“This is the Sacred Grove, where my fancy friends come to play,” Stewart Copeland tells me within a minute of logging onto Zoom. No, he’s not beaming in from a magical wood filled with cymbals and snares: I’m getting an impromptu tour of the sun-soaked studio in his Los Angeles home, which frequently hosted his carousel of “chuckle buddies” before the pandemic began two years ago. “Since the apocalypse, I haven’t been doing very much. Before that, I had Snoop Dogg, Neil Peart, Ben Harper, and Stanley Clarke here, because the room is gorgeous,” he explained. “I have the largest collection of the cheapest instruments money can buy, and everything’s mic’d up.” There are a few cameras to the right; a few more to the left. Behind him, a timpani and a drum kit. “Every square foot of the room, there’s a mic on everything,” he added. “So I have these jams and then I cut them all up and put them on YouTube.”

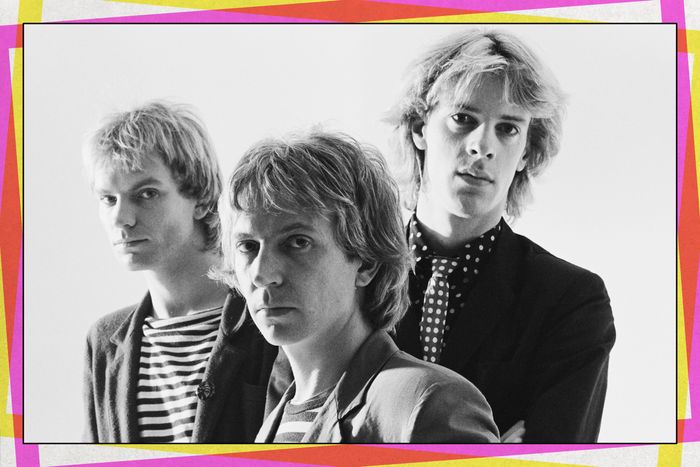

Copeland, a hell of an amiable guy, is resting in between some national-tour dates as a symphony-orchestra composer. He’s also celebrating a Grammy nomination for Best New Age Album, the kinetic Divine Tides with Ricky Kej. (“I would be the first drummer in history to get a New Age award,” he quipped.) But let’s be frank: You know Copeland for his work with the Police alongside guitarist Andy Summers and that guy named Gordon, a drummer whose cross-genre mastery and dynamic style somehow managed to make the power trio sound like a power sextet while buoying them as one of the biggest bands — if not the biggest band — of the ’80s. “Roxanne” has a tango edge because of him, “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” a frisky groove. And don’t even get us started on “Walking on the Moon,” which was sent from the heavens by the god of hi-hats. But why blather on when Copeland himself can talk about it all, which he does in our newest Superlatives.

Best song

It’s a tough choice, because I have personal favorites that I enjoy playing the most that mean something to me. Then there are the ones with the most pristine and cleverest compositions, where Sting really pulled it out of the bag and nailed it. Then other ones where the song wasn’t the best song he ever wrote, but the band made it great. There are different ways of picking a winner. So I’m going to go with just my own personal taste. “Bring on the Night” is the most beautiful song Sting ever wrote. The band arrangement of it is okay. It’s not even one that I particularly enjoy playing because it’s quite tricky rhythmically — it teeters on the edge. But it’s such a beautiful, poignant song. That’s the one that hits me the most emotionally — the music, the emotion in the chord progression, the message of the song, that feeling of bringing on the night. This day’s been hell, but let me have my tequila shot and let’s just change the subject. I know that feeling. I’m sure everybody knows that feeling.

Most spontaneous song

One evening after dinner, Andy was strumming his jazz chords and Sting said, “Hey, that’s interesting.” They both like jazz chords. Sting said, “I think I got a lyric for that.” They’re sitting there at the dinner table, and Sting’s pulling out his lyrics and making them fit to Andy’s chord progression. They’re kind of working out right there. Twenty feet away is my drum set, because the dining room had a great sound on Montserrat — my drums were set up in a separate building from the studio in the dining room. Andy was in the main big recording room with all of his amplifiers, and Sting was in the control room with just his bass and a microphone stand. So they’re working it out, and I’m kind of thinking about what the rhythm ought to be. They said, “Let’s record that,” and they walked downstairs and along the pathway into the studio. By the time they get in there with the engineer, I’ve walked 20 feet and am already on the drums banging away, but they can hear my open mics come through the speakers. They start up the song, and they play it down. The song’s called “Murder By Numbers.” That performance was the first time we ever even ran the song down, and it’s on the record.

But spontaneity was one of the seeds of the band’s destruction. In the early years, we were co-dependent, and we thrived off one another’s contributions. Andy had given me cool ideas for the drums, and I’d leap on it with enthusiasm, which actually went all the way through the band experience. Every time Sting pulled out a song, we leaped on it. They were just great songs. Whatever World War 18 was going on at the time, those songs were always great. But the spontaneous part became more difficult when Sting got more and more confident in getting hit after hit. Like any musician or artist, as you mature, you learn the craft of your gift and you get better at it. So he would write songs, and they’re fully formed in his mind — pristine perfection. By the way, he’s a pretty good arranger. The arrangements in his mind were perfect to him. Now, if I came at it with a different rhythm or Andy came at it with a different guitar part, that became more and more of a struggle for Sting to deal with, the idea that collaboration equals compromise, when he had such a perfect vision in his head. That spontaneity works against the pristine cathedral of perfection. I say this with respect, because he is that talented. The songs were perfect in his mind and would’ve been perfect out in the world that way.

So I don’t begrudge that at all, but it did make it very frustrating for Andy and me to get a word in edgewise. Or to be able to use the band as a creative outlet, which is why musicians play in bands, because you play in a band or become a musician to express what you have. It became more and more of a battle to work and collaborate. We all understand these factors now and don’t hold any grudges about it. We understand what it’s all about. It was all about how each of us had a very strong urge to express ourselves in the medium of the band. That’s one of the reasons why it’s a three-piece band — all three of us had high expectations that the band would be where we put all of our artistic chips.

Song you’d rerecord if given the chance

There is, but no one agrees with me. “Wrapped Around Your Finger.” Like all of the Police songs — unlike the first album and parts of the second album — I would hear a song and record my drum part 20 or so minutes later. Sting and Andy got a chance to redo all of their guitars and vocals and everything else. But the drum parts I played 20 minutes after hearing the song because Sting would only reveal them one at a time. Very clever technique. He would be like, “I got one more for you.” [Laughs.] So those drum parts are all very spontaneous. In a lot of places, I thought we were going to the chorus, but there’s another verse, so that affects the sound. I would change the rhythm thinking that we were going into that other part, but not so. Or it goes into the chorus, but I’m still playing what I thought was the verse because I’m not hearing the whole song. I’m only hearing Andy and Sting plunking on their instruments, bored, waiting for the drums again, and Sting’s singing some of the lyrics without any great commitment because they both know they’re going to redo everything. They’re just playing their part so that I can get to mine. Once I’ve got my part, then the fun begins. Then we go out and plan it on tour, and I figure out how to get from the chorus back to the verse. This is how I should do that.

I wish I’d done different things on “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” but it still kind of worked. Maybe I would’ve screwed it up. People say, “No, that’s a great performance,” but I can hear my hesitancy. I can hear that I wasn’t very comfortable in that rhythm there, but my drummer buddies tell me that’s what’s so cool about it, that it has an exploratory feel, so go figure. I got another one for you. The end of “Message in a Bottle.” I put one too many drum overdubs at the end. I went kind of ape crazy at the end. Too much crashy-bashy at the end of “Message in a Bottle,” I think nowadays. I would’ve cleaned that up. But then again, my tastes are not necessarily the zeitgeist. Sting had a much better idea of what normal people like.

Creepiest love song

You know the answer to that. Everyone knows the answer to that. “Every Breath You Take” is the creepiest. Who wouldn’t love seeing such a song being played at weddings as their wedding song? What’s not to love about that? “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” is pretty creepy as well. But you’re assuming that I listen to the words. I don’t. I’m just banging shit at the back of the stage. [Laughs.]

Song that exemplifies your hi-hat mastery

“Walking on the Moon.” That was where I also used the delay lines and the repeat echo, which creates these rhythms. I was hearing those as I’m playing off the repeat echo — the slap back, which is a different rhythm. It’s a dotted quarter-note away from what I’m playing. I would play with that and interact with it. Drummers like that spot.

The hi-hat is the upper level of the rhythm. There’s two layers of rhythm: One is the 16th-notes, or the fast notes, which you’ll normally hear on the cymbals or hi-hat. The other half of the rhythm is the backbeat and kick relationship, or the downbeat and the backbeat. The snare and the kick drum interact to create the meat of the rhythm. But the upper level, the hi-hat and the cymbals doing those 16th-notes — the faster patterns — are the connective tissue for the meat and potatoes of kick snare. It’s the interaction of those elements that make a rhythm what it is. The hi-hat contributes to the upper level. It’s a particularly useful instrument because it’s two cymbals pressed together, and how tightly they’re pressed together is controlled by your left foot. If you release your foot a little bit, it opens it up completely. So your left foot is controlling the texture of that upper-level rhythm with a high degree of expression. There’s a whole kind of vocabulary that you can put into that upper level of the rhythms.

Most underrated song

Actually, I’d say “Murder by Numbers.” Because it was a B-side. Whenever we played concerts, it was very popular. I play it now with my orchestra show and it’s very popular. I’m very proud of it. It didn’t get a chance, but it sort of achieved cult status in a way. Mind you, I’m forgetting Andy’s song, “Friends.” But my heart and soul doesn’t rest on the fate of one song.

Most overanalyzed drum part

“Spirits in the Material World” is the one where everyone says, “How the fuck do you do that?” I’m not even sure myself. The rhythm came from a little Casio sequence. You can’t buy them anymore. They’re too complicated now. You used to be able to get a little Casio about a foot long, and it had a little rhythm. I believe that Andy wrote “Spirits in the Material World” on that, but the rhythm has this uplifting vibe. It’s all up. There’s no down. It’s skating on the knife’s edge. It’s one of the most difficult songs. It’s the most simple, but it’s a scary song to play. Musicians fear it because it’s so easy to fuck up and land on the downbeat. Every musician, they can draw a breath. They need to know where one is. Unfortunately, I have a terrible blot on my personality, a scar in my spiritual tissue, which induces me to hide the one.

I realized later on that a drum break is actually a muscular thing. It’s a repetitive action, which gets very strenuous. To do the same action, even if it’s a little action, and keep doing it is tough. That’s why orchestras hate to play minimalist music — Philip Glass or Steve Reich, for instance, because they have to do the same thing without variation. So with a drum fill, all the muscles get reordered. Okay, now I’m back to that groove. I can do it. To get locked into that thing where there’s no variation is very, very fatiguing, and a drum fill is a way of relieving the fatigue of the repetitive action.

I learned a couple of things through the years when I was young and vigorous and when I went out there and suffered as a drummer for the first few dates. I discovered, by accident, preparation, which is practicing and getting fit. The Police once did a tour at the end of polo season, and I was super-fit from staying on a polo horse. That’s going to make you fit. We started rehearsing, and unlike what usually transpired, I leaped into those rehearsals with all the energy in the world. Let’s rehearse for another two more hours. A few years later, I discovered stretching and warm-up techniques so that by the third song I’m really up to cruising altitude. I learned that from an old jazz cat.

Drumming is really hard work. I recently learned something new. I could rehearse all day, all night, days on end, on the guitar. But on drums, I’m done by six. I am done. I got to get in the shower. I bring three T-shirts to rehearsals because it’s physical work. You’ve got to carry that band on your shoulders every foot down the highway. As a guitarist, most of the time, you’re just standing there looking handsome. I look at young Pete Townshend busting a sweat, and I think, Jesus Christ, it’s so obvious. The next time I saw Dave Grohl, I told him, “Come on man, fess up. Tell Taylor Hawkins that he’s working six times as hard as you are. You know it’s true. You’ve been there. You’re here. Come on Dave, fess up.” The guitarists, they never let on. When you’re playing guitar, you look at the drummer and it’s obvious. That guy is breaking a sweat. No guitarist or any other musician has ever fessed up.

Geekiest song for drummers

So, I have a story that relates to this. During one of our tours, I was playing “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” at every show. At a certain point in the tour, Sting said to me, “You know what? I never liked that drum. Why don’t you just leave a space there? That’d be really cool.” I said in response, “I’ll be hanged, drawn, and quartered.” [Laughs.] He says, “Nobody gives a fuck about that.” Are you kidding? In Drum World magazine, they write editorials about that drum fill. We’re kind of laughing and we’re pulling each other’s chains about it, rattling each other’s cages, as we are so fond of doing. So a couple of years go by, and now we’re on our reunion tour. A fan came up to us in Spain, and he’s got the Spanish version of Drum World magazine. He said, “Could you sign my magazine?” He opens it up, and there’s a page with that song and that drum fill. I’m sitting next to Sting at the bar. I turn to him and go, “Listen, you motherfucker. See that, you motherfucker?”

Album with the most esoteric musical influences

I would say they’re about equal in terms of influences. Not that I listen to the lyrics, but Sting’s world expanded beyond writing a love song for a pop group playing on a stage. He began to see the band, and albums, as being a way of expressing higher consciousness. He was always a deep reader, and he increasingly transitioned that into being a part of his repertoire with Zenyatta Mondatta. Synchronicity was a concept album, for God’s sake. Ghost in the Machine was in its own way too. So literary influences crept in there with the lyrics. Musically, the first album was derivative of the world. We were playing what we felt we needed to play to survive in the marketplace, which were rock songs and punk songs. Then, with every album when we established ourselves and grew more confident in our own material, the influences of the market and other bands we were listening to became less important. We’re all music fans, after all. We became less derivative as we got more confident.

It must be said that one of the main outside influences was reggae, which resonated for me because I grew up in the Middle East. With depth key rhythms and ballade rhythms, they have structurally similar foundational principles. That’s something I grew up with, so all the reggae drummers were an outside influence. Before that, it was Buddy Rich and Mitch Mitchell, but that was when I was a kid.

Most mispronounced album title

They all are. There’s no correct pronunciation for Zenyatta Mondatta. That’s a trick question. It’s a trick album title. [Laughs.] Reggatta de Blanc is tough. We never could agree among ourselves whether it should be Reg-att-a de Blanc or Rega-ta de Blanc, depending on how sophisticated the company you keep is. For the first three, we had that style of album titling. The last two were named after the central thesis of the songs that Sting wrote. In one case, it was Ghost in the Machine, after a book by that name. The other one was Synchronicity, which was the theories of Carl Jung. I only learned this later. I couldn’t give a rat’s ass about it at the time. There isn’t any correct pronunciation for our albums. You choose your own version and be superior.

Silliest Sting story

If there were such a story, I wouldn’t share it with anyone. The thing with Sting is that he’s a man of implacable dignity. He is absolutely not the person that many people think he is. He’s quiet. He’s quiet and deep, whereas I am noisy and shallow. He’s not a socialite. He’s not very good at small talk. He’s quite shy, in fact, and reserved. People often mistake that for arrogance or disinterest. It’s far from the truth — he actually laughs really easily, has a good sense of humor, but his persona is kind of dour. For some reason, when a camera goes on him, he goes into that face. When I see that, I think, Dude, come on. You’re not that guy. But he is a mystery wrapped in an enigma. We’re just creatures of a different feather. We love and admire each other. The bond we have, the shared history and everything, is a wonderful thing. But we’re just not birds of a feather. I’ve known him for 40 years and have no fucking idea what’s going on behind those baby blues.

Why Spyro: The Dragon was the best music you ever wrote

It has to do with the rate of work and the volume of material being produced. For four years, every summer, I produced a triple album of backing tracks quickly under the gun. I’d churn them and burn them. I would do three a day over two days and then the next day I’d come back and finish them. Bang, three more in the bank. You burn up any ideas you might have had in the cookie jar. You go straight to raw. With Spyro, I just had to keep going. I discovered that with quantity comes quality. Because you would think that it would all be very shallow and ill-considered and too facile. But, in fact, you get into a zone. You get into a sweet part where your subconscious and imagination starts producing. It’s like a muscle that you work, and it gets stronger. The momentum of creativity builds up. I think it’s because I didn’t have time for judgment or self-doubt or hesitancy. Every summer, I’d be doing Spyro and playing it with my kids. I have four boys and three girls, and it was just like a family in the ’50s watching The Jetsons. The whole family in there together, lit up by my music.

It’s a funny story. My kids go to private school on the west side of Los Angeles, and they have annual gala events and fundraisers. The parents donate something like two weeks in a Swiss chalet or whatever, and I’m the cheapskate, so I say, “Drum lesson by Stewart Copeland.” At some point, a dad brings his kid over and the kid could care less, but the dad’s fanboying about the Police. Basically, I tell the dads stories and show the kids how to hold the sticks. But one year, a dad comes over with no kid. He wants a drum lesson. It’s a pretty expensive school. He must have achieved something in life. I show him a few things on the drums. I’m gently trying to find out, “Are you a musician? You play in a band?” But he sees my Spyro frame, which says triple platinum. He says, “Oh, Spyro. Do you enjoy those games?” I said, “Yeah. I’m actually thinking of taking Spyro and orchestrating it and turning it into an orchestral piece. I just have to find the guy who now owns the copyright.” And he responded, “I can help you with that. I own them. I’m the CEO of Activision. Now that you mention it, we ought to reissue that game.” So two years later, they reissued it. They rebuilt it from the ground up.

Most ambitious thing the Police have left to do

We have no intention of doing anything.

More From The Superlative Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music