Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible. See his picks from last month.

For the family at the heart of her outlandish, distressing, and very much alive first novel, Arnett has chosen a profession that works on so many levels. Her narrator, Jessa-Lynn Morton, is carrying on the family business of taxidermy, even after her father kills himself (she discovers his body); her brother’s wife (also Jessa’s lover) skips town; and her mother expresses her grief by arranging her late husband’s animals into pornographic dioramas. Like her characters, Arnett makes art out of kitsch, converting the uncanniness of death (and Florida) into a monument to memory and queerness and love.

If the immigrants of the world were a nation, it would rival the U.S. in population. Mehta, author of the Pulitzer-finalist Mumbai history Maximum City, not only makes a forceful (and sadly necessary) defense of migrants’ benefit to their host nations; he weaves journalism, analysis, and memoir into a convincing master narrative. Whether driven by poverty, war, or climate change, immigrants are balancing out colonialism — earning reparations for what developed nations have taken from their ancestors. But unlike colonialism, migration benefits almost everyone, except for xenophobes and the faux-populists who exploit them.

By now we should be far enough into the canon of immigrant literature to know it is at least as fruitful as last century’s catalogues of suburban anomie. Dennis-Benn’s second novel forges new territory in the story of Patsy, an undocumented Jamaican mother who leaves her very young daughter behind in order to pursue a female love and, eventually, whatever remains of the American Dream. Meanwhile, her daughter, Tru, struggles back home with her estranged father and ambivalence about her own gender. A modern immigrant’s life is never simple; neither are Dennis-Benn’s path-breaking stories.

The prequel series to Ellroy’s original L.A. Quartet picks up steam in this jazzy, seedy second volume, which focuses not only on top cop Dudley Smith (his evil only nascent, like Anakin Skywalker’s in those other prequels) but also on the forensic scientist Hideo Ashida. In late 1941, we are a few weeks away from Roosevelt’s decision to intern Japanese Americans, including Ashida (if Smith can’t protect him). Ellroy is always so good at exposing America’s savagery; his portrait of the home front on the brink of a “good war” is as scathing as you’d expect.

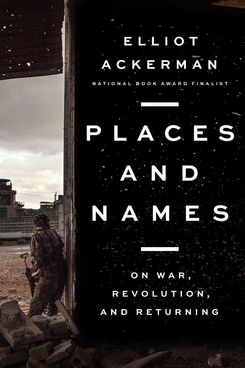

Ackerman is an acclaimed novelist as well as a decorated veteran of the Iraq War. His wartime experience has fed his tense, brilliant fiction, but this memoir in essays conveys the unvarnished truth of what he’s witnessed on the other side of America’s catastrophic errors. Threaded into the book are his friendships with Muslims who fought on different sides of recent wars in the Middle East. He pans out to a journalistic portrait of the conflicts before telescoping in — in a powerful essay built around his Silver Star commendation — to relive the Battle of Fallujah one last time.

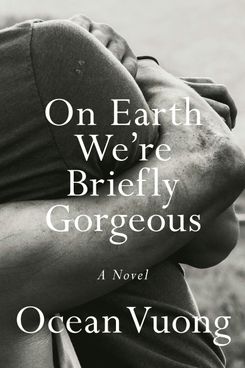

The young Vietnamese American poet imports the lyricism of verse into a novel that’s ostensibly a letter to the narrator’s mother, but really a diary of life on the margins of American society, coping with several kinds of exclusion as well as the third-generation trauma of a terrible war. The narrator, known as Little Dog, eventually falls in love with a so-called “redneck” who has some generational scars of his own. For all that Vuong has to say about history, queerness, and American culture, everything about his book feels specific and personal.

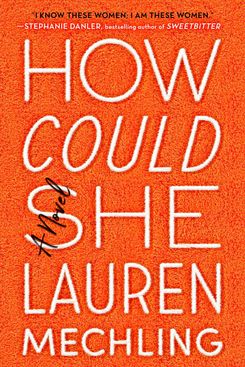

Some novels about the professional urban class succeed through the exaggerating alchemy of satire. Others are so sharp and honest about what is (yes) unlikeable in all of us that their realism cuts to the bone. Mechling’s novel about three women who met in magazine publishing isn’t nearly as meaty as, say, The Emperor’s Children, but it needn’t be. Geraldine has fallen on hard times after a breakup, while Sunny has found an enviable if shallow life, and Rachel has achieved a seemingly happy medium. All are in a position to help each other, if only they can get over their bullshit.