Rosalind Fox Solomon has almost never worked on assignment. When she first started taking photographs with an idea of making art, no one would have expected her to turn that into a career; she was heading into her 40s with two children, a woman learning to communicate as she hadn’t been able to before. She started out shooting close to her home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even after she started gaining recognition and traveling farther afield, she didn’t exactly have a long-term plan: She would, she says, just decide to go somewhere — occasionally because of a disruptive event, like an earthquake or a flood, but usually just because, hiring a guide and a translator if she needed one. In India, Guatemala, Brazil, or Missouri, she’d move around and look at people, engaging them but not saying much, and come back with pictures. That’s it.

Did she think about what collectors or publishers or editors might want, the way so many photographers do? “First of all, I’ve never been commercially viable,” Fox Solomon says now. “I never thought about that. Really, I just worked. Piled up my prints, year after year.”

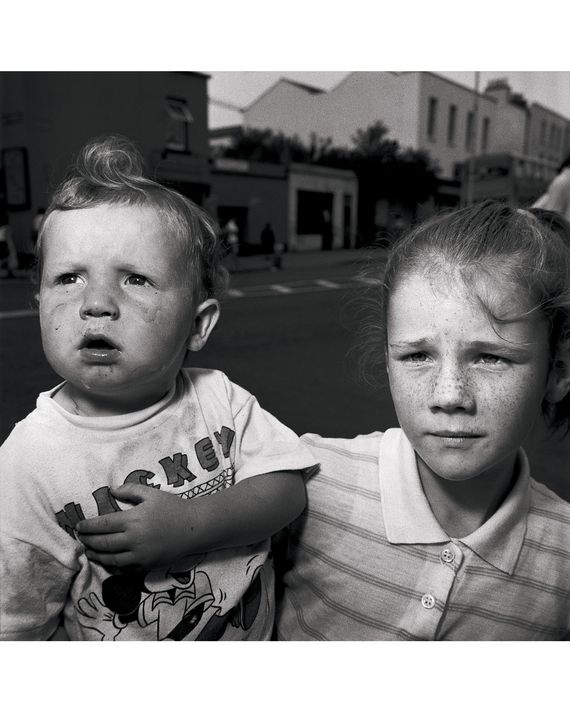

We’re speaking in Washington Square on a perfect October day, a few blocks from the building where Fox Solomon has lived since 1984, when she was 54 years old and recently divorced. She’s 91 now and hasn’t stopped working, spending the majority of her time these days collecting and editing her older work for publication. Recently, MACK published The Forgotten, her new selection of 40 years’ worth of portraits; today, a solo show opens at Foley Gallery, incorporating many of the same pictures. Fox Solomon is not a mission-statement kind of artist — “I don’t have a relationship to some of the issues I’m pointing to in The Forgotten,” she tells me as we start paging through the book — but a mission of sorts seems to unspool anyway. Fox Solomon made these photographs almost everywhere on the globe where people have been trodden down during her lifetime, sometimes by natural forces, but particularly by imperial America.

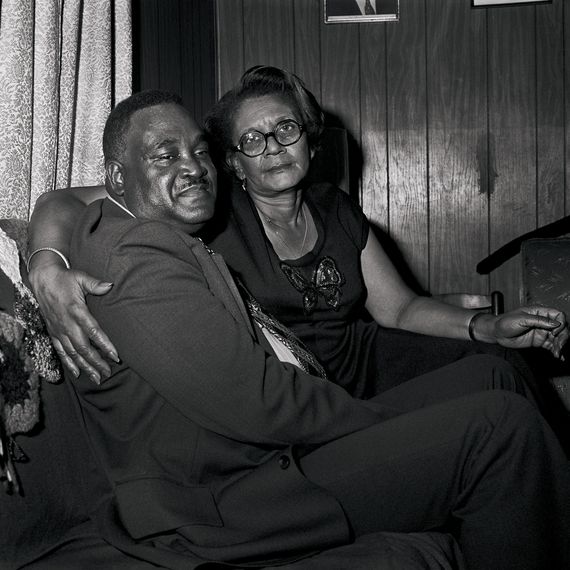

Black-and-white portraits from all those places — and Havana, rural Peru, Phnom Penh, and many others — fill the book. (As do some from Washington Square, including one view of people on a bench identical to the one we’re sitting on.) Of a photo made in Istanbul, Fox Solomon says: “This is a wedding on a boat on the Bosphorus. I was astounded. This is a belly dancer. And he’s pushing money onto her face.” In Guatemala in 1992, two people lie in a roadside ditch as their child watches over them. “Was someone hit by a car?” I ask. “No,” she replies. “They were drunk. Oh, what a mess. And the child would have to sit there until they slept it off because they weren’t near home.” A Black couple in Chattanooga, the woman showing a playful sly smile: “She was a janitor in the city hall. She knew everything about all the politicians.”

It’s difficult to slot Fox Solomon’s work into a photographic niche. Her social conscience isn’t usually front and center the way it is in, say, Gordon Parks’s epic photographs of the segregated South, where an actual neon sign tells you what’s horribly wrong. The more obvious and perhaps glib comparison is to Diane Arbus, and there are a few similarities: the centered faces, the two-and-a-quarter-inch-square film format. But Arbus’s images are renowned for their relentlessness; Fox Solomon’s are more generous, even when she’s shooting questionable people and places. They’re about who the subjects think they are as much as who we see them as. The psychological layering is conflicted and oblique. “The depth is in the pictures, not what I say about them,” Fox Solomon says. “They represent many strands of emotion and connect to realities — sociological, historic, and political — and I’m interested in the inner as well as the outer.”

To hear her tell it, the camera was the tool with which she also discovered herself, and it happened a little bit by accident. Rosalind Fox grew up in a nice suburb of Chicago; her father had done well in the wholesale-tobacco-and-candy business, and her extremely dependent mother hoped for her daughter to become, as Rosalind says now, “a lovely woman.” Her sister, in conversation with another family member, explained the situation later on: “Rosalind was not like us. She was completely different, and we never understood her.” It was a well-off home with a full-time live-in maid but (going by the bits of biography in a previous book, Got to Go) not a happy one: Her father was unfaithful, her mother once tried to kill herself.

After college, she says, “I wasn’t that confident, and I was … kinda lost. I was lost.” She got a couple of jobs and traveled with the Experiment in International Living, the summer-abroad organizers. At 23, she married a well-off, politically connected Southerner who eventually became a real-estate developer, Joel “Jay” Solomon, and moved to Chattanooga. It was 1953. “He was a good man,” she says, but “I wanted to keep working, because I liked working. And my husband said, ‘No wife of mine is ever going to work.’ I’m not kidding you.” They had two children, and Fox Solomon eventually occupied herself the way Chattanooga housewives with a social conscience did, volunteering with liberal causes — the League of Women Voters, civil-rights groups — in between giving dinners for her husband’s dull business associates. “So I was doing something that I wanted to do, but I was also living an upper-middle-class life, you know?” She took guitar lessons to try to shake off the ennui, and rode horseback every week.

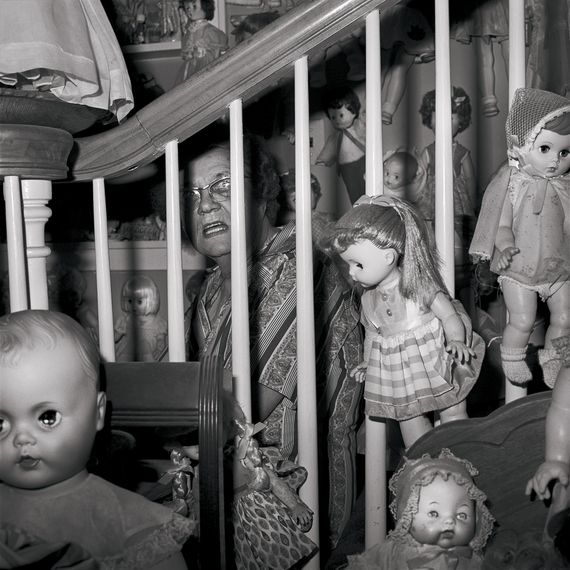

In 1968, something snapped in her. After the King and Kennedy assassinations, she gave up her activist work, depressed. She’d been working as an equal-opportunity recruiter for a group called the Agency for International Development but chucked the gig when she realized that a lot of the jobs she was filling were in Vietnam, effectively propping up the war. “I turned inward,” she says. She also started taking pictures, first with a camera she bought for a cultural-exchange trip to Japan. Groping to express herself and unable to speak Japanese, she discovered that she could convey through the camera some of what she was finding it difficult to say: “It allowed me to put in the forefront parts of myself that I had not yet realized — that had not yet been in my consciousness.” In the early ’70s, she started going to an Alabama flea market to make still lifes of broken dolls, an artistic breakthrough of sorts. Gradually she migrated from the dolls to portraits of the sellers and their customers. In an attempt to fit in when she visited, she tied on a frilly poke bonnet. (“Obviously they knew I wasn’t a farmer,” she says now.)

Although Fox Solomon wasn’t aware of it, she was discovering this medium precisely as it was coming into its own. Photographers had been regarded as artists before, of course — Stieglitz and Steichen, Margaret Bourke-White, Lisette Model and her contemporaries — and MoMA had started a photography department a generation earlier in 1940. But the form was still slightly deprecated by much of the art Establishment, who thought of photographers as technicians more than conveyors of thought and depth. There were few collectors of photographic prints and only a couple of serious dealers, and you could buy extraordinary work for pennies. Arbus’s sensational, troubling pictures — and her rising public image after her 1971 suicide — were among the forces beginning to break down that wall. Fox Solomon says she knew of only two photographers by name when she started making pictures: Diane Arbus and Ansel Adams.

In those years, she would accompany her husband when he came to New York on business, and while she was here she would get her work printed by Modernage, one of the city’s big processing labs. In the early ’70s, she met a woman at the lab’s Christmas party who eventually led her to Model, the great mid-century photographer who had taught Arbus some two decades earlier and who was famous for her incisive portraits of ordinary people in ordinary settings in France and New York. Model told her to “bring everything you’ve ever done.” Fox Solomon showed up with suitcases full of prints, and the older photographer “looked at my things for six hours. At midnight, we were both exhausted, and she said, ‘Yes, I will take you on.’”

She had lessons with Model a few times a year on those trips to New York. (Her children were teenagers by this time.) The work was demanding, and not just because Model was a drill sergeant. There were basic classes in lighting and a field trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they were “looking not only at the nice objects but also things like the fire extinguishers or an outlet for heat or something — noticing everything.” Model ordered Fox Solomon around as she worked: Do it from below. Do it from the side. You can’t just stand in the same position — get lower. “The thing I really didn’t like about the lessons, I later learned was really good: She would always talk about herself for a half an hour before she would look at anything of mine,” says Fox Solomon. “What was happening with her work and who she liked and who she didn’t, the photographers who were famous that she thought were shit. And I was going crazy, you know, because I wanted her to look at my things — but in the end, I learned a lot.”

At first, Fox Solomon shot 35-millimeter film, but soon she shifted to two-and-a-quarter-inch black and white, the square format that frames a face so well. Sometimes she made good pictures within the world she’d come to know: In one, a blond Tennessee senator, Democrat Jim Sasser, is shown hugging his two kids while his wife’s arm sticks into the frame, cupping one child’s head from above; the family was clearly going for playful Kennedyesque roughhousing, but the scene is tense and anything but casual, particularly under the hard light of Fox Solomon’s strobe.

Another time, she photographed Jimmy Carter in Plains, Georgia, before he was president. “My son kept telling me, ‘Mother, you should be photographing Jimmy Carter.’ I was photographing broken-up dolls, and I didn’t want to stop — I thought that was very important, what I was doing.” But she was persuaded to turn up one day when Carter was dredging a pond, and made some amazing pictures of the born-again president, standing in the water in his denim shirt. One of them is on the jacket of Kai Bird’s new Carter biography. (Fox Solomon’s husband would later work for the president, as head of the General Services Administration.) Another of her books, Liberty Theater, gets into the racial dynamics of the Deep South in the 1970s. The pictures suggest that Fox Solomon had immersed herself in the Black culture of the South, because her subjects don’t seem highly guarded, but she is matter-of-fact about her limits: “I don’t know how much I did it. I mean, my friends in Chattanooga were activists and liberals, and when I think about what we really did or didn’t do, it makes me feel very guilty. Your associations are not as broad as they should be. Because I still lived there, you know?”

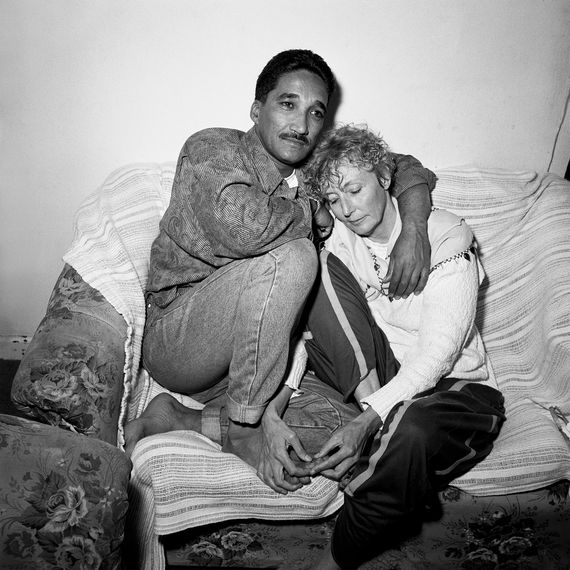

She began to show her work, first in a group exhibition in Chattanooga. A series she did in Israel, titled “Roses and Radishes,” traveled to several American synagogues in 1974. (Today she calls the pictures “tourist memories,” and and hints that they’re somewhat naïve compared to her more recent work photographing Palestinians.) By 1980, she had a show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; in 1986, she had a solo exhibition at MoMA. On a few occasions, she ended up training her lens on powerful people again, often on very short notice: in Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama (“That was weird: I was wearing work boots and a kurta and pants, and he said to me, ‘You look like a Russian!’”), and in New Delhi, Indira Gandhi (“She came out, and she sat on a chair, and she didn’t say a word”). In most of her photographs, however — especially the work she made after she ended her marriage and moved to New York — she’s looking into the faces of people who are living somewhere near the edge of the abyss. Arguably her most celebrated body of work is from New York in the late 1980s: pictures of people with AIDS, most of them young, most of them men, often with the lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma visible on their skin. (They were shown at the Grey Art Gallery, right by where we’re sitting in the park; at the time, the New York Times claimed she was sensationalizing her subjects, a criticism that today seems thin.)

“I’m always thinking, Who is this person? What does this person think about and feel?” she says. She attributes her ability to filter into these situations to her look: her photographer’s vest, her chunky glasses and basic loose clothes, and (today) her white hair. “I don’t intimidate people — I just look like a kooky old lady,” she says. I offer, tentatively, that she might somehow convey that she’s something of an outsider herself, and she seems to agree. “They just didn’t get me,” she says of her family. “I was very serious as a child, and I felt very rejected. And I feel that some of my going into unknown environments — meeting people wherever they were, even on the road, and being accepted — partly came from that sense of wanting to be accepted. Which is crazy.” Well, the book is called The Forgotten, so … “Yeah. You know, I’ve never said it, but I’ve thought about that. How I would go to a country as a stranger, and I would at least briefly feel that I belonged in one group or another.”

Although Fox Solomon has been shooting less lately, she does still get out there. When MoMA asked her to work on a new series from scratch in 2019, she says, “I didn’t tell them I hadn’t had a camera in my hand for several years” and jumped in, taking one of her very rare commissions. (One of the portraits she made at the museum, of a worker who’s been painting gallery walls and poses with his roller and tray, appears in the new book.) She’s planning to create a new body of work for her next book, about whose subject she is discreet. Walking back from the park, we talk about the exercise classes she’s been doing. She does a little time on a stationary bike, stretches, some other low-impact stuff. She’s particularly into the Alexander Technique, a set of posture modifications that are said to affect not only the body but the mind. “If you’re like this” — she looks at the sidewalk in the middle distance — “you don’t feel as good. And then you lift your head like this” — she raises her chin and stands taller — “you feel better. You do.” Her pace quickens as she heads for home.