This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

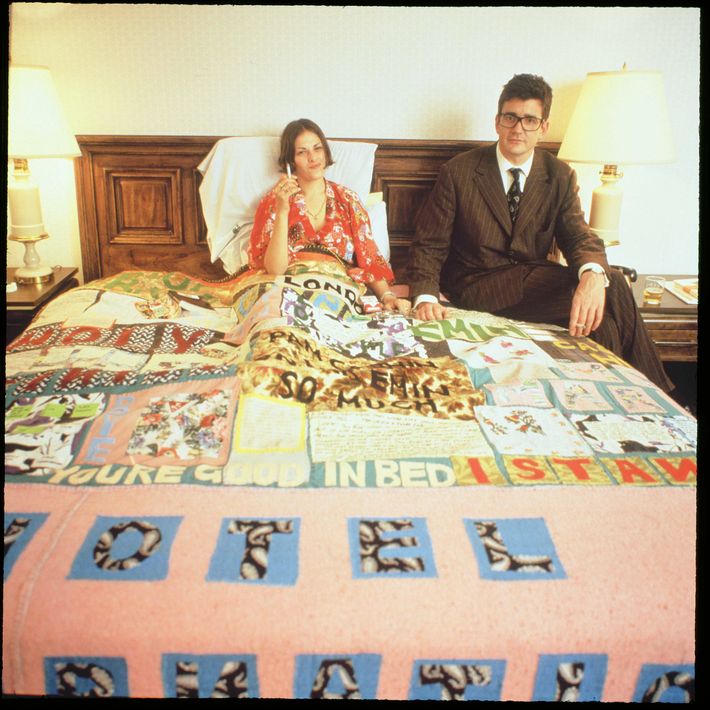

The first time I laid eyes on Tracey Emin was in 1994 in a wee suite of rooms in the former Gramercy Park Hotel. She was part of what was known as the YBAs (Young British Artists), who had invaded the New York art scene in the mid-’90s, and made her U.S. debut at the Gramercy International Art Fair, the indie edition of what ultimately morphed into the gargantuan Armory Show. Emin, a vision of power, passion, nonchalance, and abandon, was smoking a cigarette in bed, lounging under a quilt that had the names of family members, diaristic recollections, and places she’d lived sewn onto it. She had the presence of an artist casual but half mad with determination.

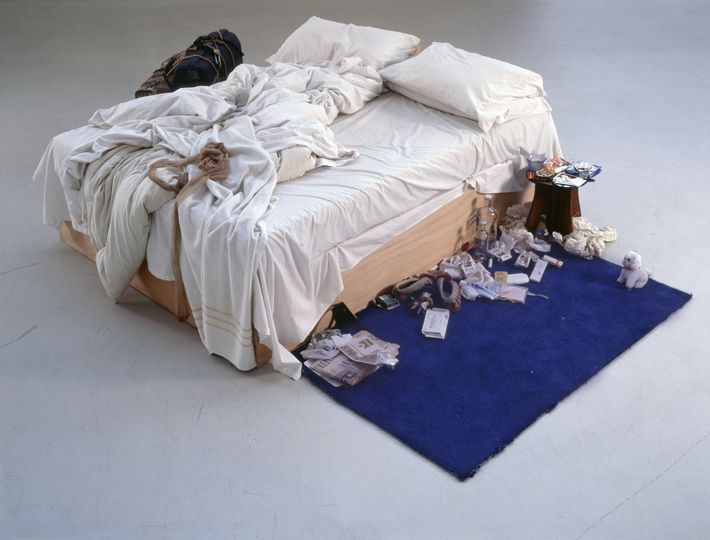

Emin would go on to become a legend in her native England but never caught fire here in the same way. She was so far out in front of all curves that her installations like 1998’s My Bed — a re-creation of a disheveled bed with clothes and condoms strewn about, a statement on love and loss that offended just about everyone — and her ecstatic, tragic paintings were misinterpreted as opera buffa, shock-your-nana art, as if she were a messy female version of Damien Hirst. But she is a great artist who does it all: neon, drawings, prints, and sculpture, often featuring women in poses of abjection, self-abuse, and self-pleasure. And she only gets better with time, even after going through a horrific bout of bladder cancer. After radical surgery three years ago, she must now wear a urostomy bag and suffers from chronic backaches and urinary-tract infections. Her colon keeps collapsing because there is nothing to keep it in place. When that happens, the pain can be excruciating.

We began DM’ing on Instagram during the pandemic and shared our cancer stories — hers and my wife’s. Last year, we had a conversation onstage at the New York Academy of Art; recently, we connected again over the phone on the occasion of her upcoming show “Lovers Grave” at White Cube in New York, the gallery founded by her longtime dealer, Jay Jopling. When we speak, we never speak about the future. Only the now. I asked Emin how she was feeling about her work, and she compared it to doing cross-country running as a teenager. “I could run really fast at the end, and I’d always come in with a really good time,” she said. “I see my art career and my life like that. I think that I’ve just been slowly jogging along. Now, I’m coming to the end, I’m coming to the school gates, and I’ve got to sprint and go hard. That’s one brilliant thing: When you’ve been seriously ill and you come out the other side, you really don’t fuck around anymore, ever.”

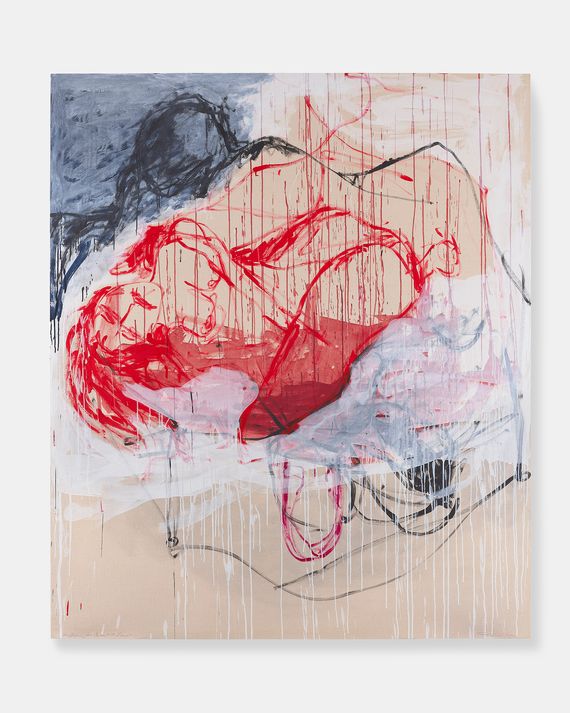

This new cycle of paintings — they’re very personal. They’re about your love life. They’re about abandonment, death, and joy. They also seem to have a sense of redemption, of deliverance.

If you have a passionate love affair, it’s beautiful, but it’s also sort of tragic. You know in Pompeii where you have the two lovers that are curled up together and they’ve died in the ash cloud? It’s this idea of being together for eternity. That’s why these paintings are called “Lovers Grave.” It’s a place of joy and love and forever, and also it’s a promise — a promise to the next world, I suppose. This work is a pouring out of my soul. Since I was ill, that’s become more and more important to me because we all have a time limit. Because I’ve been given the extra time, I mustn’t fuck up. I have to have this clarity about why I’m doing something. There can’t be any ulterior motive. It can’t be because I want to sell a painting.

And the paintings tell you more than you know, don’t you think?

It’s like going to a fortune teller. I spend a long time thinking about them. Sometimes I get scared to touch them — it’s like the painting has its own life and its own way of breathing and living.

But it’s also you. There’s this beautiful long-legged woman in these images. Sometimes she’s a dominant figure, sometimes she’s curled in a ball, other times she’s in ecstasy.

Yeah, well, it’s me. But I never use a mirror. I never use photographs. Some of the drawings of myself aren’t very good — they’re not very academic. Sometimes they’re very good. It all comes from my mind, like a cavewoman’s drawing.

How do you feel about showing in New York right now?

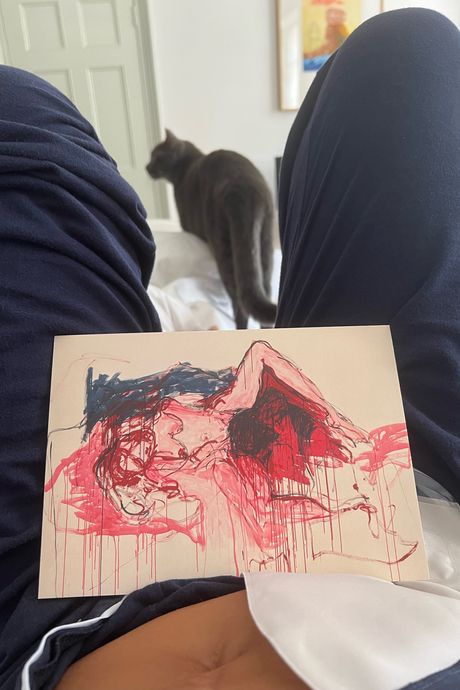

Really excited. I just got the hard copy of the private-viewing card. I was sitting in bed looking at it this morning, and I actually squeaked. I was thinking Rothko, I was thinking Pollock, Truman Capote. I haven’t thought like that for a long time about New York. And it’s not just for me — it’s for Jay. We are both 60. I’m thinking, Fucking hell. This is a culmination of 30 years.

And it all started around the time of the show at the Gramercy Park Hotel.

At that time, I felt that my art career had no importance whatsoever, was never going to have any importance. I’d had a show at Jay’s and called it my major retrospective because I thought it was the only exhibition I was ever going to have. It was compiled of images of all the work I’d ever made, tiny, little images printed on photographs and then made into badges and sewn onto the last piece of canvas I had to make a painting on. I knew about all this sentimentality to do with it, but nobody else did. That’s because it really wasn’t fashionable in 1993 to be sincere.

Then the reception of your work got thrown in with something called the YBAs, who piled irony upon irony. In you, I saw somebody who was incredibly open, honest, and vulnerable. But somehow you got lumped in with them.

I didn’t get lumped in exactly — a lot of those people at that time were my friends, and I was having a relationship with Carl Freedman. Also, me and Sarah Lucas had a shop together. I had a longtime relationship with Mat Collishaw. Jay showed a lot of the YBAs at the time. So even though my work wasn’t part of all of that, I definitely was. I had a big personality and I liked to party and the YBAs definitely liked to party. Unfortunately, that is what we got a reputation for instead of our work. I always get upset because I have zero career in America, but then, looking at the perception of me in the ’90s, I’m not surprised: Oh look, here comes the drunk party girl in the cowboy boots.

What impact do you think that had, especially in the United States, on the reception of your work?

I haven’t got what it takes to be a successful artist in America. I haven’t got those kind of balls, and I don’t want them. They’re too macho, they’re too big, they’re too baggy. They drag on the floor when you walk, right? My balls are up here on my chest, close to my heart. I just couldn’t hack it. I’m really happy with the way things have turned out. I wasn’t maybe five or six years ago. Now I’m really content with my work, how people perceive me. Also, I’m sitting here saying I’m sorry. I’m sorry for the way that I behaved. I’m sorry that I didn’t let you know how serious I was about art. I’m sorry that I looked irreverent, like I didn’t care. I care more about art than anything in the whole world. Maybe I was hiding it from everybody because I was scared of being rejected.

That’s how I fell in love with your work. I saw a painting in the early 2000s of a woman, a figurative painting. I felt like I was hearing thoughts I shouldn’t hear about what women think, feel, go through. I’m seeing it much more in art these days, but at the time I was astonished at it.

Things have changed a lot for me thanks to the Me Too movement and people having much louder voices. Whereas 20 years ago people didn’t. A lot of my work was not about me; it was about women like me. It was people of my class and background. It was people of mixed race like me. It was people who had suffered poverty as a child like me. It was people who had been raped like me. It was people who had had two abortions and one that went terribly, terribly wrong. It was people like me who had been sexually abused as a child. It was people like me who had not been abused but had loads of teenage sex. I was making work about this stuff, and they go, “Oh my God, she’s moaning on about abortion again. She going on about rape.” Yeah, fucking right I’m going on about rape because a girl shouldn’t be raped when she’s 13. Where I grew up, when you were raped, you would go to school the next day and someone would go, “Oh, what’s wrong with her?” and they’d go, “Oh, she was broken into last night.” That’s how it was referred to.

I made work about this, and you know what? People didn’t like that I made work about that. Because no one wants to admit that these things happen. Nobody wants to admit that an 8-year-old gets sexually abused either. Nobody wants to think about those things. But I make work about those things.

When do you think you knew you were an artist?

I’ve never done anything else. Nothing at all. I had a couple of part-time jobs. Like, I was so broke until the late ’90s. To me, money never mattered. All that mattered to me was that I was an artist. I never wanted to do anything else. I left school at 13, then got my art degree when I was 23. Academically, I had this big void in my mind, this big chasm of space that could just take in as much art as I wanted and as much visual interest as I needed. After I left art school, I did a two-year, part-time course in philosophy. It was just brilliant. It was like, because my brain hadn’t been filled up with loads of shit from school, I had all this room to take in whatever I wanted.

Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch were the first artists that I really fell in love with, around 13. At school, we had learned about Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, so that’s what I thought art was, which was cool, in a way. But then when I discovered Schiele and Munch, that was my art. They were my friends.

You just had a show with Munch in 2020 at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, where you selected some of his work to show alongside yours. I think you two share a great, deep sympathy for women. How do your women and his women connect?

Munch wasn’t just painting women — he put his own emotions and his own guilt, his own failures and his own admissions of everything into that work. Once there was a New York art historian who was interviewing me for a catalogue in my studio, and I was sort of laid out on this daybed with my hand like this, with my knee up like that. He said to me, “You’re so obviously influenced by Matisse’s cutouts.” I went, “No, no.” He said, “It’s quite obvious you are.” I went, “No, it’s not obvious I am.” He said, “All your figures are just like that with the leg up and the arm back.” I lay there on this couch like a Matisse and I said, “What do you mean? Like this? This is my body, this is me. Are you telling me that I’m influenced by Matisse because I’m lying like a Matisse figure? Are you telling me that I don’t own and control my own body?”

What’s quite interesting about Munch is Munch put himself in the picture. Munch really adored and loved women but not as a muse like Picasso or other artists. He liked them as a kind of emotional springboard. He was very open about his jealousy, his fears, his guilt, his vanity, his fear of aging. For me, Munch was so honest and so cool, as an artist and as a radical. Imagine: In, like, 1890, he’s using lime green, cerise pink. He’s painting these crazed-up images. He’s really expressing his emotions at a time when men didn’t express their emotions — when no one expressed their emotions. Munch is like my kindred spirit.

That Munch show was when a lot of people found out you had cancer.

I was doing an interview with the Sunday Times, and the journalist came to see me. She came to my house and I was in bed and she came upstairs. It was about midday or something and I was in bed, and she said, “Oh, late night, was it?” I said, “No. Cancer.” It was a moment I’ve always been waiting for. This journalist went, “Oh my God.” So we talked about that then. When she wrote her preview of my show with Munch, I was all across the news. I was thinking, My God, imagine what would’ve happened if I died. In Britain, it’s really weird: It’s not even like I’m an artist. It’s like I’m sort of a mascot, like a national treasure of sorts. The last thing they would want is for me to drop dead. But I think I was really lucky with the cancer, the fact that I had it during lockdown, because I didn’t miss anything. Then the other thing is no one missed me because everybody was missing each other. I could be really ill and nearly die in private and then come back to life in public.

How did you find out you had it?

It was lockdown, and I was on the roof of my old house. It was a very Mary Poppins type of situation; I was sitting on the eaves of the roof, naked, and my neighbor, the vicar, was below me having a tea party. I was drinking Champagne, and I stood up with my glass and said, “Hello, Vicar.” He couldn’t see me. I thought this was so amusing. I was thinking, God, I’ve never been so happy. Then I went to the loo and there was blood everywhere.

I went to my gynecologist next day and told her about the blood. She checked me out and said, “What’s that?” She had a mask on because it was COVID, but her face was in so much distress. Within three weeks, I was having my bladder removed, my ureter, my lymph nodes, half of my vagina, part of my bowel, and, oh, some other bits and pieces. I didn’t really have time to think about it all. My surgeon, he said to me, “Look, these are the side effects: You’re going to lose about 30 pounds. You’re going to have part of your vagina removed, so your vagina’s going to be really small.” I said to him, “Excuse me, are you saying these are bad side effects?” My friend who was with me, Cecily, she’s going, “It’s not funny.”

There had to be another surgeon that comes in to give me a second opinion. I went, “I’ve got one question.” He goes, “What is it?” I said, “Can I get a dog?” He said, “Why are you asking that? No, you can’t.” Then, when he left, I said to my surgeon, “There’s a really good chance that I’m going to die.” He said, “Yep, there is.There’s more chance of you dying than living.” I had probably six months to live if I didn’t have the surgery immediately. When you are faced with that, life changes dramatically. Apart from the vagina and the bladder business, which is a bit annoying, the cancer thing is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me because it was like the biggest kick up the backside that anybody could ever have. I’m not comparing myself to Warhol, but when Andy Warhol was shot, he came out of hospital and there was no messing around after that. He got a desk, he got a suit, he cleaned up his whole act, everything. He became so focused. It’s a bit like me since the cancer.

My wife and I have been through cancer stuff, and this is what we talked about, writing through it. That our work was really all there was.

I worked right up until the surgery. Then, after the surgery, it was impossible. I couldn’t even pour a teapot. I couldn’t carry anything. I couldn’t walk. I was about six months in bed, really.

But now you are working again.

I’ve got a studio in London, my studio in Margate, and a studio in France, but I haven’t been to France for a long time because I’ve been so ill. But my studio in Margate is really big. And I have these giant canvases all the way around and it’s really spacious with the most amazing light. I still do this terrible thing: I can do a really good painting and it’s perfect. Then I go to bed and think, Oh, I’ve got to change that bit, and in the morning I change it and completely destroy it. I’ll paint over it just as it’s going out the door to be hung. Harry Weller, who’s my creative director, would take a photo of the painting because he knew that when he turned his back, I would completely cover it. I can do what I call a very good Tracey painting, and I know someone’s going to want it and hang it on their wall, but I don’t want it and I don’t want to hang it on my wall. I can do a really bad, crappy, shitty, crazy, mad Tracey painting and no one will want it on their wall, but I want it because it’s the most interesting thing that I’ve done for years. It’s made me think, and it’s made me question everything. It sparked something from my childhood or it scared me.

The other day, I did a painting that scared me because there were these dead people in it. Me and Harry could see the dead people, and it was like, “Fucking hell. They’ve come back.” With painting, it’s so hot. I’m so serious about it. It’s because the painting has become an entity. It’s become a sort of spirit that lives outside of me and joins me sometimes. I don’t care if anyone thinks that’s crap or bullshit. It’s not. To me, it’s real.

I would like to tell every American museum, “Tracey Emin is a great subject for an extraordinary exhibition.”

Can I say something about museum shows? In 1995, I was in this group show called “Brilliant! New Art From London” at the Walker Art Center. I showed my tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995. The people at the Walker asked me what I needed for my tent. I said, “Silence.” I needed quiet and contemplation for people to go inside the tent and read it. Then, when I go to the Walker, they stick my tent in the middle of the fucking motorway. It was hideous. I said, “I can’t put my tent there.” And Richard Flood, a curator, said there was nowhere else to put it. When I saw it had been moved up to another floor, I left the building and pulled it down the stairs and the tent went boink. He said, “Where are you going?” I said, “To my hotel.” He said, “You can’t take that tent out of this building.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Because it’s insured.” I went, “No, it’s not, because I carried it here on the plane,” which I had done. Then Richard Flood, in front of a lot of people, shouted at me, “With your attitude, you’ll never show in a museum in America again.” I said to him, “With your attitude, I don’t fucking want to.” Guess what? I haven’t.

You’re running an artist residency and school in Margate. How did that come about?

I’ve somehow accumulated a massive property portfolio because I love property, because I’m scared of being homeless, because I’m scared of my friends being homeless. I’ve been homeless three times in my life. When I say homeless, I mean twice with my family and once alone as an adult. My mom’s family were Roma from England — we’ve always done seances and palm reading and fortune-telling. When I was little, a fortune teller told me I’d be really well known and famous for what I did and I’d be phenomenally wealthy. I wouldn’t be wealthy because of what I do but because of property.

So all the time with art, I saved money, saved money, saved money. I bought my first house in 2001. At the same time that everybody was doing coke, I was paying my mortgage. I’m frugal. I’m not gauche or flash. I’m always saving and diligent. Now I’m really, really comfortable and I have everything that I need, but I still love property. I bought a really big old bathhouse in Margate and an old morgue. I’ve turned the bathhouse into a studio complex and an art school and the morgue into a training kitchen for restaurants. Last year, we had 750 applications for ten residencies from people all over the world hoping to move to Margate. When a painting of mine sold at Christie’s for £2.3 million, every single penny went toward the school and the students. I’d like to own a Munch, but I’d much rather give lots of artists the chance and a facility to make art and become artists and be more confident within their own practice.

You’re still working with Munch anyway: Last year, you unveiled a mind-boggling sculpture outside the Munch museum in Oslo called The Mother, an enormous female figure.

Yeah, it’s nine meters high. You can see it from a plane. It’s bronze, and it’s of my mum, -ish. It’s like everyone’s mum. Her legs are open, and there’s a beautiful garden in between. She’s a figure of a really old woman. People were nasty about it because she doesn’t look attractive. I said, “Well, isn’t your mom going to get old? Isn’t your wife going to get old? Your sister, your lover, your daughter? Women get old.” Everywhere, you see so many images of old men that we have to respect, the father figures of society. But you never see women in the same way, primal, real women.

How are women doing in the art world these days?

Well, I think women are doing a lot better than men. Men peak between the age of 40 and 50, and women peak between the age of 50 and 80. Men have one big giant ejaculation, and women come and come and come again. So this is why if you are a female artist and you’re doing okay at 50, you’re going to be doing quite good at 60, fucking excellent at 70, and out of this world at 80 and 90. One of my first and best artist friends in New York was Louise Bourgeois. There were 50 years between us, but she was a big inspiration because there she was, 97, still going for it, still cracking it out, still thinking. If I can be like that, it means I’ve got only halfway through my career.

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave opens at White Cube on November 4.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’