As the 2016 presidential election results rolled in, a common prediction from shell-shocked voters desperately searching for a silver lining was that the coming discord of the Trump era would at least usher in an amazing era for comedy. But in a twist nearly as jarring as Trump’s upset victory, comedy seems to have only gotten worse during his time in office. As SNL’ s joyless cold opens and the impotent “Sir, how dare you” finger-wagging of every late-night talk-show host prove, Donald Trump is nearly impossible to satirize.

One of the few outlets able to successfully spin comedy from the messiness of the Trump administration was MAD magazine, a staple of American satire for generations. But earlier this month, news broke that was decidedly unfunny: After 67 years and over 550 issues, MAD will soon stop publishing new material.

Though a gut punch to many who spent their formative years honing their comedic sensibilities in the magazine’s pages, it’s hard to view the decision as unreasonable. If a far-more-popular, all-digital satire institution like the Onion has been grappling with austerity measures, how could a periodical with tons of original art and writing commissioned for each issue, then printed and mailed to a handful of subscribers, stand a chance?

Nonetheless, MAD’s influence has rippled throughout pop culture since its inception and will undoubtedly continue to echo well into the future. Several recent articles have eulogized MAD as the “Boomer humor bible” and lauded its “incalculable influence on satire,” but overlooked in those write-ups are the many ways it impacted other areas of culture. So, as a farewell tribute to such a seminal humor publication, here’s an attempt at calculating the incalculable with some unexpected careers, projects, and moments the Usual Gang of Idiots influenced in some direct or roundabout way.

Weird Al Yankovic

It’s no secret or surprise that Mr. Yankovic is a MAD superfan. The parody musician, who credits the magazine as supremely influential in his comedic upbringing and the genesis of his weirdness, even had the honor of serving as MAD’s first guest editor in issue No. 533 in 2015. But beyond shaping Yankovic’s sense of humor, MAD also helped pave the road for his music career with something printed all the way back in 1961. This special-edition issue contained a songbook with parody lyrics to 57 popular songs of the era, meant to be sung over the originals. Composer Irving Berlin became so steamed about his song “A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody” being spun into the hypochondriac rant “Louella Schwartz Describes Her Malady” that he (and other music corporations with their own grievances) sued MAD’s publisher, E.C. Publications, Inc. The case made it all the way to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, before the judges (including Thurgood Marshall!) ruled in MAD’s favor, setting a major precedent for the legality of song parody.

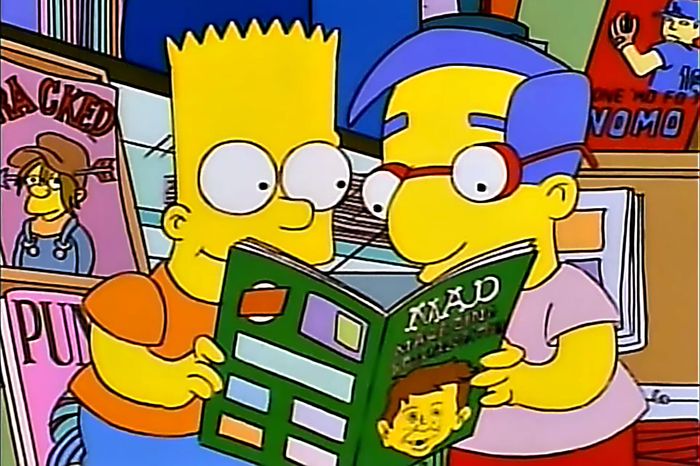

The Simpsons

If we were to chart the evolutionary history of Jewish comedy in America, MAD would likely sit right between Catskill comedians and the golden years of The Simpsons. The show has made numerous allusions to and jokes about MAD over the decades, often reverentially, as if to acknowledge the comedy genes it spliced into the DNA of everyone in the writers’ room. In The Simpsons: A Cultural History, writer Bill Oakley explained the writers’ shared sense of humor by noting that “everyone who was young between 1955 and 1975 read MAD, and that’s where your sense of humor came from.” Simpsons creator Matt Groening has often cited the humorous horror of the magazine’s early E.C. Comics era as influential to Life in Hell, his comics that predated the breakout animated series and the show’s annual Treehouse of Horror vignettes. Though the 2002 South Park episode “The Simpsons Already Did It” made the case that every conceivable story and gag has already occurred on that show, this old MAD cover insinuates that even some of their most iconic bits owe much to the humor mag.

Future Stars

Though it shared little more than name and some “Spy vs. Spy” segments with the publication it spun off of, Fox’s MADtv stealthily became a comedic powerhouse in its own right. Right from the pilot in 1995, the show’s audacious and often borderline-Dadaist sketches set it apart from its main competitor, Saturday Night Live. The strength of these scenes and the first-season cast made the show a hit with the alt-comedy crowd. Presumptions about the show serving as a mere farm league before the actors were called up to “better” shows quickly dissipated. Over its 15-season run, MADtv chugged along reliably, swinging for the fences and casting a shocking amount of future comedy royalty in the process. Icons like Mo Collins, Andy Daly, Taran Killam, Bobby Lee, and Ike Barinholtz all got early career boosts from the show. It also helped launch cast members Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele into their own series. Alfred E. Neuman deserved a shout-out in that Get Out Oscar acceptance speech, Jordan.

Adbusters

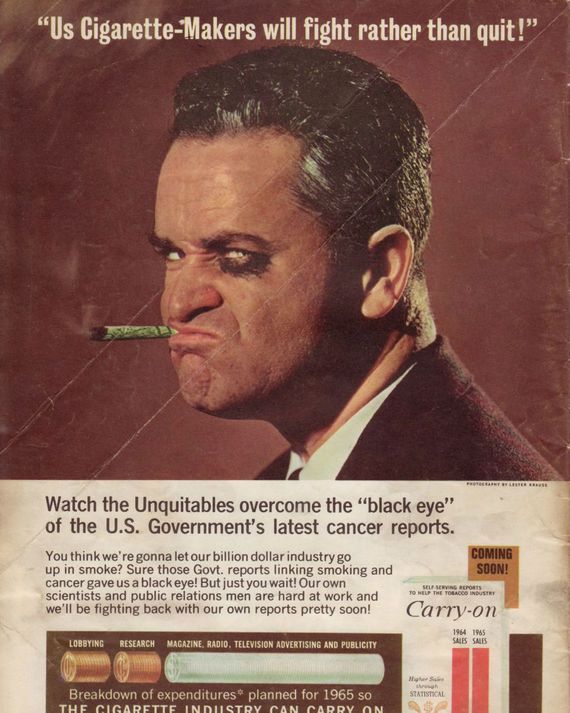

For its first 44 years in publication, MAD refused to sully its pages with advertisements, subsisting entirely on subscription fees during this era of peak popularity. In the places where ads might normally go, MAD printed sardonic spoofs of the era’s most popular print commercials. These gorgeous, full-page pieces went to great lengths to emulate the art direction, verbiage, and layouts of their real-world counterparts, often commissioning photo shoots or oil paintings in service of a punch line about how smoking kills. Though this take may sound too obvious to be funny today, MAD was actually one of the first pop-culture entities to take on Big Tobacco and its addictive products, and it did so in an era when every business and public space was shrouded in a thick haze of smoke. These parodies of real-world ads became so popular that, as noted in Frank Jacobs’s biography of MAD founder William Gaines, the staff began receiving requests from companies hoping to have their ads lampooned. These mock ads paved the way for the far more biting (and pretentious) black humor spoofs by Adbusters, the anti-consumerism periodical that emerged in the early ’80s and can still be seen today in many a college freshman dorm room.

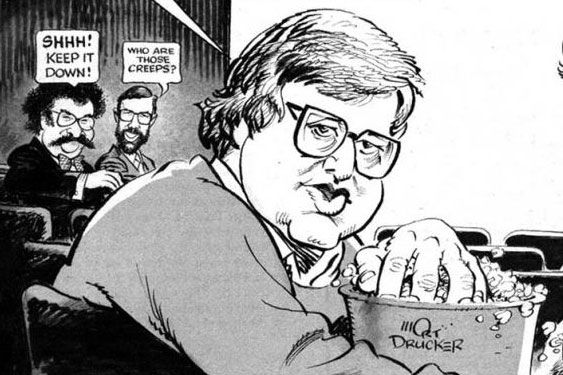

Roger Ebert

MAD’s 1998 movie-parody compilation issue opened with an unusually candid letter from cinema’s preeminent authority, Roger Ebert. In this forward, Ebert conveyed how MAD’s irreverent, fourth-wall-breaking lampoons of the latest theater fare gave him a crash course in filmmaking, inadvertently teaching him the vocation that would eventually earn him a Pulitzer.

“MAD’s parodies made me aware of the machine inside the skin — of the way a movie might look original on the outside, while inside it was just recycling the same dumb old formulas,” he wrote. “I did not read the magazine, I plundered it for clues to the universe. Studying each issue carefully, I learned about standard dialog and obligatory scenes, cardboard characters and giant gaps in plausibility …”

The admiration was mutual, and the Usual Gang of Idiots wrote and drew Ebert (and Gene Siskel) into numerous parodies over the years.

Politics

MAD’s lefty, counterculture politics were always an integral part of its content. It’s hard to overstate the brass it took to hire Cuban artist Antonio Prohías to mock the absurdities of espionage with “Spy vs. Spy” comics at the height of the Cold War. MAD was one of the first comedy fixtures to go after Nixon, and it even called out Trump’s lack of business acumen as early as 1992. That said, it didn’t shy away from mocking Democrats either. The staff painted themselves as idiots to never be taken seriously, allowing them to accrue fans from across the political spectrum without ever venturing into the pitfalls of “enlightened centrism.” Its universal appeal is best highlighted by the recent right-wing screeds blaming the PC police liberals for the magazine’s demise.

To bring us home in a way that encapsulates both MAD’s permanent fixture in the Zeitgeist and the inherent nonpartisan effect it has on political humor, we return to Donald Trump. In a May interview with Politico, the president compared Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg to MAD’s longtime dopey mascot, Alfred E. Neuman. Whether you regard Trump as the Antichrist or Second Coming, his schoolyard-bully zing was masterfully executed, earning laughs from across the political spectrum. Mayor Pete’s aloof comeback about having to Google Neuman, chalking his unfamiliarity up to “a generational” thing, only served to magnify the L he’d just taken.