Before the wedding of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer in July 1981, the club kid and singer Boy George went to Stephen Jones to see about a hat to wear to a party planned for the big day. “Of course, he didn’t have any money, so we did an exchange,” Jones recalled recently. “He worked for me for two weeks, sewing, and I made him a hat.” That’s how it was in the Britain of the late 1970s and ’80s, a period of high unemployment and pessimism that helped to ferment punk and the New Romantics. The Blitz club was opened two years earlier by the musicians Steve Strange and Rusty Egan, whose door policy — only “the weird and wonderful”— ensured outrageous dress, indeed a kind of deeply English imagination. Jones himself was barely out of college when he began making hats.

“It was really for friends,” Jones said. “No knowledge is much better than a little knowledge.” For Boy George in the summer of 1981, he designed a white-plumed helmet inspired by the warrior queen Boudica. “And these were all people,” he added, “before they became famous.” He smiled, an eyebrow going up. “Right place, right time.”

That expression could well describe the milliner’s career, pieces from which are on display in Paris in “Stephen Jones: Chapeaux d’Artiste” at the Palais Galliera until March 16, 2025. The so-called Blitz Kids brought him to the attention of the renowned buyer Rhoda Ribner of Bloomingdale’s. Jones didn’t even have an invoice book when Ribner turned up at his London studio, but he knew about Bloomingdale’s. “It was absolutely the place worldwide,” he said. At the time, he didn’t have any retail accounts, but thanks to a British Vogue editor named Anna Harvey who was helping Princess Diana with her clothes, he soon had a very important client.

“I was making hats for Steve Strange on one side and for the Princess of Wales on the other,” Jones recalled. “We had the wife of the governor of the Bank of England, but we had one fabulous lady of the night who bought the most expensive hats — and paid cash. And she looked great.” By 1984, Jones’s inventive hats had captured the attention of Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler, and the milliner’s dream — any milliner’s — of working with the best of the best in Paris had become reality. Right place, right time.

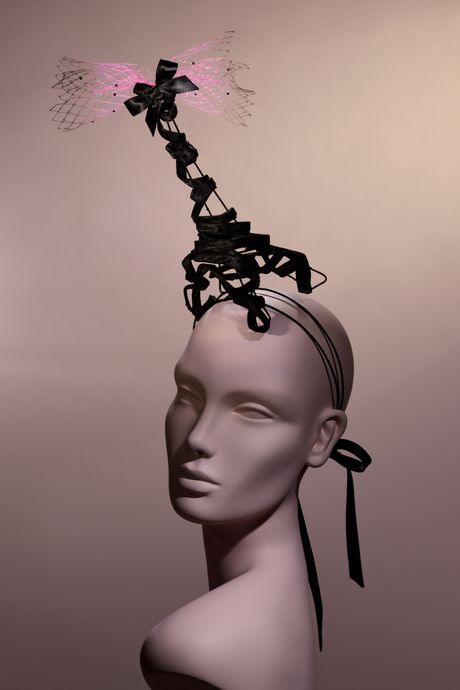

The Galliera exhibit focuses on Jones’s relationship with Paris, both in terms of inspiration and collaboration. Although he has worked with designers and private clients across much of the world, notably Marc Jacobs and Thom Browne (as well as the late L’Wren Scott) in New York, only the gear he made for them in Paris is on display, such as the high-domed, gently dented hats the models wore in Jacobs’s 2012 Louis Vuitton show as they stepped off a steam train. The list of houses Jones has worked with is long and varied and includes Alaïa, Schiaparelli, Claude Montana (both his own brand and Lanvin), Comme des Garçons, John Galliano, Givenchy, and Dior. He has worked with Dior continuously since Galliano enlisted him in the late ’90s, and technically, it’s the only French house that still has a millinery atelier. In the past, of course, most couture houses employed hatmakers.

In many ways, Jones is a bridge with history. He’s not the sole surviving link to this particular form of self-expression — there are other great contemporary milliners with a sense of history and wit, notably the Irish-born Philip Treacy in London. But he’s certainly a key link. One reason the exhibit is so engaging (aside from the built-in charm of hats) is that it combines Jones’s personal story with examples of historical millinery from the museum’s collection of 4,000 pieces. There’s original headgear from Christian Dior, Cristóbal Balenciaga, and Elsa Schiaparelli, among others. There’s a capacious 19th-century bonnet alongside one Jones created, and a knitted cap from the French Revolution displayed in its crêpe-thin box and proving, again, that nothing is new.

Designers of all stripes get ideas from the past, but it was curious to me to see which objects and images mattered to Jones. Some were obviously personal, such as a pair of his father’s rugby caps from Liverpool, where the Jones family lived for several generations, operated a hauling business (first horse-drawn, later engine driven), and Stephen grew up with two older sisters. “He was a star rugby player,” Jones said of his father. “If war hadn’t come, he would have probably played for England.”

Also on display is a hat Jones created years ago from family photos, including a snapshot of his grandfather’s Cadillac. “He imported cars from America — that was his passion,” Jones said. And Liverpool was a gateway to the world.

Several other hats stand out. One, called Charles James, is from 2017 and designed for Jones’s own label. Made of padded channels of gray satin and shaped rather like an oversize jockey cap, it recalls James’s famous 1937 jacket based on an eiderdown quilt, a design that has inspired everyone from Rick Owens to Lee McQueen to, most recently, Pieter Mulier of Alaïa. For Jones, the eccentric (for its time) jacket was one of the things that first drew him to fashion. He saw it in an exhibition in 1975.

Another hat that inspires a mixture of wonder and tenderness features stained pages of Robert Burns’s poetry wired together in a kind of small cyclone. Jones made it for the late model Stella Tennant to wear at Ascot. She wanted a hat, he said, that reminded her of “walking on the moors.”

There are about 400 works in the exhibition, including more than 170 hats. Curators have re-created Jones’s studio, his profession’s tools, and a video showing him making hats from scratch. The exhibit is worth seeing if you’re in Paris, perhaps especially in light of the pressures on the craft tradition, and on creativity.

During my visit to the museum with Jones, I asked if finding supplies and trained workers is difficult, and he replied, “Oh, how long have you got?”

“I suppose it’s hard in the clothing business, too,” I said.

“Yes, but hats, times ten,” he added. “Everybody loves to say they’re a milliner but actually often don’t know how to do the level that I need.” He pointed out that millinery supplies have always come from around the world — felt from Germany and Portugal, for example, and straw from China and Ecuador. But in many places, such as China, where straw for hats was produced by people at home, those workers can now earn more money in factories producing phones and other new consumer products.

“That sort of handwork” — that is, for straw — “is not the way the world is moving, but I really need it,” said Jones. And that sense of time and change is worth keeping in mind as you look at this purely delightful and imaginative fashion.