This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Bruce Willis’s stardom began in a boardroom at ABC in 1984. The network’s top executives had gathered to discuss Moonlighting creator Glenn Gordon Caron’s desire to cast the lead male role of David Addison with Willis, an ex-bartender from New Jersey whose only notable credit was a guest spot on Miami Vice. The executives pushed for a famous name to pair with Cybill Shepherd, a model turned actress who’d been a familiar face since the late 1960s, until the lone female executive in the room announced that she preferred Willis because he looked like “one dangerous fuck.”

Willis got the part and brought a live-wire energy to Addison. The character was a Dagwood sandwich of contradictions. He was a self-proclaimed sexist who happily worked for a female boss and could be empathetic and chivalrous. He was a Jersey guy (like Willis) who had a common touch but could do Marx Brothers–level wordplay; drop references to classical music, theater, poetry, and mythology; and launch into a cappella renditions of ’60s soul classics. When he wasn’t working a case, he lived inside his art-and-culture-and-pop-music-saturated brain. With his sandpapery tenor voice, sinewy body, slightly receding hairline, bad-boy smirk, and soulful eyes, Willis was believable as a man whose joker act was self-protective. He was a romantic at heart, capable of intense, even doomed longing — a quality that was teased out in various self-enclosed episodic story lines before the writers finally got David and Maddie (Shepherd) together in season three, destroying the “will they or won’t they” tension that had made the show a hit.

After going from anonymity to TV superstardom in a matter of months, Willis immediately began laying track for a movie career. He started in the late ’80s with two Blake Edwards pictures, Blind Date and Sunset, and over the years, he would continue to milk the hyperverbal wiseass persona, including as the title character of the Rat Pack–influenced Hudson Hawk, the alcoholic tabloid journalist Peter Fallow in the disastrous Brian De Palma adaptation of The Bonfire of the Vanities, and the ex-mobster turned suburbanite Jimmy Tudeski in The Whole Nine Yards and its sequel. It’s easy to envision an alternate timeline in which Willis avoided macho action-hero roles and instead became something akin to a blue-collar Cary Grant: a cagey, self-aware, silver-tongued charmer who rarely punched anybody because he was so good at talking himself out of tight spots.

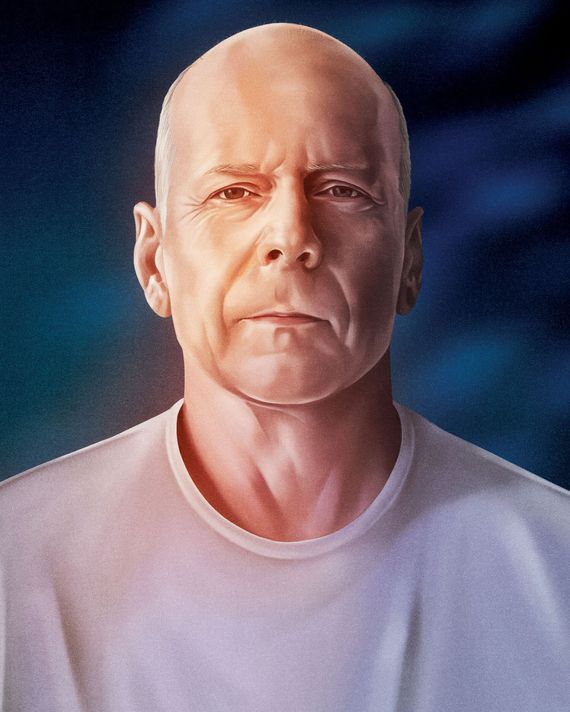

But by the time Willis retired from acting in March owing to aphasia, a brain disorder that affects speech and cognition, he was best known for playing exceptionally violent men of few words in the tradition of Clint Eastwood, Charles Bronson, and the two ’80s action superstars to which his early persona had offered an alternative: Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. His transformation was among the most drastic in pop-culture history. By 1998, Michael Bay’s science-fiction actioner Armageddon was casting Willis as a cynical, surly, know-it-all oil driller loosely modeled on real-life oil-well firefighter Red Adair, previously fictionalized in the John Wayne epic Hellfighters. David Addison was being scrubbed away a bit more each year. In his place was a vision of American manhood that would have been at home in the 1950s.

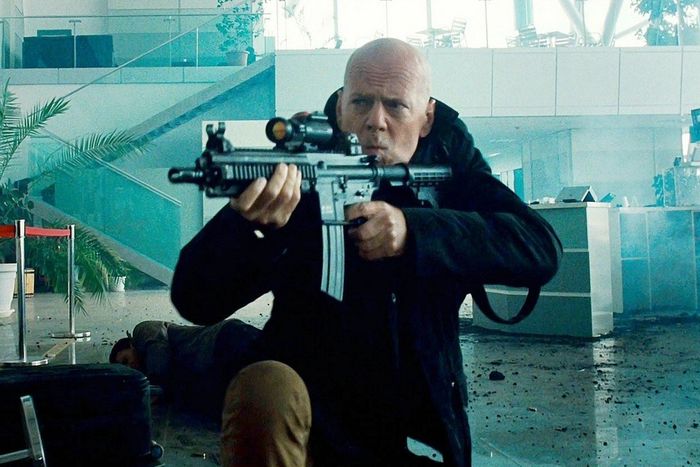

In recent years, the tight-lipped, supermacho incarnation of Willis was increasingly showcased in direct-to-video quickies that paid him by the day for what amounted to glorified cameos. On the set of those productions, he couldn’t remember lines and seemed confused as to where he was. Rather than accept the reality of the actor’s obvious incapacity, members of Willis’s professional team — producer Randall Emmett, his producing partner Stephen J. Eads, and actor Adam Huel Potter — chose instead to reduce his screen time, cut as many of his lines as possible, and have the remainder fed to him through an earpiece or read aloud off-camera so he could repeat them. (His lawyer, Martin Singer, told the Los Angeles Times, “My client continued working after his medical diagnosis because he wanted to work and was able to do so, just like many others diagnosed with aphasia who are capable of continuing to work.”)

That Willis’s evolution from a smooth-talking romantic alpha to an uncommunicative meathead made the alleged exploitation easier to hide is a sad irony of his late-career decline. In some ways, his man-of-few-words mode — which he stayed in for most of his career — made it difficult for audiences to see that he wasn’t fully there anymore.

Six years before Die Hard’s John McClane ran barefoot over broken glass at Nakatomi Plaza, Stallone had punished himself for the audience’s delectation in First Blood, kicking off the craze for one-man-army thrillers. Rambo was Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle by way of Frankenstein’s monster: a killing machine created by the U.S. government and left to fend for himself against sadistic cops who tormented him until he snapped, leading the National Guard on a manhunt, diving off a cliff, sewing shut his own gaping arm wound without anesthesia, and setting a town on fire. Watching the film again with 40 years’ hindsight, you can see ’70s-cliché masculinity ebbing and the ’80s version supplanting it: less body hair; more muscles; sneering disdain for unmanly men and anyone insisting that things be done in a proper, established way; fewer conversations with, or about, women.

It was presumed that these kinds of projects needed a certain type of lead: usually, a skull-cracking, throat-slitting he-man who looked as if he spent four hours a day at the gym, ridiculed anyone who expected the hero to play by the book, and delivered knowingly corny kiss-off lines before and after killing. The format was so popular that actors who didn’t necessarily fit the profile adopted it. Eastwood, by then well into his 50s and a pioneer of this type of picture, added so much muscle mass for Heartbreak Ridge, City Heat, The Rookie, and two more Dirty Harry movies that he started to appear on fitness-magazine covers like his younger rivals. In 1989’s Black Rain, Michael Douglas, who had become a movie star playing yuppie sleazeballs, starred as a Stallone-style New York cop who escorts an arrested yakuza member to Japan, insults pretty much everyone he meets, defies protocols and rules, and is ultimately given a commendation for heroism and hailed as a man who has much to teach the Japanese.

In 1987, another of these movies, Die Hard, was pitched to studio executives as Rambo in an Office Building. The project was believed to have such inherent commercial potential based on the concept alone that the producers and the releasing studio, 20th Century Fox, decided to start production without casting the lead. They offered McClane to Stallone, Schwarzenegger, and Mel Gibson; all declined. Kurt Russell, Burt Reynolds, Eastwood, and Harrison Ford were reportedly considered. The eventual choice of Willis — hired for a then-unheard-of $5 million to lock in a name, any name — was controversial and in some quarters laughable. The public knew him only as a fast-talking romantic-comedy lead, a pitchman for Seagram’s wine coolers, and a would-be R&B star stage-named Bruno. The film, which premiered ahead of Moonlighting’s final season, vaulted him out of television and spelled that show’s doom.

Willis turned out to be perfect for a variety of reasons, including his human-scale machismo (a marked contrast to the swole invincibility of Stallone and Schwarzenegger) and his credibility as a quick-thinking problem solver. The filmmakers positioned McClane as a blue-collar, Reagan-era American answer to James Bond who pines for his estranged wife, Holly (Bonnie Bedelia), and forges alliances with other working stiffs as he profanely tells off bureaucrats, smug functionaries, and even the film’s villain, a sneering German terrorist who quotes Alexander the Great and buys his suits at John Phillips of London. Director John McTiernan kept the Rambo-esque posing and pouting to a minimum. From the rotator-cuff-surgery scar (actually

Willis’s) showcased with tank tops to the way McClane cries on the phone with his new friend, the LAPD sergeant Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson), while asking him to tell Holly she was “the best thing that ever happened to a bum like me,” McClane is a man, not a superman. Cocky as he could be, Willis kept foregrounding the character’s vulnerability, flouting ’80s action-cinema norms. Willis’s McClane was as innovative a male lead as John Cusack’s kickboxing philosopher Lloyd Dobler in Say Anything the following year.

Over time, though, Willis started moving away from the thoughtful Everyman action hero he had incarnated in Die Hard and toward more retrograde macho-man roles. The Die Hard sequels were far more typical of the era’s R-rated action blockbusters, stressing McClane’s sour cynicism and lethal skills instead of his humanity. It was hard to tell if Willis was trying to put Moonlighting even further in the rearview mirror, if the stone-faced-killer parts spoke to some need in him as an actor, or if he was just doing the thing he knew audiences would pay to see.

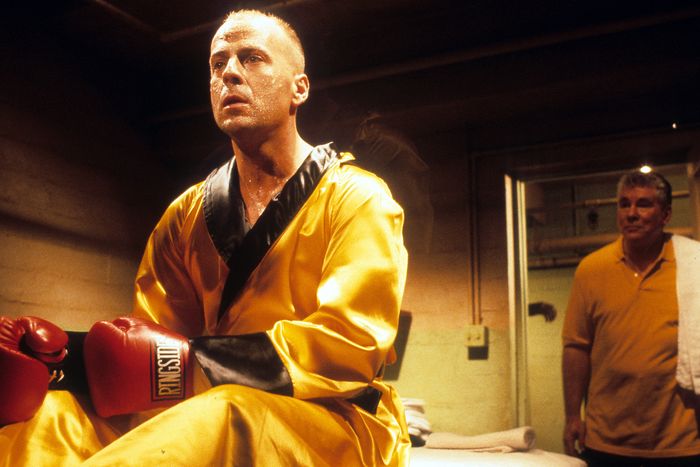

Two roads diverged with Pulp Fiction. It was one of the biggest and most unexpected hits of ’90s cinema — and as influential on crime films as Die Hard had been on action ones. Like all Quentin Tarantino pictures, it was anchored by grandiose, logorrheic narcissists who express themselves in banter and monologues. The Moonlighting Willis could have aced that sort of part (it’s easy to picture him as philosophical hit man Vincent Vega), but Tarantino chose to cast him against type with striking results. Butch Coolidge is the most quietly intense of Pulp Fiction’s major characters. He can be talkative, sweet, and vulnerable when he’s with his French girlfriend, Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros), or panicking over the whereabouts of his father’s gold watch. But in every other scene, he’s a nearly silent man of action, loping around Los Angeles and neutralizing adversaries with a samurai sword and an Uzi. The next year brought Terry Gilliam’s time-travel fantasy 12 Monkeys, which let Willis continue in a strong-silent vein. His character, James Cole, casually dispatches foes with his fists and any weapons he can get his hands on, but he’s also sensitive, haunted, and childlike. In the high point of the performance, listening to Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill,” Willis shouts, “I love the music of the 20th century!” and sticks his head out of the window of a moving car, laughing with joy.

With the one-two punch of Pulp Fiction and 12 Monkeys, the bifurcation of Willis’s screen persona became pronounced. Over the next decade, he would alternate men who love to talk with men who barely speak. M. Night Shyamalan gave him two more quiet types. In 1998’s The Sixth Sense, Willis played Dr. Malcolm Crowe, a psychiatrist counseling a boy named Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment), who can see dead people. Crowe is a great listener who asks a lot of questions, but when you think back on the movie, what you remember is Willis’s stillness. Some of the most memorable scenes, as in Pulp Fiction, rest on close-ups of him thinking. The Sixth Sense became one of the top-grossing films of all time and, like Die Hard and Pulp Fiction before it, ushered in a wave of similar horror films whose impact hinged on twists that reoriented the viewer’s perception of what the story was about. “Clearly, Mr. Willis isn’t interested in just squandering his currency in action, preferring to shift his attention outside his normal purview,” wrote then–New York Times film critic Elvis Mitchell. “Such an instinct shows Mr. Willis’s compulsion for making the odd bets — and often as not, he rolls a winner.” He rolled another in Shyamalan’s 2000 follow-up, the grimdark comic-book riff Unbreakable, playing the morose, borderline-mute security guard David Dunn, who survives a train crash and eventually realizes that it’s because he’s a superhero. (He would reprise the role in two more films, Split and Glass.)

By the late ’90s, Willis had established himself as a versatile lead who could switch between cranky bruisers and sensitive souls, but the killers and tough guys were what kept him at the top of the A-list. He played rough and mean in Walter Hill’s Yojimbo remake, Last Man Standing; Mercury Rising; The Jackal (as a rare villain); and Armageddon, as Harry S. Stamper. You could say Willis’s career was never the same after Pulp Fiction — you could also say it never recovered. He had built a gilded cage for himself, and it was hard to get out. His off-brand, often indie-film performances indicated he didn’t want to be defined solely by glowerers and killers any more than he had wanted to be confined to playing wiseasses back in the Moonlighting days. But whenever he played “character” roles, as in Breakfast of Champions, The Siege, Hart’s War, Alpha Dog, Fast Food Nation, and The Astronaut Farmer, he didn’t pop, as the filmmakers clearly wanted him to. Willis was too subtle to just rumble into a scene and mulch it — an approach his more acclaimed peers (from Jack Nicholson and Robert Duvall to Billy Bob Thornton and John Malkovich) were willing and able to take. For all the manic charisma Willis displayed early in his career, he was unwilling (or unable) to go big in the manner of a movie star hamming it up. He was nuanced in the best and worst way.

His career as a leading man fell off in the mid-aughts, coinciding with his drift into undemanding tough-guy parts. There were occasional roles that blended early and late Willis — the cocky, loquacious charmer and the stone-cold killer — notably, retired assassin Frank Moses in the 2010s action-comedies Red and Red 2. But as time wore on, audiences saw him playing more of the lethal burnouts and generic cop-military-mercenary types, losing any vestige of his other screen selves. Even Rian Johnson’s Looper and Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom cast Willis in roles that were essentially sad-sack, character-actor versions of his macho-hero parts in ’90s action flicks. Nobody thought to play on his other past incarnations anymore (or if they did, he didn’t say yes).

Willis embraced his own caricature by appearing in two of Stallone’s three Expendables tentpoles, which were the action-adventure equivalent of those old K-tel record-and-tape sets: every star who has ever done an action movie in one collection. Arnold Schwarzenegger! Jean-Claude Van Damme! Wesley Snipes! Jason Statham! Chuck Norris! Jet Li! Dolph Lundgren! While the films gave tasty morsels to bit players, they were cash machines for aging idols.

The third, and regrettably final, phase of Willis’s acting career consisted almost entirely of tight-lipped assassins, gangsters, soldiers, and uniformed authority figures in a whopping 32 direct-to-video films (three are as yet unreleased). They’re soul-crushingly meh and Willis is barely in most of them, even though the marketing departments ensured that his name and face were as big as possible on the streaming-menu poster thumbnails to make it seem as if they were Bruce Willis films as opposed to ones that happened to contain trace elements of Bruce Willis.

What a shame it all was. He was the kind of star who might have enjoyed a late-career renaissance after settling into vanity-free character roles. He was already deep into the period of actors’ lives when they can barely walk into a room without being handed an award. It wasn’t hard to imagine Willis being given a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in his 70s or 80s or scoring a Supporting Actor nomination in regular competition — maybe for playing an over-the-hill alpha male, like former action stars Reynolds (Boogie Nights) and Stallone (Creed) before him.

He had the stuff. But he lost it. And we may never know how or when it happened — or which part of the loss was the cumulative result of Willis’s own choices and which was due to the actions of advisers who didn’t have his best interests at heart. Did Willis’s artistic standards sink and then he began to decline cognitively? Or did the decline start long ago, out of public sight, prompting him (or his handlers) to start saying yes only to material that was undemanding enough for an impaired actor to handle? If he had tried to play another role like David Addison, or Jimmy Tudeski in The Whole Nine Yards, or even Peter Fallow in Bonfire of the Vanities, the news might have gotten out sooner that he was in ill health and perhaps a victim of exploitation.

How many authors did this tragedy have? There will be more stories about it and possibly some kind of legal action. But the most important account, Willis’s, won’t be reliable because of his condition. And because of that condition, it’s unlikely he’ll ever have a real-life moment like the ones his heroes often have in the movies, in which they put all the pieces together or come to a cathartic understanding of their predicament, like Dr. Malcolm Crowe in The Sixth Sense seeing his wedding ring roll across the floor.