The protests started almost immediately after the presidential election. An artist named Annette Lemieux emailed the Whitney Museum and asked that her installation Left Right Left Right — a series of life-size photographs of raised fists turned into protest signs — be turned upside down. The artist Jonathan Horowitz and some friends started an Instagram feed called @dear_ivanka, attempting to directly appeal to the soon-to-be First Daughter and shame her into pushing her father away from the Bannonite brink. The artist Richard Prince refunded her money for a piece that she bought, then put out a statement that was intended to de-authenticate it.

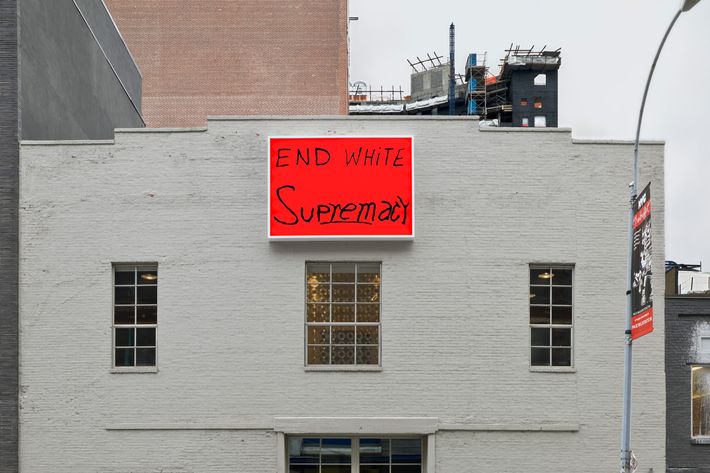

Sam Durant’s light-box sculpture, which read END WHITE SUPREMACY, was hoisted onto the façade of Paula Cooper Gallery in Chelsea (where it first appeared in the remarkably different context of Obama’s election in 2008), and another edition of it was set up by the gallery Blum & Poe to greet visitors at the Miami Beach Convention Center for Art Basel the first weekend of December, where the usual luxury-brand-fueled jet-set bacchanal seemed a bit muted and anxious and Nadya Tolokonnikova, founder of Pussy Riot, delivered a lecture by the pool at the Nautilus hotel on the dangers of authoritarianism.

As the inauguration approached, the art world’s desire to make a statement increased. Many museums across the country went free on January 20, which was seen as a more productive response than shutting down, as a movement called J20 Art Strike called for, and the Whitney did a day of programs in partnership with the group Occupy Museums. The Guggenheim planted a Yoko Ono Wish Tree on the sidewalk out front, letting passersby record their hopes — perhaps that peace and tolerance might prevail. A collective of artists started a platform called 2 Hours a Week, which connects people with political actions they can take while still holding down their jobs. Gallerist Carol Greene teamed up with artist Rachel Harrison to rent buses to bring a group to the Women’s March, armed with social-media-friendly signage.

And it hasn’t let up. Each Trump proclamation has seemed to inspire a new round of agitation and action. When the president announced the first iteration of his ban on immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries, Davis Museum at Wellesley College covered or removed about 120 works that had been either made or donated by an immigrant. The Museum of Modern Art hung work from its collection by artists who come from three of the excluded nations.

Establishment Chelsea gallerist Andrea Rosen decided to shut down her gallery, in part to focus on political activities. The anti-Establishment (or, anyway, far less established) Christopher Stout Gallery in Bushwick, which specialized in “feminist, queer, anti-Establishment, hyperaggressive, mystic and/or joyously sexual” art, rebranded itself the ADO (Art During the Occupation) Project. Awol Erizku, the photographer best known for having taken Beyoncé’s maternity portrait, just announced his “anti-Trump” art show “Make America Great Again,” at which he will sell baseball caps featuring that slogan superimposed on the image of a black panther (“to have something affordable in the show”). And the Public Art Fund in New York commissioned Ai Weiwei for a citywide proposition titled, with pointed irony, “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors.”

For the first 100 days of the administration, MoMA PS1 has given over a gallery to “For Freedoms,” a collaboration by the artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman for which they set up a super-PAC. The name was inspired by Norman Rockwell’s paintings of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech in 1941 and sought to co-opt the image of a simpler age, as Trump had. Last year, the super-PAC put up a billboard in Pearl, Mississippi, with the words MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN superimposed on the famous 1965 photo of civil-rights protesters on the bridge in Selma, Alabama, moments before state troopers unleashed tear gas and beat them with billy clubs.

The billboard is on display at PS1, its meaning having shifted after the election. Intensified. This happened often with artworks made in the run-up to the election; they just looked different afterward. Maurizio Cattelan’s solid-gold toilet, titled America, which was installed at the Guggenheim last September, suddenly felt spot-on. As did the punk-rock political caricatures in the Raymond Pettibon show at the New Museum. What might have been a quiet show of Alice Neel portraits of her multiethnic friends at David Zwirner became a rallying point of sorts for empathy. (See Cyrus, the Gentle Iranian.) The Dumbo nonprofit space Art in General’s eerie night-vision installation by the collective Postcommodity, whose members live and work near the U.S. border with Mexico, built around conversations the artists had with Border Patrol agents about how they use decoys to catch people trying to cross the border, now seems extra ominous.

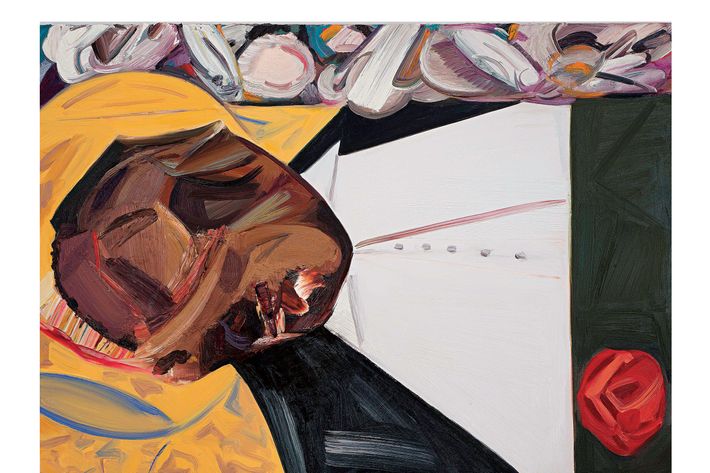

Most prominent of all is the Whitney Biennial (in which both Postcommodity and Occupy Museums have pieces), which was skillfully planned to map the various cultural currents of the recent past as embodied in art. But in these highly charged times, it went from being almost universally well received for its political engagement to being the center of protests when an abstracted painting by the white artist Dana Schutz of the body of Emmett Till was condemned as an example of insensitive cultural appropriation. That reaction would have happened anyway, more than likely, but it ignited into something more rancorous (enough so to end up being discussed on The View) because, right now, the art world is on a perpetual boil. Whether this ideological high alert will produce good art is one question; whether the art will do any good is another.

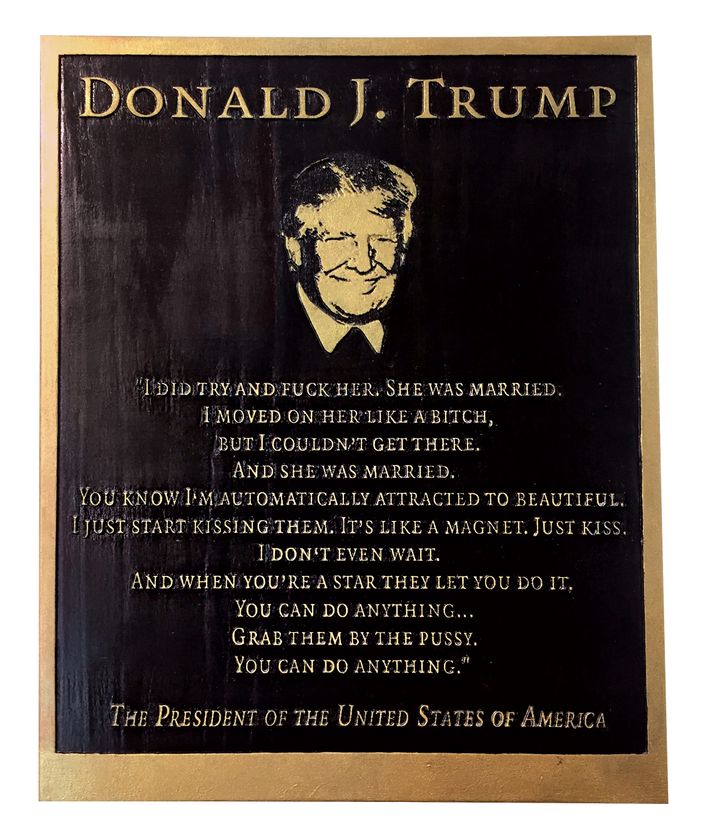

“The left,” says the artist Marilyn Minter when we start talking about the Till controversy, “always eats its own.” We are at her studio in the West 30s. She’s invited over some members of the protest cell she’s a part of, Halt Action Group (which is behind @dear_ivanka), made up of members of the art world and those in its near orbit. While we’re waiting, one of her assistants finesses the design on her computer for a banner with the word RESIST emblazoned across it, for the upcoming Creative Time “Pledges of Allegiance” project, which asked artists to make banners expressing what they feel America stands for, or should. Another assistant sits at a table next to us painting one of Minter’s almost shockingly sincere commemorative plaques with Trump’s face embossed above the full text of his “grab them by the pussy” swordsman’s soliloquy in elegant gold type, like a historical marker for a Civil War battle on the side of a road.

Famous for her glittery, glamorously grotesque paintings and photographs of lips and eyes and shoes, Minter, at 68, has become one of the more beloved figures in the art world — a little bit Courtney Love and a little bit Auntie Mame. Her politics are passionate, generous, and of course very much of her generation. (For a while, in the 1990s, she was on the outs among certain feminist critics for being a bit too pornographic in her work, which at the time meant she was considered sexist.)

“I was born in Louisiana and grew up in Florida,” she explains. “I was radicalized because of civil rights.” She’s old enough to recall when her doctor wouldn’t give her birth-control pills because she wasn’t married — so she went to Planned Parenthood. Then, a couple of years back, she heard about the draconian new Texas and Ohio laws restricting access to abortion. The right to an abortion — she’d once had one herself — is something she remembered people not having. The idea that people might not, again, seemed inconceivable to her. And so she started fund-raising for the organization, getting other big artists (including “the boys” like Richard Prince) to donate pieces for auction. Among many things she finds unacceptable is Trump’s crusade against Planned Parenthood.

Her latest retrospective, “Pretty/Dirty,” opened the week before Election Day at the Brooklyn Museum. The show was to kick off that institution’s cavalcade of progressive programing called “A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism,” with the stated goal of “expanding feminism from the struggle for gender parity to embrace broader social-justice issues of tolerance, inclusion, and diversity.” It was timed to coincide with the tenth anniversary of the museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, but it was supposed to be well timed in other ways, too: We were about to elect the first woman president!

After Trump won, the meaning of the “Year of Yes” became the “Fear of No.” Minter was contacted by a few friends whom she’d worked with on Planned Parenthood fund-raising, and soon an ad hoc group had formed. They decided to target Ivanka Trump, who had over the years studiously exfoliated her father’s vulgarity to establish herself as a hardworking, clean-living Manhattan heiress, earnest and anodyne enough to be friendly with Chelsea Clinton and concerned enough with her social position as a person of taste and enlightenment to collect art. They did a protest next to the Puck Building, which Ivanka’s husband, Jared Kushner, had redeveloped as luxury housing, and launched @dear_ivanka. A Halt volunteer who is a psychotherapist helped fine-tune the group’s posts to push Ivanka’s buttons. The first one, with a picture of her in a red dress, read: “Dear Ivanka, I’m afraid of the swastikas spray painted on my park.”

Was all this maybe a bit too blunt, even juvenile? Possibly. But Ivanka, like her father, seems to want to be liked. “I know Dear Ivanka is working,” says Minter. “She’s not following me on Instagram anymore and she used to.”

The project got press (and 25,000 followers), and Minter and her friends began gathering other art-world pooh-bahs who wanted to be involved. They’re thinking of what they’ll do next. Horowitz has since left and started another anti-Trump Instagram feed, @dailytrumpet. The rest of Halt wants to sell the plaques in the Brooklyn Museum’s gift shop to raise money for more activities. There are plans to go national, with Halt L.A. and Halt Austin. “I don’t think I’m trying to reach the Trump supporters,” Minter tells me. “I think we’re trying to reach the 90 million people who didn’t vote. If we become the tea party from the left, we’re going to kill them.”

Gina Nanni, the prominent arts publicist, and artist Xaviera Simmons arrive at the studio. Both are Halt members.

“I remember making politically engaged art two, three years ago, and you were a little on the outs” among collectors, curators, and the chattering critic class, says Simmons. “And now you can’t get money in the door fast enough from the creative class.”

“Don’t you think that this election has changed everything for all of us?” Nanni asks. “I don’t look at fashion shows anymore. Who cares?”

“Art about art just isn’t working anymore for me,” says Minter.

“It’s not okay to just write a check. It’s all-out war,” says Nanni, who had been part of a different politically motivated arts collective, Downtown 4 Democracy, which in 2003 raised money to defeat George W. Bush. Many of the members were Howard Dean supporters (Nanni liked Bernie Sanders this time around). “Our goal was to get our cultural heroes involved, to get people off their butts. Lou Reed, Susan Sontag …” In other words, make politics cool again for the rigorously over it. “We did a lot of artists projects,” she says. “We got Marc Jacobs to do political T-shirts. I remember a New York Times reporter called me — someone not very friendly — predicting Marc Jacobs’s demise for doing this. But the opposite happened. People were lined up down the block. People just didn’t know what to do then: Nobody knew how to participate. You were just arguing over the dinner table.”

“What do you guys think of the people who say that this was the best thing that’s happened to left?” asks Simmons. “It woke us up.”

“Madonna said that,” Minter points out, at an event she did at the Brooklyn Museum, the day before the inauguration (Minter had invited her). “Well, the resistance is working. That must give you some hope.”

It’s not that the art world had been asleep, exactly. Groups like Occupy Museums tried to call people’s attention to a supposedly liberal system’s hypocritical inequities: its class and race problems, its being in the general service of its plutocratic and corporate patrons, however well meaning those patrons may be. But the Obama years were very good ones for contemporary art, and not always, if you thought about it too hard, for the best reasons. Maybe even for some of the reasons that Trump and the other populists and neo-nationalists point to as justifying their rise. As the global rich got more globally rich, they bellied up to contemporary art’s movable feast. Prices went up, as did attendance at an expanding and well-publicized global itinerary of art fairs, biennials, and museums, many of them privately owned, often in alliance with luxury brands. Kanye West and Lady Gaga and, yes, Madonna wanted to be involved. The aesthetic or intellectual novelty and subversiveness of the art itself often became muted by its plush setting, its intentions hard to discern while downing Ruinart Champagne from the cart that plied the aisles of Art Basel in Miami Beach.

None of this is new: Most artists, like most of us, want and enjoy success and like to live well. But did the boom ruin art’s ability to have moral authority? Can you resist while also being on the VIP list? As one dealer of multimillion-dollar art put it to me, “The art world just doesn’t feel as relevant. They don’t go to the places that voted for him. Lena Dunham doesn’t know these people. Posting on Instagram isn’t resistance; it just means that you pose as resistance.”

That’s the danger — that the art feels like posturing more than protest. “We know how trendy the art world is,” Hank Willis Thomas says. “And this is just on trend. After 15 years of doing art in one way, it’s great to be on trend. What happens when the trend is over is the question.”

There is a larger conceptual problem for artists protesting Trump, which is how to actually go about effectively doing it. What can the artists themselves do to go up against the policies of a president who is, in many ways, a kind of performance artist himself? How do the discontented, visionary weirdos muck with our reality when creating alternative realities is now the purview of our say-anything postmodern mad king? What do clever artists do when the world itself has become so darkly clever?

It doesn’t help that the fringe and the center seem to have switched places, that the person in the White House and his most noxious supporters have cast themselves as the true outsiders. Last October, Lucian Wintrich, a preppy provocateur who now has press credentials at the White House, put on what was billed as a pro-Trump art show in Chelsea called “#DaddyWillSaveUs: Make Art Great Again!,” featuring work by Milo Yiannopoulos and Martin Shkreli. It was boorish and desperate, but he had a point when he later told The New Yorker, in all seriousness, “Good art should be transgressive. These days, it seems, the best way to be transgressive is simply to be a white, male, proudly pro-American conservative.”

The Whitney Biennial at first seemed like a precisely calibrated response to those white male conservatives (not that most of them would ever see it). The show had been conceived under the subtle assumption that Clinton would likely win, and yet its themes — racism, inequity, censorship — were even better suited to our current political moment. But then, on March 17, the first day the show opened to the public, an African-American artist named Parker Bright stood in front of Schutz’s painting with a handmade T-shirt reading BLACK DEATH SPECTACLE on the back. It was a statement perfectly suited to Instagram, and it was widely distributed. Soon after, another artist, Hannah Black, wrote an “open letter” on Facebook calling for Schutz’s painting to be taken down and destroyed, explaining: “It is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun.”

The internet — most of which had not had a chance to take in the biennial and, for that matter, never will — reacted as the internet does: marshaling preexisting worldviews and arguments with imperious take-a-side disdain. The New Republic published a much-circulated anti-Schutz perspective; Hyperallergic was more skeptical (“Hannah Black and company are placing themselves on the wrong side of history”); Whoopi Goldberg chimed in (against censorship) on The View. Kara Walker, on Instagram, took the long view (“The history of painting is full of graphic violence and narratives that don’t necessarily belong to the artist’s own life”). And the artist Chris Ofili checked in with The New Yorker (“Seeing a painting and talking about a painting are two different things. One should not confuse sharp eyes with a sharp tongue”), which ran along Calvin Tomkins profile of Schutz, who sounded a bit tentative and abashed about the whole episode: “I knew the risks going into this. What I didn’t realize was how bad it would look when seen out of context.”

The museum stood by the painting, although it acknowledged the controversy on the wall text. Mostly its curators pleaded with people to see it in the full sweep of depictions and concepts in the show, which is hardly one-note. On April 9, the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, hosted a program to address the criticism and provide perspective. “Against the background of the current political climate,” Weinberg said in opening, “the exhibition touched a nerve.”

To say the least. The politics of the art world don’t always make sense to people not scrapping for intellectual cred as it is defined by the art world, and the situation is made more complicated by the ease of ricocheting commentary and the quick-to-arise mob moralisms of social media. But the worst outcome of the Schutz controversy would be if artists became afraid of that. As Thomas tells me, “I learned that you have to be willing to get your hands dirty if you really want to make an impact. You have to run the risk of being misinterpreted.”

In the circulating images of protest that have thronged social media since January, I’ve been particularly struck by the placards declaring GOD HATES IVANKA and FAGS HATE TRUMP, which took their graphical inspiration from those of the loathsome Westboro Baptist Church (known for protesting the funerals of soldiers and owning the URL “godhatesfags.com”). It turns out they were made by the artist Paul Chan and his small art-book publishing company, Badlands Unlimited.

I visit him and his crew at their offices in a walk-up on Rutgers Street, where Micaela Durand shows me a photo shoot they did of young people brandishing the signs. She explains the idea: “This is A Clockwork Orange, but with minorities taking the lead,” she says. “The whole purpose of the shoot is to inspire a type of new courage on the street. They’re kind of a look book to try to start a national campaign. To move the signs to the red states.”

It’s a refrain I heard a lot. Everyone in the art-“resistance” set is interested in doing something that could have an effect on the rest of the country, even those who joined up with the art circus precisely because they were running away from the dreary red state they were from. Chan was born in Hong Kong but grew up in Nebraska. He’s not new to politics, but usually his points are more oblique. In 2007, he worked with Creative Time to put on Waiting for Godot in the streets of New Orleans: “Two years after Katrina, everyone there was waiting for something,” he says. His exhibition at Greene Naftali, which closed April 15, included some of his “breezies” — ghostly comic-ominous sculptures animated by fans; some of them looked a bit like Klansmen.

After the election, his mind turned to Westboro’s signage, which can seem so bizarrely and pointlessly vituperative as to read as parody in the same way Trump and his fans on Breitbart News can. It gave him an idea: Troll the trolls. “We thought: We were angry. It should be hate against hate. The Westboro are hateful motherfuckers. They are really savvy and hateful. And their visual design is so iconic.” He made the first signs for the Women’s March. Reactions were not uniformly positive. “They were a big hit,” Chan says. “People loved them and hated them in equal measure, basically. The liberals were the ones who really hated us.”

“They were like: ‘God doesn’t hate anyone,’ ” says Durand in a slight singsong.

“We had Evangelicals trolling us and leftists trolling us,” Chan says. “Which I think is a good sign. We’re doing something right.” He paused and reframed. “We’re not looking to make peace. We’re looking to make everyone else feel just as unsafe as we feel.”

Badlands has in its office a map of the country with pushpins in it: The idea is that the group will sell the posters in places like New York and Los Angeles, at artist-run bookstores, then use the profits to fund donations of the posters in the hinterlands. It keeps making more of them; the favorite at the moment is TRUMP LOVES RAPE. The artists are premiering the signs at different rallies.

“We hear a lot about how we shouldn’t only preach to the converted,” Chan says. But he also sees that the complacency of New York is only beginning to be shed. “Just because you are against homophobes doesn’t mean you will step up when someone is being bothered on the subway. What the converted need is more courage, and the people who voted for Trump need a little more fear.”

They send me on my way with a TRUMP LOVES RAPE poster, colored pink, yellow, and orange.

*This article appears in the April 17, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.