Dawoud Bey’s work is both a documentation and an excavation. The photographer is preoccupied with history and its effects on our contemporary experience, chronicling the America that resides largely in the shadows and bringing it closer to the center. Often depicting Black subjects, Bey understands that the collective aches we feel today are the remnants of yesterday’s agony, attesting to poet Audre Lorde’s verse: “And there are no new pains.”

On April 17, Bey’s retrospective exhibition “An American Project” opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art, with photographs made over the nearly five decades of the native New Yorker’s career. In Bey’s 35-mm camera images, his Polaroid portraits, and his large-format landscapes, we feel both the passion and contempt that he holds for his complicated country: In a street corner filled with rubbish, Bey sees the poetics of home. In a boy at a bus stop, he sees a Rembrandt painting. Where one sees an ocean, he sees the people who drowned in route to freedom. His visual poetics show the America we want to forget.

“It’s a very odd moment because the retrospective kind of pulls you back into a conversation that you’ve already resolved,” says Bey, speaking from his home in Chicago on a recent Saturday morning. In addition to the Whitney show, he has a new monograph coming out with MACK Books, Street Portraits, as well as some work in the New Museum’s current exhibition, “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America.” Meanwhile, he’s preoccupied with his newest conceptual landscape project, which involves making photographs at the sites of four former plantations in southern Louisiana, along the west bank of the Mississippi River. (No matter where his work pulls him, he always follows the water. Proving that water is a body too.)

It’s been nearly 50 years since Bey started making work. But he remembers the street corners, the names, and the way his heart was beating when he encountered every subject. He welcomed the chance to discuss six photographs that represent pivotal evolutions in his career — with every image elaborating on the concepts preceding, a navigation through the power imbalances between subject and shooter. —Sasha Bonét

A Man in a Bowler Hat, Harlem, NY, c. 1976

I would say that everything that I know about making photographs comes from this photograph. When I saw this man, on Sunday morning on 132nd Street near Adam Clayton Powell, he was standing with a group of maybe three other older men having a conversation. I spotted him and knew that I wanted to make a photograph of him because of the way he was dressed. He was a clear visualization to me of Harlem’s past in the contemporary moment. He could have been standing there in 1920 or 1930 or 1940.

I only wanted to photograph him, not the group, and I didn’t quite know how to do that yet. I had no formal training up to this point and had largely self-educated myself by spending time in different galleries and museums, looking at the work of James Van Der Zee and Roy DeCarava and Irving Penn. When I got up to them, I couldn’t figure it out, so I said good morning and kept walking. I got to the end of the block. I was having this intense conversation with myself; I suddenly realized that this outing was going to be a little more complicated than I thought. The social dynamics involved with photography are about momentarily inserting yourself into the lives of the individuals in order to make the photograph you want to make. I realized in that moment that if I couldn’t figure this out, I wasn’t going to be able to do and be this thing that I imagined myself being because it was clearly going to continue to come up.

So I turned around and started walking back. I just fixed my gaze on him and I said, “Hi. How are you? I really love the way you look. Do you mind if I make a picture of you?” Which is to say: Do you mind if I affirm your presence? It’s the first time that I saw in my work the thing that I was hoping to see.

A Young Man at the Bus Stop, Syracuse, NY, 1985

This was made during the first time I was invited to do an artist’s residency. The idea that someone would give me a stipend and an apartment — and every day for 30 days all I had to do was get up and work from sunup to sundown — it was an extraordinary gift. I wanted to focus on the African American community within the landscape of the city.

I have a long love affair with light and the evocative quality that light imparts on the landscape and on the subject. I was looking at the lines on his warm-up suit and the coherence of the spatial geometry and the narrative of space and place. Look how he styles that Kangol in his own particular way. It’s a very conscious set of choices that he’s made in his self-presentation. At this point, I would basically do anything. I had developed a confidence to insert myself into a wide range of social situations and I was just standing there, waiting. I spent a lot of time on both sides of the street at that corner, measuring the light at different times of the day.

This man just ignored me, but he knew I was there. He was the lone figure in the triangle amongst the light and dark and shadows.

A Girl with School Medals, Brooklyn, NY, 1988

This girl had pinned on all her school medals. One of them was track, one of them was dance. She was really active in school. This is probably the end of the school year. She got her medals, she pinned them on, and she was walking around the neighborhood — she was passing by on the block I lived on in Brooklyn. I wanted to affirm that: Oh, I love those medals! I’m so proud of you. We’re all proud. The whole community is proud of you. She did good, so let me immortalize her in a photograph.

I had started making black-and-white Polaroids on Cambridge Place between Fulton and Gates in Clinton Hill. I used to see Biggie (Notorious B.I.G.) because we worked on the same corner every day. He had a hard-core persona, so I never approached him to photograph him. But I knew him and he knew me. These became the Brooklyn street portraits, and I had an exhibition of the photographs in Brooklyn, which is another piece of the process: I wanted the people in the photos and people in the community to have access to the photographs that I made. I made them in Brooklyn so I wanted folks in Brooklyn to see themselves. And that continued in my work.

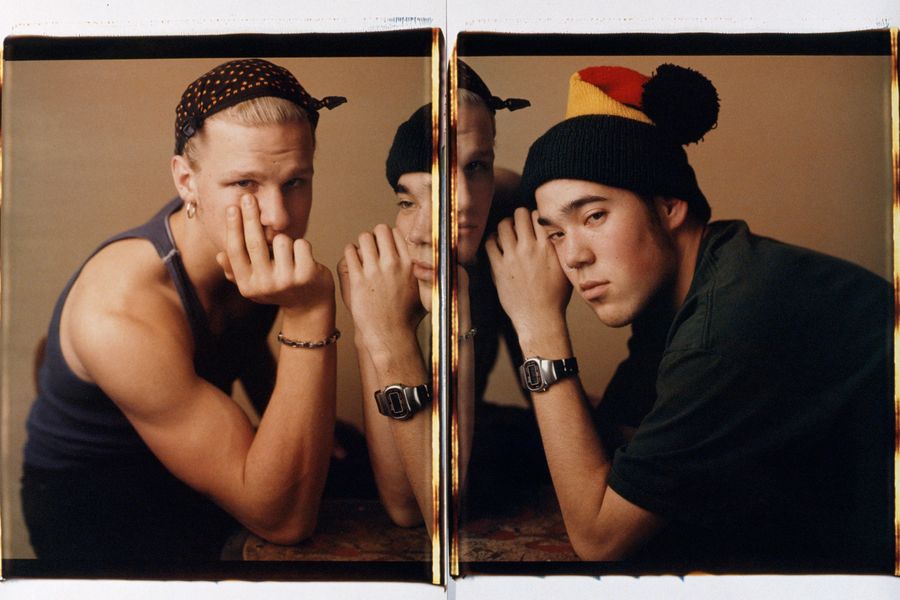

Hilary and Taro, Boston, MA, 1992

This work moves toward a more deliberate kind of process that also takes into consideration, conceptually and materially, the idea of reciprocation. None of those people in my Syracuse photographs ever saw their photos. I started to become uncomfortable with that. Even when I was photographing in Harlem in the ’70s, I would make eight-by-ten prints and carry them around in my camera bag so that if I saw the person again, I would give them a print. Polaroid had an Artist Support Program, where they would grant artists time in the 20-by-24 studio in SoHo and provide the film. I started working with the Polaroid positive-negative film because I could make an instant print that I could give to the person in addition to the negative from which I was able to make exhibition prints later. This was a much more deliberate, slower way of working that demands an even greater degree of consent and reciprocity.

This photograph was initially inspired by my encounter with Rembrandt paintings. Even the warm-brown backdrop that I’ve set up and the single light source were entirely related to what I found interesting about Rembrandt’s work. Hilary and Taro were high-school students in Andover, Massachusetts, who had agreed to sit for me at my residency at the Addison Gallery of Art. It’s one of the first successful diptych realizations of a more complex way of thinking about the multiple images in relation to time and a shifting psychology. It was the beginning of a new way of making and thinking about my work.

There are fundamental problematics in the imbalance in the relationship between subjects and photographers. But this way, they’re able to both confirm and affirm the way that I was seeing them. I’m not passing judgment, just allowing them an arena to describe themselves to me and by extension to the viewer. With these two, I like their own individual sense of style and how they are performing coolness for the camera. The demeanor of the subject in the portrait is always somewhere between natural and staged, since it’s an unnatural situation. I wanted to eliminate the narrative of place. And to focus more resolutely on the subject.

Mary Parker and Caela Cowan, Birmingham, AL, 2012

In 1964, when I was 11 years old, my mother and father went to hear James Baldwin lecture at the church I grew up in. They brought home a book called The Movement. There was a photograph of Sarah Jean Collins lying in the hospital bed with her eyes covered in gauze bandages from the dynamiting of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed her sister, Addie Mae Collins, along with three other girls on September 15, 1963. I’m not sure that I intuited that I was the same age as she was, but that photograph was seared into my psyche. Then, in the middle of the night in 2005, that picture came rushing back with such a force that it made me bolt upright in bed. That’s when I decided to go to Birmingham.

My series “The Birmingham Project” was a real conceptual shift in my work. This is the first of what turned into a research-based project. The four girls had a kind of mystic and abstract presence. I knew that I wanted to make work that gave them a more tangible, palpable presence. What does an 11-year-old girl look like? Not four little girls as a group. I decided that I would make portraits of young people in Birmingham who were the exact same ages as the children killed in the bombing and of people who were the age that the girls would be were they alive today.

One woman subject said, “You know, you’re making me remember things.” They were all haunted by the memory of that moment. Some of the sitters knew some of the girls. Some of them remembered feeling the blast. Birmingham was once called Bombingham for all the bombs that would detonate. When Caela walked in, she was so small, and my heart just caught. And then, when she got in front of the camera, her whole disposition changed. And she was fully present. That intensity of focus and engagement.

This was the moment in this project when I stopped working and I went home to regroup. You realize why people didn’t want to talk about this moment: It’s not something that you want to remember, but we have to.

Untitled #25 (Lake Erie and Sky), 2017

This was the final destination in America of the underground railroad. It’s 50 miles across Lake Erie to get to Ontario, to get to freedom. Many of the locations of the route are unknown. For my series “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” I wanted to imagine the Black subject without placing them in front of the camera — but rather by placing the viewer in their path. The darkness of these locations made me think of Roy DeCarava, and then Langston Hughes’s poem came to mind, “Dream Variations,” where he writes: “Night coming tenderly / Black like me.”

This was the last photograph that I took for this series. When I was setting up the camera that day in Cleveland, I felt this absolutely palpable presence of hundreds of people standing around watching me work. That’s when I said, This ain’t a place of the imagination, you are standing at a site because their presence was there. It was almost like I could look up and see them. Those that crossed here. This was also the largest photograph that I made, because I wanted the viewer to feel the place, to embody the physicality of the landscape on this scale. Black people had to go in and out of the water in order to wash away their scent if the dogs were tracking them. And the water is also how Black people were brought to this country. Water is an important part of the Black experience, and it holds memory, even when we don’t.

*An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the Hilary and Taro image was made in Chicago. It was in fact made in Boston.