The late Stan Lee was fond of saying that Spider-Man resonated with wide swaths of humanity because anyone, regardless of color, could be under the mask. But there’s a more direct way of talking about race in the context of the character that is more compelling. A couple of years ago, I interviewed novelist Walter Mosley about comic books. At one point, the lifelong geek was talking about the early adventures of the first Spider-Man, Peter Parker, and he said something that’s rattled around in my head ever since, which I’ll quote in full:

The first black superhero is Spider-Man. He lives in a one-parent house — it’s not even a parent, it’s an aunt. He has all of this power, but every time he uses it, it turns against him. People are afraid of him; the police are after him. The only way he can get a job is by taking pictures of himself that are used against him in public. [Newspaper chief] J. Jonah Jameson says to him, ‘Go out and take a picture that shows him with his hand in the cookie jar, that shows him stealing and being a villain.’ That’s a black hero right there. Of course, he’s actually a white guy. But black people reading Spider-Man are like, Yeah, I get that. I identify with this character here.

Peter Parker is, indeed, white, but Mosley was onto something: More so than most superheroes, for the reasons he listed, the Spidey archetype lends itself to commentary on what it means to be a person of color in America. How lucky we are, then, to have the opportunity provided by Miles Morales. Introduced in comics in 2011, the character is an Afro-Latino teenager who was, much like Peter, bitten by a fateful spider and granted spectacular abilities. Initially, he was part of the so-called Ultimate universe, a dimension parallel to the mainstream Marvel world that was more narratively experimental. There, Peter died and Miles took up the Spider-mantle. When the Ultimate imprint ended in 2016, Miles was ported over to the conventional Marvel universe, where he’s played second fiddle to Peter but still held the spotlight in his own monthly adventures.

This is a big week for him. A much-anticipated new Marvel Comics series about Miles launched on Wednesday — and, notably, it’s the first Miles solo series to be written by a person of color, Saladin Ahmed. Even more remarkable is his big-screen debut: He’s the star of the critically acclaimed animated feature Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. These events are the culmination of a remarkable seven-odd years in which the character has gone from nonexistence to being a megapopular comics icon. But there’s a paradox at the heart of Miles Morales, one that his legions of fans — especially fans of color — hope these newfound opportunities will resolve. Put simply, Miles is the rare character who is largely beloved for his potential more than for his existing stories, especially when it comes to the matter of race.

The grievances that Miles’s adherents have with the character’s portrayal run the gamut from specific narrative points to general social tone-deafness on the part of the people who bring the character to life. When I ask Miles acolyte Anthony Otero how he felt when he first learned that there would be a Spider-Man who, like him, is African-American and Puerto Rican, he waxes nostalgic: “It made me feel phenomenal,” he recalls. That was then, this is now. “I still love the character, don’t get me wrong,” he says, “but it’s the way he’s written that I’m not a fan of.”

Something that Miles fans cited over and over again to me was their love-hate relationship with the character’s co-creator, writer Brian Michael Bendis. One of the most accomplished and influential scribes in the history of the superhero genre, Bendis had been the primary writer of Spider-Man’s Ultimate-universe adventures from their inception in 2000. He couldn’t be reached for this story, but he told me a few years ago in an interview for my feature on the Ultimate experiment that Miles’s origin lay in an official creative retreat held by Marvel around the turn of the decade. The topic of conversation turned to an evaluation of what the Ultimate team had done well or poorly over the years.

“In those conversations of what we did right or wrong, we’d come about the idea of Peter Parker being of a different race,” Bendis, who is white, recalled. “That if you really look at the origin, there’s no reason that character wouldn’t be of color — the fact that maybe it makes more sense.” After all, Peter comes from New York’s outer boroughs, which are astoundingly diverse in the present era. So the decision was made to shake things up by giving Ultimate Peter a hero’s death (he comes full circle from failing to save his Uncle Ben by succeeding in saving his Aunt May) and having Miles take over with the help of Peter’s allies soon afterward. “No one was asking for Miles, and you’re asking Miles to replace in people’s hearts something they really liked and that you took away from them,” Bendis said. “That historically doesn’t always work. In fact, it rarely ever does.”

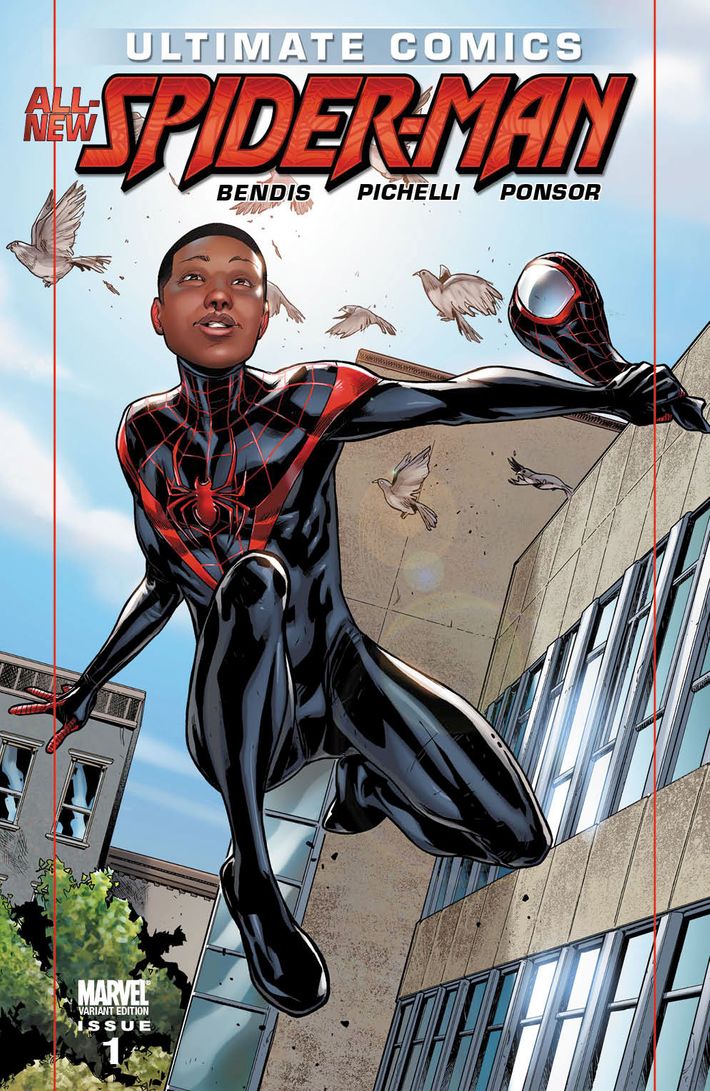

In this case, it did work. Co-created by artist Sara Pichelli, Miles made a debut cameo in a comic called Ultimate Fallout, then swung into his own title, Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man. Sales spiked and fans were abuzz about this somewhat radical development. Fan and former Marvel employee Bon Alimagno told me about his feelings upon reading Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man No. 1: “What I remember about reading it is that I was finding a new home within my Marvel fandom,” he says. As a Filipino-American comics reader, he felt a kinship with this fictional kid of color who was making such a splash. “A lot of that is a credit to the way Bendis writes his stories.”

Bendis was Miles’s primary writer from his first appearance up to Bendis’s amicable departure from Marvel earlier this year. In that time, he and his artistic collaborators crafted tales in which Miles struggled with self-doubt and the burden of legacy, gradually growing in confidence thanks to his skills and instincts, as well as the support of a wide and diverse circle of companions, ranging from his Puerto Rican mother to his Asian-American best friend, Ganke.

Devotees I spoke to repeatedly identified a trio of stories as highlights: his origin saga, wherein he finds out his uncle is supervillain the Prowler and witnesses his death; the one where Miles fights Ultimate Venom, who kills his mom; and the interdimensional crossover, Spider-Men, in which the mainstream Peter Parker teams up with Miles. There was also praise for a cute moment in the mega-event mini-series Secret Wars, written by Jonathan Hickman, in which Miles saves the multiverse by feeding a supervillain a cheeseburger.

However, that’s about it, when it comes to favored comics stories from before this week. Indeed, readers tended to get most animated not while talking about the yarns they liked, but rather about the ones that ticked them off. Some disliked the death of Miles’s mom, feeling that it was a gratuitous example of “fridging,” the phenomenon in which female characters are killed off as a way of motivating a male hero. Others took issue with the fact that Miles’s black father and uncle were both portrayed as criminals or ex-criminals. Even more people were pissed about the fact that, once he was incorporated into the mainstream Marvel universe, he lost a lot of his mojo by virtue of being the junior Spidey. Most just felt that Miles’s stories were way duller than they had hoped they’d be when they first fell in love with the idea of the character.

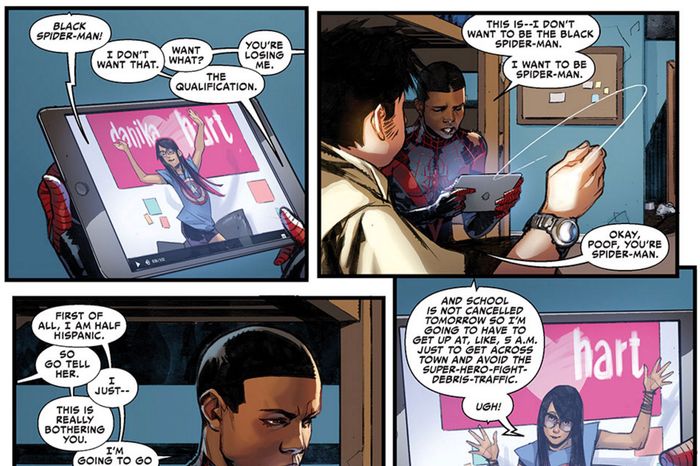

But one moment particularly drove people up a tree. In the second issue of 2016’s rebooted and Bendis-written Spider-Man — the first monthly series that Miles starred in after his merging into the main Marvel dimension — a vlogging celebrity sees through a gap in Miles’s costume and excitedly records a video about how there’s a “black Spider-Man” and that he’s “def color” (an odd bit of phrasing). Miles bristles at the designation while watching the video with Ganke. “I don’t want to be the black Spider-Man,” Miles says. “I want to be Spider-Man.”

Right away, there was a significant backlash to the storytelling choice. As comics critic J.A. Micheline put it on Twitter, “[H]eads up white writers: don’t write characters of color whose take is ‘I don’t want to be defined by my race.’” A subsequent tweet followed, reading, “Even if that is a feeling that some/many PoC have, think for a fucking second about the power dynamics involved in you doing that.”

That bit of dialogue still stings for lots of Miles’s devotees, especially nonwhite ones. “It was tone-deaf,” says Jonathan Hurrell. “It just seemed off, in a way.” Alexis Sanchez, co-founder of the site Latinx Geeks, agrees: “As a person of color, as a Latinx person, I know that being called the whatever-race superhero — we don’t see it as a negative thing because you’re kind of taking this prominent position,” she says. She also takes issue with the fact that, in that same scene, Miles describes himself as “half Hispanic.” “Most likely, he’d say ‘Latino,’ but more likely, he’d say ‘Puerto Rican,’” she opines.

That gets at another problem that Miles’s fans have with his portrayals: the perceived insufficiencies of the way his Latinx-ness has historically been depicted. “Throughout Bendis’s run with Miles, there has been no real look at his Latinx identity,” says Alejandro Jimenez, a writer who once penned an essay on the topic. “When they draw a meal, it’s always meatloaf and mashed potatoes and peas despite the fact that it’s clear his mom is cooking and his mom is Puerto Rican. There’s almost no Spanish spoken in the book other than by his abuela, and that Spanish is really weird. I don’t mean you need to do certain things to be Latinx or Hispanic, but when a white person is writing this, you need to think critically about what is actually being said and done and put on paper.”

Ergo the cautious optimism about Ahmed’s new comics run with Miles. The writer is a vocal and insightful analyst of issues relating to race and says he wants to bring those ideas into his work on the series. “At some point, Miles should be written by an Afro-Latino writer,” Ahmed tells me. “I try to know my limitations. But, in plain language, there will be a bit more to that stuff and his Puerto Rican side, and I think my Miles will definitely be cognizant and embracing of his blackness.” The first issue is out and it features Miles speaking Spanish and briefly commiserating with his mom about the detention of immigrant children. It’s not a ton, but it’s a start.

There’s another bright spot that has emerged in recent months: Insomniac Games’ acclaimed PS4 video game Marvel’s Spider-Man, which features Miles in its story, occasionally as a playable character. Insomniac’s creative director, Bryan Intihar, is proud of their decision to include him. “A lot of people identify themselves with Miles these days, and seeing that in an entertainment property is pretty powerful,” Intihar tells me. “We’re representing them, hopefully in the right way.”

If the sampling of fans I spoke to are any indicator, they’ve succeeded, even though there’s not much in the way of direct interrogation of Miles’s racial identity in the game. “Insomniac did a really good job incorporating Miles into everything and making him more common for people to know,” says Terrence Sage. “This is probably people’s first real — if they don’t read comic books — moment of, ‘Oh, so this is Miles and he’s a Spider-Man, too.’ They’re making him more commonplace everywhere now.”

That’s true, and nowhere more than in Into the Spider-Verse. The film features a team of Spider-powered heroes, but Miles is very clearly the lead character, stepping into the crosshatched long underwear after his universe’s Peter Parker dies. According to the movie’s directors, Miles has been the intended star going back to the original treatment from filmmakers Phil Lord and Christopher Miller. Per co-director Bob Persichetti: “When Sony approached them and said, ‘Hey, would you guys be interested in doing an animated Spider-Man film?’ they initially said no, and they took a couple of days and came back and they said, ‘Actually, we’d like to change that answer. We’ll do it if we can tell the story of Miles Morales.’ And the studio said yes. So he really became the catalyst for everything else that was in the movie.”

When it came to the delicate matter of race in the film, the creative team opted to leave everything unspoken. “Miles’s family dynamic presented us with such a rich base to build story on and character on that I think we handled it just by diving into that and trying to make that feel textured and as authentic as we could,” says co-director Peter Ramsey, who is a person of color. “It erased a lot of the burden about having to make any greater statement about race because simply portraying characters of color in more than two dimensions and getting past the usual tropes and issues helped us say, ‘Hey, it’s a story about people.’ Which is, to me, a statement in and of itself when it comes with dealing with characters of color. That’s all audiences of color want. We don’t want to keep watching the problem of the week, or stories about ‘Isn’t it so tragic that you happen to be this skin color?’ We want to see stories about real people that have the depth and the power and the subtlety of any other story you’d see in the mainstream.”

Sure enough, Miles’s background is at once very visible and wholly hidden in Into the Spider-Verse. He speaks a little bit of Spanish in the film, but for the most part, his racial identity is never addressed as either a boon or a hindrance. If you’re looking for a complex investigation of ethnic dynamics, you won’t find it. But what you will find is the first truly great story to star Miles Morales. I won’t spoil any of the plot points, but suffice it to say that Into the Spider-Verse is arguably the best Spider-Man movie to date, and Miles’s unique mix of shyness and burgeoning sense of duty shines through in ways that make him a delight to watch.

The road to this moment has been rocky, to be sure. There’s an uncharitable way to assess Miles’s awkward first few years of existence, summed up by Jimenez: “If you didn’t have the movie coming out and Saladin Ahmed writing the new book, you could very much look back on it and be like, ‘Marvel did this wild publicity stunt for eight years where they said they were gonna have a black and Puerto Rican Spider-Man and then killed him off without him ever appearing,’” he says. In other words, he doesn’t think Marvel, prior to the movie and the Ahmed run, had done a good job of enacting meaningful representation. He remains somewhat optimistic, if acerbic, adding, “I appreciate what Bendis has done in introducing Miles Morales, and I’m looking forward to seeing someone else give him a definitive run on the character.”

But if you want to be more generous, you can simply say that Miles’s journey has only just begun. Seven years is a short time in superhero fiction, and the character’s explosion in popularity in that span is remarkable: Just take a walk at any comic con and you’ll find many people in Miles’s distinctively colored costume, which one certainly can’t say for most non-Deadpool superheroes introduced in the past 25-odd years. Clearly, something profound resonates with his fans, something that transcends their problems with the specifics of his characterization. In some ways, Walter Mosley’s prophecy of a black Spider-Man has come true, and now it’s just a matter of whether the gatekeepers at Marvel know what to do with him.

“Whether you are African-American, Latino, of mixed race, or whatever you might be, I think everyone can find something to relate to with Miles because of his moral center,” Alimagno says. “But especially people of color can, because someone who still retains that moral center despite everything else going on around him? That’s such a special story to tell.”