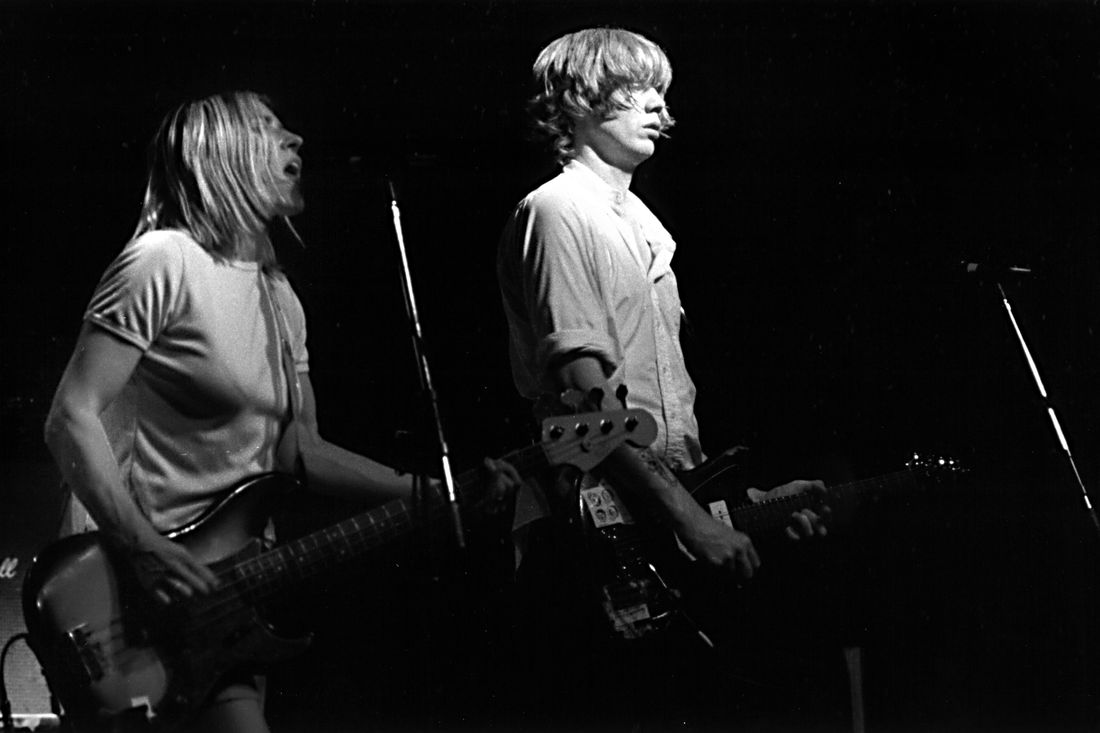

By time of their breakup in 2011, Sonic Youth had released essential studio albums during four U.S. presidencies (and a pretty good one, 2009ÔÇÖs The Eternal, during a fifth), erected an unlikely bridge between the noisy underground and mainstream alternative radio, and barreled through every permutation of guitar music with KISS on one end of the spectrum and Lou ReedÔÇÖs Metal Machine Music on the other. The band appeared to be a true creative democracy of like-minded experimentalists dedicated to expanding the parameters of how a rock song could sound, and contained within it a seemingly ideal artist relationship with the marriage of Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon, who evolved from starving bohemians to magazine-friendly style icons to┬ásuburban parents, yet never appeared anything less than the template of studied cool. Or, as Moore writes in his new memoir, Sonic Life, about watching his idol, Patti Smith, perform with her husband, Fred ÔÇ£SonicÔÇØ Smith (whose nickname would inform MooreÔÇÖs own band), as a young man: ÔÇ£It was an emblematic vision of all I would ever desire from rock and roll ÔÇö transcendence, devotion, sonic love.ÔÇØ

For three decades, he appeared to fulfill that vision. So when Moore left his wife for someone else, it threatened to affect how the band would be remembered. How could it not? Sure, adultery is one of rock and rollÔÇÖs many prurient flavors alongside cocaine abuse and devil worship; Fleetwood Mac didnÔÇÖt sell over 40 million copies of Rumours by honoring the Ten Commandments. But MooreÔÇÖs affair became public as online discourse and was being remapped by progressive-leaning social-media platforms and as the music industryÔÇÖs sexist norms were being reappraised ÔÇö which, for many fans, made his cheating seem like a personal slight, not the private business of two adults.

Gordon was the first to provide a gory detailing in her 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, where she emphasized the clich├®d origins of their marital break: stagnant partnership, secret rendezvous, the other woman. ÔÇ£The drug that was her had turned him into a serial liar, to the point where two of our very good friends had recently told me they were so put off by what one called ThurstonÔÇÖs ÔÇÿdarknessÔÇÖ that they didnÔÇÖt want to come by our house anymore,ÔÇØ she wrote, as their attempts to reconcile were failing. If the righteousness of her anger didnÔÇÖt wipe away Sonic YouthÔÇÖs accomplishments, it made Moore seem boorish and unthoughtful ÔÇö a little boy lacking self-knowledge, not a guitar god. IÔÇÖve never read a better puncturing of rock-and-roll posturing than the opening pages of her book, which describe her revulsion at MooreÔÇÖs showy camaraderie during Sonic YouthÔÇÖs final show.

The gossip-curious hoping Sonic Love is a tell-all dishing how and why Moore could dynamite the Royal Couple of art rock will leave unfulfilled. ÔÇ£The circumstances that led me to a place where I would even consider such an extreme and difficult decision ÔÇö to leave my marriage to Kim, my partner and bandmate of almost thirty years, the mother of our child, the adored aunt to my nieces and nephews ÔÇö are intensely personal, and I would never capitalize on them publicly, here or anywhere else,ÔÇØ he writes as his nearly 500-page book approaches the final days of Sonic Youth ÔÇö and with it his marriage. This bit of well-considered legalese is about as far as he goes regarding this particular subject. (Also, sheÔÇÖs not thanked in the acknowledgments, nor are the other members of the band, guitarist Lee Ranaldo and drummer Steve Shelley.) Which is too bad because their marriage was such a fundamental part of the band, not only in the way it informed the music they made but in how it appeared to center and structure a worthwhile creative life, one worth emulating right up until the point where it visibly wasnÔÇÖt.

Sonic Life is mostly written like a coming-of-age story of MooreÔÇÖs time in 1980s downtown New York City, where he fermented his nascent aesthetic sensibilities watching dozens of shows at long-gone venues like CBGB and the Mudd Club. What forged his monastic commitment to art and music were not capital-R Rock bands like Led Zeppelin but the bands ÔÇ£blossoming together on the radical margins of underground rockÔÇØ like Talking Heads, DNA, and Public Image Ltd., which pursued originality over convention. By absorbing the cityÔÇÖs lively rhythms, he bootstraps himself from geeky Connecticut transplant to scene icon, overwriting his timid personality with the expressive spirit of his favorite artists. ÔÇ£It was where I could write songs, play guitar in a band like no other, write books of poetry, spend my days and nights in deep-soul streets of inspired energy,ÔÇØ he writes of moving to the city. ÔÇ£A place where I could be protected by rock and roll, where I could fall in love at any given moment.ÔÇØ

Like Patti SmithÔÇÖs Just Kids, much of this book doubles as a cultural ethnography of a city that doesnÔÇÖt exist anymore, as Moore meticulously reconstructs the nightlife, scene politics, and artistic cross-pollination that catapulted local stars like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Madonna Ciccone, Jenny Holzer, and Jim Jarmusch (all of whom Moore brushed elbows with) into national prominence. He apparently attended every consequential show and purchased every consequential record, while barely getting by in a dilapidated Alphabet City apartment through a series of odd jobs. This young man, as he reflects, was not fit for steady employment ÔÇö he would be an artist and nothing else. Early on, he flirted with being a musician-critic like Smith and even aspired to write for the seminal rock magazine Creem, which eventually led to a brief series of sweet interactions with the late Lester Bangs. You can glimpse that in the adjective-heavy, overly enthusiastic way he writes about his favorite performers: ÔÇ£a righteous celebration of hypersonic beautyÔÇØ (Bad Brains), ÔÇ£the sound of every alien artist in the city looking to find sense in a reality infused by perversion and absurdityÔÇØ (Teenage Jesus & the Jerks), ÔÇ£psychedelic heavy metal no wave rainbow spiraling into their ears and heartsÔÇØ (his own band).

An editor might have trimmed the surplus of described shows  one chapter is wholly dedicated to a raucous Public Image Ltd. gig  but the ground-floor perspective of this fertile milieu is definitely interesting. More conspicuous, the longer he goes on, is Moores emotional absence in these pages. He doesnt appear to have many close friendships, not even within the band; there is such little accounting of his relationship with Ranaldo or Shelley that around the 300-page mark, I looked up and wondered aloud, Are he and Lee  friends? He doesnt really date; by his own telling, Gordon, whom he met at age 22, was his first serious girlfriend, and hes drawn not just to her looks, her demeanor, and their mutual friendships but by what she represents. It was obvious that she was genuinely devoted to being an artist, a stance that she embodied naturally and that attracted me profoundly, he writes. Her feminism was a radical revelation to me, and it would inform my own self-awareness. He depicts himself as a loner and voyeur, hovering on the margins and waiting to be invited into some grand party of his fantasies, a mentality that serves him well for the stardom Sonic Youth does achieve. He talks about his personal feelings with a stoics remove, reserving his enthusiasm for whenever hes engaging with music.

Sonic Youth die-hards will appreciate the rigorous accounting of the bandÔÇÖs working process, from the way they selected album art through the unconventional guitar tunings they used on particular songs. But the more Moore writes, the more he circles a lacuna at the heart of his story: his relationship with Gordon. ItÔÇÖs not that he avoids her altogether, but his reticence to divulge entirely may be logistical or even legal: Moore is now married to ÔÇ£the other woman,ÔÇØ and the knottiness of how to write about the ex-wife who despises your current wife (feelings that, I imagine, are mutual) is not for me to untangle.

Yet given how much of the bandÔÇÖs experience is wrapped up with his previous marriage, the glancing way he talks about Gordon feels increasingly incomplete, certainly every time we get another story about some great concert. ÔÇ£The gathering energy of Sonic Youth and the growing intimacy of my relationship with Kim had subsumed my earlier ideas of what my life and my art should be,ÔÇØ he writes of the bandÔÇÖs chemistry taking shape. While discussing how they fell in love, he describes their respective personalities: Gordon ÔÇ£possessed a sensitivity that could be emotionally raw or coolly distant,ÔÇØ while Moore himself is ÔÇ£a younger, somewhat on-the-loose rock-and-roll boy.ÔÇØ This dynamic was reified in the bandÔÇÖs own music, both in their voices ÔÇö GordonÔÇÖs breathy and mysterious, MooreÔÇÖs flat and sneering ÔÇö and in their song material. The breadth of Sonic YouthÔÇÖs output makes it unwise to erect a barrier between ÔÇ£the Kim songsÔÇØ and ÔÇ£the Thurston songs,ÔÇØ but itÔÇÖs true that Moore did sing more of the better-known songs that conventionally ÔÇ£rockedÔÇØ ÔÇö a role that may have carried over from his marriage.

And when he does dig into some facet of their relationship, like how they fell in love or their shotgun wedding or the prickly nuances of cohabitating in the same band, itÔÇÖs instantly more compelling than whatever else heÔÇÖs just been talking about. HereÔÇÖs what passes for a juicy admission: ÔÇ£I got jealous sometimes about the way Kim gave attention to other male musicians, men whom it was obvious that she admired, either intellectually, emotionally, or both,ÔÇØ he writes. ÔÇ£She seemingly took in stride my platonic friendships with other women. Whatever feelings may have lingered within us, neither of us ever felt the need to confront the other in any accusing way.ÔÇØ He doesnÔÇÖt name names, but if you want to connect the dots, itÔÇÖs notable how much Gordon wrote about her affection for Kurt Cobain in her memoir ÔÇö and, in turn, about her disdain for Courtney Love, whom Moore seems to like just fine.

The best celebrity memoirs demonstrate a willingness to grapple with how their author is perceived and to unpack their own feelings about that perception. (The most memorable one Ive read in the last ten years is Jessica Simpsons Open Book.) One of the books most revealing passages is when Moore describes hanging a calendar bearing a cheesy pinup girl in the apartment he shares with Gordon, on which he scrawls a bit of punk art poetry. Whatever clever commentary he intends is received differently by Gordon, who takes that bit of writing and turns them into the lyrics for Flower (Theres a new girl in your life  hanging on your wall), which would appear on their 1985 album, Bad Moon Rising. In this bit of lyrical interplay, he writes, lay the seed of a conflict in our relationship, one that would remain unspoken but that would someday contribute to its dissolution. Moore, despite his repeatedly stated feminist bona fides, couldnt deny [his] attraction to the nude calendar girl. And though he believes he can turn his lurid appreciation into a statement of solidarity and a sublimation of beauty, the truth is that its only so interesting for a straight man to be turned on by a sexy woman  something Gordon picks up on instantly and turns into her own, more thoughtful art.

ItÔÇÖs a shrewd bit of self-analysis ÔÇö even if unflattering ÔÇö about his inability to lose the wandering eye that would one day propel him toward his affair. ÔÇ£But the two of us never talked about it outright, only through our songwriting,ÔÇØ he writes. ÔÇ£It wouldnÔÇÖt be the last time that music was the mode of dialogue in our relationship.ÔÇØ This, too, is a recurring idea in GordonÔÇÖs book ÔÇö how playing in the same band generated an unbelievable musical chemistry that allowed husband and wife to also sidestep any out-loud conversations about what was happening between them. Perhaps his memoirÔÇÖs relative elision of their relationship, compared with the dutiful recounting of everything Sonic Youth ever accomplished, mirrors that real-life reticence.

The unwritten implication is sobering: By focusing so much on music and art, he neglected his relationship and thus changed the way his music and art would be perceived. For all his understanding of rock-and-roll mythology, he doesnÔÇÖt seem to grasp how his fansÔÇÖ experience of Sonic Youth was also wrapped up in his marriage ÔÇö how much their music seemed to reflect the collaboration, respect, and passion between Moore and Gordon, palpable every time they took the stage, just as Moore himself felt watching Patti Smith perform with her husband when he moved to the city. Perhaps thereÔÇÖs something admirably old school about the pointed separation of oneÔÇÖs public and personal life, and with it a refusal to explain all of your motivations; with respect to the eloquence of GordonÔÇÖs memoir, itÔÇÖs impossible to write a completely objective record of a relationshipÔÇÖs demise. In the end, if Sonic Youth leaves us with nothing else but their amazing discography, itÔÇÖs not the worst outcome ÔÇö merely a disappointing one, considering how much more they once represented.