When Paul Harding won the Pulitzer Prize for Tinkers at the age of 42, it was one of the biggest surprises in the history of American letters. The last time a small-press book won was nearly three decades earlier ÔÇö John Kennedy TooleÔÇÖs A Confederacy of Dunces. Unlike Dunces, Tinkers was no legendary posthumous epic; it was a quiet debut about a dying New England clockmaker, rejected by a handful of agents and relegated to a drawer before tiny Bellevue Literary Press paid Harding $1,000 for it. In the 15 months before the prize was announced, buzz from sales reps, independent booksellers, and NPR helped sell a respectable 10,000 copies of the book. But in April 2010, Harding went from being a writer with a small but devoted following to the envy and great hope of every aspiring novelist. The New York Times headlined its profile┬áÔÇ£Mr. Cinderella: From Rejection Notes to the Pulitzer.ÔÇØ Tinkers has sold 570,000 copies and counting across all formats. To commemorate the tenth anniversary of its publication, this month Bellevue released an anniversary edition with a foreword by HardingÔÇÖs mentor, Marilynne Robinson.

I played a small, accidental role in the improbable rise of Tinkers. At the time, I worked at RiverRun Bookstore in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and I picked up a copy on the strength of a blurb from Robinson and the stark white cover. I still remember reading the book in what felt like a fevered trance. Everything around me faded away as I sunk into the ÔÇ£quietÔÇØ novel, which starts with a man on his deathbed. I told everyone I met about it, including Rebecca Pepper Sinkler, who, unbeknownst to me, was the head of the Pulitzer fiction jury that year.

Curious about how the award had (and hadnÔÇÖt) changed HardingÔÇÖs life, I met him recently in a brightly lit Starbucks in Southampton, New York, not far from a Stony Brook campus where he is now a tenured professor. He looks the part: Holding a paper cup of coffee, he folds his eyeglasses over the center of his V-neck sweater and picks up the story of his career.

Harding had written parts of Tinkers on the backs of sales receipts and other scraps, working it over for years before selling it. His oldest son had chronic ear infections, and Harding resorted to driving around town to calm him down. ÔÇ£The second he fell asleep, IÔÇÖd pull over and write a sentence at a time.ÔÇØ His only hope was that it would one day become a book.

At every stage of its life, Tinkers gave new meaning to the publishing term of art known as ÔÇ£hand-selling.ÔÇØ Turtle Point PressÔÇÖs Jonathan Rabinowitz gave the manuscript to Erika Goldman of Bellevue Literary Press ÔÇö named for the medical institution that housed the tiny publisher at the time. Lise Solomon, a West Coast sales rep, read a galley and urged booksellers to take a look. Sheryl Cotleur, then a buyer for the Bay Area mini-chain Book Passage,┬áasked Goldman to print special hardcovers for their First Editions Club. ÔÇ£It just is a stunning experience to read it,ÔÇØ Cotleur says now. ÔÇ£It gets you on all levels: emotional, visual, intellectual.ÔÇØ

The Pulitzer tends to go to fiction with heavy marketing behind it ÔÇö the kind that only a handful of conglomerates can afford. Not only was Tinkers born in a one-room shop in a hospital; it wasnÔÇÖt even reviewed in the Times. ÔÇ£It felt like a win for everybody along the way,ÔÇØ says Goldman. ÔÇ£For the readers who loved it, for the young writers who never felt like they could break through, for the small independent publishing community, for every individual who loves books.ÔÇØ It also helped Bellevue Press survive.

On the day the Pulitzers were announced, Harding was teaching at the Iowa WritersÔÇÖ Workshop. When he found out, he ran to his former teacher Marilynne RobinsonÔÇÖs classroom to share the news. Her novel, Gilead, had won the Pulitzer five years earlier. ÔÇ£She told me: ÔÇÿItÔÇÖs the American equivalent of a knighthood. ItÔÇÖs your title now: Pulitzer PrizeÔÇôwinning author.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a strange kind of phenomenon thatÔÇÖs sort of there every single day,ÔÇØ Harding says now. ÔÇ£But as a writer, you canÔÇÖt think about it all. You have to think about whatÔÇÖs next.ÔÇØ

The common narrative about sudden fame is that there are two ways to go ÔÇö rocketing ever upward, or plummeting under the weight of expectations. In truth, life carries on just as it did before. Harding had already known this, because the Pulitzer wasnÔÇÖt his first brush with stardom. Prior to becoming an author, he was the drummer in the indie band Cold Water Flat; they toured the world, got signed by MCA. Broader recognition didnÔÇÖt pan out, but Harding knew all about having to appear in front of large crowds ÔÇö and having to ride the aftermath of a career high. ÔÇ£You become the protagonist for a little while, but you have to realize itÔÇÖs going to move on,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£You have to be still standing when it all calms down, and keep working, keep doing your writing.ÔÇØ

Music still informs HardingÔÇÖs life as an artist. ThereÔÇÖs a musicality to his prose, and a sense of intuitive expertise. He refers to something Sonny Rollins once said about practicing for 12 hours a day so that when he gets onstage, the music plays him. ÔÇ£My books are smarter than I am,ÔÇØ Harding says. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs one of the things I love about art: ItÔÇÖs improvisational.ÔÇØ For him, the ideal stage of writing is when ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm not actually thinking up and assigning to it, IÔÇÖm just taking the dictation.ÔÇØ

That process was already well underway on HardingÔÇÖs next book when he won the Pulitzer. Cotleur, the bookseller whoÔÇÖd helped boost Tinkers, had also shared it with her Random House rep, which led to publisher Susan Kamil signing Harding for a two-book deal; he was, once again, a major-label player. Enon, a sort of sequel to Tinkers set in the same landscape, follows the grandson of the first bookÔÇÖs protagonist as he grieves for his daughter.┬áHarding says his second novel was seen as more polarizing than his first because it was so dark. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt think itÔÇÖs as dark a book as people think it is,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£I think itÔÇÖs funnier.ÔÇØ Because it was treated like a big commercial release, its reception was a different experience, but somewhere along the way Harding realized that he needed to stop paying attention to reviews and the business side of publishing. ÔÇ£My job,ÔÇØ he says, ÔÇ£is to think about art.ÔÇØ

Harding published a reflection this week that sheds some light on how hes managed to stay grounded post-Pulitzer. It was those early Tinkers rejections  followed by the faith put in him by non-conglomerates  that steeled him against commercial pressures. Rejection  freed me from thinking about publishing, he wrote. The din of the market and publication muted, consciousness itself came into finer, deeper resolution.

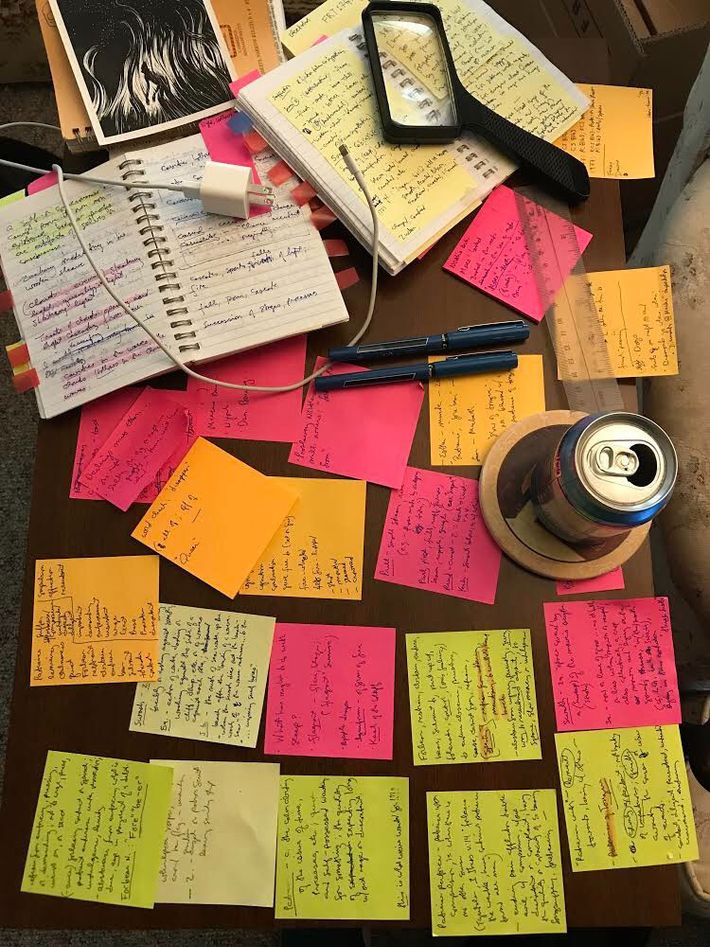

Harding equates writing to working on a watch. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm trying to make every sentence pages deep but absolutely lucid,ÔÇØ he says. He describes his new book-in-progress (currently titled Island) as a combination of Tinkers and Enon, written mostly on Post-it notes ÔÇö a modest step up from old receipts. Harding was inspired by a story he came across about a racially integrated settlement on Malaga Island, off of Portland, Maine. In 1912, the state evicted the residents, partly on the grounds of eugenics (they were allegedly inbred). Around the same time, the first International Eugenics Congress met in London.

Like Marilynne Robinson, Harding makes his fictional history feel both fully present and fully relevant. ┬áIn her foreword for the new edition of Tinkers, Robinson writes: ÔÇ£Learning to write is above all a matter of learning to discipline attention and to enjoy the aptness of language for the work of making a new report about the timeless world.ÔÇØ

While working on the latest manuscript, Harding would wake up in the morning, put a record on, and pore over ten books at a time ÔÇö Shakespeare, theology, philosophy, as well as 20 volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary, a relic of the Old Testament seminar he inherited from Robinson.┬á The OED was particularly handy. While writing a scene in which a character goes out fishing, he wanted to figure out a new way to describe the water. When he looked up the the definition of sugar, he found what he was searching for: ÔÇ£There are all these different words for scorched sugar and burnt sugar, and the sugar pleats and it puckers and that sounds like the ocean, so I did this whole description of the ocean like liquid sugar: candied Atlantic ocean.ÔÇØ

Unlike Robinson ÔÇö who says she doesnÔÇÖt revise ÔÇö Harding is slow and scholarly, a magpie of references and discoveries. HeÔÇÖll go days without writing, but heÔÇÖs always thinking about it. It works for him. ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre here to make the greatest work of art you can,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs not pretentious. ItÔÇÖs pretentious to act like you did, but to want to! Why bother putting anything less than everything at stake?ÔÇØ

Nine years after winning the Pulitzer, Harding still gets 100 emails a day. He enjoys meeting people who read his books, but he also loves being a bit of a hermit, and is very adamant about not being on social media. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt even like talking on the phone,ÔÇØ he says. For now, he wants to focus on his students and his family and, of course, his writing. ÔÇ£I want my writing to get deeper and deeper, but denser and denser, and clearer and clearer.ÔÇØ