This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Don Hahn remembers the night he lost the Oscar for Best Picture. The Beauty and the Beast producer sat in the seventh row of the 64th Academy Awards, next to Jeffrey Katzenberg and behind Sylvester Stallone, listening as Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman announced the winner. It was 1992, and the film’s nomination was historic — a first for animation — but another thought raced through Hahn’s head. Before the ceremony, Disney CEO Michael Eisner had called with an unusual request.

“If you win, could you do the following?” Eisner asked him. “Could you say, ‘Thanks, everybody that worked on the film — and now I’m going to Disneyland’?” Eisner assured Hahn that the company would send a donation to the charity of his choice as thanks.

“Really, am I going to do this?” Hahn remembers thinking. To him, sitting at the Oscars was like being “at the United Nations, because everyone comes from around the world to celebrate film.” But Eisner had understood that the event was prime real estate for product placement.

Hahn’s agita ended up being moot. Beauty and the Beast lost to The Silence of the Lambs. But Hahn never forgot the sentiment behind Eisner’s request: that even as they anticipated a landmark moment for the medium, Eisner was thinking less about the achievement than he was about commercial opportunities.

For years, Disney tried to get back on that stage with animated films that appealed to mass audiences, earned boatloads of cash, and re-established the company’s reputation, which had stagnated in the post-Walt era. “The executives really wanted to make these serious movies that would get them taken seriously by the Oscars,” says animation restorationist Garrett Gilchrist. “So you get Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.” Both films, despite their heavier subject matter — colonization, discrimination, religious zealotry — failed to drive Oscars attention in major categories.

Meanwhile, competition intensified. Pixar (not yet a Mouse subsidiary) made Toy Story. Warner Bros. made Space Jam. Erstwhile Disney dissident Don Bluth made Anastasia at 20th Century Fox (also not yet a Mouse subsidiary). And Katzenberg, who sat next to Hahn the night Beauty and the Beast lost, left for DreamWorks and poached Disney’s top animation talent. By the end of the ’90s, feature animation looked as cutthroat as the rest of Hollywood — but not at the Oscars. The films could squeak into the original-songs and scores categories, but Best Picture remained out of reach.

Then, in 2002, the medium was finally given its due. The Best Animated Feature category was the brainchild of Bill Littlejohn and June Foray, two longtime animation organizers and Academy governors who had been petitioning for years to recognize feature animation. (The Best Animated Short Film award dates back to the ’30s.) In the category’s first year, Shrek won, and for some, it felt like validation: “In the lobby of this building is the first Academy Award ever given for an animated movie in competition,” Katzenberg told the Los Angeles Times in 2003. “That’s a dream fulfilled for me.”

In the 20 years since, however, the realities of the category have divided animators. The award has overwhelmingly favored major U.S. studios with pockets deep enough to fund awards campaigns — specifically Disney or Disney-distributed films like those from Pixar. (Combined, the two studios have won the award 15 times in 21 years.) Best Animated Feature tends to go to kid-friendly films animated primarily in 3-D CGI (19 times). Independent films, movies aimed at adults, or those created in different art styles rarely get nominated, let alone win. The 17 animators interviewed for this story disagree on the award’s success in championing animation, question its history of nominees and winners, and wonder whether its issues are ultimately fixable.

“As an Academy member, I’m always frustrated,” says Jorge R. Gutierrez, who directed animated projects like The Book of Life and Maya and the Three. “I look at the animated-feature history of the Academy, and I go, Oh man, it’s kind of embarrassing.”

One thing all animators agree on is this: They never like hearing that their art form is just for kids. It’s common for them to find their work pigeonholed as a “genre” for children rather than a medium that encompasses myriad filmmaking techniques and infinite story possibilities. Guillermo del Toro, director of Netflix’s Pinocchio, has repeated the sentiment once, twice, several times over the years and echoed it in his awards campaign this year. Every animator interviewed for this story, regardless of their stance on the Best Animated Feature category, pointed to this misconception in some way. And the Oscars haven’t always been helpful in bridging the gap.

“The word that me and a lot of my colleagues use is ghettoization,” says Kirk Wise, director of Beauty and the Beast. He recalls that when that movie was up for Best Picture, “there were those in the awards broadcast who had to be snarky and pooh-poohed the notion of a ‘cartoon’ being included with ‘real movies.’”

He and many other animators feel that the creation of a separate Best Animated Feature award all but kneecapped animated films’ shot at competing for the top prize. “It creates a separation: adult table, kids’ table,” he says. Not everyone agrees that Best Picture is out of reach for animated films, including Wise’s Beauty and the Beast colleague Hahn and other Disney veterans, but it’s not likely. The only two animated films to crack the Best Picture lineup after Beauty and the Beast were Pixar’s Up and Toy Story 3 — the latter 12 years ago, and both only after the field expanded from five to 10 nominees.

Animators generally sense an elitism around how their work is presented onstage, though, compared to that of their live-action peers. At last year’s Oscars broadcast, three actors who play live-action versions of Disney princesses (characters that originated in animation) introduced the Best Animated Feature nominees by saying, “So many kids watch these movies over and over and over and over and over and over. I see some parents know exactly what we’re talking about.”

“That was a kick in the balls to the entire animation community,” says Gutierrez. “To be told, ‘Hey, you guys are making movies for kids, and parents are falling asleep: Thank you for making babysitter movies.’” Animators around the world published scathing responses on social media and, in a Variety op-ed, The Lego Movie directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller took the Academy to task for “the repeated diminishment” of their art form.

“Anybody who works in filmmaking — I feel they’re my peers,” says Sergio Pablos, director of 2019’s Klaus, which was nominated for Best Animated Feature but did not win. “I don’t think they look at me the same way.”

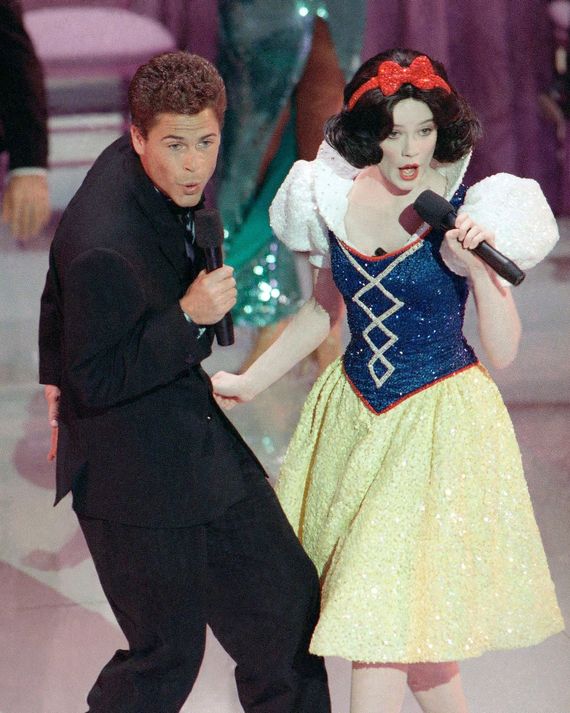

The condescension is part of a long tradition, says Hahn. “For some reason, when people hear the word animation — and this is not in reference to the Academy,” he says carefully, “they put their idiot hat on.” He points to the infamous 1989 telecast. “Let’s find the wackiest thing we can do, and we’ll have Rob Lowe dancing with Snow White.”

Within that context, some animators find it hard to take the award seriously or feel welcome among the Academy’s broader membership. Like with other Oscar categories, it’s often a popularity contest: Since 2017, nominees have been chosen by a group called the Animated Feature Committee, and before that the animation branch, but winners are decided on by the broader Academy voter base. The Animated Feature Committee is an opt-in nominating body open to members across the Academy and its size and make-up, which are not made public, shifts every year. Some animators worry that voters don’t actually watch the animated movies they vote on. “You’ve seen all those interviews,” Gutierrez says, referring to quotes from anonymized Academy members in The Hollywood Reporter. “It’s basically, ‘Whatever my kids watched, or whatever the most popular movie is, that’s what I’ll vote for.’”

Creators of independent and adult-oriented animation tend to take this personally and bring it up over and over again, pessimistic about their Oscars chances. “Your only question is Am I going to get to lose to Disney this year?” says Craig Staggs, co-founder of indie studio Minnow Mountain, which handled animation for the recent Richard Linklater film Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood. “Disney wins, and nobody pays attention to your film,” he says. “And Disney was going to get the attention anyway.”

Gutierrez, who has worked on several projects for major studios, agrees. He notes that four of the five films from Cartoon Saloon, an independent Irish studio known for its vibrant 2-D animation, have been nominated but never won. “Their business model is getting an Academy Award nomination. That helps promote their movies. I don’t think they ever assume they’ll win, because Disney or Pixar is going to win.”

“We felt we were in the running with Wolfwalkers, but it’s true — in most cases, the nomination is the prize,” says Cartoon Saloon co-founder Tomm Moore, who directed that 2020 nominee. He notes that “it’s not so much our business model as a nice bonus if it happens.”

“You don’t have to argue anymore that there’s a bias,” Staggs says. Though it is no longer the sole arbiter of the nominees, he sees the makeup of the Short Films and Feature Animation branch as one problem: “More people that have worked for Disney vote on these films through the Academy than any other company. And the second, I think, is DreamWorks, who have won the second most. So it’s a direct result of representation. It goes against the stated spirit of the awards.”

“Having been in those meetings, the old guard is very, very, very stubborn,” says Gutierrez. “A lot of the older Academy members are the ones that go to all the meetings, go to all the screenings, and they’re definitely the ones who vote — just like real politics.”

He cites a specific rule as a barrier to entry for new voters for Best Animated Feature. To be approved for membership in the branch, unless they have already been nominated for the animated-feature or short-films Oscar, animators must prove they have a number of production credits that meet the criteria. For example, in feature animation, “you have to have done two supervisor positions on a theatrical movie,” Gutierrez says — titles like director, production designer, or VFX supervisor. “For women and minorities, that is almost impossible historically. They keep going, ‘Hey, guys, can we invite more women and more minorities into the group?’ No one fulfills those requirements.”

That same old guard, Gutierrez says, isn’t always welcoming of the wide breadth of animation styles popular around the world. “When I went to film school in the ’90s, there was snobbery from the faculty around anime. We were told, ‘Don’t draw like that. Those movies are not good.’ In the industry, the same thing happened,” he says. Anime films, for example, are rarely nominated for Best Animated Feature — unless the movie is made by Studio Ghibli. “There’s a whole generation of Academy members who are now in their 70s and 60s and 50s — and I would dare say even their 40s — who just outright do not like anime. And they will not watch it,” he says. “It’s just insane to me.”

Other branch members point out, however, that the last two decades haven’t been a complete shutout. Films made by neither Disney nor Pixar have broken through and won the award six times. DreamWorks won the award once for Shrek, a film produced in house, and again for Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, a co-production with indie studio Aardman Animations. Seven anime films have been nominated for Best Animated Feature with one winner in 2003, Spirited Away, which Disney distributed in North America. In general, several other studios compete year after year, and seven of them have secured at least three nominations each:

- Studio Ghibli: Six nominations, one win for Spirited Away (which Disney distributed in North America)

- Aardman: Six nominations, one win for Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (which DreamWorks distributed in North America)

- Sony Pictures Animation: Four nominations, one win for Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

- Laika: Six nominations, zero wins

- Cartoon Saloon: Four nominations, zero wins

- Netflix Animation: Four nominations, two of them this year, zero wins; an additional three films distributed by Netflix but produced by outside studios have also been nominated

- Les Armateurs: Three nominations, zero wins

With that history in mind, Nancy Beiman, a veteran animator who has worked both independently and for Disney, doesn’t share the detractors’ view that the award or the animation branch are to blame for the complaints. “You’re talking to an older animator, and I absolutely love independent films and the foreign films. I prefer them to most of the major-studio products,” says Beiman, who is a member emeritus of the branch and no longer votes. The idea that an “old guard” of animation branch members is to blame for one studio or another’s success is ageist and unfair, she says. “All of the older governors, I believe, are no longer on the board, so they have their younger people. You don’t know how people think.”

The feature-animation market looks completely different today than it did when Best Animated Feature was introduced. In 2002, nine animated films were deemed eligible for competition. This year, there are 27 — from major studios, indies, and foreign markets.

“The award only became viable when there were enough features to make it a fair competition,” says Beiman. In her view, the category remains as equitable and fair as any other and even more competitive today, as new technology has facilitated the release of more animated films per year — “not all worthy of note,” she quips.

Animators agree, however, that the Best Animated Feature award is important. A film’s victory can spotlight an artist like Hayao Miyazaki for an international audience, as Spirited Away did, and it can catapult careers into new territory, which is why animators care that the awards are decided fairly and foster respect among their fellow filmmakers instead of creating a “cartoon ghetto.” The stakes are not theoretical, and both the Michael Eisners and Sergio Pabloses of the world know it.

“I agree with the nominations a lot more than I agree with the wins,” says Pablos. This year’s field includes two stop-motion titles (Marcel the Shell With Shoes On and Pinocchio) competing against the 3-D CGI fare (Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, The Sea Beast, and Turning Red). All of the nominees are family-friendly, but they use the medium to wrestle with themes like fascism, loneliness, puberty, war, and mortality. Not every animator interviewed cares to watch the Oscars, but all of them will take note of which film wins and whether the broadcast turns the affair into a cheap joke.

“We put as much hard work into our films as any live-action filmmaker, but unfortunately, that’s not how it’s perceived,” Pablos says. “As long as people consider animation to be something that is not quite filmmaking, whatever system we put in place is not going to be fair.”

Correction: This story originally stated that nominees are chosen by the animation branch. It has been updated to reflect rule changes since 2017.