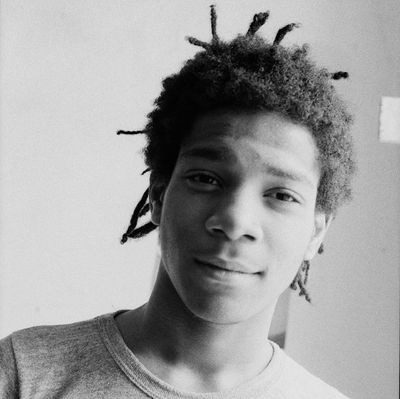

As its title implies, Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat takes a circumscribed time frame: Basquiat’s emergence as a charismatic kid going to shows in the close-knit post-punk Lower East Side of the late 1970s, selling his first painting in the early 1980s, and launching himself into the stratosphere.

Director Sara Driver was there at the time, and draws on her Rolodex of friends, scene survivors, and friends of Basquiat — including her longtime romantic partner Jim Jarmusch, who, in his brief interview, retells a story they both presumably remember, of the time Basquiat interrupted them on a “nice little romantic walk” to give Driver a flower.

Basquiat is presented as a world-historical genius who both passed through that time and place, and was a product of it — an ambitious, curious creator and careerist who was inspired by the cross-currents of New Wave and hip-hop, street and Pop art, DIY filmmaking and squatting in New York during the years following “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” Driver re-creates the era with copious archival material: not just news clips and private snapshots, but art, and especially films made by her and Basquiat’s friends and fellow travelers during the era. Below, we’ve created a glossary elaborating on many of the sources and references within Driver’s dual portrait of a quintessentially New York man and milieu.

Sara Driver

Boom for Real is Driver’s first feature directorial credit in a quarter-century; her last, When Pigs Fly (1993), was a latter-day screwball comedy about ghosts and gentrification. During Boom for Real’s discussion of heroin, Driver inserts a haunting image of corpses lined up from her short film You Are Not I (1983), a surrealistic Paul Bowles adaptation that was considered lost for many years. Driver’s is one of the great semi-legendary filmographies; this month, Anthology Film Archives presents a program of films to supplement the release of Boom for Real, including her masterpiece Sleepwalk (1986), in which a single mother played by Nan Goldin associate and subject Suzanne Fletcher has a series of spooky encounters in a deserted, eerily quiet nocturnal Soho that seems to be governed by Symbolist dream logic.

Jim Jarmusch

Jim Jarmusch, like the canny self-promoter Basquiat, seems to have one already eye on posterity as he poses insouciantly in snapshots with his NYU film school classmate Driver — they make a striking young couple. Boom for Real features clips from his inventive, French New Wave–indebted first feature Permanent Vacation, and the soundtrack features the Del-Byzantines, the band Jarmusch was in alongside Sleepwalk composer Phil Kline, cultural historian Luc Sante, and filmmaker James Nares. Jarmusch’s own assessment of Basquiat’s philosophy of art and influence might double as a mission statement for his own hipster filmography: “Tak[e] things from everywhere and if they move you they become part of you and you can put them back out.” He and Basquiat share a simultaneous swagger and self-awareness in the way they inserted themselves into art history.

The Blank Generation

Driver sets the scene with clips from this year-zero punk document from the microgeneration that immediately preceded and overlapped with hers— and affirmed downtown New York as a place, as one of Driver’s interviewees says, to reinvent yourself. Co-directed by key “para-punk” filmmaker Amos Poe and Patti Smith Group member Ivan Král, The Blank Generation is a montage of songs, performances, and home movies from CBGB’s acts like Blondie and the Ramones. As its title — borrowed from the Richard Hell song, of course — implies, it’s a work of outcast mythmaking.

James Nares

A painter and musician, Nares exemplifies the interdisciplinary crossovers within the close-knit downtown scene, and the diverse artistic energies that Basquiat would draw on for his intellectually voracious work. Driver inserts clips from several of Nares’s short films as stock footage of desolate NYC — though perhaps the film of his most relevant to the milieu is the feature-length Super 8 film Rome ’78, a sort of scenester toga party featuring a Who’s Who of downtown artist types play-acting at legendary decadence in somebody’s apartment. The film’s hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show and quotation-marks irony reflect a fertile era brimming with creativity and prankish self-confidence, and its proud amateurism and bold personality parallel the unpredictable lines and inimitable flair of Basquiat’s paintings.

Vivienne Dick

Boom for Real offers us a mystical glimpse of Like Dawn to Dusk, an Ireland-shot avant-garde short from the feminist No Wave filmmaker. You can see Dick’s best-known film, She Had Her Gun All Ready — a feminist psychodrama starring No Wave musicians Lydia Lunch and Pat Place, and climaxing on the Coney Island Cyclone — at Anthology, and, later in the month, at BAM.

Jacob Burckhardt

In the East Village of Basquiat’s era, white flight had left old tenement buildings abandoned or burned. It was a place where squatters and artists could live cheaply — as Basquiat did in an apartment on East 12th Street with interviewee Alexis Adler, who put together a show last year of the very early, very experimental work he did with street junk and the walls of the apartment itself. Much of Boom for Real’s footage of the bombed-out Lower East Side comes from the hard-to-see films of Jacob Burckhardt, including Marten’s Bar and the gentrification story Landlord Blues, which draws a line from his father’s Rudy Burckhardt’s Beat films to the era immediately preceding the Tompkins Square Park riots.

Jorge Brandon

The starving artists of the Lower East Side lived alongside the neighborhood’s Puerto Rican community, and their art spaces emerged in parallel. In Boom for Real, we get a glimpse of Jorge Brandon, the spoken-word artist who recited on the streets of “Loisaida,” and whose legacy persists in the neighborhood that’s still home to the Nuyorican Poets Café. Basquiat, whose Puerto Rican mother helped foster his early interest in art, would incorporate rogue poetic text into his own art practice, both his early street art and later paintings.

Dream City

As one of the two guys behind downtown’s ubiquitous SAMO© graffiti tag, and its accompanying cryptic slogans (Al Diaz was his partner), Basquiat became notorious for his spin on street art, at a time when writers were using subway cars and city walls as their canvas. Driver uses some footage of whole-car murals taken from photographer Steven Siegel’s 1986 “city symphony” film Dream City.

“That’s the Joint”

On the soundtrack of Boom for Real is this early hip-hop classic from the Bronx’s Funky 4 + 1 — Robert Christgau’s favorite song of the 1980s. The Funky 4 + 1 were the first hip-hop group to perform on national television, on the Valentine’s Day, 1981 episode of Saturday Night Live hosted by “Rapture” emcee Deborah Harry.

Mudd Club

Tribeca’s cool-kid clubhouse, name-dropped by the Talking Heads in “Life During Wartime,” was co-founded by art curator Diego Cortez, interviewed in Boom for Real. The Mudd Club is represented in Boom for Real as ground zero for the mixing of uptown and downtown cultural scenes that Basquiat would also synthesize in his art. Particular attention is paid to the street-art show Beyond Words, co-curated by graffiti artist (and future Yo! MTV Raps host) Fab Five Freddy, on behalf of Keith Haring, who like Basquiat referenced graffiti in his more gallery-friendly canvases. Beyond Words also featured the first Lower Manhattan performance by hip-hop and dance music pioneer Afrika Bambaataa before his residency at Negril, included in Boom for Real via footage shot by interviewee Michael Holman.

TV Party

Boom for Real is dedicated to the dapper journalist-about-town Glenn O’Brien, who died shortly after being interviewed by Driver. Among many, many other things, he was the co-host of the talk show TV Party, sort of a more anarchic Tonight Show for the downtown set, birthed in the early, wildly democratic days of NYC public-access cable. Basquiat was a regular guest, alongside Bowie and other scene elite. Extended clips of his episodes can be seen at the TV Party program screening at Anthology on May 5, including several newly restored episodes not seen publicly since their original broadcast.

Wild Style

Much of the graffiti footage in Boom for Real is harvested from Charlie Ahearn’s film of the early hip-hop movement, made in collaboration with Fab 5 Freddy, and starring the graffiti artist Lee Quiñones. Another melting pot of New York’s white and black cultural hierarchies, the film features hip-hoppers like Grandmaster Flash and members of the Funky 4 + 1 scratching, rapping, and breaking to beats taken from original music by Chris Stein and Vince Ferraro, from the TV Party house band. See it at Anthology on May 6, with Ahearn in person.

Downtown 81

Glenn O’Brien wrote the screenplay for this long-unseen film, which went unreleased until 2001. Downtown 81 provides Boom for Real with much of its footage of Basquiat, who stars as a struggling artist wandering the city; tagging walls with SAMO© pieces, taking in shows at the Mudd Club and elsewhere by No Wave bands like DNA, Tuxedomoon, and James White and the Blacks; and having a series of picaresque encounters. Deborah Harry’s opening voice-over proclaims that “Fairytales can come true, sometime it might happen to you, especially when you’re young in New York, but once upon a time this place was the wild frontier, and every youngster who was fast on the draw showed up on these streets to try his hand.” The film’s loose, sociable structure documents a time when, as Boom for Real’s interview subjects discuss, downtown felt like much more of a village, one offering the opportunity for chance street meetings, and familiarity with a community of potential collaborators.

Produced by frequent No Wave film star and eventual Madonna accessory designer Maripol, Downtown ’81 also features John Waters muse Cookie Mueller as a go-go dancer, and the experimental musician Walter Steding (seen in Boom for Real playing the violin on the Williamsburg Bridge in his trademark light-up goggles, in footage shot by David Schmidlapp, which you can also see at a Boom for Real show at the East Village’s Howl! Happening). The soundtrack also includes John Lurie’s Lounge Lizards, “Cavern” by Liquid Liquid, and the sample on Melle Mel’s “White Lines.” Driver’s use of Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream” at the end of Boom for Real may be a reference to Downtown 81’s closing needle-drop of the similar-sounding “Cheree.” It’s at Anthology on May 4.

Gray

Both Boom for Real and Downtown ’81 feature music by Basquiat’s band, which, like other Mudd Club bands, mixed intellectually challenging free jazz with the DIY spirit of punk. Gray reflected both the black social consciousness threaded throughout Basquiat’s work, and the belief that you didn’t have to be a great musician to be a rock star. Basquiat’s bandmates included Michael Holman, also a party promoter and filmmaker whose shorts are clipped in Boom for Real, and, briefly, Vincent Gallo.

Club 57

We’re told that the young Basquiat was notorious for creating “havoc” in the ladies’ bathroom at Club 57. The Polish church basement on St. Mark’s Place turned performance space hosted Boom for Real interviewees like street artist Kenny Scharf and activist Sur Rodney (Sur), Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency slideshow, curator Ann Magnuson’s Flintstones dance parties, and Klaus Nomi. (Maybe you saw the recent MoMA retrospective?) The acid-washed theatrical spirit of Club 57 had an immediate heir at the Pyramid Club and its definitive film document, Liquid Sky.

Greer Lankton

Fittingly for an artist whose work is regularly reproduced on clothes and other consumer goods, Basquiat dabbled in fashion design with his “Man Made” clothes and early show at the boutique of future Sex and the City costumer Patricia Field. He was in storefronts before he was in galleries. In this, as Boom for Real points out, Basquiat follows in the footsteps of the late Greer Lankton, the trans artist known for her disturbing dolls and her window displays at Einstein’s, the alt-couture store run by her husband Paul Monroe at 96 East 7th Street (where Trash and Vaudeville is now). Lankton was a friend of Nan Goldin’s and a regular photographic subject.

Ann Messner

Boom for Real devotes a great deal of time to Collaborative Projects — “CoLab,” the artist collective founded by many of its interview subjects, who put on wide-ranging, democratic shows at which Basquiat was first a gallerygoer, then a star attraction. The spirit of CoLab comes through in the film through stills and accounts of its Real Estate Show — a group show at the abandoned 123 Delancey Street — and through clips from CoLab-affiliated works like Messner’s Subway Stories, in which the artist wanders through a crowded subway car in a wetsuit and goggles, to the bemusement of her fellow commuters.

Sol LeWitt

In contrast to CoLab, Boom for Real offers up the more established Soho gallery scene of the 1970s, with its emphasis on minimalist and conceptual work in the wake of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. In one montage, Driver includes a photo of Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #260, On Black Walls, All Two-Part Combinations of White Arcs from Corners and Sides, and White Straight, Not-Straight, and Broken Lines, a spare, orderly work which stands in contrast to the vibrant wall murals of graffiti artists like Lee Quiñones and Fab 5 Freddy, as well as Basquiat, with the proudly drippy spray paint of his SAMO© piece. (In the film Manhattan, Woody Allen is aghast that Diane Keaton considers the in-vogue LeWitt to be overrated.)

Times Square Show

The biggest CoLab event, the Times Square Show was a massive group show which ran throughout June 1980 in a former massage parlor on 41st and 7th, and was a breakthrough moment for the downtown visual-arts scene. It featured works by Charlie Ahearn, Jenny Holzer, and Kiki Smith alongside graffiti artists. It also attracted rapturous writeups in the mainstream press, including a cover story in the Village Voice in which longtime staffer Richard Goldstein noted that “Samo, the graffitist, seems perfectly at home amid the post structural scribbling on these walls.”

Jack Smith

Driver includes a promo video for the Times Square Show, directed by the No Wave filmmakers Beth B and Scott B, and featuring the experimental filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith, resplendent in cape and Mephistophelian goatee. Smith’s legendary underground film Flaming Creatures, shot on a Lower East Side rooftop and frequently attacked for obscenity, would be an inspiration for subsequent generations of flamboyant, transgressive, anarchic, and unschooled artists.

William Burroughs

Jim Jarmusch was a sound recordist on the 1983 documentary Burroughs, clips of which are included in Boom for Real as the film makes connections between the Naked Lunch author’s cut-and-paste prose and Basquiat’s own early stabs at writing. Basquiat’s later practice of “sampling” images, texts, and ideas in his paintings would be a more modern, fully realized version of the “cut-up” technique; a heroin habit would later be another, acute parallel between the two bohemian legends.

Andy Warhol

More than just an early supporter of Basquiat’s work during the tail end of Boom for Real’s time frame, Warhol was a huge influence on his generation as a whole. As Fab 5 Freddy tells Driver, Warhol was an inspiration for his multidisciplinary practice: paintings, films, involvement in performances and music; his constant cool-hunting and collaborations; and his interest in attracting attention to art through commercial self-promotion. Warhol’s Factory, which manufactured “superstars” out of the misfits finding a home and discovering themselves in New York City, would be the template for a downtown art world that didn’t wait for permission from the Establishment to treat Basquiat as a superstar of their own.