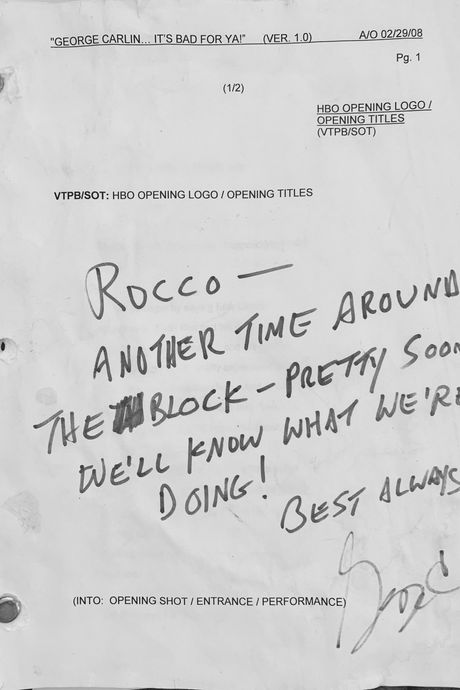

Hidden among all the celebrity interviews featured in Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s new HBO documentary George Carlin’s American Dream (Jerry Seinfeld, Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, etc.), there’s a brief appearance from a lesser-known figure who knew Carlin better than all of them: Rocco Urbisci. As the director behind the camera for Carlin’s final ten HBO specials, beginning with 1986’s Playin’ With Your Head and ending with 2008’s It’s Bad for Ya, Urbisci’s effect on shaping the images fans hold of Carlin in their memories is profound.

Urbisci’s professional relationship with Carlin began in 1980 while working as a writer and booker for The Steve Allen Comedy Hour. A die-hard comedy fan, Urbisci booked comedians he admired, many of whom — like Carlin, Richard Pryor, and Lily Tomlin — he’d later work with on their own shows. Having spent nearly 30 years as Carlin’s friend and collaborator, Urbisci had a front-row seat to arguably the most prophetic stretch of the stand-up’s career. He was behind the camera when Carlin recorded what he personally considered his best special, 1992’s Jammin’ in New York. He anxiously awaited Carlin’s phone call after the September 11 attacks, when Carlin had to change the name of his upcoming 2001 special from I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die to Complaints and Grievances. He was filming Carlin’s final recorded special in 2008, when Carlin was too sick to fly but insisted on performing the show anyway. Since Carlin’s death in 2008, Urbisci has watched the work he filmed take on a second life online, shared endlessly on social media each time a gaping hope in our social fabric is revealed.

Prior to the release of George Carlin’s American Dream, Urbisci shared his thoughts about the new documentary, his personal and professional relationship with Carlin, and how he responds to the people who constantly ask him what Carlin would say if he were alive today.

I wanted to talk to you because I saw you pop up briefly in the new HBO documentary about George Carlin. Have you had the chance to watch it? What did you think?

What I love about what Judd Apatow and Mike Bonafiglio did is that they had Carlin talking about his drug problem, and Kelly Carlin, his daughter, was in the middle of that drug problem, so she talked about his drug problem. But nobody else in the film had to talk about it. That left all the others to talk about his work and his influence. But I knew when I did my interview, I’d have put the odds in Vegas that I’d appear for under three minutes out of the total hour and a half I spoke. But that’s okay! When you’re on with Seinfeld and all those people, you expect that. Plus it’s not about me. I was just fortunate to have a 30-year-plus relationship with my colleague and friend.

How did you and Carlin meet?

I went to The Tonight Show while I was visiting L.A. for a convention, and Carlin was on the show that night. I introduced myself to him, and he asked me what I was there for. I told him, “I wrote a little piece. Could I send it to you?” And he said, “What is it?” I said, “It’s a little film called Captain Catholic.” Then I sang to the tune of the song from Howdy Doody: “It’s Captain Catholic time, it’s Captain Catholic time.” It had two commercials, one for “spray-and-pray holy water” and one for “holy Eucharist cornflakes.” In the middle of it, he stopped me and said, “You know how long I’ve been in this business? I want to stay in this business! I can’t do that. But next time you’re out here in L.A., give me a call.”

That story reminds me a lot of Garry Shandling’s story about meeting Carlin, where he approached him and offered to write him jokes.

Yeah, Garry was a good friend of mine. I did Garry Shandling’s special Alone in Vegas as well. It is ironic that we both pitched jokes to George and he said the same thing to both of us: “Let me know when you come out here.”

Was George generally open to taking young comedy creatives under his wing?

I think he did it without having to do it. If you saw the documentary, you saw what Seinfeld and all the other comics said. Everybody looked up to him. There are two comics that are benchmarks, and we know who they are: Pryor and Carlin.

One of the things I wish the documentary featured more of was insights about who George was as a person offstage. Do you have any anecdotes you can share?

The last show we filmed together was shot in Santa Rosa because George was too sick to fly. I’d always open the shows we filmed with the song “Start Me Up,” by the Rolling Stones. About five minutes to air — none of us knew this was going to be the last show, remember — a producer showed up and said, “George wants to see you.” I said, “This is unusual. Very unusual.” So I went and knocked on his dressing room and said, “What’s up, George?” He goes, “Are you going to play that fucking stupid Rolling Stones song again?” He waited 30 years to bust my balls! I roared. I said, “Yeah, I’m going to turn it up extra loud for you.”

Twenty-two years passed between the first special you filmed for George and your last. How did your working relationship evolve over that time?

In the time George and I worked together, we never had one disagreement. It was all about the work first, not individual preference, which is a fine line to draw. With George, it was always about what’s best for the show. It was about feeding the monster that demands attention. It never got personal. When we said, “This isn’t working,” we didn’t add “for me” at the end of it. We might’ve said, “This isn’t working, and I don’t know why.” But that’s different.

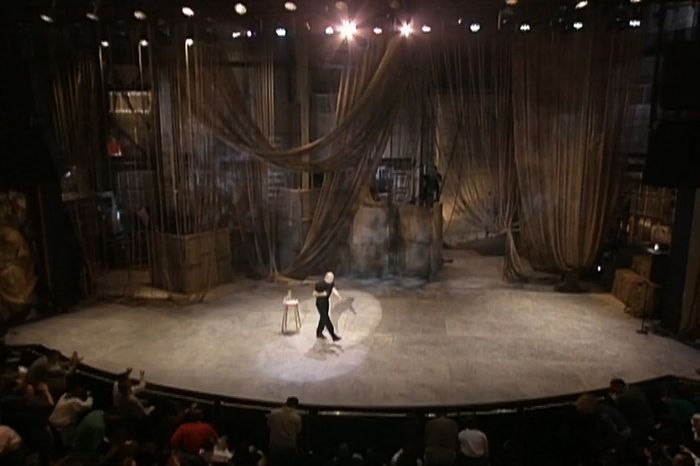

We also both got older and better. The first live show we did from Paramount Theatre in 1992, Jammin’ in New York — which is George’s favorite special, by the way — was the transition George made. People were saying things like, “He’s done,” so it motivated George to unlock the next level of his writing. It was a whole new point of view. It was also the first live HBO stand-up show and my first live stand-up show. They recorded my audio when it started, and they gave it to me, and I sounded so panicked. But then I got calm after a while because it became autopilot, and I went into gear. Every time I worked with him, I got better.

What strategies did you find worked best for capturing George’s work visually?

My peers always want to know how many cameras I used on Carlin — I used five. But the secret was I had two jib cameras in the wings, which would give me different positions, and it made it look like I had more cameras than I had. It was a rock show to me: When the lead singer is doing the lyrics, you stay on the lead singer. When the big moments come, you want to get movement; you want to get the money shot. When I did the first show, I did it on 35-mm. film. There were eight cameras, and I had to cut it all together. But when you’re on live TV, like we were with some of our later specials, you don’t get that option.

The advantage I had is that I knew the act before I did the show. I went to the Comedy & Magic Club and watched the routine. I knew all the subjects that were coming up, so I could make changes on the fly. Plus I didn’t do it alone. I had help from Beth Einhorn and Gene Crowe, my assistant and third directors.

How hands-on was George with the visuals?

The only time he ever came to me and our production designer, Bruce Ryan, and asked for a set was the second to last show we did with him at the Beacon Theatre. It was a graveyard set. I thought it was a strange request. But he wasn’t well at the time. It makes me wonder.

Carlin has so many enduring bits. As someone who saw his mind work, what do you think it was about his comedy that made him so prophetic?

He told the truth. There was no sugarcoating on it: This is how it is, folks. Garbage in, garbage out. I get asked all the time: “What do you think George would say if he was around today?” Go watch his specials — he said it 30 years ago! You want the guy to walk out at 98 years old and do jokes? Get serious! It’s totally fucking selfish. I want him around, too. But I don’t want him to have to be a comedian anymore. I just like having him around. We were comrades in arms.

When you watch comedy today, do you think there are comedians carrying forward the torch George lit?

I’m not going to single out anybody, but I think there are some. But here’s the disadvantage they have when it comes to being revolutionary: We’ve been so inundated with shit. What is new to us now? Do we have a climate problem? We had it before too! We had a crime problem back then — we still have a crime problem! So if you’re a comedian, what are you going to talk about that we don’t already know? You want to talk about transgender people? Okay, but it better be smart and brilliant because that’s not new, either. There’s so much information we’re bombarded with every day. Just go watch George on YouTube.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.