As told to Jennifer Vineyard

I was born in 1958, and the Velvet Underground disbanded in the early ’70s, so I was aware of the Velvet Underground as a young kid. I remember finding the banana LP at Sears, because you’d buy records in places like department stores. It wasn’t until later I found a record store in New Haven, Connecticut, called Cutler’s, where we’d find records that were more obscure. You would see them written about every once in a while, either in Rolling Stone or CREEM or the magazines of the time, like Circus, Hit Parader, and Rock Scene. Rock Scene was the most important one because it was primarily events that were happening in New York City. They would have all the heavyweights in there, like Led Zeppelin and David Bowie, but they were also covering what was going on in the margins. That was really exciting, wondering what was going on in these little clubs in New York City, because the people just looked fabulous, and the music sounded more intriguing than what was going on at the time with youth culture, which was sort of a fallout from hippie and post-Vietnam kind of vibe. At that time, the hip thing was going back to the country, escaping the city and smoking pot with Joni Mitchell and David Crosby on the porch with the dogs. And there was all this music from Europe and England that had more pomp to it, like prog rock—Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. So to me, seeing images of Patti Smith standing on the subway platform—all of a sudden it was like this new idea that it was kind of cool to be urban. And that was like our new definition of identity. I wanted to investigate that. The reality of it was the city was destitute, and it became this kind of postapocalyptic landscape for artists, and there’s something very enchanting in that. I ran to it. I wanted to see Patti Smith.

Connecticut was a great place to be, because the bands would come to you. But I was very curious about going to New York City, to Max’s Kansas City. So as soon as I could figure it out, I drove to New York City and sought out Max’s Kansas City. I knew it was on Park Avenue—which is a very long avenue, by the way! So I drove along Park Avenue, and I yelled out the window, “Where’s Max’s?” [Laughs.] I eventually found it at the very bottom of the avenue, right near Union Square.

It was Suicide, the Planets—and the first band was the Cramps. I don’t know if subdued is the right word, but they weren’t as demonstrative as they became. They didn’t have their first seven-inch out yet, so nobody knew anything about them. They were just playing old ‘60s garage-rock covers for the most part. The whole fascination with garage rock that became part of punk culture wasn’t really there yet, so no one knew what these songs were, these spindly American lost gems of garage rock. And we were just like, What is this?! This is not … This really is not Pink Floyd, at all.

And then Suicide came out, it was just those two guys doing this completely assaultive performance noise rock. It was loud and pummeling and hypnotic and scary. Alan Vega would walk out on the table, wrap his microphone cord around audience members’ necks, and scream in their faces. Everybody was basically barricading themselves behind the tables at Max’s, so this lead singer would not attack them. It was that violent! And weird! I was also really interested in Richard Hell, because in New York rock magazines, Richard Hell just looked so fantastic, with his short hair and his bug-eyed stare. There was a little ad for his first seven-inch, which I ordered. I loved that seven-inch, “Blank Generation.” He wasn’t doing anything, and all of a sudden he was back with Richard Hell and the Voidoids, and that really excited me. I just knew at that point that I was in New York City. It was the sound of downtown New York. Everything about it aesthetically was what I wanted. I wanted that in my life. So I just moved to New York.

I moved in on South Street in ’76. I found my own place in ’77 on East 13th Street. Kim [Gordon] moved out to New York with Mike Kelley to do art, and she also wanted to play guitar and do expression with music, even though she wasn’t musically trained. Neither was I, for that matter. It was about creating your own language on the instrument that had all this tradition to it, without denying the tradition. But the technique of the tradition wasn’t necessary for you to create. And that was so liberating and exciting and wonderful and beautiful, and there was no ambition about it. All the artists were really involved with what was going on in the music scene. It was really cross-discipline there, as far as the visual artists and the music went. We thought the Ramones were as much of an art-rock band as the Talking Heads were. Punk rock was an artist’s music, even though it was sort of expressing this reclamation of rock and roll as a people’s music. It was a music for artists to call their own! The whole multidisciplinary artistry was key, but the energy was in the clubs. Like at Max’s Kansas City. And then CBGB was like this new clubhouse with the stucco exterior and the dilapidated awning outside. I always felt like I was walking into this magic witch’s gingerbread house there, because it was unlike any other New York building. It had those wooden swinging doors, and the crooked floors, and it was falling apart. CBGB was one of the last remaining authentic saloons from the Bowery of old. It had flophouses on each side for Bowery bums. The fact that Hilly Kristal left it intact was really wonderful. It was full of ghosts and memories.

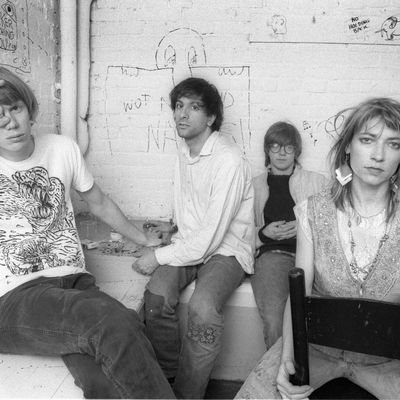

Kim and I were introduced by a mutual friend of ours. She came to see this band that I was in called the Coachmen. We were very influenced by the Velvets, Talking Heads, and the Feelies, and we were playing at Giorgio Gomelsky’s place in the 20s. She came to one of our shows, and we talked and talked and talked. I moved in with her on Eldridge Street because I was being ousted from my $110-a-month apartment on 13th and A, which I couldn’t afford to pay. I think she was paying maybe $200 or $300. It might as well have been $2,000 or $3,000, because I didn’t have any money. Nobody had any money. Every once in a while you could pay your rent and buy cigarettes or something. At the time, it was like, What are we going to do about food? What are we going to do about cigarettes? There was a lot of anxiety, but at that age, it doesn’t really manifest itself, because you have the whole world ahead of you. I asked Kim to play on this thing that I was starting to do. I knew Lee [Ranaldo] from a couple of other bands, and I asked Lee to play with us, because I thought he was really interesting and we really connected. We called ourselves Sonic Youth and our first gigs were at the Kitchen.

Kim introduced me and Michael Gira of Swans, and we became fast friends. He had gotten this windowless place, way east on 6th and B, and at that time it was a war zone. He had this little hole-in-the-wall place, and you could play in there as loud as you wanted, because as long as you were no louder than the gunshots outside, then you were kind of okay! We would just play all the time, and that was really where we developed our sound as a band.

I was interested in the Velvet Underground primarily as a band that wrote great songs. For me, the real experiment was the song structure and how lyrics lay into the music. As far as focusing on the guitar and its alternative tunings, that came out of experiencing really early Glenn Branca performances at Arleen Schloss’s, a space on Broome Street. I remember first seeing one of Glenn Branca’s six-guitar pieces, where each guitar had these single-note tunings on all six strings. So one guitarist would be in E, and one guitarist would be in A. And it just floored me out the window! It was really ferocious. It was beautiful. It worked on so many levels for me as rock and roll. It got me into places intellectually with New York music that was really, really important, not just to me but to Sonic Youth.

We employed a lot of alternative tuning in our music immediately. Glenn lent us a bunch of cheap thrift-store guitars that he had. I remember him bringing over three or four of them, and they had shaved-down necks and were already tuned to these weird tunings. I remember sitting down going, “Oh, great! I’m going to write a thousand songs on this.” I would stick a drumstick behind the 12th fret, and bang on it, and it sounded wonderful. “Well, there’s a song right there!” Lee was sticking a contact mike on a power drill that he held in his hand and sent it to his amplifier. “That’s another song!” It was so much fun. It was a lovely time. And it was completely in the lineage of New York music in existence. I immediately felt like that was my world.

*This is an expanded version of an article that appeared in the March 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.