Jean-Michel Basquiat is returning to his East Village roots. For the first time in 37 years, the artist, who died at 27 in 1988, is having a major solo show in his old stomping grounds. On March 6, an exhibit of 70 works, including pick hits from private collections around the world, opens at the Brant Foundation’s posh new museum, at 421 East Sixth Street, between First Avenue and Avenue A.

The four-story building, an old Con Ed transformer plant and the former studio of Walter De Maria, is spitting distance from many of Basquiat’s famous early haunts, including the Fun Gallery on East 10th, where a blockbuster show that helped make his name opened in December 1982. Wrote critic Nicolas Moufarrege at the time, “Jean-Michel’s show at the Fun gallery was his best show yet. He was at home; the hanging was perfect, the paintings more authentic than ever.”

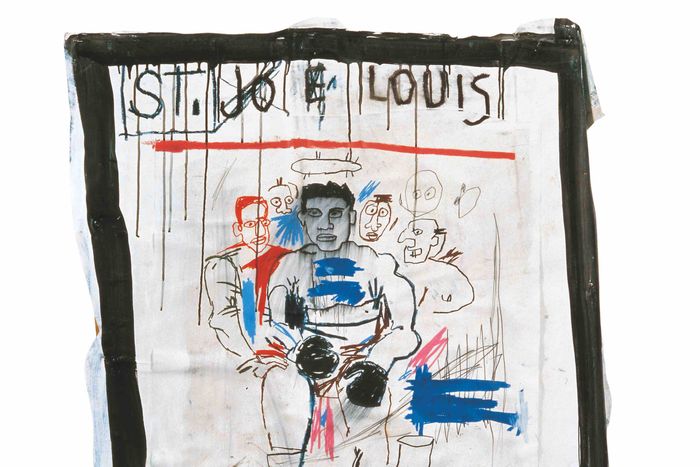

In 2019, the perfectly hung, “more than authentic” paintings are also more than burnished, radiating the artist’s posthumous global fame. The irony of Basquiat’s status then versus now would not have been lost on the art-world superstar, the most expensive American artist at auction in history, whose last record price, in 2017, was $110.5 million. It only adds to the irony that the painting that fetched that staggering sum, Untitled, 1982, purchased by Japanese collector Yusaku Maezawa, is proudly shown here along with several paintings first exhibited at Fun; the iconic Charles the First and Joe Louis Surrounded by Snakes (a not-so-veiled reference to the artist’s relationships with his dealers), which sold in 1982 for $6,000 to $10,000.

And, as gentrified and pricey as the East Village has become, the beautifully renovated multimillion-dollar building (which neighbors initially feared was an upscale condo development) is in notable contrast to the Mitchell-Lama affordable housing projects directly across the street. Basquiat was keenly sensitive to such disparity, as clearly seen in the multiple texts, titles, and references to racism, capitalism, consumerism, and greed, all amply evidenced in the work on display.

There is Irony of a Negro Policeman, one of his earliest paintings, exhibited at his first Soho show at the Annina Nosei gallery in 1981. The words “Hooverville,” “Papa Doc,” and “Five Cents” are among the words written on the canvas Museum Security (1983). A red door (1981) has only two words “Tar” (a reference to Tar-Baby and an anagram for art and rat) and “Pork.” “E Pluribus” sarcastically appears in the painting Per Capita. And most poignantly, “perishable” and “Nothing to be gained here,” a hobo phrase, can be seen in Untitled, 1987, done the year before Basquiat died.

Basquiat roamed and roomed throughout the East Village in the late ’70s, crashing with romantic flings and girlfriends at walk-ups ranging from East First Street where he lived with a major love interest, Suzanne Mallouk, depicted in the show as a sketchy scrawl (Self-Portrait With Suzanne, 1982) to East Third Street, and from East Sixth Street to East 12th Street, where he lived for six months between 1979 and 1980 with girlfriend Alexis Adler, leaving his writing on the wall, where it remained until being sold over 30 years later, including a door with a drawing of a car and the words “Famous Negro Athletes,” and a mural with the words “Olive Oyl.”

Basquiat also lived in the production offices of the film New York Beat, right above the Great Jones Café, when the movie was first being filmed in 1980–81. By that time Basquiat was already something of a celebrity, thanks to the cryptic Samo writings he and his high-school friend Al Diaz had scrawled all over downtown Manhattan. (Finally released 20 years later as Downtown 81, the film includes a shot of Basquiat writing “Origin of Cotton” on an East 10th Street wall.) Later, when he was rich and famous, he rented Andy Warhol’s loft across the street at 57 Great Jones Street, where he lived until his death.

Says Adler, “I think it’s fabulous that Basquiat has come back to the East Village. It’s amazing, because Jean’s not here, but his art lives on, and it’s come back home. I know he was born in Brooklyn, but this was home for him, whether it was 12th Street 6th or First or Third Street, this was his home; this was his turf.”

Ghosts of the old East Village remain: Gem Spa (Basquiat painted an eponymous piece, Gem Spa, in 1982) still stands on Second and St. Marks, as does the Pyramid Club, around the corner from the Brant on Avenue A. But CBGB, the celebrated Bowery punk club, is a specter of the past. Club 57, run by Ann Magnuson in a Polish Church on St. Marks Place, where Basquiat frequently hung out, is long gone. Unique Clothing Warehouse, on lower Broadway, where Basquiat briefly painted T-shirts, and Patricia Field, on East 8th Street, where he first painted on the hallway walls before painting on lab coats, sweatshirts, and disposable jumpsuits sold at her shop (which also mounted one of his first shows, full of mixed-media painted found objects) no longer exist.

In those days Basquiat created his “man-made” images on whatever he could get his hands on, from foam rubber to window frames to old TV sets and typewriters; these days his images are ubiquitous and mass-produced on everything from skateboards to iPhone covers to sneakers to kitchen towels. Rap artists like Jay-Z have memorialized him in lyrics; Swizz Beatz boasts a Basquiat tattoo.

The Brant Foundation show, a pared-down version of the Louis Vuitton Foundation retrospective in Paris, which closed at the end of January, will be the largest Basquiat show in New York since the one at Gagosian in 2013, which attracted some 6,000 visitors a day. Peter Brant first met Basquiat in 1984 through Andy Warhol. The first painting he bought, for between $45,000 and $50,000, The Price of Gasoline in the Third World (1982), is included in the show, as are two of his favorite works, Per Capita (1981) and Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982). He owns about 25 works and is still adding to his Basquiat collection. “These are the kind of artworks that you can look at over and over again and see something new every time. Basquiat is dealing with issues of great substance, and his playful way of handling language and its politics delivers it in a very powerful way.”

Brant wasn’t looking for a space to extend his foundation when he was initially shown the space, after being alerted to it by Dia Foundation founder Heiner Friedrich. Headquartered in Greenwich, Connecticut, the Brant Foundation is known for its exclusive exhibits of major contemporary artists, from Urs Fischer to the recent Francesco Clemente show. But, he says, “It was the perfect spot. And I knew before I closed on the deal that I was going to open it with a Basquiat show. There will always be Basquiat paintings in this building, but what is there now is a celebration of the best of his work.”

New York now boasts a private contemporary art museum on a scale with Miami’s long-established Rubell Family Collection and the Margulies Warehouse. The private museum model has become increasingly popular, in part for its potential tax benefits. (Manhattan’s other private art venues include Ronald Perelman’s Neue Galerie, the Donald Judd Foundation, the Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation, and the recently opened Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation, not far from the Brant, in a historic synagogue on Eldridge Street.) The Brant is free to the public, with hourly tickets that can be booked online.

Go-to gallery architect Richard Gluckman, who designed Brant’s Greenwich headquarters, was the obvious choice to repurpose the 100-year-old building. The stunning renovation retained the huge iron crane once used to hoist transformers, and created or restored large paned windows that afford spectacular views of the neighborhood, as well as glass panes on the stairwell that look directly into the galleries on each floor. The roof garden, landscaped by Maxwell Cox, has a reflecting pool that doubles as a skylight, casting shimmering light into the fourth-floor gallery.

The Basquiat show ranges from works on paper to major pieces, like the triptych Hollywood Africans, on loan from the Whitney and Gold Griot, on slatted wood, lent by the Broad Art Foundation. A massive, four-part 1984 piece Grillo, came from the Fondation Louis Vuitton. A second, magnificent large-scale skull (a favorite Basquiat motif), from the Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation, outshines the record-breaking iteration. And there are familiar pieces that pay homage to some of Basquiat’s idols, such as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Cassius Clay. The second floor of the foundation features a showstopping floor-to-ceiling installation of 16 paintings, all mounted on Basquiat’s early, characteristic crosshatched frames.

The show was curated by Dieter Buchhart, who has specialized in Basquiat exhibits over the last decade, including the recent retrospective at Louis Vuitton, as well as a show focused on Basquiat’s Xerox works opening at Nahmad Contemporary on March 12. “We bring Basquiat home to the area in downtown New York where he lived, and that’s the context, and people can feel it, and that’s the beauty of this show,” Buchhart says.

Or as Brooklyn Museum director Anne Pasternak, who’s lived in the neighborhood for years, aptly puts it, “We wouldn’t think about the East Village today without Basquiat, and the East Village helped form Basquiat. The two of them are so synergistic it would be impossible to remove one from the other.”

Phoebe Hoban is the author of Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art.