This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

When Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah was in high school and college, he worked at a clothing store in the Palisades Center mall in West Nyack, where he spent his lunches and time between shifts at the Barnes & Noble upstairs — reading half a story, going back to work, then returning on his next break with the words still alive in his head. There were the literary magazines he discovered on the racks, like Ploughshares and The Paris Review. Wells Tower’s surreal, tough short-story collection, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned. On one break, he read Kahlil Gibran, whose poem “On Houses,” from the 1923 collection The Prophet, arrived with its description of dream-filled bodies and comfort-filled homes as an invitation to engage; a few years before, his mom had lost her job as a kindergarten teacher and the bank foreclosed on their house in nearby Spring Valley.

Adjei-Brenyah fueled these private study sessions with McGriddles and sweet teas from the food-court McDonald’s, sustenance that made him break out and feel awful but was cheap and caloric. He worried he might never stop working at the mall. But now, Adjei-Brenyah is 32 and about to publish his second book and first novel, Chain-Gang All-Stars. On a Saturday at the Palisades Center this spring, he finds it looks much the same as it did when he was growing up: The Barnes & Noble is still here with its mural of writers from the western canon drinking coffee. The clothing store he worked at is, too, with a DJ in the entry spinning Rihanna. Then we pass what looks like a shooting range — for kids. Adjei-Brenyah stops. “What is this?” he asks. “A shooting thing? Like, with BB guns?” I say I think that’s right, and he keeps staring at it. “Malls!” he says theatrically. “They’re shooting things here! What is this?” (It turned out to be a virtual shooting range. Even so.)

The book that vaulted Adjei-Brenyah onto the best-seller list and earned him critical accolades and film options and changed his life was his first one, the story collection Friday Black, from 2018. Organized into perfectly wild, perfectly neat episodes, it takes an irreverent, genre-bending approach to ripped-from-the-headlines subject matter. In “Zimmer Land,” white patrons go to a theme park to shoot at mostly Black and Muslim employees who are strapped into padded suits filled with fake blood. The title story — to which Universal bought the film rights — is set at a mall like this. In it, a frenetic sale leaves dead bodies behind to be swept up casually by employees, a nod to an actual death Adjei-Brenyah heard about at Palisades. (A girl had fallen from the top floor; her body was covered with a tarp.) In “The Finkelstein Five,” a white man kills a group of Black children with a chain saw. “Is it hyperbole? I don’t know,” Adjei-Brenyah told one interviewer. “When you kill someone with a gun or a chain saw, they’re just as dead either way. When I say ‘chain saw,’ you have to pay attention.”

Out May 2, Chain-Gang All-Stars — which the author says he started as a story for Friday Black but “overshot by a couple zillion words” — is also set in an America a few degrees off from reality, where the for-profit prison system and a love of violent sports have produced an inevitability: Prisoners can choose to compete in gladiatorial, to-the-death, televised battles to win their freedom. They do so inside alliances called Chain Gangs, whose members never fight one another and which offer the possibility for something like solidarity when they’re not fractured by hierarchies and subterfuge. The prismatic, bloody story follows two Black women, Loretta Thurwar and Hamara Stacker, lovers and superlative fighters and leaders, often through the eyes of orbiting characters: superfans, fellow prisoners, anti-prison activists, sleazy TV hosts, even sentient-seeming hovering cameras. The Hunger Games–like plot finds depth in a nuanced matrix of race, sex, and gender politics.

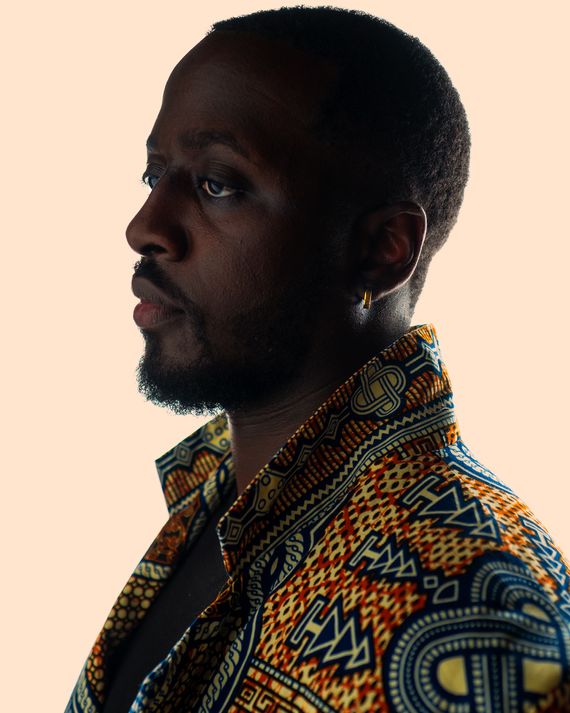

Adjei-Brenyah is tall and handsome, doe-eyed, with an easy smile. He has a serene exterior and a palpable interior churn like the heat off a whirring computer. His speech is dense and quick, funny and slightly mournful, and laced with the references of a mall-grown, M.F.A.-honed, basketball-and-anime-obsessed first-generation New Yorker. The novelist Dana Spiotta, one of Adjei-Brenyah’s professors at Syracuse University, where he earned his graduate degree, likens Chain-Gang to an old-fashioned “social novel” tackling “the carceral state and prison abolition — but he’s mixed it in with Marvel, a comics universe, and all the things that make Nana so particular.”

At the time Friday Black came out, Adjei-Brenyah had been on a plane twice in his adult life. Suddenly, he was flying around the world, juggling “all these fancy dinners and shit,” as his friend the sound engineer Mike Mitch puts it in a rap video called “Ellison” — after Ralph — that the two released last year. When Adjei-Brenyah sold his stories’ film rights, he made more money than he’d thought he ever would. But something else changed too. “The illusion that happiness was on the other side of some specific achievement was shattered,” he says. “I had to, like, figure out who I was besides someone striving to be a ‘real author.’”

Writing used to be entangled with desperation and magical thinking. He was at it seriously by 16. He joined his high school’s lit mag, turning out work in a genre he describes as “I’m sad but secretly.” One poem, “The Diamond Rose,” described a flower encased in diamond like an insect in amber: “It’s dying on the inside, but it looks pristine.” His peers cheered these early efforts, maudlin as they were. “I remember the feeling of seeing people react to my shit. And being like, Damn, I like that feeling.” Spring Valley, in Rockland County, is a downbeat kind of place, a former manufacturing center with a feeling of better days behind it. Adjei-Brenyah’s parents, Ghanaian immigrants, landed there with their three kids, of whom Nana was the second. He calls himself a good student, if not crazy good like his sisters, both academic stars. (When we run into a friend of his elder sister’s at the mall, she tells me, “The whole family is brilliant.”) He took his extracurricular obsessions seriously: first basketball, then writing because, he says, it “was free, and you couldn’t easily steal it from me or take it from me like you could with, like, electricity.” Unlike basketball, where you were either going to try for the NBA or you weren’t, in writing, “there was no wall.”

He was around 13 when his mom lost her full-time teaching job, and they eventually moved into a series of dispiriting apartments. Between school and the mall, Adjei-Brenyah wrote intensely, even when the lights kept going out. An eviction sent the family into a basement unit that flooded regularly. His parents had once seemed secure, with his dad working as a criminal-defense attorney. Now both were struggling with their mental health, and the family was eating out of a bare kitchen, cooking off a series of hot plates they had to keep replacing. “You could just get another hot plate. Another hot plate. That was the thing,” he says.

When he finished high school and enrolled at SUNY Albany, he felt slightly ashamed — his elder sister had won a partial scholarship to Columbia. But Albany proved to be an oasis. Through a university mentorship program, he was paired with Lynne Tillman, the novelist and essayist. Tillman recalls “this very tall, very beautiful, very, very thin young man” showing up at her office seeming nervous. “At a certain point, he said with tremendous genuineness, ‘I want to be a writer.’ I said, ‘Well, what books have you read?’” She remembers he looked “a bit abashed.” She started him on a brisk regimen to manage between classes: Edith Wharton, Henry James, James Baldwin, Grace Paley. One week, she gave him George Saunders’s 1998 story “Sea Oak,” about a family in a broken-down apartment haunted by a dead aunt, a woman who accepted indignity in life without much complaint. The woman returns to counsel her nephew, an employee at a Hooters-esque joint where men are the servers, and advises him to show off his penis to make his way up a twisted ladder. Something clicked.

“I’m like, This is literary shit going on here,” Adjei-Brenyah says. He saw a main character caught in a slantwise yet familiar world “trying to decide what to do and why some people suffer.” Plus there was that bleak apartment. It inflamed a bit of “mad, mystical thinking”: He would pull material from his experiences and become successful enough at writing “to fix my mom and dad’s life.” His reverence for Saunders took him to the M.F.A. program at Syracuse, where the writer teaches. Adjei-Brenyah was the sole person of color in his small fiction workshop, but he got access to a sense of lineage. His writing teacher Arthur Flowers had been taught by the writer and civil-rights activist John Oliver Killens, who learned from Langston Hughes. “Things My Mother Said,” the second story in Friday Black, came from a Flowers prompt to write a story to change the world. (Adjei-Brenyah misheard the prompt as “save the world.”) He studied Ishmael Reed. He developed bonds with Spiotta and Saunders that extended beyond the classroom.

He likens his time at Syracuse to a narrative time skip, “where the characters come back really strong. I had the true I’m going to go learn Rasengan, and I came back and I know how to do the Rasengan.” He stops, apologizing for the anime reference: “These are specific Naruto things.” (On Twitter, Adjei-Brenyah once mapped his writing teachers against Naruto characters: “Lynne Tillman = Iruka Sensei / Dana Spiotta = Kakashi / Arthur Flowers = Jiraiya / George Saunders = Killer Bee.”)

Within a year of graduating, he sold his first book. The fixation on changing his parents’ reality was the pressure he needed, he tells me, paraphrasing a quote from Giannis Antetokounmpo of the Milwaukee Bucks: “I’m not as talented as Steph Curry. I’m not as talented a basketball player as Kevin Durant. I’m just fucking desperate.”

With the advance, Adjei-Brenyah was able to move his parents into an above-ground apartment, but by then, his father had been diagnosed with cancer; as his health deteriorated, the steps leading up to the unit became hard for him to manage. “It was this really mean irony,” says Adjei-Brenyah. “One of those fucked-up genie-type things where you wished for this thing and then …” His father died six months after the book came out.

Adjei-Brenyah began to feel a loss of purpose. The desperation he had used to write Friday Black couldn’t sustain him. “Who are you beyond that? Okay, now your dad is dead, and also you were only thinking about the fact that you have no money,” he says. “It’s not enough to just get people to care. With the brief amount of time you have people’s ears, what’s the most important thing you have to say?”

His father’s time as a defense attorney had planted a seed: Adjei-Brenyah had become interested in prison abolition. Post-college, he had worked with the Rockland Coalition to End the New Jim Crow, an activist organization aiming to cease the racial oppression of the criminal-justice system. He’d read Michelle Alexander. Now he read the work of Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba. He wondered if writing about abolition could help him understand how he felt about it.

Chain-Gang All-Stars features footnotes, some fictional, some not. One cites the 13th Amendment, its caveat that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” shall exist within the United States “except as a punishment for crime.” The character Thurwar, with her Zen-like stillness, acts as the novel’s “middle C,” a “tuning fork” against which other characters “can be inflected.” He knew the protagonist had to be a Black woman: “I wanted someone who was right at the nexus of being loved and inherently hated and sexualized — both condescended to and revered. I feel like that’s more a woman’s experience in any power position than a man’s.” He cites the public treatment of Serena Williams versus that of LeBron James: “Both get a lot of complete fuckery bullshit,” but for Serena, he says, “it’s so different.”

After we leave the mall, he tells me, he’ll visit his mom in Spring Valley, then it’s back to his three-bedroom apartment in the Bronx. Adjei-Brenyah distinguishes between his “real friends” and “book friends,” between his “real world” and “book world.” He knows his real friends have watched his fortunes change — not that they seem fazed. He’s still getting used to the fact that he belongs in book world too. One thing he’s noticed: When he was growing up, people in his hometown would say his name wrong. He performs it for me, Na-na, nasal like a kid making fun of you. In book world, though, moderators make extra sure they say it right: Nah-nah. The fact that they take the time — the fact that, unlike Friday Black, he knows no one’s sleeping on the new book — “feels a lot less comfortable. I’m so used to the wrong pronunciation. I’m so used to being on the outside, looking in.” Now his mispronounced name can be a comfort. “I feel endeared to it,” he says. “It lets me know where you know me from.”