This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

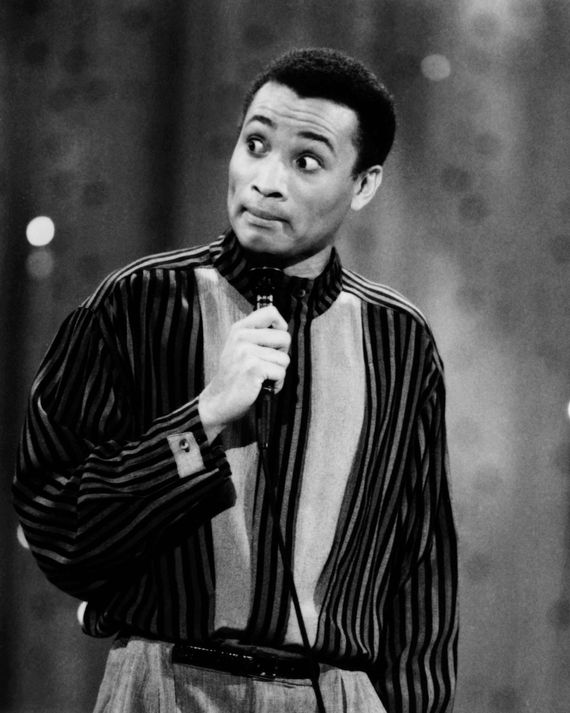

If at any point in the past 30 years you were amused by the high jinks in a Black sitcom, chances are Larry Wilmore had something to do with it. Raised in a tumultuous household in the East L.A. suburb of Pomona, the high-school athlete turned theater geek had been touring the Southland as a stand-up comedian for almost a decade when he joined the writers’ room of a new series called In Living Color. The show became a cultural cornerstone of the early 1990s, launching the careers of Jim Carrey and Jamie Foxx and giving Wilmore a role model, in showrunner Keenen Ivory Wayans, for what would become his career mission: putting Black creators in control of Black TV. That was just the beginning of the golden age of the Black sitcom, and Wilmore, along with his younger brother and fellow comedy writer, Marc, played key roles in how it unfolded.

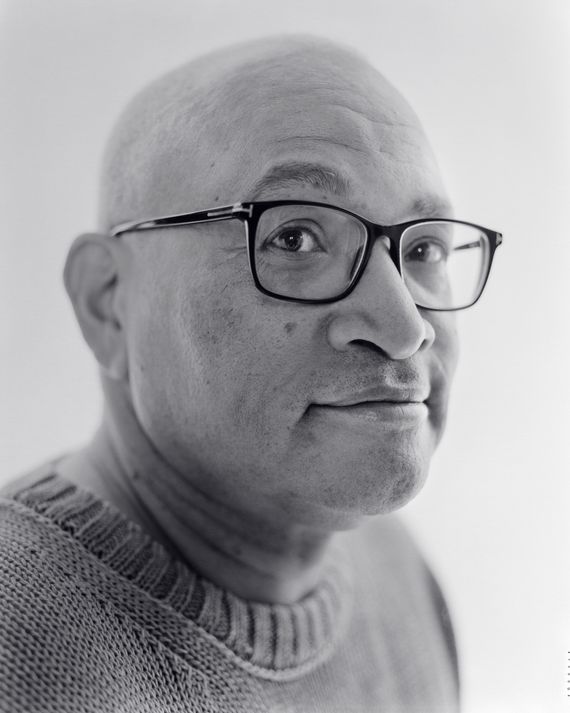

Younger audiences are probably most familiar with Wilmore, now 60, from his hosting gig on the short-lived satirical news program The Nightly Show — a racially pointed spinoff of The Daily Show With Jon Stewart, on which Wilmore played the senior (and only) Black correspondent — or the glowing praise he has since received from his mentees Issa Rae, Robin Thede, and Quinta Brunson. But he earned his stripes as a writer, creator, and producer on beloved comedies like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (“a mess”), The PJs (“One of the best shows of all time,” Chris Rock told him), and maybe most notably The Bernie Mac Show. His 2002 Emmy win for the last made history: Wilmore was the first Black TV writer to triumph in the comedy category — only for his “mole” at Fox Television to uncover a plot to oust Wilmore shortly after. (It was successful.) On the morning before his daughter’s Barnard graduation in May, I met Wilmore — genial, bespectacled, unexpectedly fiery — for coffee, during which he spent several hours reminiscing, laughing, and shaking his head about the past three decades in comedy TV.

Were you always a performer?

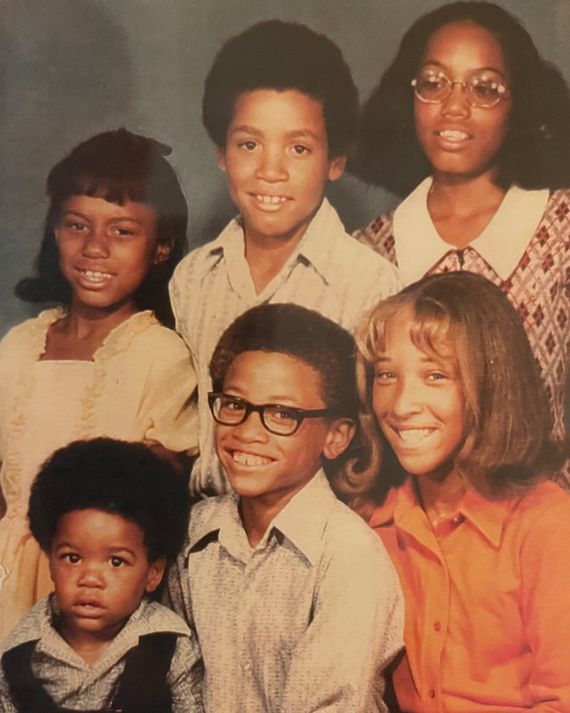

Marc and I used to go to bed at night trying to make each other laugh. Some of the backdrop of that is we could hear our parents arguing, ’cause they were going through a divorce; I remember once hearing a vase crash against the wall and being like, “Oh.” Meanwhile, we were both good at characters, so we would imitate the people around us. We had some neighbors next door; we called them Uncle Henry and his wife B.B., who were from Texas. Henry would give advice like, “Larry, you have to have a spare.” I’m like, “What do you mean?” He says, “One girl leave, what are you going to do? You got nothing.” We’re 9 years old, and he’s telling us we need a side piece.

What was Pomona like when you were growing up?

It was a very Black middle-class place when my parents first moved there. My father was a probation officer. Those were the jobs they could get before they could get real professional jobs, you know? You saw a lot of people who were in civil-service jobs.

You’ve told a story about a formative experience you had with racism there involving the police.

We were hearing some cops next door, so we rushed into my sister’s room and looked out the window. It sounded like they were banging on the door, and I remember the cop just said, “Freeze, nigger, dead!” As in, “You’re going to die in a few seconds, and I have the authority to do it with impunity.” My brother and I used to talk about it all the time, but we talked about it in jokes, like a kid would do, not realizing what those words really meant. It wasn’t until I was older that it was like, Man, the weight of those words together sums up so many things we see today.

Did that experience complicate your understanding of what your dad did for work?

I had a different experience with law enforcement because of him. I wasn’t anti-police; I was able to compartmentalize bad behavior because there were so many Blacks that worked in law enforcement, including his friends in the probation department. I’m saying this now looking back. I remember my dad getting pulled over a couple times, and he would open his wallet, and as soon as that badge was shown, they were the nicest people in the world. To me, the power of that star was like a magic trick. So I’ve always viewed the cop issue not so much in terms of race but in terms of power dynamics. Black people and other people can be seduced and drunk with that power as much as white people.

Your dad became a doctor later.

The wrong person to become a doctor — like, zero bedside manner. He felt that Rodney King wasn’t beaten hard enough.

When you did stand-up on Comic Strip Live in 1990, you were introduced as wanting “to be like your father: cold and insensitive.” There’s clearly some truth there. Do you think his job brought that out in him?

That’s hilarious. No, that’s just who he is. My mom is overly emotional. My dad — a plane could crash into the house next door and his reaction would be, “Hm. Evidently man was not meant to fly.”

Obviously dark but also funny. Were your parents funny people?

Oh, completely, but not in control of it. They were just funny characters. Growing up with them is why I’m in comedy.

I recognized later in life that my mom had a nervous breakdown when I was a kid. Where I relate to the world probably starts there. You’ve seen your mom suffer; you don’t want to see that for others. My sisters had run away several times — that was their rebellion against everything. My father worked at a juvenile home, and both of my sisters went to juvie. We were at our lowest point, including money-wise. And I’m the oldest at home basically feeling like I got to take care of all this other stuff.

How does that hardship turn into a career in comedy?

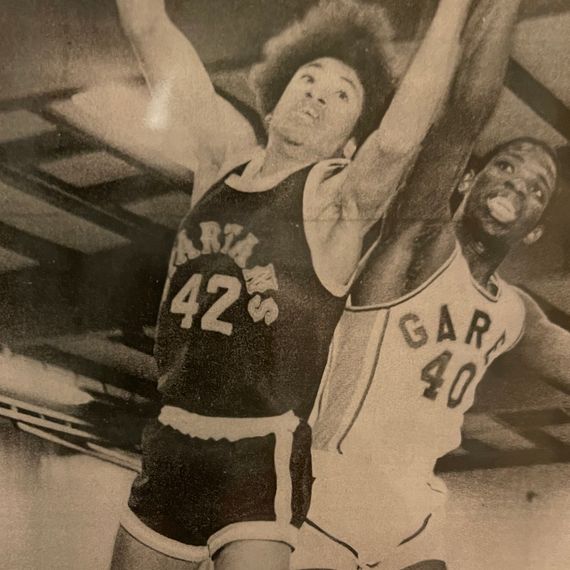

My last couple years in high school was me just trying to find escapes, so I escaped into sports and theater. My academic career pretty much went to the toilet. I was lucky when it came to sports, because I was really good, but we lived in a sports neighborhood, too: Billy Duffy, Greg Ballard, Cornell Webster. This was just that little corner of my neighborhood, let alone all of Pomona back then. At a young age, I could see what it took to be an elite athlete, and you knew if you were that or not — you couldn’t delude yourself. So I was like, I’m going to devote myself to theater and see what happens.

Do you remember your first time performing stand-up?

I thought I was ready to audition at the Comedy Store. I’d never done stand-up before — maybe at a high-school talent show — and I lied about my age. I think I might have been 16 or 17. I went up onstage, and I had memorized some little routine from an old comedy record, just did impressions. And I got big laughs. I don’t know if people knew what I was doing, but they called me back and said, “That was great. We want you to come back and showcase for the owner.” It was two weeks later, and I remember getting sick as a dog. Everything that went right the first time went horribly wrong the second. The audience didn’t laugh a bit. And, of course, the owner of the club knows I’m doing someone else’s routine — I didn’t think about that at the time. People who, the first time, were like, “Oh, you’re so good!” — no one wants to look at you now. This is how cold stand-up is. There’s death all over you. It’s just the worst feeling in the world. It took me three or four years to try stand-up again after that.

But I knew I had to. Once I really started doing it, after about six months, I was working regularly in places, and I was headlining clubs in two years. And that was just writing jokes every day, so it put me in control of my career rather than being at the behest of the whims of the business. When I say it’s important for us to control our own futures, our own fate, and talk about who gets to control the narrative about something — that’s what stand-up taught me. It was the only way I could work. I wasn’t Denzel.

Your first TV-writing gig, in 1990–91, was a late-night show hosted by Rick Dees called Into the Night.

When I got that job, I was 28, 29 maybe, but I was a seasoned stand-up comic. I knew who I was, and I knew I could be funny. The job only lasted six months, but I just wrote at my leisure. I used to write jokes for the comedians, really as a favor. I was making a transition at the time where I kind of abandoned the stand-up route. I couldn’t get auditions for things that were right for me, or they just didn’t see who I was — I wasn’t the Def Jam type of comic. You had to be from the ghetto, that type of thing. God forbid you be a smart Black comic or talk about politics. That’s reserved for white people, which wasn’t the case when I was growing up. Dick Gregory was smart. Redd Foxx was what they called “party records.” Bill Cosby just told very clean stories. Godfrey Cambridge was like a hipster, talked about culture and race. You could be in any lane. But then in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Hollywood pushed us into one lane. That’s when I decided I needed to write and produce and create a space for myself.

You’ve said you initially were more indebted to Jewish humor than Black humor.

My dad took us to see the Marx Brothers, who were going through a revival in the early 1970s, on the big screen. Animal Crackers was showing, and I was like, “Oh my God, this is the funniest thing I’ve ever seen.” He was also into old radio, and he had some 8-tracks of the old Jack Benny show, and my brother and I used to listen to them. Redd Foxx or Richard Pryor — those weren’t the rhythms in my head at that age. That became a content thing later but not a rhythm thing.

Your second TV-writing job was In Living Color.

It was the biggest thing on television at the time because it really was a culture changer. By the way, I wasn’t “urban” enough to audition for the show, but I was good enough to write for it, which is interesting. You see more Black comics that have different rhythms now, like Jerrod Carmichael. Now, it’s not a big deal, but he couldn’t exist back then. For me, In Living Color was the best kind of gig I could have — there’s a lot of conceptual stuff going on there, funny observations, so many layers in it.

From what I’ve read, it sounded like the work hours were — I think the quote was “insane, possibly illegal.”

Thousand percent true. It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.

What did your day look like?

Often I’d be there till three in the morning, working on weekends at home, having to come up with pitches. People got fired all the time. We called Keenen “Murphy Brown” because he had a new assistant every week. It seemed like, Oh, they didn’t make his oatmeal right this week? They’re getting fired. If you had a bad pitch, Keenen would mime putting bullets into a gun chamber, and we’d go, “Uh-oh, it’s in the chamber!” And he’d just knock you out, and you were like, Oh shit, not knowing if you were going to get fired or whatever. But it was a lot of fun.

It’s a legendary Black cultural moment, but looking at the credits, there were a lot of white writers, maybe even the majority.

That’s what Hollywood was.

What was the process of assembling that room?

That was Keenen. But let me tell you, it didn’t matter. Many of the white writers were very formidable. Les Firestein, one of the most brilliant comic minds; the stuff he pitched, you were dying laughing. Most of it was completely inappropriate. Matt Wickline started on Letterman and John Bowman started on SNL, and I think Matt originally came up with Homey D. Clown. So it really didn’t matter. The Black writers were more the newbies, because there just weren’t a lot of us in the business.

How does that balance influence what ends up onscreen? Did it feel at any point like there was tension?

Zero. We didn’t even think about it then. There were no cultural fences in terms of, “Well, you can’t write about that because you’re white.” Nope. All was fair game. It was really you got to bring the funny. It didn’t matter who you were. Keenen was extremely democratic in terms of that.

Do you still feel that way?

I’ve always felt that way. I mean, sure, there’s a nuanced conversation to be had about who should be telling stories, which is a different thing. But keep in mind Keenen was the head of that show. So he was controlling the narrative. We were the little worker bees giving him the honey. So who’s giving the honey is a little different than who’s controlling the hive. That was very powerful to me at that time — that Keenen did the show he wanted to do, and when he couldn’t do it, he left.

I saw a talk-show interview from shortly after the L.A. riots in which you said you had pitched a sketch about a restaurant in South Central called “Reginald Denny’s.”

I remember the “Grand Slam” breakfast. There was a kind of pride in writing jokes in poor taste. When Sammy Davis Jr. died, I wrote a sketch called “Weekend at Sammy’s” where it was like Weekend at Bernie’s.

Oh God.

Because Davis’s widow, Altovise, couldn’t pay the taxes, she had to pretend Sammy was still alive. She’s taking him around like, “Hey, man!” Doing all that. It was hilarious, but it felt a little too disrespectful. We ended up doing a Ghost parody instead, where the Whoopi Goldberg character invoked Sammy, and it turned out to be a sweet sketch. I remember some that didn’t make it more than the ones that did. I wrote one called “Compton Leap” — a play on Quantum Leap — about this brother who would jump into people but at the most inopportune moment. He jumped into the body of Rodney King right as he’s being pulled over. There’s nothing redeeming about that sketch. And that’s what I mean: The more inappropriate, the better. The writers tried to out-inappropriate each other.

You once told Bill Simmons on his show that people used to go to comedy in order to be shocked. Do you think of that as an ideal?

The primary purpose of comedy is to get laughs. When it serves that well, a lot of the other purposes become secondary or tertiary. If the audience sits there and they don’t laugh, they feel like the comedian has failed or the comedy has failed at its job. And different types of comedy serve different purposes. Maybe the purpose is to say things that are over the line. But it comes down to people’s tastes, and often what you agree with and don’t agree with, including from a political standpoint, fits one of those types, not just what you find funny.

Does that apply to you too? How do you respond to comedy that really clashes with, say, your political sensibilities?

I don’t mind. I don’t need agreement in order to see the value in something.

I’m thinking of Dave Chappelle and his jokes about transgender people, particularly since in the past you’ve described the LGBTQ+ community’s fight as “one of the civil-rights issues of our time.”

Chappelle is interesting. I don’t know what the right term is, but I think he’s revealing himself onstage. He’s granted himself a certain permission, and he’s speaking to the audience in a way that nobody else quite does. That’s a touchy subject, though. You’re not going to see me doing jokes in that area. My biggest reason is that any time there’s a group really feeling attacked, you’ve got to be careful. I would really have to have a good take on something to put myself out there with jokes.

Do you ever make professional judgments based off the content in comedy like that?

I’m not thinking about it like that — How dare they say that! I’ll never work with that person! I don’t have those conversations with myself. I’ve never had an opportunity to work with Dave Chappelle. So it would be silly for me to say, “Well, I’m not going to work with Dave Chappelle.” Nobody asked you to. If someone asked me, then I would have to think about it and consider it.

After In Living Color, you went into more traditional sitcom writing. I read a quote from Felicia D. Henderson, whom you worked with on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and she said the bulk of the job was answering white writers’ questions about whether a scene or story line felt true to what a real Black person would do. Is that how you remember it?

The year we were there was a mess. Jeff Pollack was not equipped to be running a show. He didn’t know what he was doing. Felicia quit and then I quit after that because I couldn’t believe she was brave enough to quit. I didn’t finish the sixth season. It was just terrible. I remember going up to Will Smith, and I said, “It’s nothing against you, man” — this is before he did Men in Black and everything — and I was like, “You’re about to blow up, but I can’t work with your boy, man. I got to bounce out of here.” He was very nice about it.

There were some writers on Fresh Prince — and I don’t remember their names, thank God — who just had that type of superiority thing. I’m sure Felicia felt that, too. We were just really disregarded. The second year of Sister, Sister, there were some guys running it who had a little bit of that bullshit. Those are the only two shows where I felt that. But I was determined to do more of what Keenen was doing: No, motherfuckers. I’m going to determine the tone in this thing.

The word authenticity gets used a lot to argue for more Black storytellers in TV. Is that the right standard?

I use a different frame than authenticity, which you can call anyone’s experience. For me, it’s about who gets to say what we see. Whose gaze is this? Is this a white gaze? Is it a Black gaze? Is it a male gaze? Is it a female gaze? For most of television, Blackness was seen through a white gaze. Good Times you could call authentic, but it’s white-gaze authentic. Even though the idea came from a Black writer, and God bless Norman Lear, that’s still a white man.

Us controlling the narrative is different than when the white executives are giving it their check mark. There was nobody saying, “Keenen, that’s too Black. You can’t do that.” That was a revolutionary act. There are more Blacks in the decision-making process now who get to say, “Yeah, you can do that kind of story. That’s fine.” Or even white people who are in those positions saying to the Black creators, “You tell that story. I don’t have a say in that.” That’s different now, too, as opposed to, “No, it’s got to be this type of thing.”

A kind of gatekeeping.

Here’s how it was expressed: Black writers were not on white shows. The only one from those days was Saladin Patterson, who got a job on Frasier. That was huge at the time. Never happened. When I would be at those Television Critics Association things when I was doing Bernie Mac, people kept asking, “Larry, how many Black writers on your show?” I said, “Motherfucker, ask the white shows how many Black writers they have! I’m the one with Black writers. Who the fuck are you asking?” I would get upset about it. Like, ask Friends, Frasier, all those shows. I’ve got more with just me than all those shows combined. And they would shut up at that.

I remember having a conversation with my friend Janine Sherman Barrois, who’s now a showrunner. We were working on Jamie Foxx’s show at the same time. And Janine was like, “Larry, how come there’s no Black Seinfeld?” Meaning a show that was considered Black but smart. And I said, “Janine, because you haven’t written it yet.” And then I go, “Wait, oh, fuck, neither have I.” That really motivated me to write The PJs for Eddie Murphy, to make something smart on TV and culturally important at the same time. It’s not just niggas being funny, you know? It’s smart too, niggas. Use that word, white people: smart. Say it.

The PJs is pretty different from what I remember the public narrative being about it when I was a kid. One of its early detractors, Spike Lee, said it showed “no love at all for Black people.” Is love a prerequisite for making good Black TV?

I disagree with the premise. PJs is a satire. So we’re shining a light on social situations, social interactions. Whether it’s something we agree or disagree with, it is what it is. I mean, we had a crackhead on the show.

You’ve said that was “seminal.”

It was actually just a TV trope. Andy Griffith had the town drunk; Taxi had the town drug addict. So we had the crackhead. But we also had jokes where Calvin said, “Juicy, man, I hope we never grow old.” And Juicy goes, “Well, the statistics are in our favor.” This is satire. It’s not supposed to be a love letter. The PJs was smart.

Black creatives have struggled for a long time with this debate of whether we are presenting an image that is going to be somehow used against us.

I don’t strategize against bad actors. I dramatize situations that have conflict because I’m a storyteller. Now, because I have a conscience and I have some responsibility, obviously my point of view is not to hang Black people out to dry. That’s not what I do. But I also don’t have to be precious with how I tell the story; I can be honest about it at the same time.

Do you think it was your most boundary-pushing show?

That I’ve created? Oh 1,000 percent. Absolutely. None that’s come close. There’s a lot of imperfection in The PJs, but it works as the satire it was intended to be.

You’ve spoken about watching a lot of French New Wave films as inspiration for The Bernie Mac Show.

Sure, for the pilot. I was also watching some reality television, like this PBS show The 1900 House, where they put cameras in a house in England and people had to live like it was 1900. It was fascinating. They had this confessional camera where they could tell us what they did during the day. I thought, What if I did a sitcom with this kind of form? Where it looked like we were kind of spying on a family. And when I saw Bernie do The Original Kings of Comedy about taking care of his sister’s kids, I thought, That’s a nice emotional thing. I pitched it to him, and he loved it.

And then you won an Emmy Award for the pilot.

It was hard to write at first. When you’re writing pilots, after you sell it, you’re supposed to turn in an outline, and the studio gives you notes on it and then you write the script. I never turned in an outline because I knew this had to be different, but I couldn’t quite get it. I wrote the same three pages every day for like four weeks. And I was scared to death. I’m like, Why did I pitch this stupid thing?

I had some tapes of The Real World, and I remember playing it and looking for the act break, where there’s a question about something and then we come back to get the answer. The Real World didn’t do that. They would just go to the commercial. I’m like, What’s going on? They’re not doing that manipulation thing. Why do I want to watch this? Then I realized, Well, maybe I’m just interested in this character and I want to see more of them. It turned a light switch on: Okay, I don’t have to have this manipulation. I could just be on a character’s ride. But I still couldn’t get past these three pages. Four and a half weeks go by and I haven’t communicated to the studio at all. This is a disaster. One day, I get to page four, and I go, Oh! And it all clicked. It poured out of me over the next 36 hours. That script ended up winning the Emmy a year and a half later. But if you watch it, there’s really no plot. You see him go on a journey. He’s confident in the beginning, and that confidence gets weaker until there’s an acceptance: I guess things are going to be different.

You were also fired from the show. It seemed like the network got what you were doing for a while, then abandoned it.

Trust me, no, they did not. In the bathroom one day, the head of Fox at the time, Sandy Grushow, told my mole, “Well, I guess we can’t fire him now.” That was his comment. Not, “Oh, we’re really proud of Larry.”

Who was your mole?

I can’t say. Even after all these years.

He’s your Deep Throat.

Exactly. He intercepted a lot of emails and stuff for me, too. I got one where they said they needed to separate me and Bernie. We were too close. Unfortunately, I lost Bernie’s ear because of his own demons or whatever, but I don’t blame Bernie for that. It was always a fight with them. This type of storytelling I was doing then everybody does now. But back then, there weren’t any single-camera shows.

We had an episode called “Hot, Hot, Hot.” And the execs go, “Well, what happens in this episode?” And I go, “It’s hot.” They’re like, “Yeah, but what happens?” And I go, “Um, it’s hot.” It made them so mad; they just didn’t understand. I’m like, “Bernie’s got to take care of the kids, and it’s hot; I don’t know what to tell you.” It really was that simple, and it turned out to be one of our more popular episodes.

That’s one of the things where if you have kids, you know.

Yes, absolutely right. All you have to do is think about it. You go, Oh, there’s the three acts.

So you’re making this show that’s successful, that’s critically acclaimed —

Didn’t matter. Who gets the benefit of the doubt at that time? Not Black writers. They considered me incompetent, like I didn’t know what I was doing. Meanwhile, I won an Emmy, two TCA Awards, Humanitas, a Peabody Award, Golden Globe nominee, Image Award. Every award you could possibly name meant nothing.

You don’t seem to me like you’re a disagreeable person.

They can turn you into an asshole. But no, I’m not a monster. I’m trying to make a good show. Grushow treated a lot of people horribly during that time. I wasn’t alone in that.

You were going through some personal stuff, too.

My marriage was breaking apart at the time. It’s just tough. If you really love what you do, you stick in there. But my career could have been over. I had small children, too. I was like, “I got to work. These kids got to go to school.”

Then you were an actor and consulting producer on The Office.

I started writing and producing back in the day to create a space for myself. The Office led me back to performing. When we did the table read for the “Diversity Day” episode, I got a lot of laughs. Ken Kwapis, who also directed the Bernie Mac pilot, is like, “Larry, you have to do this.”

But people don’t remember that the American version of The Office was not highly regarded. I went to England to do this seminar once with The Bernie Mac Show. Ash Atalla, one of the producers of the English Office, was there. He said, “Do me a favor: Make sure they never take this to America and ruin it.” I go, “I’ll tell you what — if it does, I’ll never work on something like that.” Smash-cut to me not only working on it, I’m in this motherfucker.

And then came The Daily Show, a different format altogether.

At the time, I was already thinking a lot about creating my own show to star in or going back to my stand-up roots and doing the talk-show thing. I’d written a script called “Fat Man, Skinny Wife,” which was my behind-the-scenes look at the sitcom from a Black-sitcom point of view. Of course, little did I know I’m competing with an instant classic like Tina Fey’s 30 Rock, or Aaron Sorkin’s Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, but that’s how TV works sometimes.

I thought, Well, I can’t just do a talk show right now. I haven’t done stand-up in a while, and I have to reestablish a connection with the audience. So I thought maybe if I did The Daily Show, I could start reestablishing myself as a personality.

The show was not diverse before you showed up.

Exactly. And I wasn’t a writer on The Daily Show. So when I would come in, they’d have an idea, but I would still hash it out with Jon. The pieces really were elevated because of those discussions and us deconstructing them.

It was like that from the beginning?

When I was doing my first piece, I was a correspondent. But what do you have in your head? Stephen Colbert being a correspondent. You can’t do an impression of him. You’ve got to find your own self. I didn’t know what that was yet. So I co-wrote the piece with the people there. We were trying to refine it. In rehearsal, I was supposed to do two different pieces. And they were going to show one that night and another one later. They both went horribly in rehearsal. I mean, terribly. I don’t think I got one laugh. It was kind of forced.

And I remembered that feeling from when I first did stand-up, people not making eye contact with me. It’s like when you don’t name one of your animals that you may have to eat later because you don’t want to get too close to it: I don’t think he’s going to be back. And I was a performer first and foremost, so that’s the worst feeling in the world. Then somebody came in and said, “Okay, Larry, here’s what we’re going to do.” And I’m fearing the worst, like, My one shot to be on The Daily Show and I’m going to ruin it. They cut the first piece. Jon says, “Hey, man, come on in here. Let’s just put this second one in our own words. It’s a little too writer-y.” So now we’re bantering back and forth rather than the formal process of writing the script. It was so much more free.

We were going to do that on TV that night in front of the audience. Jon just looks at me and says, “Hey, man, just fucking give it to America.” It was the best advice he could have given me. My stand-up instincts took over. It got huge laughs, and I’m like, All right. I’m in now. I could feel the team wondering, Well, where did this guy come from? This wasn’t the guy who was at rehearsal. Completely the opposite of my Comedy Store experience. Failure first, then wild success after.

It felt after a while like people were taking The Daily Show’s political comedy too seriously as a guidepost for how to interpret the actual political world. There was a New York Times piece headlined “Is Jon Stewart the Most Trusted Man in America?”

They gave him too much credit.

How much do you think he courted and even encouraged that?

Probably some. People wanted it to be actual activism. When people say, “Phone Jon Stewart — if he had said something, maybe Trump wouldn’t have been elected,” I’m like, No, that’s not how it works. Why are you looking to comedians for the most important decisions about the world? I have no problem with what Jon does in his show. It’s great. But it need not be our North Star.

How do you reconcile the fact that Trump, whom you have open misgivings about as a person and as a president, would also have been very good for the content you were hoping to create long-term with The Nightly Show?

Les Moonves got in trouble saying something like that. It’s always been a conflict. I used to say, “As soon as racism’s gone, we’re done here!” It’s part of the bargain of doing that type of humor.

How did it get so tense and ugly with Comedy Central? You said at a certain point they wouldn’t even talk to you guys and that later you felt a sense of Schadenfreude when the network couldn’t put together another late-night success.

I don’t mind being salty in cancellation. But we were up against some very tough things. People have to remember I was in the slot that Stephen Colbert had, and he had a very passionate, loyal audience. They put his show on a pedestal. And my show was, I think, ingested by a lot of that crowd as the show that replaced Stephen’s show. It was being judged partly from that standpoint. From the network’s point of view, it was, “Here are the numbers Stephen had when he was leaving” — not when he got there, but when he was leaving — “How come your numbers aren’t up here?” It was an uphill climb. I knew from the beginning there was no way I could compete with what Stephen did. I had to be my own thing.

It takes a while to find a show. Even Jon Stewart — who took over The Daily Show from Craig Kilborn — people weren’t pleased with what he was doing at first, and it took a while to turn that into his show. I thought what made our show special was we were having a conversation that America said it wanted to have. And I’m like, All right, motherfuckers. We’re going to have it. Comedy Central wanted us to do games and things like that. I think their point of view was they’re just trying to fix a show. But they never approached it like, “Is this show an expression of Larry Wilmore’s voice?”

By the time we were canceled, they weren’t interested in us. They hadn’t talked to us for months. We were pretty much finding what the show was at that point. And I think people really appreciated it. Many of our fans felt that we were a voice in the wilderness covering issues that others just weren’t covering. We were well oiled to handle any situation that came up in the news. We could have comedy; we could have discussion. It was built to have both, and we could keep it real in each format. And entertaining.

Do you feel like Trevor Noah’s iteration of The Daily Show was the network’s attempt to find a middle point between your show and Jon’s show?

Tell me what you really think, Zak.

I’m interested in what you think.

What are you trying to say exactly? Are you saying they didn’t want two Black hosts? Are you saying they didn’t want Black to Black? Is that what you’re saying?

I’m not saying that; I’m asking.

Oh, I don’t know. I mean, I think you should call them and ask them. I think it’s a very good question. Although I would like to be on the record saying I have never even considered that, and I just want to thank you for bringing that point up.

Noted. I rewatched your 2016 White House Correspondents’ Dinner set. Very icy reception.

Yeah. It’s very funny.

How much of that did you anticipate?

I didn’t know what to expect because it’s a tough room. I’m a comedian, and

I knew when I was in a hole. Believe me. And it started when I made a joke first about Joe Biden, and it got kind of an “Ooh” because everybody really loved Joe then. And I’m like, Ugh. And then I said the thing about Wolf Blitzer. I meant it to be sarcastic, but it came out more as just a straight fact. And so it was like, “Why is he picking on Wolf Blitzer?” And then part of me is like, Look — whatever, motherfuckers.

So I was done caring after that because I knew. I’m like, Well, I’m just going to have to barrel through this and do these jokes whether they laugh or not. You can see it looks like I’m really enjoying it, because in my mind, rather than do the thing where it’s like, Oh, you didn’t think that was funny? and fight them, I did the thing in my mind where I acted like they were really laughing and really enjoying it.

In the Washington Post afterward, you talked about skipping some jokes you had intended to make, and one of them was about Will and Jada Pinkett Smith — thanking Jada for not boycotting you like she did the Oscars that year. Did you know something the rest of us didn’t?

I could’ve gotten slapped! That’s hilarious. Who would’ve guessed that?

Is there anyone you wouldn’t make a joke about because they might rush onstage and slap you in the face?

Absolutely not. Nobody’s off-limits.

How do you decide whom you’re going to mentor?

I don’t have a playbook. I probably say “no” more than I say “yes.” People who have worked with me know that when I take them through the process, sometimes it can feel like therapy. I remember working with someone once — I’m not going to say who it was because we’re doing something right now — where she brought in an idea, and it wasn’t bad, but to me it was kind of surface-y. I knew she had more. And so I just started asking her questions about her life.

It became this thing where she came out to me. She wasn’t public about that. We just started talking about it, and I started investigating more, and I said, “Let me tell you what the show is that we need to do.” And at the end of that, it was a completely different thing. We laughed about that for a while. But if somebody’s saying something and I can tell it’s not authentic, I push that toward an authentic conversation. I try to be very respectful, too. Some people aren’t up for it, but it’s amazing how many people are. And a lot of writers, they don’t know that they put up guards at first. Maybe they’re trying to impress you. I throw all that away, and I get to who that person is. So sometimes I won’t even have them tell me the show; I’ll just ask them about their life and what’s going on with them. And now I’m maybe interested in this person and what they’re bringing, like, “That point of view needs to be on TV or could be a show.”

Are you a good boss, and do you think people who’ve worked with you would agree with your answer?

I have a reputation for being a good boss. Whether I’m an effective boss all the time — who knows? But I try to be fair. I hire people already believing in what they can do, so I don’t demand it. I just expect it, which is different. My job isn’t to pump you up to do your best, because I think you’re the best already.

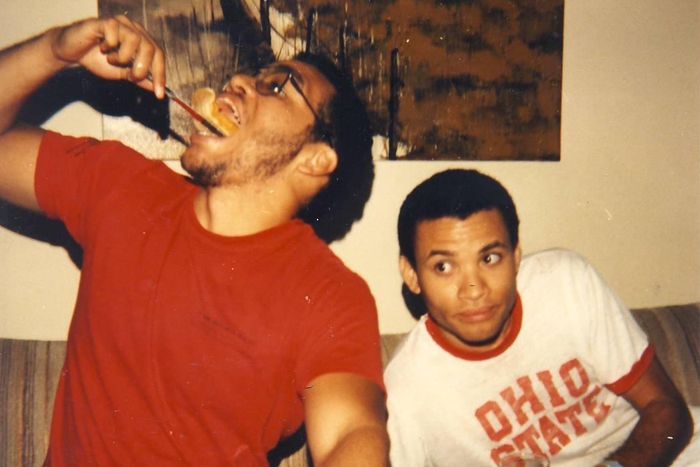

I want to talk a little about your younger brother, Marc, who also became a TV writer and who died from COVID last year. What was your dynamic with him like?

I love my brother tremendously. Miss him a lot. When I started doing stand-up, Marc started doing it about a year later and it surprised me. And I said, “Oh, you want to do stand-up?” He was like, “If you couldn’t do it well, then I wasn’t going to do it.” He wanted to see if I would sink or swim. And when I was able to swim, it gave him the confidence to do it.

He got in his own way, unfortunately. He was a very emotional person. He was very hard on himself. Low self-esteem, big ego, and high IQ in terms of abilities. But low IQ in terms of the worth of that. Crazy. He was a person who had many gifts but thought he wasn’t any good but also had the ego of someone who was good.

Writers face impostor syndrome, but he took it harder than he should have, and it was always his burden. I hated that he had that. But Marc was very inventive. He was very funny. We both had these different skill sets. I was a good impressionist. I could do the voices of different people. But Marc could do faces. He could just become somebody. It was the funniest thing to watch him contort his face.

Do you think his being like that stemmed from household dynamics when you were kids?

I’m convinced people are who they are. And part of your life’s journey is you have to get into the proper relationship with it. Marc was always like that. He always got angry faster. To me, I always compartmentalize, even when I look back at my childhood. There are things that my brain won’t allow me to remember. But Marc internalized a lot of that.

And you ended up working together early on.

On In Living Color. Purely an accident. I think Marc felt in my shadow sometimes, like he was just Larry’s brother. It would sting him. But he didn’t know that sometimes people call me Marc. He used to write jokes for George Wallace, sometimes for 50 bucks a joke. I walked to the Laugh Factory one night, and Wallace was there, and he said, “Hey, I forgot to pay you for that joke. I’m giving you $50,” thinking I’m Marc. And I’m like, “I’m just letting this guy give me his money. I’m not going to say anything.” Because I’ve known George for years. How dare he think I was Marc? And so then George calls me, and he is trying to get his money back and trying to give it to Marc. I’m like, “George, you pay me $50, I am keeping that.”

We used to joke about that for years.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’