You probably remember it. But if you don’t, it goes like this. A little boy receives a stuffed rabbit for Christmas. From a wise old toy, the rabbit learns that when a child loves you for a long time, you become Real, and the rabbit yearns to be Real himself. Eventually, he gets his wish: The boy plays with him all spring and summer, and the rabbit doesn’t mind that his coat has grown shabby and his stuffing is coming out, because he knows he is Real to the boy. But when the boy gets sick with scarlet fever, the doctor orders the rabbit to be burned alongside the other germ-ridden playthings. Shivering on the trash heap, the little rabbit wonders what it all was for. He cries a tear — a real tear — and from the fallen tear there grows a flower, and out of the flower steps a beautiful fairy, and the fairy transforms him into a real rabbit at last.

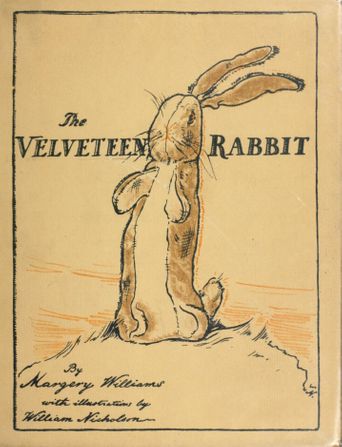

This is the plot of that beloved classic of children’s literature The Velveteen Rabbit. First published in book form in 1922 by a little-known novelist named Margery Williams Bianco, it has now been in print for a century, selling over a million copies in the U.S. alone. Dozens of illustrators have reimagined it, including Maurice Sendak three years before Where the Wild Things Are. It is frequently adapted for the stage, and Meryl Streep received a Grammy nomination in 1986 for a recording of it she made with the pianist George Winston. This year, Doubleday released a 100th-anniversary edition with stunning new art by award-winning illustrator Erin Stead. All the while, it has remained a humble bedtime story across the English-speaking world. Perhaps you read it when you were small; perhaps you have read it to someone smaller.

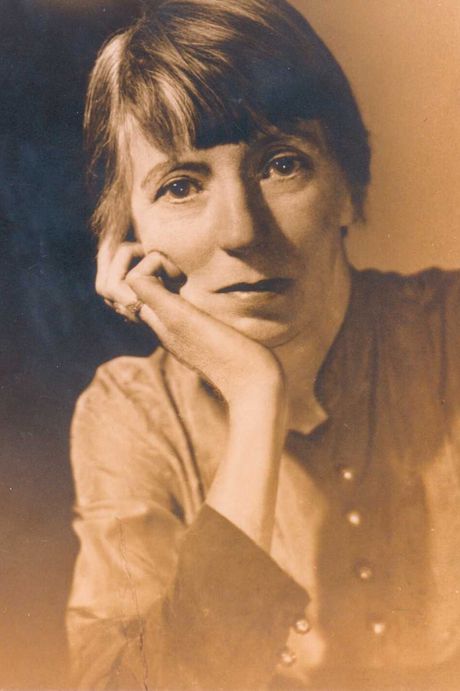

Yet The Velveteen Rabbit was always more than a children’s book. Bianco, already the author of five unsuccessful novels for adults, had once longed to be a writer of serious fiction, but by the time she wrote The Velveteen Rabbit, she had not published a book in eight years. Two decades later, and by then a widely respected author, translator, and critic of children’s books, Bianco would scorn attempts to draw a line around writing for young people, preferring to refer more expansively to what she called “imaginative literature” intended for all ages. “If you do not respond to its magic, you have either traveled many leagues from its enchanted land, or will never qualify to enter it,” she wrote of such literature. “Reality and unreality interpenetrate, but this is confusing only to those who feel that unreality — or that which takes place in the imagination — should be kept always in a properly labeled compartment.”

The philosophical character of The Velveteen Rabbit, whose subtitle is How Toys Become Real, reflected Bianco’s abiding interest in the relationship between reality and the imagination. “The child mind is far more logical and orderly, far more concerned with the value of realities, than is sometimes supposed,” she wrote. “The fact that these realities may differ from our own has no bearing on the question.” Children are perfectly well aware that the lives of their beloved playthings are imaginary; what they lack, Bianco believed, are the barriers that will be erected in adolescence between imagined realities and material ones. After all, it is quite easy to prove that the imagination makes things real: We call this reading. The little boy’s love for his treasured rabbit is not so different from an adult’s absorption in a good book. For Bianco, the necessary role of fiction was to act as a mental preserve for the once-wild faculty of the imagination, whose domestication is a bittersweet but essential condition of adulthood.

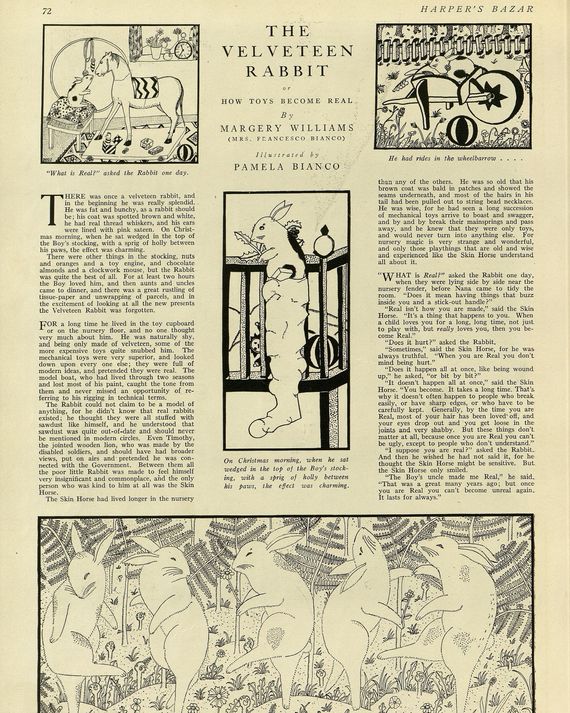

This was not an abstract subject for the author. Her daughter, Pamela, a child prodigy, had quickly gone from playing with dolls, including Bianco’s own old stuffed rabbit, to her first gallery exhibition at the age of 12, attracting the attention of art collectors and an enchanted press. In fact, the first published version of The Velveteen Rabbit, commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar in 1921, served as a vehicle for original illustrations by Pamela, whom the magazine had effusively profiled in an earlier issue. (The story’s author was advertised as “Pamela’s mother.”) It isn’t hard to read The Velveteen Rabbit as an elegy for a daughter who grew up too fast. Indeed, as in all imaginative literature — all fiction, perhaps — the story represents at once the persistence of childhood and a memorial to its loss.

Bianco was born in London in the summer of 1881, the daughter of a barrister who was also a distinguished classicist. “To be the youngest of a family by as much as six years is almost like being an only child,” she recalled. She learned to make do with her imagination, inventing stories with her stuffed rabbit, Fluffy, and tracing paper animals out of the green three-volume set of J. G. Wood’s Illustrated Natural History that belonged to her father. She began keeping pet mice in her dollhouse, and she liked to steal plant cuttings from the park when the gardeners weren’t looking. Bianco’s father died when she was 7; soon thereafter, the family immigrated to a farm outside Philadelphia, where the young girl began writing adventure stories set in the Amazon or Wild West, editing her manuscripts from the solitude of the staircase landing.

By the dawn of the 20th century, a youthful Bianco had returned to London with dreams of becoming a professional writer and “a grand collection of rejection slips.” Her first novel, published in 1902, about a failed insurrection in a nameless tropical republic, is impressionistic to the point of being unintelligible. Later novels — derivative romances in a more realist mode — feature witty female protagonists sharpened to a stylish edge: a bitter atheist with a dark secret, the restless bastard daughter of a drowned sailor. To make ends meet, Bianco found employment with a London publisher of Christmas stories, where she tossed off copy for treacly illustrations of “nice fat little girls or puppies or dolls.” She so despised the job that she stuck her feelings into a short story in which an alcoholic newspaperman ends up writing “simple little tales with an obvious moral tacked on” for a Sunday-school press. Decades later, Bianco would carry this hatred of mawkishness into her career as a children’s author, lambasting what she saw as “that form of weak pseudo-realistic writing, too often mistaken for realism, which deliberately falsifies life, through sentimentality, through the desire to portray a world in which everything is easy and simple, all difficulties melt at a touch and reward hangs like a ripe apple for the gathering.”

After her fourth disappointing book, Bianco stepped back from writing in favor of her newly cosmopolitan family life. In 1904, she had married a suave Italian bookseller named Francesco Bianco — she pronounced his name, which she took, bee-YANK-oh — and she now had two small children: Cecco, named for his father, and little Pamela, to whom Bianco entrusted her old toy rabbit, Fluffy. In 1907, the Biancos moved to Paris, where they befriended the American writer Gertrude Stein, whose salons had just begun to attract the Parisian avant-garde. After a few years back in England, the family relocated to Francesco’s native Turin. In Italy, Bianco would take the children to see the Italian masters at the local pinacoteca, where Pamela fell in love with Botticelli’s angels, and the family began holding little writing contests to be judged by Francesco, who was often away on business. (On one such trip, Bianco recalled, her husband mailed home “a sort of open pie called pizza” that rotted in the post office before anyone thought to retrieve it.)

Bianco published little during this time, owing in no small part to the demands of motherhood. In Paris, she had taken to writing with her manuscript book in her lap so she could oblige her children at the drop of a hat, drawing pictures for Pamela or folding paper toys. In retrospect, her most notable work from this period is “Eugene,” a short story published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine in 1912. The story reads like a dark distortion of the sickly sweet Christmas stories she had contemptuously churned out as a young copywriter. Six-year-old Eugene is rude, ill tempered, and ignored by his mother; when he tries to join the neighbor girl for Christmas dinner, the girl publicly humiliates him. “Eugene” was clearly written for adults — its eponymous ankle biter calls a Black waiter a racial slur — but the story’s themes of loneliness and neglect would reemerge a decade later in Bianco’s books for children.

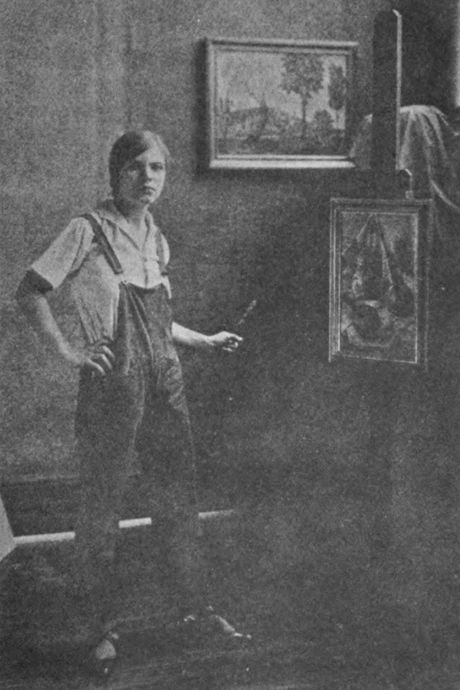

First, recognition would find a different Bianco. During the Great War, Pamela began to demonstrate a talent for art. Every day, she produced strange, dreamlike line drawings of little girls holding pomegranates, winged Madonnas covered in flowers, rabbits dancing in the forest. When Francesco submitted her pictures to a children’s art exhibition, the committee couldn’t believe they were the work of an 11-year-old girl. Pamela had her first solo show at a London gallery in 1919, and word spread of a child prodigy. The Italian poet and protofascist war hero Gabriele D’Annunzio reportedly called Pamela “a marvelous child with a name resembling a new flower.” The symbolist poet Walter de la Mare, then well known to the British public, wrote verses to accompany Pamela’s illustrations for a book-length collaboration called Flora. A second London exhibition drew the attention of the American art collector Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, later to found the Whitney Museum of American Art, who declared that her “countrymen must see the work of the world’s child marvel.” By 1921, led by Pamela’s growing fame — largely the work of the garrulous Francesco, her self-appointed manager — the Biancos had all moved to New York City. The little girl herself, swiftly thrust into premature adulthood, opted to leave her stuffed rabbit in Italy.

Bianco, now almost 40 and eclipsed by her own daughter, weighed a return to writing. “I disliked everything I had written before,” she recalled. “I wanted to do something different but did not know what it should be.” She was tired of the modish modernism she had aped in her youth. “Whenever I find myself breaking out into words — that sort of writer’s measles which is so detestable — [I] always know it’s because I hadn’t something to say,” she would observe many years later, noting how the recursive abstraction of her old friend Stein had always reminded her of a “gramophone needle that gets stuck and keeps tugging on the same phrase.” Searching for a more direct literary style, Bianco began to think back on the stories she had imagined for her young children, which were characterized by a charming matter-of-factness. (“The Tubbies are very well and happy,” she had once written to a young Pamela, informing her that her dolls were invited to a picnic with dancing to follow.)

Meanwhile, Pamela’s solo exhibition at the Anderson Galleries on Park Avenue at 59th Street had been a smash hit. The New York Times praised the girl’s “tiny sketches of rabbits,” and the show’s many buyers included the songwriter Jerome Kern and the art collector Helen Frick. A writer for Harper’s Bazaar described the exhibit in particularly florid terms: “A bacchanalia of ecstatic rabbits lead me on fluffy, Terpsichorean paws into her enchanted woods, where fairies and babies, and birds and flowers, and angels and madonnas, in a divine tangle of bliss, worship spring.” To the press, Francesco sought to portray his daughter as a natural talent who just happened to be an heir to the Italian Renaissance. “We never talk art in the family,” he boasted to the New York Tribune while Pamela sat quietly next to him petting a family cat. The little artist demonstrated only a passing interest in her remarkable success; her chief concern during the show had been to ensure that a portrait of her beloved late guinea pig, Tiddles, be clearly marked NOT TO BE SOLD.

However Bianco felt about all the panegyric — motherly pride, professional envy, guilt — a chance opportunity would soon hitch the failed novelist to her daughter’s rising star. Eager to capitalize on a faddish child prodigy, Harper’s Bazaar commissioned Bianco to write a story for Pamela to illustrate. Bianco would later describe it as “a sort of accident” that “became the beginning of all the stories written since.” In June 1921, the magazine ran a four-page story called “The Velveteen Rabbit, Or How Toys Become Real,” the simple, thoughtful tale of a shy stuffed rabbit whom a fairy transforms into a real rabbit after he is lost by the little boy who loved him. The magazine billed it as a “fairy story for grown-ups,” but its true audience was arguably Pamela herself, whose forgotten stuffed rabbit had since transmigrated into the young artist’s numinous drawings, where it could often be seen holding between its tiny paws a flower like the one from which the fairy emerges in the story. Pamela was becoming real too, and Bianco had captured not only the joy and grief of transformation but also the imaginary world that was dying off with her daughter’s abbreviated childhood.

In 1922, The Velveteen Rabbit was published as a book just in time for Christmas shopping. The first edition, dedicated to Francesco, featured haunting lithographs by the acclaimed British printmaker William Nicholson. Anne Carroll Moore, the imperious children’s librarian at the New York Public Library, declared the book a classic in the Hans Christian Andersen tradition that was “destined to live in the remembrance of every child and grown up” who reads it. A tastemaker best remembered today for despising Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, Moore would champion Bianco’s work throughout what would be the latter’s long career as a children’s author. (Bianco herself would call Moore the Velveteen Rabbit’s “godmother.”)

By 1929, Bianco had published seven more books for children and translated two others from French. She took this work as seriously as she had ever taken writing for adults — perhaps more so. In her 1925 essay “Our Youngest Critics,” Bianco described child readers as “an audience at once eager to be amused yet highly skeptical of the deliberate attempt to amuse; uncertain of what it does want but amazingly definite as to what it does not … appreciative of results when they come out right but wholly devoid of that weakness which makes us bear with an artist through sympathy.” These standards had given Bianco perhaps the first experience of deep professional satisfaction in her life, forcing her to discard “the skilful embroiderings and unessentials, the nice picking of phrases and building up of ‘atmosphere’” that characterize her early novels. “To these critics,” she wrote, as if relieved, “style means very little.” What mattered most was simply that the writer win the reader’s confidence. “The one essential thing the writer must have, to succeed at all, is a real and genuine conviction about his subject,” Bianco concluded. “It has got to be real to him.”

In her description of the task of the children’s author, one can hear an echo of the shabby little protagonist who had launched her career. “What is REAL?” the Velveteen Rabbit asks the Skin Horse, the oldest and wisest toy in the nursery. The rabbit has heard the mechanical toys bragging about their moving parts and scale-model details. “They were full of modern ideas,” Bianco wrote, “and pretended they were real.” This worries the rabbit, who has let himself be convinced that his sawdust filling is cheap and unfashionable and doesn’t even know that his velveteen is, in fact, imitation velvet. But the Skin Horse — not an invention of Bianco’s but a popular 19th-century pull-along toy consisting of calfskin stretched over a wheeled frame — kindly reassures him. “Real isn’t how you are made,” says the old horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.” The Skin Horse’s proverb, which remains perhaps the most quoted line of The Velveteen Rabbit today, articulates an idea Bianco would return to again and again in both her fiction and her criticism: namely, that the metaphysical status conferred by the imagination is not only real but far realer — and not in a metaphorical sense — than any product of literary craft or intellectual abstraction.

But this kind of Real cannot last forever, despite what the Skin Horse says. Bianco would acknowledge that those same curious “extensions of reality” that the child mind accepts without question will “by the later light of acquired reasoning” appear strange and unbelievable to the adult. As the child grows, the internal logic holding the imagination together — along with the realities contained therein — begins to break down; the adult mind, in the interest of its own integrity, will be “contented to class as dream” what it once knew to be real. “But who can say where dream ends and reality begins?” Bianco mused.

The rabbit asks himself this question when he is confronted with two wild rabbits in the garden who twist and contract as they leap into the air. “He isn’t a rabbit at all! He isn’t real!” one of them shouts after examining the worn little toy before the pair slip away into the bracken. The wild rabbits pose a possibility that the Velveteen Rabbit, who until this point has believed that all rabbits are stuffed like himself, has never even considered: a new, more mature concept of reality, elusive and inherently changeable, continually withdrawing from the imagination’s tidy reach into a dark and unintelligible material world.

There is, in other words, a second Real. This was Bianco’s greatest insight, the one that made The Velveteen Rabbit a genuinely philosophical work — that the true task of growing up lies not in simple self-actualization but in carefully negotiating the delicate transition from one order of reality to another. Central to this transition is the limiting of the imagination to more indirect spheres of experience (dreams, literature, art) in exchange for an independent, more plastic sense of self. But the process, by necessity, will begin with tragedy. Just as the Velveteen Rabbit comes to believe he will be Real forever, he is thrown out. “Of what use was it to be loved and lose one’s beauty and become Real if it all ended like this?” the heartbroken rabbit wonders. A tear drops from his eye and out steps the beautiful fairy who promises to make him Real. “Wasn’t I Real before?” the little rabbit asks. “You were Real to the Boy,” the fairy gently replies, “because he loved you. Now you shall be Real to every one.”

In real life, of course, there are no fairies, and Bianco had a lifelong abhorrence of the coddling of children. “The mission of fantasy, far from belying truth,” she wrote, “is often to present truth in an understandable form.” The fairy may be an obvious narrative device deployed to soften the unfortunate end to which every well-loved plaything comes, but she does not make the rabbit Real the way the boy once did. She is not a powerful Other but a slantwise aspect of himself that emerges from his own very real tears, which already contain all the magic required to effect his final transformation into a real rabbit. He has learned, in the words of one of Bianco’s early novels, “the eternal paradox that only with love comes the strength to do without love.” The remedy for his loneliness will no longer derive from someone else’s imagination but from himself, in all his wildness and mystery. In other words, the Velveteen Rabbit does the one thing no work of imaginative literature, not even The Velveteen Rabbit itself, can ever do: He steps out of the mind and into the real world.

Pamela would do the same but with even greater difficulty. In 1926, at the age of 19, she suffered a nervous breakdown ostensibly brought on by a bad case of measles. Bianco called her daughter’s psychotic break a “catastrophic” time for the family, describing Pamela as a “leopard in the jungle, tearing up her bedlinen nightly.” During the episode, Pamela hurled glasses of water across the room and talked incessantly, forcing a friend to listen to the life history of the Buddha; she tore up pillowcases to make book jackets and screamed at visions of floating powder boxes. “I have no interest in life and I’m about sick of everything most of the time,” Pamela wrote to a friend. “Continually, my mind goes back to my early childhood in Italy, and I worry amazingly over all sorts of little things that happened then.” The Biancos sent her to see a nerve specialist. “Today I went out for the very first time in a taxi,” Pamela wrote. “It seemed like a dream all the time — nothing was real.”

Childhood fame evidently exacted its familiar toll on the young artist, who had spent years cannibalizing the imaginary world of her own youth for the consumption of adults all too eager to praise her childlike innocence; it might have taken many more for her to recover her sense of reality. In 1930, Pamela returned to her beloved Turin on a Guggenheim Fellowship to study painting. “Years of illness may disappear when I reach Italy,” she wrote hopefully. Her late-1950s painting Pomegranate, a glittering, geometric rendering of the fruit she liked to draw as a child, is held in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Bianco, for her part, would publish over 30 books in her lifetime, the vast majority of them for children. As a frustrated novelist, she had learned the hard way that every work of fiction represents an attempt by the imagination to grasp its own finitude, and eventually she dedicated her career to helping children make peace with their own endings. She would even write a sequel to The Velveteen Rabbit called The Skin Horse, in which the ruined old horse, resurrected on Christmas Eve as a brilliant Pegasus, flies a terminally ill boy off into the dark night. “You don’t have to educate children about death,” Bianco wrote two years before her own death in 1944. “Speak of it as a natural occurrence and they will do the same.” A real rabbit, after all, is one that has been given the gift of mortality. In “Our Youngest Critics,” Bianco acknowledged that some of the greatest works of children’s literature have dealt in “the sadness which is inseparable from life, which has to do with growth and change and impermanence, and with the very essence of beauty.” But even this, she supposed, was too grown-up a way of thinking. “It is quite possible that to the child, so far as he is aware of them, those things may not be sad at all: they may be quite natural and inevitable, and just as they should be,” Bianco wrote. “Perhaps his way of looking at them, and not ours, is the right one.”