portions of her chats with Owen, which she’d screen-recorded and sent to Ashley to prove they weren’t flirting. Screenshotted bits of these exchanges were now, confusingly, also part of the bully’s messages.

Craig wasn’t officially on the case as a cop — Sheriff Main was handling it — but he wanted the truth fast. He and Tami had a hunch. Add it up: that weird texting in middle school about how Ashley wasn’t invited to their Halloween party. Kendra’s resentment of Khloe moving to varsity. A trivial incident at a basketball tournament years earlier, when Tami and another mother had searched for a sticky mat for what felt like an eternity while Kendra stayed mum, only revealing she had stowed it in the equipment room after parents threatened to look at surveillance tape. In early February, Craig texted the sheriff: “Honestly Mike I don’t know if you know Kendra or not but you really need to be cautious. There is a pretty good part of me that thinks that she may very well be doing this.”

Instead, as winter turned to spring, the sheriff dragged ten high-schoolers, whose names had come up in the investigation or in the texts, into the school office for questioning one by one. Some were Khloe’s friends. (“Thanks a lot mom,” Owen sarcastically texted Jill.) The bully had even started texting girls Owen was talking to at other schools. One night, Owen yelled at Jill that it was her job, as his mother, to make the bullying stop. Jill cried in frustration.

Everyone was reaching their breaking point. As softball started in the spring, the Antcliff twins would see Ashley crying on the bus to games. Kendra would sometimes send them screenshots of the bully’s texts — like the one that said, “all our lives would be better with you not here.” Natalie Antcliff worried every time Kendra would text or call that it would be the text or the call saying that Ashley had tried to hurt herself: “How much can a little girl take?” Natalie thought it was Khloe — “Everyone thought that,” she says — but also thought it was crazy for any teen to keep a secret this long.

Meanwhile, Khloe felt herself wilting under the suspicion. “This isn’t trying to sound cocky,” she says, but before the accusations, “I just feel like a lot of people liked me” — the children she coached at volleyball camp, upperclassmen on her teams, coaches. Khloe tried to keep a confident front at school, but when she got home, she’d close the door of her room to cry.

Tami and Craig Wilson weren’t alone in doubting Kendra. Little by little, people around town had started whispering about her, about the attention she seemed to continually seek. Another parent, flipping through the pages of texts with the Wilsons, concluded, “This is an adult. I wouldn’t put it past Kendra.” Beal’s secretary, Diane Fussman, told Principal Boyer she suspected her, which Boyer found implausible. (“I always thought she was a little obsessive with her child,” Fussman said. “My gut told me this just isn’t one of our kids.”) Sheriff Main ran the theory by Jill and Dave McKenny: Could it be Kendra? “Absolutely not,” Jill said. Another mother in town recalls the same thought flickering through her mind, then scolding herself, “How dare you think a mother would ever do that.”

Officer Brad Peter works on the Mid-Michigan Computer Crimes Task Force, a partnership between the FBI and local law enforcement. His police badge is from Bay City, an hour to Beal City’s east, but the FBI has deputized him to investigate digital crimes. When Sheriff Main asked him for help in April 2022, he knew he’d need to move fast. The burner apps held on to new subscriber records for about two weeks, so Peter asked Jill to send him the texter’s latest phone numbers daily.

Peter also emailed Kendra about the case. (Sheriff Main had relayed people’s suspicion of her, but Peter says they both found that notion far-fetched.) After two days of silence, Peter called her and proceeded to have what appeared to be an utterly normal conversation with a worried mother, talking about the toll on Ashley and musing about suspects.

In mid-April, Jill sent Peter four new numbers — one used on Easter Sunday at 6:28 p.m. The Pinger app replied to Peter’s search warrant: One number connected to Verizon network IP addresses out of the Ann Arbor and Detroit areas and another to a server for the Beal schools. The school had boosted its Wi-Fi into the parking lot since COVID, when some students studied in their cars. Peter emailed the school’s IT director: “I know that it’s someone from the school doing this, just can’t figure out who.” Beal’s server logs didn’t go back that far. Dead end.

Gradually, Jill was starting to pick up on strange signals from Kendra. Months after the breakup, Kendra kept prying into Owen’s love interests — asking if he was dating Khloe. (Annoyed, Jill firmly told her that they’d talk only about the bully going forward.) In early May, long after basketball season was over, Dave spotted Kendra’s gray Explorer parked near the Catholic church half a block from school; inside, Kendra was looking down at her lap. She glanced up at Dave and waved. Later that day, unprompted, Kendra brought it up to Jill on the phone. “Oh, I’m sure Dave thought it was funny seeing me in the parking lot,” she remembers Kendra saying. “I drove to Beal to get gas and got a coffee, and I spilled it all over me and so I pulled in there to wipe it off.” Jill sniffed a lie. But why?

Meanwhile, the bully was scraping bottom with nowhere worse to go. Back in November, the bully had told Ashley that Owen “said his life would be better if you were dead.” Then, a half-hour later, they took it back: “sry I shouldn’t say dead that was too far.” But in mid-May, there were no apologies: “KILL YOURSELF NOW BITCH.”

The following week, Peter got word from Verizon about those IP addresses that the bully’s number had connected to over Easter weekend from Ann Arbor and Detroit. Peter opened the trove: Hundreds of phone numbers had connected to those addresses over the next two days. He dug in, searching for all the numbers he had from people related to the case — including the parents.

One number, and only one, appeared.

Two months later, in August, Sheriff Main turned onto the gravel driveway of a beige ranch home. It was Shawn’s mother’s place. As the sheriff drove up, Kendra was hauling out the trash. Main and a detective stepped out of their car. They were there to seize Kendra’s devices.

What happened next is memorialized in the flat, procedural voice of the sheriff’s investigative log. (Main denied requests for an interview.) The sheriff handed Kendra a search warrant, saying she was being investigated as the cyberbully. When she denied it, the sheriff told her to be honest: Her number showed up each time a text was sent. Was she infatuated with Owen? Kendra said “no,” nothing like that. The sheriff demanded that she explain. Finally, something shifted. Kendra — “very uncomfortable,” the sheriff wrote — claimed that the initial texts did not come from her. But, she said, “she fed off from it and began to send them.” She said that a group of kids really was trying to come between Ashley and Owen. But why, Main asked, did it continue? Stress and financial issues, Kendra said.

Ashley was there, too, and after the sheriff told her what they’d found, she dialed her father. A co-worker at the auto shop remembers Shawn red-faced and in shock, stammering, “They think it’s Kendra.” He raced home in a loaner car. The sheriff intercepted him outside, and Shawn told him that his wife owned a third phone and had been evasive when he asked about it. That device, a gold iPhone, was nestled in a stack of wood outside; Kendra had stashed it there when the sheriff drove up.

That day, the sheriff delivered a second blow. Kendra, the family’s breadwinner, hadn’t worked in a year.

There was a lot about the family’s finances that Kendra had hidden. Her job change in 2019, when Ashley was in sixth grade, was, in fact, the result of Central Michigan University firing her for her performance. The new job at Ferris State had not come with the big wage bump she’d claimed, and collectors were filing suit in court for unpaid utility and insurance bills. Later that fall, when Owen asked Ashley out and the first texts arrived, the Licaris’ one-story house was foreclosed on. Kendra told her family she had sold it. The Licaris moved into the log cabin after entering into a land contract — a way to buy a house, often for those with bad credit, in which buyers pay installments directly to the owner.

By the spring of 2021, Ashley’s eighth-grade year, Kendra’s managers at Ferris State had put her on a performance-improvement plan, citing “excessive time” on nonwork texting and calls. She told them she was “overwhelmed and stressed out” from COVID and sports. The August of Ashley’s freshman year, falling short on her performance plan, Kendra quit. Throughout that school year — as the texts rained in at all hours — Kendra maintained she was working from home, feigning work calls when Shawn was around. According to a family member, whenever he would ask Kendra about anything financial, she would change the subject to the cyberbully.

During Ashley’s freshman fall, after a series of excuses from Kendra about PayPal and cashier’s-check hiccups, the cabin’s owners started the eviction process. In April 2022, just before the FBI-affiliated task force got involved in the case, the court received a request from the Licaris to delay getting evicted from their cabin. They were weathering unemployment, the letter said: “We do not have any other place to go and are completely terrified of being homeless with our daughter.” The court evicted them that month. Kendra told her family that the house’s foundation had cracked and they had to move out while it was lifted up for repairs.

News of Kendra’s confession rippled through Beal. After Owen’s football practice, Jill and Dave called both children to the front porch. Owen remained quiet, staring out at the yard in shock and anger. “I didn’t show a lot of emotion,” he says. “But on the inside, it was definitely super-loud.” Paige Antcliff, getting the call from her boyfriend’s mother, broke down in an auto lot where she was getting her first car for college, feeling used. Khloe put her parents on speaker while standing in a friend’s kitchen. The girls screamed in relief. After Kendra was arrested in December 2022, a student saw Ashley loading stuff from her locker into her book bag. She finished sophomore year in an online school, alone behind a screen.

The following spring, Kendra pleaded guilty to two counts of cyberstalking. At her sentencing, Kendra read from a typed page, her voice wracked with sobs: “I am sorry for my behavior to Owen McKenny and his family. I am sorry for my behavior to Khloe Wilson and her family. I am sorry to my daughter, Ashley, and my husband, Shawn.” Kendra continued, explaining that she had now learned through months of counseling that she had a mental illness — she mentioned depression, anxiety, and suppressed childhood trauma, “including sexual abuse” — and was “unaware that I was in crisis for many years.” The judge sentenced her to 19 months in prison.

Even now, Khloe says, “all I want to know is why she did that.” Owen remains puzzled, too. Was the bullying an attempt to draw him and Ashley closer together? Or, what actually happened, to drive them apart? “It’s just super-confusing,” he says. To Principal Boyer, her likely motive was “keeping her kid close to her, eliminating threatening relationships.” Significant in his mind: The texts started when Ashley hit seventh grade, when girls start pulling away from their parents. According to one of her attorneys, Kendra insisted that she didn’t send the first texts but saw how they made others rally around her family. So she continued, he said, “then it just got out of hand.” The picture, pieced together from different accounts, supports this notion: No matter how the texting began, at some point the light switched on — that an anonymous bully would offer Ashley and Owen a common enemy, bring attention to her quiet daughter, make Kendra into even more of a Super Mom, maintain her social alliances, distract from her mounting financial problems, and occupy the empty hours. “It was a blessing that I was caught,” she said at her sentencing, “because it forced me to stop.”

When the superintendent broke the news to Boyer, Boyer observed, “it’s like cyber-Munchausen’s.” Boyer didn’t know it at the time, but the phenomenon is one psychiatrists have been tracking for decades. In the ’90s, Dr. Marc Feldman, then an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who specializes in Munchausen syndrome, was told about a man claiming to be a Catholic monk in an online support group. The man posted about his fast-progressing cancer and how, given his vow of poverty, he couldn’t seek any treatment. At first, people in the group offered sympathy, but over time some grew suspicious. When someone finally challenged him, the man admitted it was a hoax — he wasn’t a monk and had never had cancer.

Feldman saw the monk as a twist on his clinical specialty. Munchausen’s is a mental-health disorder in which patients feign or purposely induce medical problems. The motive is partly to gratify an emotional need: to marshal the support and attention reserved for the ill. The behavior often feeds on itself, becoming addictive or compulsive, according to patients. People who struggle to define themselves tap into an instant identity — patient. Victim. Hero. In 2000, Feldman wrote a paper on the disorder, calling it “Munchausen by internet,” and has watched its manifestations track the advance of tech — from the early online forums to those feigning diseases on GoFundMe or Tiktok.

Munchausen experts think the digital variety will likely become the most common sort. Ruses are easier on the disembodied internet. No one needs to get physically hurt. In 2017, Feldman joined colleagues to study the phenomenon among undergrads: About 2 percent of the responding college students admitted to bullying themselves under an alias, and another 2 percent reported faking an identity to bully a friend online and then, as themselves, heroically coming to the friend’s defense. Feldman helped revise the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to acknowledge that the condition can play out partially or entirely online. Deep in the 2017 study (which was never published), the Alabama researchers predicted where the trend could lead: parents cyberbullying their own child, “in the same way that some parents feign illnesses in their child to satisfy their own psychological needs.”

After Ashley returned to Beal City for junior year, Owen avoided her. He even felt angry toward her. So many in town asked: How could she not have known? Khloe and her parents thought Ashley must have known. Why had she always been texting her mother in class? Natalie Antcliff, who got back in touch with Ashley once she returned to town, says yes, Ashley had started to consider that her mother could be the bully. But only in the last month before the sheriff showed up.

After many interview requests, Kendra wrote me from prison. She thanked me for seeking her side of the story and said she’d be ready to talk after her release (then never replied again). In her email, she said:

“I do ask, that you truly think about the kids (minor kids) that are involved in this situation, including my daughter, who is trying to move forward and has a bright future ahead of herself … These stories, are doing additional harm to her, I can handle the pain, but she can not and does not deserve it. She is moving forward with life and doesn’t deserve to be put in the spotlight any more (or having people thinking her mom is a villain, as that is hard mentally and emotionally for her).”

Kendra was released last August. Shawn had divorced her and received full custody, and she is living with family near Detroit, reportedly allowed even less contact with her daughter than when she was in prison. This May, Ashley, Owen, and Khloe will graduate from Beal City. Khloe Wilson signed a college volleyball deal in the school’s trophy-lined foyer. Owen — senior homecoming king — made a soaring catch in the end zone for a touchdown during the state football final, which he memorialized on Instagram. His younger sister, Macy, still sits with Ashley at lunch, with a tacit agreement to never mention the cyberbullying.

It would have made a nice ending, but this is the age of the true-crime content machine. While Kendra was still in prison, Lifetime released a movie loosely based on what happened in Beal; titled Mommy Meanest, it stars Lisa Rinna as a Machiavellian brunette mother harassing her daughter. And last year, a crew from Campfire Studios, a glossy Los Angeles–based production company, came to central Michigan to film. (“Everyone was like, ‘Oh, are you talking to ’em? Are you talking to ’em?’” says one mother.) Word around town is that nearly the full cast of the saga sat for interviews, including Kendra, Ashley, and Shawn. The Beal City school board wouldn’t let Campfire film on-site, so the crew and many sources trekked to a city hall in a nearby town. For B-roll, Boyer and the superintendent stood on the sidewalk and chatted, “like we’re talking this through.” The documentary is expected to premiere this year on Netflix. (Campfire Studios declined to comment, and Netflix did not respond to a request.)

At the Wilsons’ last Halloween party, Tami dressed a scarecrow in a prison jumpsuit and a mask of Kendra’s mug shot, phones clutched in its gnarled hands. At one point, she pondered gathering friends in Beal for a big watch party of the documentary. Then she changed her mind: Maybe it would be too emotional to relive this whole thing again. Maybe best, she said, to just watch it as a family.