Once again, Vulture is speaking to the screenwriters behind the awards season’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. For this installment, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse writers Rodney Rothman and Phil Lord talk through the introduction of Miles Morales, the half-black, half–Puerto Rican teen stepping into Spider-Man’s suit.

Miles Morales, for fans of comic books and Spider-Man, is very well known. But for people outside of that world, he’s not very well known. With Into the Spider-Verse, we’re introducing a character who our audience already knows is going to become a new Spider-Man. But the audience loves Peter Parker, the Spider-Man they’ve got. It’s a challenging introduction of a character: Our movie doesn’t work if you don’t fall in love with Miles Morales.

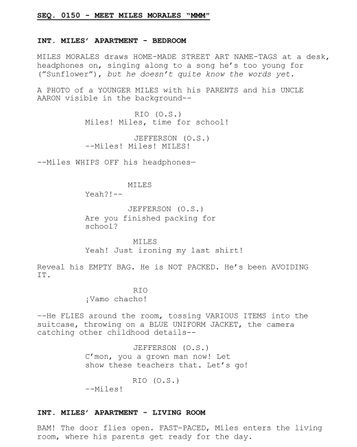

We open the movie with a montage that introduces the real Spider-Man. The scale of that scene is enormous. It’s like seeing an entire superhero movie in 45 seconds, guided by this very confident narrator. Then we cut to Miles, and things slow down a lot. In an elegant script, everything is deliberate, and everything is a microcosm for something larger: When you meet Miles, we see him singing a song with headphones on. We made a very deliberate choice to spend the first couple of minutes we’re with Miles really just watching him. We wanted Miles to be kind of lovable. We see him drawing and making stickers; we’re establishing that he’s a creative person, he’s an artist, who is able to create without feeling self-conscious or encumbered.

The most important thing for this scene to communicate is that Spider-Man, as a character, is always punching up. In Miles, we have a kid who’s not ready — he’s not ready for school; he’s not ready for this mission. He doesn’t have all the tools, but he has spirit, and we fall for him because of that. We start the movie looking at Miles, and then we end it with him looking right at us.

We needed Miles to score a foolproof laugh at the beginning of the movie, right when you meet him. There aren’t exactly jokes in this stretch, or any clever lines. It’s just what a reasonably clever kid would say. We had this idea that if he sang a song that was out of his register, it would make the audience laugh. It got a big laugh in the preview screening a year ago, but there was one problem: The song we initially used was the Donald Glover song “Redbone,” and we liked the double-layered joke of opening with a Donald Glover song because of his history with Spider-Man. “Redbone” killed … until Get Out premiered.

It was critical that the song gag landed. We had a feeling it was because people knew the song, and they knew how he was messing it up. We were in big trouble when we couldn’t use it anymore — we needed to replace one of the greatest songs of the year, and we had to do it in time to spend the three months we would need to animate that shot. It turns out “Sunflower” is a massive hit song. We heard it as part of a batch of songs that Republic Records presented to us.

We also liked the metaphor this presents: Miles is singing a song that theoretically he’s a little too young for and he doesn’t know the words yet. That’s the metaphor we’re going to be working with for most of the rest of the movie. He’s going to be asked to step into shoes that he feels he’s not ready for, he’s not going to know the words, and he’s going to feel very self-conscious and nervous about that.

With Jefferson, we need to convey the authority he has in Miles’s life. His lines are delivered from either off camera, or passing. In a very subtle way, there’s a bit of a disconnect between these characters: Miles and his dad talk to each other, but they don’t necessarily look at each other, or face each other. Jefferson is a character who’s searching for a way to communicate with his son. This line — “you’re a grown man now” — was improvised by Brian.

Jeff and Rio are both helicopter parents in some ways. We were always riding a line, we didn’t want Jeff to feel punitive or naggy. We always wanted him to seem like he was a good dad.

We had to have Spanish in this scene. We worked really hard with Shameik [Moore] and Luna [Velez] to have enough Spanish in there that felt credible and that didn’t alienate English speakers when they heard it. It was important that it wasn’t subtitled, that it felt completely normal, and was never presented as foreign or other.

Sometimes we overdid it. And at one point we underdid it. We spent a lot of time fine-tuning that stuff. Even in recording sessions where sometimes Rodney would be on the phone with his mom, and Luna would be on the phone with hers, and we’d be saying, “What would you say if I didn’t do my homework, and you were going to call me out?”

We tried a lot of different versions of this scene, but sometimes the most down-the-middle structure works the best. A lot of these sequences were grounded in conversations we were having about how a lot of the characters in the movie were fighting against inevitable change, and were seeking to go back to a comfortable place in the past that didn’t really exist anymore. That was the intention behind Miles and his old school, and wanting to go back to it. We decided that Miles’s school was around the corner from his house, because it let us say a lot of stuff very quickly.

The initial versions of this scene, in some ways, hit a lot of the same things but in a different order. You saw Miles hanging out a lot with a specific group of friends that we no longer meet specifically. There was a dinner-table scene with the parents, and a lot of the dynamic of that was eventually moved to the scene where he drives to school with his dad. You had stuff about how Jefferson feels about Spider-Man. In those drafts, the movie started with him telling his parents that he decided to quit school.

You don’t get the sense that Miles is Mr. Popular, but you definitely get the sense that he’s a well-liked kid who has history and rapport with the people around him. In some ways we started to draft a lot on Shameik, and his charm. This is just a piece of flavor that popped up, between the writing and the recording sessions. Miles is not in control of his powers; it’s almost like setting up what’s to come. He is a charming kid. He is starting to make connections with other people that may or may not be romantic; it’s unclear. He’s capable of getting the connection, but he just isn’t quite in control of what he’s doing yet.

The stickers that Miles works on came from Bob Persichetti and his rebellious, street-art-skateboarder past. In the initial treatment, we wanted him to have something that was a little lie that he would keep from his parents, because it felt like a good microcosm of the big lie that he has to keep from them, going forward into the next stage of his life. What’s cool with the stickers, too, is that they literally say “My name is.” It very uniquely set up that Miles was someone who was still searching for himself and identity and wasn’t quite sure who he was, and was almost trying out different versions of who he was, graphically, on these stickers.

There were many versions of this scene, even in its current structure. We tried over and over again to write more jokes for Miles. Beyond meeting Miles, this first scene with him is about mapping out the visual contours of what you’re doing, and the tonal contours of what you’re doing. You’re conveying the overture for your whole movie, and the audience is paying attention. Sometimes if you don’t establish that stuff early enough, it feels jarring later on if you take a sharp turn and do something that you haven’t set up as one of the colors you’re playing with. A lot of jokes just didn’t work. They either felt fake, or written. So we just said, “Forget it.” All we want to do is fall in love with this kid, fall in love with his family, and convey a couple of very simple things. The kid feels a little overwhelmed; he’s not prepared. He’s a regular kid who fibs to his parents, parents who have very high expectations of him because they love him and are trying to do as much as they can to help him. And, of course, we had to do all that in 45 seconds.

Below read the scripted version of the scene:

Now see how the scene plays out in the finished film: