It’s been just under a year since I last interviewed comics writer Ales Kot, but the shaven-headed Czech seems noticeably more mature now. He’s still one of the comics industry’s most-buzzed-about young guns, but rather than raving about the revelatory power of hallucinogens, he’s more into discussing prison reform. He’s still creating comics that are challenging and unconventional, but instead of tales about spies and Marvel superheroes, he’s doing indie work about race, class, and torture.

The 28-year-old Kot’s transformation isn’t surprising, as he’s had quite the year. He’s suffered from a debilitating bout of Lyme disease. Just as he was becoming one of Marvel’s biggest up-and-coming stars, he took a leap of faith and quit the company after wrapping up an acclaimed 15-issue run on Marvel’s Secret Avengers (which was more about PTSD and Jorge Luis Borges than capes and battles). He also said good-bye to his surreal creator-owned espionage series Zero — with a truly baffling, Lynchian final issue — and has his sights on turning it into a TV series. His Twitter account has become a battleground, where he takes on the comics industry for its glorification of the military and exclusion of nonwhite creators. And, like so many self-searching New Yorkers before him, he’s pulled up stakes and moved to Los Angeles.

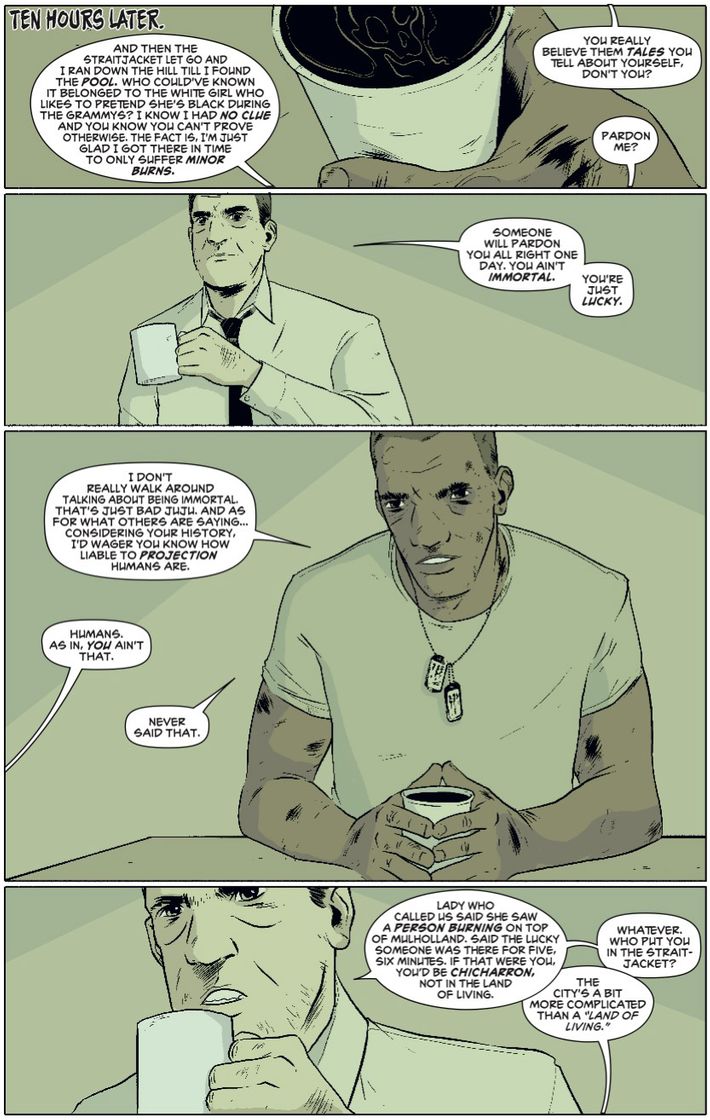

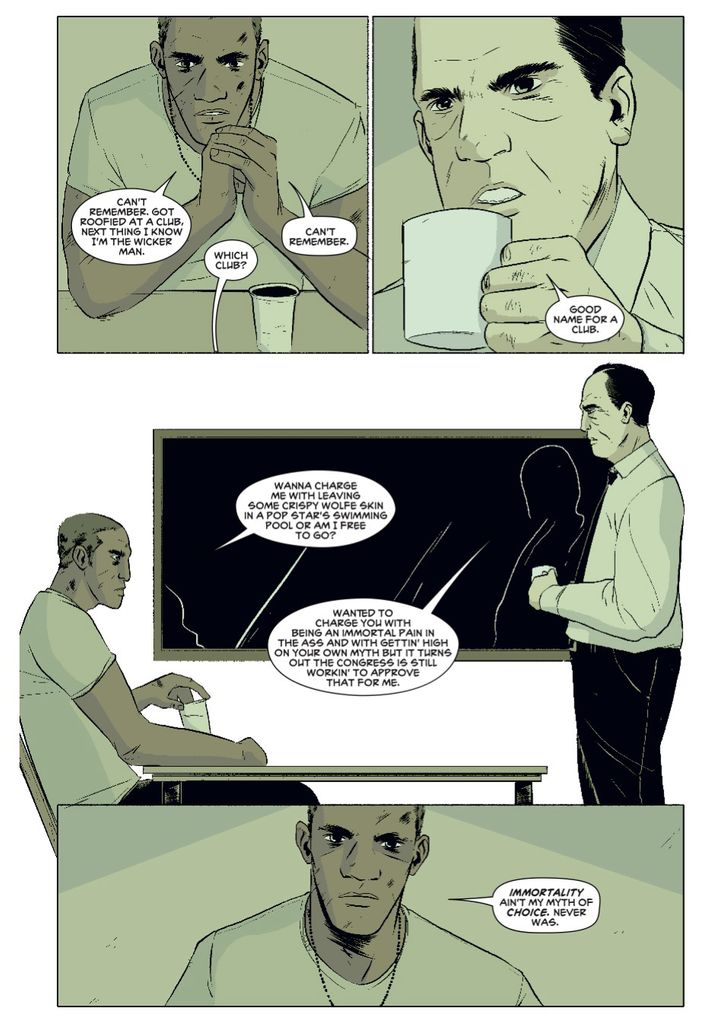

That city is the overheated, rapidly beating heart of his new series, Image Comics’ Wolf. It launches this week and follows the strange exploits of Antoine Wolfe, a soldier turned paranormal investigator who probes the mystical underbelly of L.A. Below, we’re exclusively unveiling the first five pages of it.

It’s some of his most confident, consistent work to date. Kot’s already two issues into his other Image series, Material, a splintered narrative about a disparate group of people who may or may not be on the verge of experiencing the world’s first artificial intelligence. That series also feels like a kind of autobiography, in that the story is heavily annotated with supplemental reading about technology, police brutality, and everything else that’s on his mind these days. He and I caught up to talk about legalized slavery, ghosts, and his no-holds-barred criticisms of “institutionalized racism and bigotry” in the comics industry.

The L.A. setting is essential to the story you want to tell with Wolf. What inspired you to turn your attention toward Hollywood?

Wolf is completely Los Angeles– and California-specific. Setting the story anywhere else never even crossed my mind, I believe. There are parts of the story, if we go long enough, that lead us to other places — New Orleans and the Goldman Sachs headquarters in Manhattan, where the top executives conduct unspeakable rituals to keep their … again, spoilers, but you get the drift.

Los Angeles is the first place I lived in America. I came for three months and stayed for four years, then moved away for two, now came back. It feels like home, and I know this place. Wolf is primarily about a suicidal, troubled paranormal detective and a young girl in deep shit, but it’s also equally true to say Wolf is an exploration of myths and what they mean, and an exploration of Los Angeles and California. Something was calling me back.

I love this land. I love this place. I am also aware of its deep history, which is often dark and still unresolved, with issues such as the Native American genocide, slavery, racism, government corruption, and a toxic prison-industrial complex that’s barely acknowledged in public discussion, much less worked through. Wolf is one of the ways I want to contribute to the discussion, because to stay silent in face of injustice is to be violent.

There’s a seemingly obvious antecedent to Antoine Wolfe: DC’s working-class paranormal investigator John Constantine. What’s his thematic relationship to Wolfe?

The tagline for Wolf is “Blood and Magic,” and John Constantine is the most famous street magician in comics; the kind that bled nearly always. I read the original Hellblazer comics with great interest. They inspired me because they were highly entertaining, unafraid of getting dark, and unashamedly political. As a depressed, suicidal teenager, I sometimes identified with John Constantine’s depressed, near-suicidal existence. He knew more about the nature of the world than most people around him — and growing up in the highly industrialized and poor corner of the Czech Republic, coming from a family that was falling apart due to decades of damage and lies, in a landscape equally beautiful and poisoned, I felt very much the same. I also liked Constantine’s stoicism in the face of danger, and it inspired me to adopt a similar attitude. The ultimate secret of magic, after all, is that anyone can do it.

Unfortunately, when it comes to art (and entertainment), corporations often impose restrictions that go against the exploratory nature of art (and entertainment). Related to that is another nugget of obvious wisdom — the political and the corporate rarely mix well, and when a big corporation owns John Constantine as a character, it means a huge element of what made the series resonate in the first place will likely vanish. All of which contributed to me thinking there’s a need for a new street magician in town. Hence, Wolfe.

A recurring motif in your work is the significance of character names—naming people after authors whose work deals with relevant themes, and so on. What’s behind “Antoine Wolfe”?

If I dug into that I would spoil a lot, so I’ll just give a hint: First name points to Louisiana, last name to Germany. Considering Antoine’s African-American, it’s a potent mix of genetic ancestry. Plus, we’re talking about a book that has werewolves in it, so … I say no more.

You caught heat for tweeting about how the comics industry needs to shunt off its adoration of the military and be more inclusive of nonwhite creators. What sparked those tweets?

The world around us sparked them. We could talk about the problems inherent in [Punisher artist] Mitch Gerads supporting — maybe unwittingly — the twisted legacy of serial killer Chris Kyle or the problems of racial depiction in Strange Fruit No. 1 [Note: Strange Fruit is a controversial, recently released comic about the Jim Crow South, written and drawn by white men], but those are merely symptoms of a larger problem. Many superhero comics and films are perfect recruitment tools for the military-industrial complex.

Much of the comics industry is also nearly devoid of transgender creators and creators of color. This, I know for sure, is by no means just an accident. It is a symptom of centuries of institutionalized racism and bigotry. On a fictional character level, the situation is improving. On encouraging and hiring transgender creators and creators of color, we have to make big steps forward, and do so immediately.

The industry can improve by listening to criticism and marginalized voices, and by opening up spaces for nonwhite creators and transgender creators. The industry can improve by ceasing to be a gigantic circle-jerk where people pat themselves on the back for every halfhearted attempt at creating anything other than superheroes. The industry can improve if and when all the individuals who make the industry educate themselves and start following a code of conduct focused not only on monetary gain but also on a strong ethical stance. Mainly, all of this goes to the men in the industry, and especially all the white heterosexual men.

The industry can improve by Marvel and DC genuinely putting a serious effort into starting careers of young creators who have not already made their names at Image or Dark Horse or other places. Starting with Wolf No. 5, I’ll be opening the last pages of each issue for new creators of color. They will be able to come and make their own short story, own it, and get paid a part of whatever I make financially. Olalekan Jeyifous, Minhal Baig, Aaron Stewart-Ahn, [and] Darryl Ayo are the first few, and there’s plenty more already. Right now I’m also working with various sex workers who will likely be contributing a majority of essays for Material. Destigmatizing sex and the sex industry is something I hugely believe in, and I also believe it is my duty to do my best with the privileges I currently possess; not just for myself but also for my community.

Some people might blacklist me. Others already did. I also know that game recognizes game, and I believe that for every two places that close for me, ten new [ones] will open. Every year I level up. 2015’s no different.

A remarkable aspect of Material is how it incorporates the investigations that Guardian reporter Spencer Ackerman recently did about the Chicago Police Department’s covert use of brutality at a warehouse called Homan Square. How did that end up in Material? Have you talked to Ackerman about it?

I suspect I saw Spencer’s reporting mentioned on Twitter, clicked the link — nothing like having a curated feed full of people whose behavior you like, people you want to learn from — and went down the rabbit hole. Spencer and I started talking after I learned of his admiration for what we did with Material. Now he’s writing the foreword for the first collected edition, and I am deeply grateful for it. I admire his relentless, ethical, and brave reporting.

Material exists because I needed an outlet that would keep me sane. Everything I write is designed to be an act of self-healing and/or self-exploration in some way, but with Material I aimed for constant immediacy, a model that would let me confront whatever I needed to explore and write about right away. We live in an era where Bree Newsome gets jailed for taking down a flag that stands as nothing but a symbol of deep hate. We live in an era where cops kill unarmed black men and women with impunity. We are in an era where we live with the evil done in our names, and in the names of the countries in our passports. I want us to look into a mirror and face ourselves. I want us to say stop to that, and I want us to act accordingly.

So that’s why I put Homan Square into Material. I want us to face the horrors of what we do, and I want us to end them and transform them into something better, something that won’t be built on harming, arresting, and marginalizing people. Right now, America still runs on slavery. It just has a different name: the prison-industrial complex. It is our civic duty to confront and kill it.

Why end Zero where you ended it? The final issue was about as strange and impenetrable as a comic can get, with fungal infections talking to humans, bullets flying backwards out of skulls, and a cameo from William S. Burroughs.

Nothing else felt right. I don’t want to interpret it because there’s no easy interpretation that sticks completely, and that’s my perception of life: There’s always something just slightly out of reach, and it’s up to us to choose how we want to interact with it. Our perception involves not knowing. We know so little! We see roughly 3 percent of the electromagnetic spectrum and build sciences and approaches to life on it. We pretend we know but we lack the clarity. It doesn’t mean we have to stop hoping or believing, but it does bring up an important part of my daily life: learning to be comfortable with not knowing. Accepting the mystery.

What was your original pitch for Zero, and how did the idea evolve over the time of you executing it?

Original pitch: deconstruct and destroy the James Bond superspy archetype of bleak male force as a good thing for us all. Execution: The William S. Burroughs inclusion is the major part that took me by surprise. Well, that, and my dealing with Lyme disease and other infections, some of which were reflected in the comic book’s viral content. Pun intended.

Do you ever worry about being too “on the nose” when it comes to references to books, historical figures, social issues, and the like in your stories? You put them right in front of the reader.

Not really. I gotta do me.