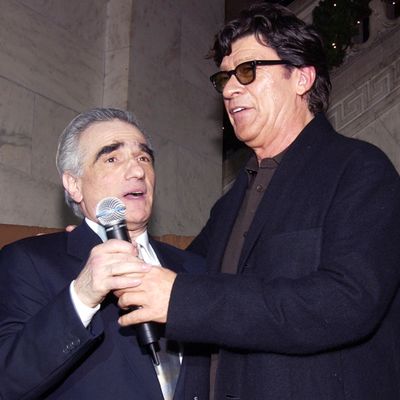

In Peter Biskind’s 1998 book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Martin Scorsese’s former flame Sandy Weintraub quips, “It’s a shame that Marty wasn’t gay. The best relationship he ever had was with Robbie.” The Robbie in question is, of course, Robbie Robertson, co-founder of the Band and a four-decade collaborator of Scorsese’s who produced and composed music for the soundtracks of Raging Bull, Casino, The Departed, and The Wolf of Wall Street, among others. Their relationship began around 1978, when Scorsese directed The Last Waltz, the documentary that captured the dissolution of the group that famously backed Bob Dylan. Robertson moved in to Scorsese’s house on Mulholland Drive shortly after, where days and nights were fueled by marathons of music listening and movie viewing. And cocaine. Lots and lots of cocaine.

Over 40 years later, Scorsese is releasing his most expensive film yet, The Irishman, an epic crime drama based on the book I Heard You Paint Houses, about an alleged mafia hitman named Frank “the Irishman” Sheeran (played by Robert De Niro). Robertson composed the film’s score and handpicked each needle drop, finding himself more and more fascinated by the outlaws at the heart of Scorsese’s story. So much so that listeners can hear the gritty stomp of “I Hear You Paint Houses,” mob slang for the process of hiring a hit man, on Robertson’s latest solo album, Sinematic. Ahead of The Irishman’s release on Netflix, Vulture spoke to Robertson about his immediate attraction to Scorsese, who gets the credit for some of their iconic music cues, and where his ongoing relationship with Dylan and the Band stands.

Have you always been attracted to villains and outlaws?

It comes from childhood. As a kid, I remember seeing movies like The Public Enemy, or a movie about Dillinger, and being blown away. I think there’s something in our DNA that draws us to Jesse James. We like Bonnie and Clyde — maybe we shouldn’t, but we do. I’m going to warn you about The Irishman: It’s different than any mob movie I’ve ever seen. It has a different rhythm, and leaves you with an unexpected feeling. There’s a lot of quiet talking about things that shouldn’t be going on. What I had to do with the score for the movie was to create a sound that I had never made before. It’s not supposed to be a crash-bang-shoot-’em-in-the-eyes kinda thing at all. It’s a different feeling, and I love it.

A lot of people will see the movie and say, “I thought there was gonna be more shooting!” They’ll be expecting Goodfellas, where Henry Hill was tweaked and everything was high energy. This is not that movie.

Did you ever actually experience the gangster lifestyle?

My Uncle Natie was like the Meyer Lansky of Canada. He didn’t try to pull me into anything that broke the law, but he tried to pull me into the mindset of the gangster traditions. He would tell me about what my blood father would have done, and would have been, if he hadn’t gotten killed. It was the Jewish tradition of people who operated just outside the law. They were in the whiskey business, and started out in bootlegging. They went legitimate, but you gotta crash through the gates to get legitimate, otherwise it takes forever. This whole lifestyle was relayed to me in a very attractive way, and there was something inside of me that I related to. I felt a connection to it, and in my bloodline, it’s a part of who I am. Early on, I was on Roulette Records, which was run by Morris Levy, who was a complete mobster. It was all around me, all the time, and it’s a wonder that I didn’t end up doing something that I would have regretted later.

Do you remember the first time you met Scorsese? Was there an immediate attraction to him as a person, and not just as a filmmaker?

The first time I met Marty was just after he made Mean Streets. Our road manager, Jon Taplin, after he had worked with us for awhile, told us he was leaving to produce movies. I said, “Oh, really? Just like that, huh?” He went off and produced Mean Streets. He told me that Marty was a really talented guy, and that there was an actor in Mean Streets who people thought was the real deal. He wanted me to see the movie, so they set up a screening for me. After, Marty approached me to say hello. That was our first meeting, and after seeing the movie, I thought, “This is a guy who does it his own way. This is a guy who makes magic.” I also immediately recognized that Robert De Niro was above and beyond, and an actor’s actor. Around that time, Marlon Brando said, “The new great actor has just come on the scene, and his name is Bob De Niro.” The next time I saw Marty was to talk about The Last Waltz.

During the experience of putting together The Last Waltz, I thought of Marty as part of my brotherhood. I immediately really, really liked him, and recognized him as such a special talent. When we lived together on Mulholland, there was a lot of work being done. It was a period in the culture that we were a part of that was really crazy, but nobody realized it at the time. We just thought of it as business as usual. He turned me on to so many movies, and I tried to turn him on to some wonderful music that he wouldn’t have discovered on his own.

In your first score discussions for The Irishman, what were your and Scorsese’s initial reference points?

It was a blank canvas. The film spans many decades, and we had song ideas that we wanted to use for the different periods. When we started breaking it down into time periods, it all grew from there. We also started thinking about what would work as counterpoint, or what would not be the obvious choice. That’s where we started, and when it came time to figure out the score, Marty said, “Rule number one is that it can’t sound like movie music.” I was doing music for a movie, but it couldn’t sound like movie music?! That eliminated a lot of possibilities, so I had to go to a musical headspace that I had never been before. It works beautifully in the movie.

Have you guys ever gotten into fights over the way a movie should sound? Any real heated arguments?

We’ve never had heated exchanges, but we’ve certainly had different points of view. Ultimately, we tend to recognize the value in what one of us was bringing to the table. Years ago, I did the score for The Color of Money. I had a whole idea about bringing a nice sleaziness to the music in this pool-hall world, and I wanted to use blues. I wanted to work with Gil Evans and Willie Dixon. I hadn’t seen the movie yet, and I don’t write or read music, so I put some stuff down on tape and sent them to Marty, with the idea of him telling me if it was going in the right direction. On the tapes, I just hummed a melody, accompanying myself on piano, guitar, and keyboard. I sent him these rough musical sketches, and Marty put them in the movie. I said, “No! That’s just a sketch of an idea. It’s not for use in the movie!” Marty said that they worked beautifully, but I was embarrassed because I wasn’t dressed. He was using naked music before I even had a chance to do my thing. Marty kept telling me that it was really working, and I’d be surprised in the end. He finally showed me the movie, and I thought, “Well, I’ll be damned.”

Let’s play a quick game. I’ll name a classic needle drop from Scorsese movies you worked on, and you tell me if it was your pick. “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from Casino?

Nope. That was Marty. He’s used Stones songs over the years because there’s such a raw energy that works with the raw energy that he’s trying to bring to the picture.

“I’m Shipping Up to Boston” from The Departed?

That was me. 100 percent. I just knew it worked, and Marty had never heard of Dropkick Murphys. He fell in love with it immediately, and that’s part of our working relationship. I’m still curious, and there’s always great music being made. I want to hear it. I’ve got my ears wide open all the time.

Has your creative process remained the same all these years? Is it about, as you mention in the documentary, trying to, “Catch yourself off-guard” to create?

I’ve found that when I sit down to work, sharpen my pencils, and get all my papers laid out, I can hit a wall. I can’t think of anything to write with those pencils. It’s not necessarily superstitious, but if I’m just walking around the room whistling, and I sit down at the piano and touch the keys, suddenly, it’s like, “Whoa! I wonder where this is going.” There’s a certain joy in that, a pleasure in the discovery. It’s like that in every element of the creative process for me.

In a perfect world, would the Band still be making music together?

Who’s to say? You can’t predict tomorrow, but I thought we would be. It just wasn’t in the cards, and I had to accept that. We started out so young, and it was such an amazing journey. We had such an incredible brotherhood that I wanted it to last forever. There’s only so much shit that you can put in a book or a film. The fact that I’ve lost three of my brothers is tremendously sad. I never thought I’d be looking out at the world without those guys walking the earth.

Van Morrison dueting on “I Hear You Paint Houses” feels like a no-brainer, but what about Glen Hansard, Derek Trucks, and Citizen Cope? Did you write Sinematic with these guests in mind?

Nothing was preconceived. It all just happened, and I love it. Sometimes, it doesn’t work out, so there’s a risk in collaboration. I was doing the background vocals on “Once Were Brothers” with J.S. Ondara and Citizen Cope, which doesn’t fit together at all. It’s beautiful, magical, and a different sound. When it connects in my imagination somewhere, and I can see it, it becomes like a movie to me. If I can see it, and it helps tell the story, then I know it’s true. I’ve known Glen Hansard for a while, and he’s an amazing talent. With Glen and Van Morrison, who are both from Ireland, It was just a coincidence that I happened to be working on The Irishman at the time. It was almost magical, because I wasn’t thinking about these connections going in. It just made perfect sense.

Did you ever find the blurring of fact and fiction in Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese distracting?

I thought it was really funny. I got the humor, and it’s a shame that the tour, and what they did on that tour, wasn’t really shared. To this day, I still haven’t had a chance to see Renaldo and Clara. I think Bob Dylan’s people finally decided that they needed to do something with that material, and they had a conversation about what they could add to it to make it something fresh and new. I enjoyed the idea that it was a complete put-on.

Are you still really close with Dylan?

We spoke about two or three weeks ago. We’re talking about some stuff, so we’ll see.

How is your mental headspace today? Are you happier than you’ve ever been?

I think so! I don’t want to jinx anything, but I’m having as good a time as I’ve ever had creatively. All this shit is going on, and most of the people from my generation are thinking about where they want to retire. I’ve got so much still on the table that I just have to do, and that keeps me very excited. That enthusiasm and excitement leads to a certain contentment and happiness.

This interview had been edited and condensed for clarity.