Maybe it’s just me, but it feels like 2020 could have gone better? Something about it just felt … off. Yet somehow the theater managed to be excellent, even as the world slid away. With only two and a half months for its in-person season, and then an odd, taffy-time period that could laughingly be called “the rest of the year,” theater artists nonetheless made so many gorgeous objects that my year-end “top ten” was as hard to assemble as ever.

Some of the shows I loved most were comebacks — Haruna Lee’s Suicide Forest had another run with Ma-Yi, for instance, but I had it on my top ten for 2019, so I won’t repeat myself. Others haven’t opened yet, technically, so I’ll zip my lip about The Siblings Play and Six. Nor am I listing the many wonderful audio-only projects, despite their evident theatricality; I was swept away by Gelsey Bell’s CAIRNS, Jillian Walker’s Songs of Speculation, and the Public Theater’s podcast of Richard II. My trophy for fastest and wisest New York acclimation to digital streaming goes to the Irish Rep (sláinte!); the award for best entertainment-to-benefit-ratio goes to the 24-hour Ars Nova Marathon; and a Zoom applause emoji goes to the exquisitely performed reading of Eisa Davis’s Bulrusher, in which Kara Young continued her unstoppable march towards stardom. And finally, a laurel must also go to every artist who chose not to make something this year. We honor all that silence and study.

10. Fly Away

Ducking under the wire of this year came this wordless, in-person puppet show, mounted in a pop-up theater built into the corner of the Petzel Gallery. Fly Away was the performance component of Derek Fordjour’s gallery show Self Must Die, a meditation on Black death otherwise consisting of massive paintings and sculptural groups arranged like shrines. Twice a day, a cohort of white puppeteers (directed by co-creator Nick Lehane) operated a wooden bunraku puppet — mahogany limbs bright in jockey silks — as the three-foot-tall figure danced through a history of Black showmanship in America. The puppet leapt for a ball like Magic Johnson; he crouched low over an invisible horse; he strutted in a drumline. Eventually the puppet rebelled, trying to escape his operators, clawing at their hands, pulling his limbs out of their grasp. It was a testament to the exquisitely produced show that I kept thinking he could make it without them — a miracle seemed so close at hand.

9. Circle Jerk

Patrick Foley and Michael Breslin’s megahype online comedy, which converted a stage play into a fusion of Instagram content and live-shot The Honeymooners episode, included one million jokes about dramaturgy, a tart analysis of online activism, and a couple of big axe-blows at gay white supremacy. Somehow, they made the thing in quarantine conditions: Borrowing camera techniques from live sitcoms and the sweaty vibe of theatrical production, Circle Jerk actually belonged in the virtual realm — no longer a film or an adaptation, but rather some digital country’s first native. All farces do not serve all people, and the team’s rat-a-tat dialogue worked best for those who shared a given set of references. But even in moments you felt lost, there was a dazzle, the firework glitter of satirists working in a frenzy. And in that light, you saw a new form being born.

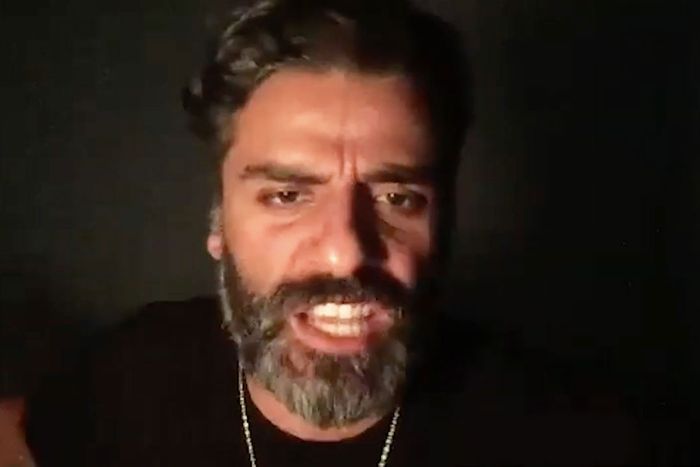

8. The Oedipus Project

Back in May, Theater of War Productions’ broadcast of Sophocles’s drama was the first reading-via-Zoom performance that truly reached through the screen. Even months later, its memory still triggers aftershocks. Much of that power came from the astonishing cast: Oscar Isaac as the blinkered, then blinded king; Frankie Faison as the shepherd letting the truth leak slowly out of him; Jeffrey Wright as Tiresias, full of knowing scorn. Other Theater of War Productions readings have been strong, but Oedipus proved the gold standard. In May, Bryan Doerries used the ancient play to focus us on questions of plague, but the production refuses to be forgotten — it twists in memory, shaping itself to each wave of tragedy. Back in the spring, it was a story about rotten leadership and public health. But you can still hear Oedipus’s anguished weeping as you turn your mind to other errors, other faults that can be admitted but not undone.

7. A Soldier’s Play

This January, the Broadway revival of Charles Fuller’s 1981 Pulitzer Prize winner did only a quiet business. (Perhaps, 40 years on, it felt a bit too Law and Order: WWII Army Base Edition to make the formalists and trend-chasers swoon.) But the play, based roughly on Melville’s Billy Budd, is built with exacting care. While Fuller’s plot chugs along as a whodunnit, the playwright plants the real clues, all of which point to the double consciousness that can poison a Black mind from the inside out: The closer Fuller brings us to finding the story’s villain, the closer we come to undoing our understanding of villainy at all. Only a great actor can tackle that part, and in Kenny Leon’s production, the titanic David Alan Grier played the troubled Sergeant Waters. It was the performance of a lifetime — outsized and yet microscopically observed, frightening and pitiable, monstrous and human. It was the sergeant’s play.

6. Mud/Drowning

The long-lived experimental company Mabou Mines presented two short María Irene Fornés plays, both directed with force and brio by JoAnne Akalaitis. In Drowning, superstar composer Philip Glass headed back downtown to create a new “pocket opera” out of Fornés’s sour little morsel; in her pencil-sketch plot, a grotesque walrus-man falls unrequitedly in love and suffers. The story made a stunning match for Glass’s sawing melodies, which manage to drive the creature’s despair deep first into your nerves, then your bones. Glass also provided incidental music for Mud, one of the much-missed playwright’s masterpieces, in which a woman tries to escape her narrow life but only finds violence and betrayal. Akalaitis set it at a rehearsal table, with a narrator on hand to read the stage directions, but the doomed love triangle still boiled with energy: Bruce MacVittie desperately tried to maintain some dignity, while Paul Lazar was both hilarious and vile as the albatross hanging around Wendy vanden Heuvel’s neck. Both bitesize plays were bitter … but delicious.

5. I Am Sending You the Sacred Face

Joshua William Gelb’s Theater in Quarantine is a project designed for what’s surely the smallest theater in New York — his own closet, painted white, with only himself as actor and director. (His collaborator group is wide, though, a New York rogue’s gallery of experimental makers and designers.) TiQ’s last show of 2020 was the venue’s greatest: composer Heather Christian’s 40-minute opera about Mother Teresa, in which Gelb lip-synced to her haunting neo-gospel songs, while dressed in a spangly drag version of the saint’s (trademarked) outfit. “Man dresses as nun in cupboard” was certainly not on my prediction list for “show most likely to crack me like an egg,” but there I was, sunny side up on the floor. I Am Sending You the Sacred Face is as beautiful a cause for meditation as anything in the Book of Psalms — and as worthy an object for devotion.

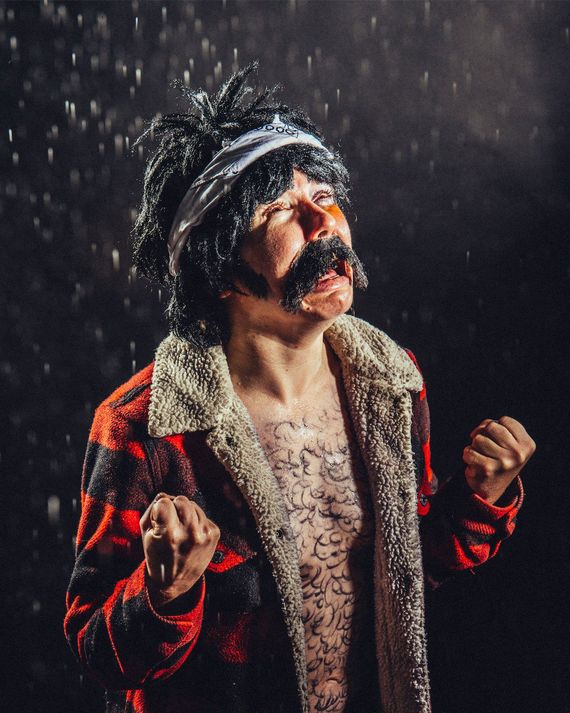

4. NATE

Before it was a special on Netflix, Natalie Palamides’s gonzo comedy show about consent was a live production, and not to brag or anything, but I saw it. [Buffs nails.] Palamides’s drag dude-bro creation Nate — hairy chest, La Croix-chugging tendencies, brush mustache — even more dangerous in person than he is on TV, where the performer can’t actually make you participate through the screen. Palamides is one of our great clowns, and Nate’s transgressive humor, genuinely curious attitude and ribald innocence are always hilarious and needling, no matter how you encounter it. But no mere streaming service can recreate the nervousness of impending audience participation, knowing that Nate’s questions about sexual boundaries might find you. Someday, Netflix will figure out how to zap that electric combination of fear, excitement and pre-humiliation directly into our lower guts; until then, you’re going to have to go to the theater.

3. The Seagull on The Sims 4

Celine Song’s adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s beloved play took place over two nights on Twitch, using the open platform of The Sims as her theater, repertory company, costumer, and collaborator. While hundreds watched from the chat stream, Song prodded her game-created avatars into approximations of the play’s love matches, breakups, and even deaths. It was a show, but also an education, as Song chatted about her craft while demonstrating it. How does a playwright build a world? How much of stage realism is just a certain level of complexity? Will Sim Masha have her dang baby? (Answers: while laughing; a lot; no.) The audience experienced the thrill of creation, even though we were just kibitzing. And when Song had her playwright friends call in, it felt — a bit — like breaking free from isolation and joining a community of writers that stretched back to Chekhov’s own day.

2. Paris

Eboni Booth’s superbly unnerving period portrait of a woman getting a job in a big-box store sometimes tastes like drama (a boss and employee bond over the unease of being a Vermonter while Black), sometimes like “that’s so ’90s!” comedy (the store’s break room fills up with various appalling haircuts), and sometimes like the sheer, unadulterated horror that comes from at-will employment. Tonally, Booth’s play exists comfortably on a razor’s edge, which meant it kept drawing blood as you handled it. Director Knud Adams is always fastidious, and here his icy perfectionism exactly matched the writer’s cinematic naturalism: It was so rich in detail, audiences could feel the Vermont cold from their seats in New York. The performances were also all stupendous, and I dream that this production might return after the shutdown. Our year of big-box retailer super-dependence has only sharpened its relevance.

1. Dana H.

Nothing in Dana H. follows the usual rules of dramatic construction — the credited playwright Lucas Hnath didn’t write it (the entire text is an interview with his mother, Dana Higginbotham), nor is the actor onstage speaking it (the radiant Deirdre O’Connell lip-syncs to Higginbotham’s recorded voice). In the rubble of theatrical convention, though, stands something illuminating, humanist, courageous, tragic. Higginbotham recounts a terrifying abduction that stretches our credulity, then points out that exact wry disbelief — from cops, from family members — is what left her so vulnerable in the first place. Dana H. achieves the height of theatrical craft and then leaps far beyond it to some quality more like witness or testimony. Scholars will write dissertations on it; someday, it will reorder our understanding of performance. But in the meantime, it stayed busy shattering the present world, one reeling audience at a time.