Madonna canonized the concept of eras long before the internet made it a pop cliché. “I don’t want to just keep doing the same thing and saying the same thing,” she told MTV’s Kurt Loder in 1991. As inspired by classic Hollywood glamor as she was by pop’s pioneers, she turned shapeshifting into a business model, and future stars were taking notes. Thanks in part to a music press that still favored hard-edged rock gods, Madonna had to show she was more than the helium voice she’d first affected on earlier singles like “Borderline” and “Material Girl.” She proved it over the years, dipping into new jack swing, funk, hip-hop, trip-hop, flamenco, house, and musical theater. Madonna’s critics called her a vampire, but really she’s a collagist with a keen perception of how to make familiar imagery her own. She had Donna Summer’s sensual sparkle, Debbie Harry’s edgy charisma, David Bowie’s theatricality, and Andy Warhol’s infatuation with fame. Caryn James synthesized it succinctly in a 1992 New York Times story: “She is not a singer or an actress or a writer or a model but a performance artist, and every word she utters is part of the act.”

Of course, anyone that famous and that rich for that long is destined to lose some of their foresight over time. Still, Madonna remains history’s most influential pop star for a reason, a long-lasting legacy she is now revisiting on the Celebration tour. For someone who has refused to become a nostalgia act, this is the first time Madonna has built a roadshow around her 41 years of fame — and this list is an attempt to categorize it all: the greatest hits, eras, personas, and traits that have made her her.

.

The Dance-Floor Ringmaster

HIGH: “Vogue”

LOW: MDNA

This is the quintessential Madonna, the one who stoked disco’s dying embers in 1982 when she handed a Danceteria DJ a demo of what would become her debut single, “Everybody.” Its whirring funk synths were a mission statement, and she’d soon advance the song’s central command — “Let the music take control / Find a groove and let yourself go” — in a progression of bigger hits that treated the dance floor as a hub for escapism: “Into the Groove,” “Vogue,” “Music,” “Celebration,” “Girl Gone Wild,” and the polarizing “Bitch I’m Madonna,” which isn’t quite as self-aggrandizing as its title implies. In a broader sense, Madonna was making electronic dance music long before the acronym EDM became shorthand for rave culture. She helped further mainstream the upbeat dance music Black and queer musicians had been forging at a time when radio was still fairly segregated. (Her record label excluded her face from the “Everybody” artwork because executives weren’t sure whether Madonna’s sound would attract white or Black audiences.)

Though dance-pop provided a natural launchpad, it was never a fail-safe route: The “Disco sucks!” crusade of the late ’70s put the genre on shaky terrain. But the Madonna who spent her teens and early 20s in conservatories wasn’t about to discard her training. An anecdote she has repeated through the years is her decision to move to New York City (after ditching a University of Michigan dance scholarship) with “nothing but $35 and a pair of dance shoes.” She was first and foremost a modern dancer who studied the expressive, torso-centric Martha Graham technique. And though her sound upcycled disco, her ambiance was pure punk. Look at the fishnets, those rubber bangles, the mismatched earrings, that tousled hair — Madonna was timely, and she remained so for years. Because she had so much style, her relentless work ethic seemed effortless. Without her determination, dance-pop very well could have been subsumed by glam metal, adult contemporary, and other ’80s trends.

In the years since “Everybody,” she has frequently revisited and revised the genre, meeting the form where it is at any given moment. Even as a tony uptowner, Madonna has returned to the downtown Manhattan scene that birthed her, like when she threw a “pajama party” at Webster Hall in 1995 or promoted the ABBA-sampling Confessions on a Dance Floor at MisShapes, the 2000s’ hippest hangout. That particular album was a savvy crowd-pleaser that redeemed Madonna’s youthful appeal. The folksy post-9/11 introspection of her previous release, American Life, didn’t lead to much radio play, whereas Confessions was a sonic explosion that felt like the ‘80s and 2000s rolled into one exuberant, imperative night at the club.

Several years later, MDNA intensified her connection to EDM, but Madonna’s version sounded artificial compared to the highs of Daft Punk, Tiësto, or even her own electronically rousing Ray of Light. On 2019’s Madame X, a grab bag of world influences spanning Portuguese fado, reggaeton, and West African batuque, she sprinkled in the house highlight “I Don’t Search I Find,” which acts as a continuum, liking the clicky pulse of “Vogue” to the ’90s trance of Erotica and the refurbished disco of Confessions.

.

The Sex Provocateur

HIGH: “Justify My Love”

LOW: The “S.E.X.” lyric “Golden shower, latex thong, licorice whip, strap it on”

Madonna sings about romance as much as she does sex, but a yearning ballad like 1985’s “Crazy for You” was destined to be a footnote by the time “Justify My Love” came around. It’s still astonishing that the 1990 avant-garde ode to carnal fantasy (key lyric: “Poor is the man whose pleasures depend on the permission of another”) reached No. 1 on the Hot 100. MTV banning the video — in which Madonna slinks through a seedy Paris hotel filled with crossdressers, dominatrixes, and pansexuals in the throes of pleasure — was the best thing to happen to it. (She released it on VHS instead, leading to record-breaking sales.) “Why is it that people are willing to go and watch a movie about someone getting blown to bits for no reason at all, and nobody wants to see two girls kissing and two men snuggling?” she asked in response to the objections, an airtight defense that carried extra weight thanks to her headstrong support for gay rights at a time when most public figures wouldn’t dare. No one had learned much of anything by 2003 when the relatively tame smooches she planted on Britney Spears’s and Christina Aguilera’s lips at the VMAs provoked similar pearl-clutching.

By then, Madonna’s supposed sexual transgressions had long threatened to eclipse her music. So it goes for someone whose first major TV appearance involved pantomiming masturbation in a wedding dress and who more or less shrugged when Playboy and Penthouse published nude photos without her permission. (“I’m not ashamed,” she blared on the cover of the New York Post. Years later, Madonna told Rolling Stone it was “the first time I was aware of saying ‘fuck you’ with my attitude.”) Madonna learned early on that she could agitate the conservative squall of the Reagan-Bush era by dialing up her libido. She made an art out of it, even if no one wanted to call it that. The “Express Yourself” video blended feminist empowerment with sadomasochism, Truth or Dare showed a mama bear teaching her staff how to give good head, and “Human Nature” proffered a career thesis in the form of a taunt: “I’m not your bitch, don’t hang your shit on me.” Her soft-core Sex book, which caused hard-core hysteria in 1992, remains unmatched in terms of pop innovation, even if Steven Meisel’s photographs are more polished than most realized. People freaked simply because it was Madonna, the master of making headlines.

But provocation could be a burden. Shocking the public is Madonna’s high; she can’t go too long without a fix. So she recorded the Rebel Heart track “S.E.X.,” an overwrought “lesson in sexology” that’s more silly than edgy; thrust her tongue down a seemingly unexpectant Drake’s throat at Coachella in 2015; and posted bare shots on Instagram and mooned MTV. The curse of the digital age means that nothing anyone does is novel anymore, making it doubly hard to be judicious when you’ve made controversy your identity. Madonna was literalizing the ground she covered far more artfully 30 years ago. There’s power in seeing a woman in her 60s maintain her audacity, but repeating past exploits has a cringe factor that’s impossible to ignore. You have to hand it to her, though: The last thing she’ll ever be is boring.

.

The Catholic Iconoclast

HIGH: “Like a Prayer”

LOW: The “Holy Water” lyric “Yeezus loves my pussy best”

Never has a Met Gala theme fit someone better than 2018’s “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” fit Madonna. It’s right there in her name. To the Catholic church, she’s the embodiment of blasphemy. Religious leaders, including Pope John Paul II, condemned her for burning crosses and kissing a Black saint in the “Like a Prayer” video, and again for using Catholic symbols on the influential Blond Ambition tour (JPII called that one “satanic”), and again for crucifying herself during “Live to Tell” on the Confessions tour. The American Family Association, a right-wing fundamentalist organization, denounced the imagery in “Like a Prayer” and called on Pepsi to drop her $5 million endorsement deal. (The soda company did sever ties, but joke’s on them: Madonna had already cashed the check.) Madonna has always treated Catholicism as a prop, amplifying the theatricality of its pomp and circumstance. She started “Girl Gone Wild,” a 2012 jam about dance-floor lust that contains the lyric, “I feel like sinning,” by reciting redemption-seeking Christian liturgy known as the Act of Contrition. On 2015’s Rebel Heart tour, she performed “Holy Water,” a fusion of vaginal innuendoes and religious ecstasy as a pole-dancing nun at the Last Supper. Earlier this year, she emulated the Virgin Mary on the decadent cover of Vanity Fair’s European editions.

“Once you’re a Catholic, you’re always a Catholic,” Madonna told Rolling Stone in 1989 as a way of clarifying a fixation that has lingered since childhood. Maybe that explains why people were suspicious when she became the celebrity face of Kabbalah in the late ’90s — or maybe it was because by that point everything Madonna did drew a degree of mistrust. Regardless, her high-profile immersion in Jewish mysticism (more on that later) suited her better than the New Testament ever did. She has also disavowed religion altogether (“I’m not a Christian, and I’m not a Jew,” she rapped in “American Life”), which makes the most sense of all. From the beginning, Madonna saw religious symbols for what they were: ornamentation.

.

The Glamour Queen

HIGH: The 1991 Oscars

LOW: Recreating photos taken of Marilyn Monroe’s death

Madonna’s hair color may change — jet black, auburn, hot pink — but she is forever a blonde bombshell. Even when her natural brunette roots are showing, as they frequently did during her ’80s club-urchin look, those dazzling golden locks always register. She went platinum on the cover of 1986’s True Blue and in the videos for “Papa Don’t Preach” and “Express Yourself” later that decade. Call it a coming-out: The working-class girl from Bay City, Michigan, was now a wealthy dignitary boasting one of the world’s most recognizable silhouettes. As she steadily shed her streetwear, Madonna’s self-styling evoked Hollywood’s grande dames, the ultimate symbol of American aspiration. Like them, her moneyed perfectionism delighted and disgusted the public in equal measure. The goal was to be the most popular, the most alluring, forever on top.

When Anna Wintour put her on the cover of Vogue in 1989 to “show the range where fashion comes from,” it was the supermodel-gripped magazine’s way of declaring that celebrities were the future. The song of the same name gave Madonna’s glamor historical context, and yet its glossy allegiance to Old Hollywood was discerningly contemporary.

Madonna’s refinement peaked when she showed up at the 1991 Oscars wearing a pearl-coated Bob Mackie gown in the style of Monroe, $20 million worth of diamonds, and a fur shawl. She and her date — Michael Jackson, no less — had front-row seats. That night’s hyperfemme performance of “Sooner or Later,” the jazz carol Stephen Sondheim wrote for Dick Tracy, remains one of Madonna’s finest moments. She belted that number, striding the stage in front of a pink velvet curtain like she’d been there every night of her life. It was perfectly Madonna: She turned a song that sounds like the ’30s into a low-necked ’90s seduction.

That same essence made her a fashion magnet. Whatever mood she sought to convey was right there in the clothes, the hair, and the corresponding attitude. She has collaborated with Jean Paul Gaultier, Dolce & Gabbana, Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs, Stella McCartney, and Jeremy Scott. Madonna and the Versace clan were so close that she was one of the first people Donatella called when her brother Gianni was murdered in 1997. Madonna has a model’s grasp of the camera and a photographer’s grasp of iconography. She understood self-portraiture before everyone understood self-portraiture. That aptitude can lead even the sharpest vanguard astray, though. Again channeling Monroe in a 2021 V magazine spread — this time by recreating the infamous images from the night she died, down to Monroe’s naked body on her bed and the pill bottles on her nightstand — toes an uncomfortable line between homage and exploitation.

.

The Earth Mother

HIGH: Ray of Light

LOW: The NFT series in which plants sprouted from her vagina

The most shocking Madonna may be the one who doesn’t aim to shock at all. Earth Mother Madonna doesn’t flaunt her wealth, at least not as loudly. She’s more devoted to spiritual seeking than to crotch-grabbing. She sings about not being a material girl. She’s the people’s queen, elegant and attuned to fame’s impression. Like Eva Perón.

Evita, released in 1996, demanded the high-brow respect that often eluded Madonna. She was playing a long-gestating, Broadway-caliber role that Barbra Streisand, Liza Minnelli, Bette Midler, Meryl Streep, and Michelle Pfeiffer had circled. The mere idea of dismissing those powerhouses to cast Madonna, whose track record in movies was spotty at best, enraged musical purists. But it was a divine 180 from Sex, and Madonna understood the weight of Perón’s political imprint better than anyone.

Madonna found out she was pregnant while shooting Evita. “Some people have suggested that I have done this for shock value,” she wrote in a diary during the movie’s production, subsequently published in Vanity Fair. Much to the contrary, motherhood suited her, giving her the creative wellspring that conjured her most acclaimed album, Ray of Light, an atmospheric meditation on fame, love, spirituality, and her parental renaissance. Alongside her next two albums — Music and the grossly underrated American Life, all of which dipped into mature electro-folk — Ray of Life was an expert complement to Madonna’s newfound Kabbalah studies. Unlike the Christian crosses she’d brandished in the ’80s, her much-mocked red bracelet wasn’t just for show. The metaphysical teachings she absorbed as the overblown celebrity face of Kabbalah were reflected in the earthier lyrics Madonna co-wrote in the late ’90s and early 2000s. Plus, she made yoga cool. As for phony British accents? Debatable.

Earth mother Madonna is also more political. “I feel a sense of responsibility because my consciousness has been raised,” she told SPIN in 1998. Though she’d been outspoken about AIDS and gender equality, Madonna was now a war critic, a climate-change activist, and an international humanitarian. In 2006, she co-founded Raising Malawi, an organization that has built schools and a children’s hospital in the African nation. She now has six children, four of whom were (somewhat controversially) adopted there.

Perhaps her most rebellious act as Earth mother is not letting it dull her sharper edges as she ages. She has remained, most crucially, a dance-pop disciple and a sexual rabble-rouser. But even her most innocuous persona can get messy. Madonna’s entry into the nebulous world of NFTs yielded a 2022 video series called “Mother of Creation.” A collaboration with digital animator Beeple, the three clips depicted her cartoon avatar giving birth to a tree and butterflies, linking nature to spirituality through a dubious slice of capitalism. They sold for a few hundred thousand dollars apiece, signaling that multimillion-dollar NFT sums had already flamed out.

.

The Business Maven

HIGH: Starting her own record label

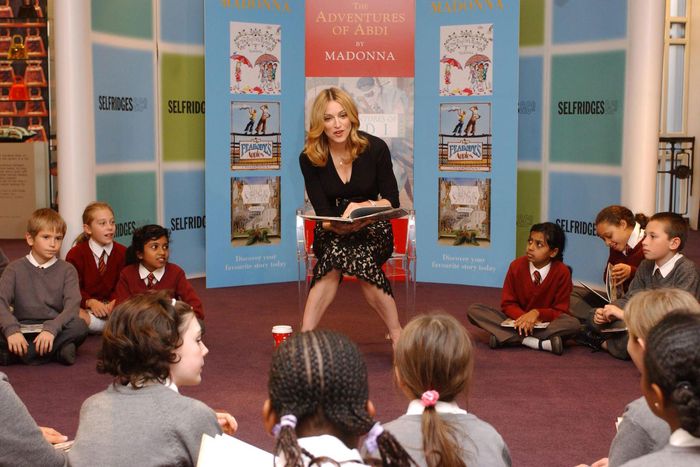

LOW: Her children’s book series

Surprise, surprise: One of Madonna’s skills is also a source of scorn. Those who begrudge her say her only talent lies in self-marketing, a claim as trite as the notion that Marilyn Monroe had nothing to offer but curves. Rock stars aren’t supposed to show their work, but Madonna never hid her go-getting nerve. She turned up at Sire Records co-founder Seymour Stein’s hospital bed so he’d sign her first record deal. Almost immediately, she was an emblem of the moment. Call it business acumen, call it artistic ingenuity, call it luck. Madonna understood before almost anyone else how music videos, fashion, and media attention perpetuated pop stardom.

If tabloid scrutiny bothered her, she seldom let on — all press is good press. At her 1985 wedding to Sean Penn, the spectacle was the point. The event brimmed with celebrities, drawing paparazzi choppers determined to capture the outdoor Malibu nuptials. If megafame means surrendering to the whims of the masses, Madonna maintained control by refusing to be some A&R puppet, a conviction that now earns Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and Lady Gaga routine praise. In 1992, she inked a $60 million partnership with Time Warner to start her own label, Maverick Records, which signed Alanis Morissette, the Prodigy, Deftones, Muse, and Michelle Branch. In 2007, Live Nation gave her a pacesetting $120 million promotional deal.

Madonna’s enterprise has also spawned unimaginative children’s books (a departure that only made sense in the context of her elite Anglophilia), a skin-care brand, fitness centers, clothing lines for H&M and Macy’s, and the intermittently relevant streaming service Tidal. In 2015, she promoted Rebel Heart at Sotheby’s, where she gave interviews in front of her multimillion-dollar art collection that included originals by her late pals Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat (an old flame), and Warhol.

Madonna’s trick was to never separate creativity from business. “What I do is total commercialism, but it’s also art,” she said in 1989. “I like the challenge of doing both.” You can hear that marriage in the music, in the way she bends herself to convey an idea worth selling. According to Nile Rodgers’s memoir, when he first mixed “Material Girl,” he suggested transposing it into a key that avoided the nasally wail he heard in her voice. Madonna protested. She saw the girlishness she’d adopted as an ironic comment on Reagan-era consumerism, and who better to confuse the world with such messages than a capitalistic superstar?

.

The Wannabe Movie Star

HIGH: Desperately Seeking Susan

LOW: Swept Away

“I’ve been a failure so far,” Madonna said in 1991, showing uncommon humility when discussing her Hollywood pursuits. She credited her lambasted acting to a lack of foresight: “I haven’t honored or respected a movie career the way I should have. I didn’t approach it the way I approached my music career. I’d had a lot of success in music, and all of a sudden people were going, ‘Here’s a movie.’ And I didn’t think about it. I just took it.”

The back-to-back ’80s flops Shanghai Surprise and Who’s That Girl had polluted the promise of 1985’s Desperately Seeking Susan, a crafty screwball comedy in which Madonna plays a streetwise New Yorker who longs to be at the center of everything. No wonder the role fit her. Dick Tracy won back some favor in 1990, and Madonna then linked up with distinguished directors like Woody Allen, Penny Marshall, Abel Ferrara, and Spike Lee. But even a Golden Globe win for 1996’s Evita couldn’t sweeten the stench of Madonna’s weakest performances. For every Desperately Seeking Susan or A League of Their Own, there was Body of Evidence, The Next Best Thing, or — God help us — Swept Away, directed by then-husband Guy Ritchie in a stilted attempt to update a European art-house classic. (There’s also a score of missed opportunities. At one point, she was developing a biopic about Martha Graham. She was attached to play Velma Kelly opposite Goldie Hawn in Chicago, a role she seems made for. Most intriguingly, she and Agnès Varda talked about doing an American remake of the great Cléo From 5 to 7. “She’s a natural-born actress,” Varda said.)

Many pop stars (most, arguably) aren’t meant to be actors. Or directors. But Madonna can be counted on to drop references to Fellini, Visconti, and other cerebral auteurs. She saw music as its own form of acting, both in the studio and in front of the camera. Videos were a “chance to make little movies.” And yet her dedication to cinema didn’t translate to a thriving film reputation. Her performances tend to feel distant and manicured. She rarely figured out how to relinquish herself to another master, which explains Madonna’s recent ill-fated decision to direct her own biopic.

Madonna’s brush with Hollywood isn’t exclusive to the big screen, though. Her videos, tours, and photo shoots are indebted to the movies she admires: Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in “Material Girl”; Cabaret in “Open Your Heart”; Metropolis in “Express Yourself”; Bay of Angels in “Justify My Love”; Looking for Mr. Goodbar in “Bad Girl”; Marlene Dietrich on the Girlie Show tour; Koyaanisqatsi in “Ray of Light”; Humoresque in “The Power of Good-Bye”; Mae West in “Hollywood”; Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! in “Girl Gone Wild”; Marylin Monroe in the pages of Vanity Fair and V. She has a Hollywood perspective, whether or not Hollywood has known what to do with her.

.

The Late-Career Trend Chaser

HIGH: “Bitch I’m Madonna”

LOW: Those grills

Madonna was long thought to be pop’s bellweather, someone who sensed what was happening in culture and lept a step ahead. Whether working with big-name producers (Nile Rodgers, Babyface, Diplo) or plucking future hitmakers from relative obscurity (William Orbit, Stuart Price), Madonna made sounds distinctively hers. But something shifted in 2008. Hard Candy was the first album of her then-25-year career that could have been recorded by any number of her peers. Inspired by Justin Timberlake’s FutureSex/LoveSounds, Madonna recruited Timbaland, Pharrell Williams, and Danja, who came up with the same beats they would have given Nelly Furtado, Britney Spears, or Timberlake. Gone was the evocative delivery that made Madonna singular, replaced by overproduced soullessness.

Her next album, 2012’s MDNA, was even less distinct, an EDM-lite trifle whose lead single featured Nicki Minaj and M.I.A. chanting “L-U-V Madonna.” (As it happens, M.I.A. pulled off the rare feat of upstaging Madonna, dwarfing an otherwise incredible Super Bowl halftime performance with her middle finger.) The MDNA misstep came at a crucial moment. Madonna was in her mid-50s, the social-media age had taken over, and she’d already far exceeded the half-life of most pop careers. Someone who spent so long reinventing herself was now stuck in the shadow of younger, buzzier upstarts. That became glaringly transparent when Instagram drained celebrity culture of its mystique in the 2010s. Her presence there, and on TikTok, can be described, generously, as kooky.

Around the time Madonna joined Instagram, she introduced her fishiest fashion accessory: diamond-encrusted grills, a step in the wrong direction as far as multicultural homage is concerned. She posted rambling captions and went a little too hard on frivolous filters. Her wit and intelligence butted up against what could be perceived as childishness. Calling Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” “reductive” on Good Morning America would have better suited the ’90s, when pop icons routinely trashed one another in the press, than 2012. Her next two albums, 2015’s Rebel Heart and 2019’s Madame X, were mixed bags, stuffed with too many producers and not enough cohesion. They failed to produce the hit singles she’s known for (“Bitch I’m Madonna” excepted, sort of). By the time she was recording a gratuitous “Hung Up” remix with Tokischa and making out with her onstage, Madonna came off less like a renegade and more like a wayward attention seeker — a fatal flaw for someone whose grandstanding always seemed purposeful.

Still, glimmers of “the old Madonna” emerge. Her concerts in particular remain acrobatic parades. “There’s no other performer like her,” The Guardian raved when the Rebel Heart tour launched. The Celebration tour, Variety wrote over the weekend, “[lays] on spectacle after spectacle and show-stopper after show-stopper,” replete with biblical references, carnal punch, and political cries.

Today, Madonna casts herself as the underdog, vilified by a misogynistic world that rarely understands her sense of humor. If her younger counterparts don’t face quite the same scrutiny, it’s in part because Madonna propped herself up as everyone’s punching bag and refused to delate. As she declared in 2016, “I think the most controversial thing I’ve done is to stick around.”