At the time of the debut of her most recent public-art project, which was also her first public-art project, Kara Walker would clandestinely ride her bike from her home in Fort Greene to the then-defunct Williamsburg Domino Sugar factory, in which her massive sculpture was housed. The sugar Sphinx was raised in the summer of 2014; crowds as big as 10,000 people gathered to visually consume, and to Instagram, the monumental sculpture. Back then, Walker had dyed the top of her cropped Afro blonde, and her vague purpose in visiting Domino, she tells me, involved evaluating the people who had come to evaluate her work: She wanted to see how the moment of encounter with the colossus could change their faces. But Walker’s presence disturbed things, she says — as soon as viewers noticed, their eyes turned from the idol onto her, then they flocked in her direction. She was slightly exhausted by that, she says, still seeming a bit surprised. “I don’t know, I thought maybe people would be focused on the white-but-black gigantic labia!”

Commissioned by the downtown public-art fund Creative Time, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby induced, like any Kara Walker work, an equivocal ceremony of looking — who looks, at what, and how. The central sculpture — a Sphinx creature with the kerchiefed head of a mammy figure, her breasts naked, her vulva prominent — stood 35 feet by 75 feet, a chimera of unvarnished American desires, protected by an infantry of black-boy figurines carrying agricultural bounty, built from Walker’s sketches by a team of nearly 20 fabricators, the 3-D sculpting and milling firm Digital Atelier, and Sculpture House Casting. A foam skeleton overlaid with 40 tons of sugar, water, and resin, the Sugar Baby was the largest single piece of public art ever erected in New York City. It was also one of the biggest in another sense: The show attracted 130,000 visitors, briefly lived a convoluted life as a coveted social-media geo-tag, and seemed, given the many pilgrims it enticed, to herald a new future for public art in the city. As Nato Thompson of Creative Time told me, “Kara immediately understood what a different form public art can be.”

The Sphinx was not meant to be a crowd-pleaser; it was too challenging for that, with compressed politics that were the result of what Walker calls her “magical thinking.” The Sugar Baby’s extended title referred to the workers who had been degraded, maimed, underpaid, and killed in factories like this one: “an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant.” The sculpture was a feat of reengineering, its materials not only sugar but also the events running through it: the brutal repurposing of black human life for the rank, commercial lusts of white supremacy; the emphasis on black female biological potential over black female creativity; both the bygone and contemporary processes of gentrification that threaten to wipe all indications of these dark and abiding practices from the structures in which they occurred. The developer Two Trees, which underwrote much of A Subtlety, broke ground on its Domino project not long after, turning the site into new apartments, and the Sugar Baby was conceived to be wiped away, too — to be almost completely destroyed following its single showing. But while it was up, Walker wanted to be sure to scrutinize how it was received, and sent a camera crew to film the crowds as they preened, laughed, and selfied around her — producing a kind of surveillance footage. Then she screened the result at Sikkema Jenkins, the gallery that has represented her since 1995.

It’s been nearly three years since the Sphinx, and Walker has spent the time interrogating what it means to make monumental and political art — representational or abstract — on the terrain, sites, and buildings in which the lives of black people have been compromised in some way. That is, how to exhume the traumas and delights of an environment rather than fabricating scenes out of black paper — and how to guide the problem of how people look. “I am still wrestling with my relationship to what my art might do in the public space,” she says. “How I can control it.”

Entering any room, Kara Walker redirects the flow of attention. She is tall, and her posture is strictly vertical, rarely lax, as if her neck were cinched to the goings-on of a higher plane. Standing in the foyer of her Fort Greene brownstone, the artist wears nondescript black workwear, Timberland boots, and her hair in utilitarian plaits.

Walker first became famous, quite abruptly, at 25, with her landmark 1994 show “Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” — a stunning mural installation of cut-paper silhouettes depicting antebellum horrors that remains, by far, the most notable exhibition the Drawing Center has ever mounted (and which at the time thrilled and repulsed viewers, including a constituency of older black artists suspicious of her ease with racial stereotypes). Walker seemed to arrive fully formed, an American confessor exposing the terrors of sentimentalist history. Like the Spanish master Goya, to whom she is often compared, Walker carefully excavates the horrors of her country, rendering the events in stark black-and-white contrast on cut-paper tableaux, paintings, drawings, and sometimes films. A picture of a little girl in profile she found in an academic text aroused a point of entry for her early on in her education. In graduate school at RISD, she pursued the classically vulgar silhouettist style, which allowed her to conflate the ideologies of cartooning with a wry necropolitics. Out of the appalling details of slavery-era subjugation — the contour of a disembodied male arm emerging from a girl-child’s skirt, a master’s penis approaching the slack maw of a slave-woman — Walker makes commanding work that hews not to the black bourgeois ethic of psychic uplift nor to the art-world tradition of producing to market.

Now 47, and a new kind of public figure thanks to the Sugar Baby, Walker remains suspicious of herself, and of the world, however much it has come to celebrate her, expressing to me the bewilderment of a thinker for whom no level of success can stamp out a phobia of personal self-satisfaction — or, worse, infidelity to craft. We talk at her home, by phone, and in her studio, where she brings me one cold day in March. She can be especially mordant in talking about the predicament of the famous black fine artist, a position she’s occupied for 23 years. “We’re in too much of a celebrity culture,” she says, “but at least that means I can be a disappointment to others.”

Walker’s 2007 traveling retrospective “My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love,” which drew enormous crowds to the Whitney in New York, cemented her status as a present-day master — and one with an especially urgent set of concerns. The art Walker has produced in the decade since the retrospective is loaded with references to contemporary emergencies that compound, rather than replace, the lynchings, rapes, chases, and captures of Walker’s translation of the pre- and post-Reconstruction South. The last few years have brought events that fleece the sweet false parable of post-racialism of its saccharine optimism: “I fear that Michael Brown and Tamir Rice and all the rest were killed as proxies for The Black President,” she wrote in an essay called “Assassination by Proxy,” published last September.

Walker did not watch the inauguration of President Trump, she tells me, having brought me to the Garment District studio she has occupied for seven years. Instead, she painted The Crossing, a 9-by-12-foot watercolor that references Leutze’s 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. The painting, which I see bubble-wrapped behind her movable wall, appeared in The New Yorker in February. Currently, she’s working on another wretched scene of interracial confrontation. “It will be finished in a few months,” she says, pointing to the most striking action: a naked black woman whipping a police officer dressed in riot gear. The reference for this painting sits on a bench beside drawing paper and Conté crayons — The Slave Trade, by François-Auguste Biard, in the fourth volume of The Image of the Black in Western Art.

But her next two projects will be public works, a sign that the Sugar Baby might have been the beginning of a new period, however cautiously Walker has found herself wading into it. “After A Subtlety, everybody was asking me to do something in a grist mill or some industrial setting,” she says. Last year, megacollector Dakis Joannou’s deste Foundation for Contemporary Art offered a former slaughterhouse on the island of Hydra in Greece; beginning on June 20, the left hand of the Sugar Baby, making the figa gesture, will be displayed in the center of the facility. “What’s going to happen is, this summer, the important art people of the world are going to go to the Venice Biennale, and then they’re going to go to Art Basel, and then some of them are going to get on a boat and come to Hydra and see something they’ve already partially seen,” she says confidently. Currently, it’s sitting in a box in a storage facility “in New Jersey or Long Island.”

“I just felt conflicted,” Walker says, speaking of the hand. “I destroyed the whole piece but I felt something should remain. I didn’t keep the head around because I didn’t want her just sitting around, staring at me.” The interaction of art and place will no doubt inspire prognostications about the nature of relics in the age of the migrant crisis, about the line connecting the genesis of democracy in Greece and the mutilation of women in America. But right now all the curators are worrying about is how they’ll get the gigantic hand through the slaughterhouse door. Walker isn’t. “ ‘You may not cut the hand in half,’ ” she says she told them. “I can make another piece, but I don’t want to, since we’re running out of time,” she says.

And then, this fall, in New Orleans, an ambitious new work. Walker, together with an engineer and a composer, will fabricate a novel musical instrument and have it play macabre versions of traditional protest songs from its whistles for the Prospect. 4 festival. She conceived the idea when visiting Algiers Point, a site where slaves were held before being auctioned in the 18th century and black men were shot on sight by white vigilantes in the 21st, just days after Katrina viciously rearranged the earth. She is hoping to set the project there.

In the meantime, a looming move: In May, Walker will transfer her work from Manhattan to a spacious studio in Industry City with a parking lot for snow trucks, a view of the Ikea loading dock and, a bit further off and obscured by fog when I visit, the Statue of Liberty. The move is practical — the new development is much closer to her Brooklyn home, and the rent in midtown has grown exorbitant. The new studio is one massive, rectilinear room with white walls. A recessed cove will serve as an office, and the rest of the space will be divided into a kitchen, two areas for her two assistants, and an open workspace for Walker to produce her paper arts.

She’s still affectionate for the old space.

“The Garment District is certainly inhospitable to making art, which is why I love it here,” Walker says back in midtown. Every artist partially lives in her workroom, where the relics of failures and half-thoughts are accrued in strange arrangements. The cliché is that the organization of a studio is chaos to everyone except for the artist and her assistants. Walker and one of her assistants had repeatedly described the old studio, in the midst of the move, as messy, but her space looks orderly to me. The cavernous midtown room is stacked with boxes labeled books, office, bookshelves. Elsewhere are photo albums, historical textbooks for reference, her mother’s quilt. There is a creaky ladder she’s owned for more than a decade. On a gray sectional is a gigantic teddy bear Walker bought from a nearby pharmacy once, after a rough day. Beside it, Italian hand puppets. She squats down, putting on a spontaneous show.

She lingers over a box labeled for OCTAVIA & KLAUS. Walker moved to New York in 2002, after having accepted a teaching position at Columbia University. Before that, she’d been living with her then-husband, the jewelry designer Klaus Bürgel, and their young daughter, Octavia, in Providence. Walker delayed the initial move to New York for months, a time she remembers mostly as folding laundry in a house in Maine, where Bürgel had a brief teaching position. She gave up the Maine house and a black Isuzu, which she sometimes misses driving around the city; the divorce was only finalized in 2010. “I certainly had no problem with getting successful at the age that I did,” Walker says. “But I wasn’t the only one in the marriage.”

“She isn’t a diva,” says the novelist James Hannaham, Walker’s cousin, collaborator, and close friend. “But Kara just always knew she would attain a certain level of fame.” “Gone” made Walker a sensation at 25, the year she completed her MFA at RISD; the following year, she produced The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven. She earned a MacArthur “genius” grant two years later, one of the youngest ever to do so. That she was ever loathed, especially in the wake of the Sphinx, may seem odd.

Depending on whom you ask, the campaign against Walker was motivated by an intraracial or a matricidal anxiety. In the ’90s, a young black avant-garde — Walker, Glenn Ligon, Michael Ray Charles, Lorna Simpson — felt liberated (by postmodernism, among other things) from the shallower agendas of affirmative art. This liberation appeared to some older artists as a betrayal of tribe.

“I felt the work of Kara Walker was sort of revolting and negative and a form of betrayal to the slaves,” said Betye Saar in 1999; two years earlier, she’d staged a letter-writing campaign asking that Walker’s work be censored and destroyed. “She’s in deep trouble,” said the photographer Carrie Mae Weems at a symposium held at Harvard in 1998 about the use of black stereotypes in image culture. “But then so are all of us — in deep trouble.” An entire issue of The International Review of African American Art was devoted to dissecting the morality of her work. Walker’s bluntness underscored the issue. “I think really the whole problem with racism and its continuing legacy in this country is that we simply love it,” she wrote in a 1997 artist statement. “Who would we be without the ‘struggle’?” Failing to identify with “the struggle” meant a failure of aesthetic and professional solidarity.

Today, Walker keeps that issue of International Review on her bookshelf, along with another work called Kara Walker—No/Kara Walker—Yes/Kara Walker—?, published in 2009. “What are they debating, really? My right to exist?” she asks. “I was getting a lot of letters and phone calls. People were concerned about me. They were excited to see the work but also concerned about the endemic racism of the gallery system, that I might be swallowed up and spat out by a gallery because of the sensationalistic quality of the work,” Walker says of the mid-1990s. “I created this space where I as the artist was also the Negress who is to some extent living in the master’s house or vying for the master’s attention.”

Walker has played with this provocation — of figuration versus personhood, and the relationship of her own identity to those bodies depicted in her work — ever since. She sometimes refers to herself as a “Negress of noteworthy talent,” a reference to the slave girl-child character Hilton Als once identified as the “saint figure” of her compositions. She looks to the languid narrators of southern novels like Gone With the Wind for the flamboyance and piquancy of her drawings. To Walker, art is description, not advertisement. To those who say she might be politically alienated, or that she doesn’t exhibit much black allegiance, Walker more or less agrees. “I recognize it when I see it in other people, and I recognize it in myself. Even my dealer [Brent Sikkema] would say, ‘People would reach out to you and you seemed to be someplace else.’ I’m older now, but I really lacked empathy in a way I did not realize. Desensitized. Not fully grasping … the ‘positivity’ of black life and looking more closely at cruel native spaces. But I do that because I’ve lived in that space quite a lot.”

“I’m sure she knows the difference between herself and the Sugar Baby,” says Hannaham. “She knows that her work and persona is a lightning rod for what she calls ‘the pathologies’ that are everywhere in the country. But she also knows that putting a naked representation of a black woman in a public space invites all sorts of projections, bullshit, and reverence. She likes that.”

“Many black artists do prefer to make affirming images,” says historian Nell Irvin Painter, author of (among other things) The History of White People. “But many others want to make whatever images their eyes take them to, whether affirming or not affirming.” The controversy remains a live one. In 2013, Painter and Walker participated in a public dialogue following a controversy at the Newark Public Library. Scott London had sent Walker’s graphite drawing the moral arc of history ideally bends toward justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos to the library on loan. Its loquacious, literary titling belies the overtness of its chaos: floating figures engaged in states of amoral hygiene. A figure of President Obama wags a condemning hand over a podium, a naked black man clutches a fleeing figure, and the head of a black woman is forced into a white man’s crotch. Employees at the library decided to cover the painting with a sheet.

“It’s funny, there’s a way in which the accusation of stereotype reveals more of how their eyes work versus how my work works,” Walker says. “I wouldn’t make art if it were purely an ego-driven exercise.” Then, calmly, she moves in another rhetorical direction. “If the work is reprehensible, that work is also me, coming from a reprehensible part of me. I’m not going to stop doing it because what else could I do?”

“Even as interest turns her way, Kara Walker is not excitable,” says Hannaham. “Kara is almost as calm as Obama. She has the hermeneutic idea of the role of the artist in society — a person who is strong enough to withstand projection and then can project ideas back to the people in such a way that their minds change. Or not.”

Walker speaks at a hushed but youthful clip, which makes it seem like the artist is sometimes startled by the drift of her own brain. She will dole out a terse declaration — “I’ve been disinterested over the years with my own family history” — only to soften a moment later — “This is my childhood couch,” she says, gesturing to the gray piece of furniture in her living room.

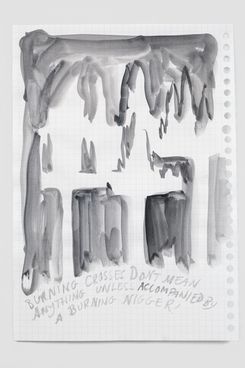

Born under the constructed glow of “golden multiculturalism,” as she calls it, in Stockton, California, in 1969, Walker moved with her family to Stone Mountain, a suburb of Atlanta, in the mid-’80s. Her father, the artist Larry Walker, had gotten a job at a university. The area is named for the geographical feature on which a conspicuous bas-relief was dynamited into existence post-Reconstruction, a propaganda carving of the Confederate martyr figures Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. There, Walker endured the double adolescence of black childhood: the common social ritual of becoming an adult and then the explicit social ritual of becoming a black adult. “Perhaps you could say that much of my work is an endeavor to disappoint my father,” she jokes. Later, she clarifies: Walker père appreciates his daughter’s oeuvre, but has asked, when considering a negative-space watercolor of burning crosses called Burning Crosses Don’t Mean Anything Unless Accompanied by a Burning Nigger, “When are you going to get over this race thing?”

Curiosity guides Walker, even in the difficult milieu where stereotype and humanity collude, where the mammies, tar babies, demonic masters and their apathetic wives live. As she tells me about Georgia back at her house, she places ginkgo and black teas at a pale wood kitchen table. Her cat, the plump and ornery Pearl, has taken up residence someplace unseen outside the kitchen’s screen door. Next to notebooks and stray pencils is a laptop that holds video Walker filmed, unsteady shots documenting the circuit of civil-rights landmarks and stone Confederate erections that surrounded her as a teenager. Two years ago, Walker realized the rock’s intrusion into her daily horizon made it an icon of technique and of subject, to say nothing of the allure of uncut ideological brass. “I make work that’s historical, that’s profiled, that’s cut out. There was a moment, looking up at it, where I knew that this” — she pauses before finding the word, which is right but not appropriate — “this monument was the biggest influence on my work,” Walker says.

Since A Subtlety, trips have provided Walker novel filters through which to see her familiar American ruins — and possibly some strategies to revivify them. Last year, she completed a residency at the American Academy in Rome. “Going to Rome was good medicine, a little distance on the violence in America, and a cultural break from being perceived as a black girl,” Walker wrote after the trip. And earlier this year, she led a group of graduate students she teaches at Rutgers down to Atlanta, America’s premier black bourgeois metropolis, and its mellow environs, including the small town of Franklin, her father’s birth town. Nominally, it was a resource trip to collect rubbings and video for an installation. But she also found herself conducting personal business, visiting Old Friendship, a dilapidated cemetery that held several of her ancestors’ remains. For more than two uninterrupted centuries, segregationist codes decided where and with what flourish her people could lay their dead, she says, recounting the trip. “I wonder if I half-expected something to jump out at me. Like the idea of a ghost.”

Were it that sort of morning, the works on the walls of Walker’s open-plan living space would have been streaked with light. There is a portrait of a black man in profile by the Ghanaian-British painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye that Walker acquired in a trade with the artist. Photos by Ari Marcopoulos take up most of the wall space: Jean-Michel Basquiat nude in his tub, a zoomed-in shot of the black soldier at Grand Army Plaza’s Soldiers and Sailors Arch, and a gold-framed portrait of the rapper Pusha T, looking imperious in an expensive white T-shirt. Marcopoulos himself is in the living room, grazing through Walker’s vast record collection. He chooses Miles Davis. “I’m sure people already figured it out, but if they didn’t know yet, they’ll know now,” says Walker, raising up her arms.

Marcopoulos and Walker met when he took a portrait of her in her old Garment District studio; they live together now. For the past few years, they’ve collaborated on books, pamphlets, and exhibitions. The photographer went with Walker to Atlanta in 2015, helping her to collect the impressions that would compose “Go to Hell or Atlanta, Whichever Comes First,” her 2015 show at Victoria Miro in London and her first major exhibition after A Subtlety. Marcopoulos had an insurgent fantasy of slowly vandalizing Stone Mountain by planting wisteria on its seditious face.

When Walker entered the Atlanta College of Art in 1987, she had yet to develop her silhouetted antebellum world. An etiquette of racial politesse guided her studies. And Walker says she tended toward a cartoonist style, regardless of the subject. She loved Andy Warhol and Charles Schulz. (Schulz sent Walker a cartoon and letter, which she stores in the library on the top floor of her home.) “It had to be historical, as well as figurative, and it had to speak to the whole range of black consciousness,” she says, enumerating the Atlanta-art-world expectations. She read her Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler on the side, she says, but “I was sort of tsk-tsked by the other classmates for not doing blackness in my work. I just always thought it was too direct. I thought I was going to do it wrong. My lack of edification, or my lack of clarity on what black identity could be in my own experience … I just thought I was going to put my foot in my mouth if I was honest about my own failings as a black woman.”

“Don’t look,” Walker says, after leading me to the computer in her midtown studio. The sound of a freakish wind instrument fills the room, playing a dirge whose melody is at odds with its high pitch. “I was walking down an uncomfortably picturesque street in the Ninth Ward, and I heard this alien sound,” she says of a recent trip to New Orleans. She pulls up a video of the Steamboat Natchez, which operates on the Mississippi River. Walker first responded to Hurricane Katrina and the racialized, wrecking power of water in the “After the Deluge” 2006 exhibition at the Met. But she isn’t yet finished reckoning with that flood.

“New Orleans is its own art piece,” Walker says. For her, the dilemma of a site-specific project is one of reconciliation. The site provides the medium, and often the subject, too. But conceiving a project entirely through a space is a surrender. Walker is adjusting to the ritual, developing a method of producing works of monumental art over which she maintains authority.

When Walker first visited the Domino refinery in 2013, the whole place overwhelmingly “stank of molasses,” she recalls. “The history would not dry.” The sugar-baron Havemeyer family opened the complex on the Brooklyn waterfront in 1856; much of the initial sugarcane harvesting was done by slaves. An 18th-century missionary poet, shaken by the violent exigencies of cultivating and cutting sugarcane, theorized that inevitably, blood was in the sugar — symbolically, sugar might have then been in the blood. By 1870, the Williamsburg refinery, which got renamed Domino Sugar in 1900, was producing more than half the country’s supply of sugar.

Algiers Point presents a different challenge: The blood of the black dead was spilled so recently; its memory still courses. By making a cyclical performance piece, she realized, Walker had the opportunity to honor the past, and the city, without giving up control. “The instrument will be a performing object, one that will have an effect on the nerves, maybe,” Walker says. She is still figuring out the vessel to carry the instrument, a wagon that “may or may not” take human form.

Walker tells me that New Orleans may become something like the next iteration of a project she half-abandoned two decades ago in Minneapolis. When she installed that silhouette mural, called Slavery! Slavery!, she’d hoped to extend the round room in which the cut-paper scene was mounted, like the Civil War cyclorama at the Atlanta History Center. “I imagined that all the cut-paper pieces were existing on the same landscape somehow, and that if you put them all together you’d be in this endless cycle.” That way, she explains, the work would be both monumental and animate — all the binaries of the “master-slave” dialectic would constantly reassert themselves, and though there would be moments of exit, escape, and resistance, the theater of carnivalesque action would not end. She calls the result a kind of “plantation fantasy,” one that she is trying to figure out how to remote-control from Brooklyn. Then she pauses. “I’m saying something out loud that I hadn’t even admitted to myself,” Walker says. “So there you go.”

*This article appears in the April 17, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.