Ask someone what prog rock is, and, after establishing that “prog is short for progressive” and, perhaps, that “prog is for nerds,” things get a little hazy. The genre is usually defined as the complex, composed classics from Genesis, Gong, or Emerson, Lake & Palmer. But it can be free-form too, like the psychedelia of the Mars Volta or the atonal concrete of King Crimson. If are looking to find its true essence, though, no one individual fits the description more than 75-year-old keyboardist and composer Rick Wakeman.

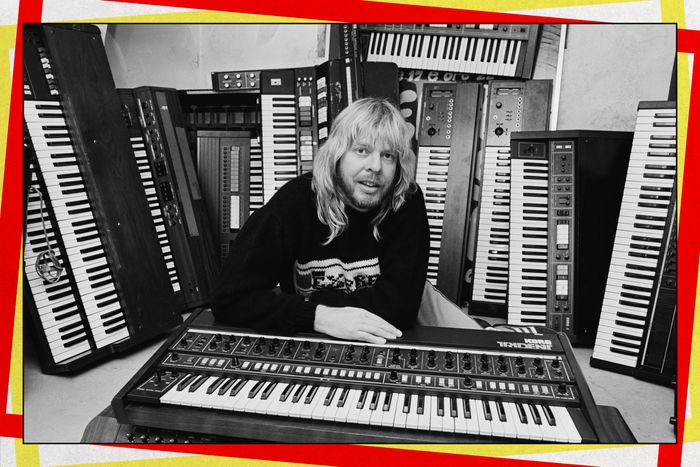

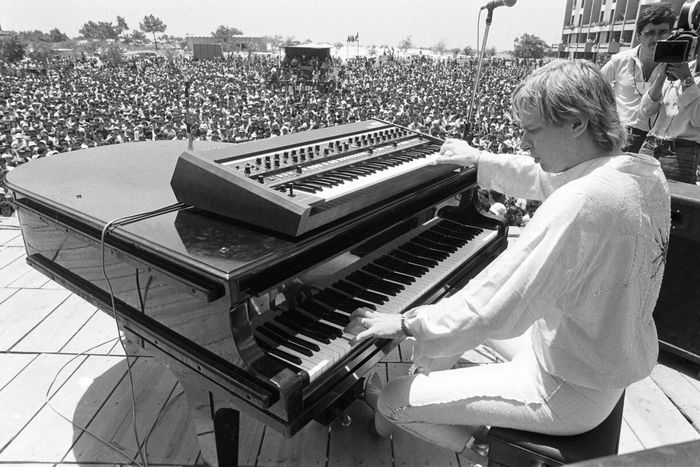

To look upon Wakeman in the 1970s, whether as a member of the group Yes or his keyboard-based solo work, was to witness an alchemist’s blend of fantasy and science fiction. Wearing a flamboyant wizard’s cape and perched behind a bank of cutting-edge synthesizers, Wakeman blasted lore-heavy songs derived on Arthurian legends. After training at the Royal College of Music, he began his career as a session player, mastering any instrument with a keyboard. He once got a desperate call from producer Gus Dudgeon in 1969 when nobody could figure out how to get a mellotron to work for “Space Oddity,” leading to a long association with David Bowie. Indeed, Wakeman later had to make a tough call: join Yes or the Spiders From Mars (he chose the former). At the height of Yes’s popularity, Wakeman left to release three enduring, chart-topping classics: the instrumental The Six Wives of Henry VIII, the Jules Verne–inspired Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and the most British of all concept albums, The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. When he performed that last one, it involved 14 ice-skaters zooming around a stage decorated like a castle.

Wakeman has since been in and out of the official lineup of Yes several times and performed solo piano tours for years. (He makes a return to the United States this October.) While more of a household name in Great Britain, Wakeman’s ethereal-sorcerer persona onstage was matched in his heyday for barroom carousing and insolvency. At the peak of his fame, he often slept in parks thanks to poor fiduciary choices and frequent divorces. He’s sober now and keeps his social-media presence focused mostly on animal rights. When performing a rock show, however, he still straps on a cape. “I love the capes,” he says with a devilish smile. “My father used to say, ‘Be yourself offstage, but be the persona onstage.’”

Best song for newcomers

“Arthur,” from The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. I love melodies, I love pomp, I love huge … bigness. If I could only have written one thing in my life, it probably would be that “Arthur” theme. I wrote most of it in hospital. I was having heart problems and was there for nine weeks. But I had some manuscript paper and pencils and nothing else to do. It was interesting to come home to the piano and hear what I’d actually written.

The BBC has used that theme for most of the elections since 1979, I believe. There was a stretch when they didn’t use it, but there was outcry from the general public, so they had to bring it back. That made me feel quite proud. The only problem was if I was on tour while there was an election on, I found it hard to play that theme — people would say, “Why are you playing the election music?” I’d say, “It’s not election music, it’s King Arthur!”

Favorite Henry VIII wife

Catherine Howard. In Tudor times, they didn’t keep good records. Certainly the death records of Henry’s wives are known — he did chop three of their heads off — but births are muddled. It’s suggested that Catherine may have only been 18 when he killed her. And she was a fun time. I tried to make the piece I wrote about her fun when I recorded it. She must have known what was going to happen, because if you play around while you are Henry’s wife, you know that you’re going to be separated from your body, head-wise.

I also admire Anne Boleyn, because when Henry put her in the tower, she knew she hadn’t done anything wrong. She had tried everything she could to be a good wife to Henry, and it was just the fact that he’d found somebody else. It was a great shame, really, because she was the one wife that really had a lot of dignity.

I enjoy playing all of those pieces still, but my favorite does change from time to time. “Catherine Howard” has a lot of different sections and fun elements to it. “Jane Seymour” is lovely to play, too, because of the church organ.

Yes track he contributed the most to

“Awaken,” because of the massive organ solo in the middle of it. It does last a long time. I know some people, when they are listening to it, they go out and have a meal, then come back and it’s still going.

It was also way ahead of its time. The organ was in a church in Vevey, in Switzerland, and we recorded it down the telephone line, which no one had ever done before. Only the Swiss had high-enough fidelity telephone lines. We simply rented the line from beneath the church nine miles to the studio in Montreux. There was a time delay, but I have a lot of experience with church organs; you learn to not listen to what’s going on and trust yourself time-wise. We recorded the choir part, which I wrote as well, in a similar way. This can be done easily now, but in 1977? Way ahead of its time. The record company should have done more with this in the press.

Yes song he didn’t record but still loves to play

It’s interesting when you are in a band with a history before, during, and after you were there — and a lot of it is successful. I enjoy playing a lot of the material I wasn’t on. “I’ve Seen All Good People” is one I like an awful lot. It’s a clever and fun piece. “Yours Is No Disgrace,” also, and “Starship Trooper” is a great deal of fun. In fact, I play “Starship Trooper” in my own band. I really don’t mind playing the songs I wasn’t on at all.

When I was with ARW — Anderson, Rabin, and Wakeman — it was interesting because Trevor Rabin and I had never been in Yes at the same time together. He did 90125 and Big Generator, and I was on a lot of the other stuff. We came to the conclusion that “you weren’t there for ‘Close to the Edge’ and I wasn’t there for ‘Owner of a Lonely Heart,’ but what would you have done, and what would I have done?” So we played all the parts that were necessary but threw in what we would have thrown in.

Most baffling Yes lyrics

If I’m fair: all of them. All of them have baffling lyrics. But Jon is a wordsmith. He writes things that are meaningful to him and also to other people. I remember asking, when we did “Going for the One,” if it was about aiming for something special in your life, or in the future, and he said, “No, it’s about a horse race.”

I was with him one time and a young American lad came up and said, “I’ve worked out what ‘I’ve Seen All Good People’ is about.” I thought, Right, this’ll be interesting. He said, “It’s all about moving through the different planets and different planes of life,” and he had a whole thing mapped out. Jon says, “Brilliant! Thank you!” and off he went. I asked, “Is that really what it’s all about?” and he said, “No, it’s about a chess game. But if that’s what he thinks it’s about, that’s fantastic.”

Weirdest place he’s been asked for an autograph

Oh, it’s happened in traffic jams, people roll down the windows. I don’t mind it. Another time — without getting into a lot of stories when I was arrested for driving offenses — I ended up in a strange house on the toilet. The lady who owned the house passed a copy of Journey to the Centre of the Earth through the crack in the door, asking me to sign it for her son Jeffrey. Which I did. I met Jeffrey many years later.

The funniest was when somebody asked for an autograph in the middle of a show. This guy was a bit worse for wear, staggering on the stage, “Sign this for me!” So we had a little chat. He had no idea where he was. He was drunk as the Lord. Now, I had my microphone, so I asked, “What do you want me to write?” and my voice echoed through the PA. After the show, I asked the manager if he threw the guy out; he said he was so drunk he just passed out. But before he did, the manager asked the guy if he got his autograph. He said, “Yes, he’s got the loudest voice you’ve EVER HEARD!’”

Album the critics were wrong about

In the early days, critics were terrible to me. They panned No Earthly Collection. Now it’s a bit of a collector’s item, and the press are kind about it. The Six Wives of Henry VIII, because it was an instrumental album, they didn’t get it at all. “Where are the vocals? Where are the songs? What’s this all about?” Well, it’s a keyboard album. “Why?” Because I play the keyboards. “Nobody does keyboard albums.” Well, I’ve just done one! I defended myself quite a lot in the early days. And I was happy to, because I believed in what I did.

Song that made him fall in love with unusual keyboards

I’m very lucky because I came up as synthesizers were being developed. I was the guinea pig for a lot of them. The Minimoog finally gave keyboard players a chance. Beforehand, we were stuck on the side with a Hammond organ or electric piano, and when it came to your solo, everyone had to quiet down. It was awful. But the Moog and Minimoog could cut through concrete. Not only could you be heard, you could be louder than the guitarists. They hated it! It was brilliant! I said to Bob Moog, “You’ve finally put guitarists in your place!”

For “Siberian Khatru,” when there was room for a keyboard solo, I used a harpsichord. Everyone thought I was nuts. I knew a chap from the Royal College of Music, Thomas Goff, who built the most beautiful harpsichords. I called him and asked if I could hire one for a recording, and he asked, “Which classical piece are you doing?” I said, “It’s a progressive-rock album.” He said he’d do it if he could come along. Other engineers from other studios, they all came by and made notes on how to record it. We used harpsichord again on a Yes track called “Madrigal.”

I don’t like to categorize instruments as old or new. They’re all instruments. If you go to an orchestra and see four French horn players, you don’t ask, “Which of you has the oldest French horn?” People ask about my keyboards, what’s old, what’s new. They aren’t a statement of their time; it’s what sounds good now. My big rig has keyboards going back to 1970 right through today. It all works together.

Proudest session recording

One that originally did not have my name on the credits was “Morning Has Broken,” by Cat Stevens, but he’s gone back and put my name on there. Lesser known, however, is the Al Stewart album Orange, specifically the track “The News From Spain.” I love this one. The whole album is a bit overlooked because soon after, Al Stewart went to America and did Year of the Cat, which was huge.

When we recorded “Spain,” it didn’t have an ending. Al just said, “It’s going to be a fade-out,” and told me to do some Rachmaninoff-like things. It just kept going for two or three minutes, which was an exceptionally long time back in the early 1970s. I didn’t know how much of the ending they would keep until I bought the album. I was very proud, especially as a young session player, that they kept what is essentially a piano solo in there. I haven’t seen Al Stewart for years, and I’m going to see him in America this October. I’m very excited.

Most visionary collaborator

David Bowie. I had the pleasure of spending time at his house for Hunky Dory, with this battered old 12-string. He had the Prokofiev knack. You listen to “Romeo and Juliet,” and musically you suddenly are somewhere else. David was the same way. “Life on Mars?” has chord sequences you simply don’t expect them to go where they go. At first, it is standard, the same chords as “My Way,” for example. Then, suddenly, it’s a complete tangent — but it works. I love that. I was quite influenced by it in a lot of the weird stuff I’ve done.

Trickiest part of nailing the mellotron in “Space Oddity”

Keeping the damn thing in tune. That’s the problem with all mellotrons. The more notes you press, the slower the motor got, and then it gets out of tune. No one could make them work, but when I first got ahold of one, I had a way of kind of cheating it. The producer Tony Visconti asked me how I did it, then said, “No, no, don’t tell me, you’ll earn a lot of money from that.” That was, say, 1969, then Gus Dudgeon called me, “Can you get to the studio quickly? David Bowie wants a mellotron with strings, nobody can keep the bloody thing in tune, and Tony says you can.”

We recorded that in about half an hour, then David asked me to do some more piano playing on “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” and “Memory of a Free Festival.” We became good mates and I came back for Hunky Dory. I owe a lot to “Space Oddity.” It’s such a great and clever track. David came from the folk roots. All his songs told stories with melody. We talked about it a lot. When I later moved to Switzerland, he was a neighbor, and we met frequently. I learned more from him about how to work in a studio than anybody. He never treated me as just a session guy. I was part of the project.

Favorite cape

The one that’s missing. I’ve got all the classics except for the one that was made for Journey to the Centre of the Earth concerts at the Festival Hall in 1974. It went missing during my first divorce … I think? I’ve had almost as many divorces as albums.

I’ve got all the others locked away. I don’t bring them out for the one-man shows because they weigh a ton, so you end up doing a backflip. But for the rock shows, I can’t do without them. I don’t feel dressed. It’s like if you are doing Henry V, you don’t wear jeans — you need to put the gear on.

The capes mean a lot to me. And you get a lot of people dressing up at the shows in the audience, which is wonderful. Lots of wizard’s hats; once I saw a family with a dad, mum, and two young children with capes. It was really cool. People sometimes say “prog’s too serious.” No, it’s not! Some of the music is serious, but the way we are is fun. I want people to leave one of my concerts with a smile on their face.