It’s that time of year again, when Vulture’s critics embark on our messiest annual tradition: the finalization of our Top 10 lists. Here are the best movies Bilge Ebiri and Alison Willmore saw in 2024.

Bilge Ebiri’s Top 10 Films

Popcorn buckets. They gave us fancy popcorn buckets. All we really wanted from America’s theater owners was for them to project the movies properly, and instead they gave us fancy popcorn buckets. Dune: Part Two sandworm popcorn buckets. Gladiator II helmet popcorn buckets. “Headpool” popcorn buckets. Nosferatu miniature-coffin popcorn buckets. Meanwhile, we had to contend with armies of overgrown children photographing (and sometimes recording) the screen on their phones. Apparently, pickleball and zip lines are next on the menu?

But maybe it’s working. The predictions for theatrical moviegoing in 2024 were quite dire — partly because of the production and release delays owing to the 2023 Writers’ Guild and SAG-AFTRA strikes, partly because people seemed to be losing interest in trusted franchises — and, after the initial disappointments of The Fall Guy and Furiosa, it did seem like the box office was headed for disaster. But then things changed, and a lot of people actually did go to cinemas this year. So, all the nonsense that those of us who imagine ourselves to be Serious Moviegoers™ have to contend with are just the byproducts of what happens when the masses decide they want to see movies in theaters. And perhaps the most surprising thing about film in 2024 is the fact that I was personally okay with all the many annoyances of the theatrical experience. Being in crowds with people means learning to accept our differences. Anyway, go see Nickel Boys. It’s great.

10.

Hit Man

So much of the conversation around Richard Linklater’s breezy hired-un-assassin comedy was understandably focused on Glen Powell’s incipient stardom. (Okay, Twisters was a huge domestic hit — can we finally call him a movie star? They just held a Glen Powell look-alike contest in Austin. Does that count?) But the film was also one of Linklater’s most compelling meditations yet on the mutability of identity, interspersing pop-philosophical digressions into the sex-drenched story of a boring nobody refashioning himself into a stud after getting roped by the New Orleans police department into posing as a hired killer. It’s still a huge shame that this film didn’t get the proper theatrical release it deserved; watching it with an audience was one of the highlights of the festival circuit in 2023.

➼ Read our full review of Hit Man.

9.

Ghostlight

Some of the greatest works of art have been produced about the consoling power of other works of art. Alex Thompson and Kelly O’Sullivan’s absorbing drama follows a family that has suffered unimaginable loss, as they’re swept up in an amateur production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. As charmingly rickety as this small, local theatrical production might be, this new angle on old material revitalizes the play’s immortal poetry. Words that we’ve heard many times over the years — words that have become almost commonplace — suddenly gain renewed power. The similarities between the play and this family’s life are almost too neat, but O’Sullivan and Thompson shoot and edit with an eye towards the mystical. (Note the title.) Art thus becomes not just a form of consolation, but a conjuring, a communion with the infinite.

➼ Read our full review of Ghostlight.

8.

No Other Land

Much of the discussion around No Other Land has understandably centered around its inability to find distribution. Somehow — somehow! — a documentary about Israel’s attempts to extinguish the West Bank village of Masafer Yatta couldn’t get picked up, despite mountains of awards and endless festival appearances. But let’s also not overlook the sheer intelligence of this movie, which was made by a collective of Israeli and Palestinian filmmakers (two of whom, Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham, also happen to be its protagonists). More effectively than any other film about this subject, No Other Land lays bare the methods by which a community is extinguished — not through one mass expulsion (which would attract undue international attention) but by a yearslong drip-drip-drip of bulldozed homes, destroyed wells, and late-night arrests. This is an astute usage of the cinematic medium’s ability to compress time and expose epochal cruelties.

➼ Read our full review of No Other Land.

7.

Horizon: An American Saga — Chapter One

I’ve seen chapters one and two of Kevin Costner’s civilizational epic about Western expansion (chapters three and four have yet to be shot) and it’s clear that the writer-director-star is creating something extraordinary. Whether he’ll get to finish it (and whether we’ll get to see it) is a question sadly left to the fickle whims of production and distribution executives. In the age of movies being split into multiple parts, Horizon is the one that perhaps suffers the most. Witness all the critics bewildered by the fact that its opening chapter feels like … an opening chapter. Costner sets up a story that seems like it’s going to adhere to a traditional narrative trajectory, but he then uses the multi-part structure to complicate things. Chapter two largely focuses on the female characters of this saga, who felt like they were in danger of being sidelined in chapter one. Meanwhile, people we had pegged as heroes act like careless, unfeeling monsters, and the obvious villains show surprising moments of humanity. One day — I suspect, I hope — Costner’s full canvas will exist in all its emotional complexity and visual magnificence.

➼ Read our full review of Horizon: An American Saga — Chapter One.

6.

Girls Will Be Girls

Shuchi Talati’s coming-of-age story, set at an elite boarding school in India, is so thoroughly absorbing that you might find yourself checking the clocks onscreen to find out what time it is in real life. In its broad strokes, it’s a simple (and potentially predictable) story about an overachieving young girl who falls for the new boy in school and finds herself slipping. What makes it so alive is the delicacy and honesty with which each character has been drawn and performed. It could have easily become yet another movie about victims and villains, or about overbearing parents and rebellious kids. Instead, it has the aura of truth, which makes it riveting.

➼ Read our full review of Girls Will Be Girls.

5.

Universal Language

I became mildly obsessed with Matthew Rankin’s film at Cannes (where it stood head and shoulders above most of the other pictures playing at the festival) in part because of the subtle bait-and-switch at its heart. The movie is set in an imaginary Winnipeg that is steeped in Persian culture (and where everyone speaks Farsi). That seems like an interesting and surreal conceit — and it is — but the film develops that idea into something far more poetic and moving than might be expected. At the heart of the film is a journey home taken by a man named Matthew Rankin (played by Rankin himself) who has not seen his mother for many years. But someone else now lives in his childhood home, and his aging mom now imagines that another man is her son. Rankin uses the cultural blending to create a film that exists somewhere between dry Canadian humor and magical realism, and his goofy conceptual ideas allow him to oscillate between sly deadpan and the fondly remembered humanism of New Iranian Cinema.

➼ Read our full review of Universal Language.

4.

The Fall Guy

I’m not sure I had more pure fun at any movie this year than David Leitch’s comic-romantic action ode to the stunt profession, which took a shaggy-dog noir tale and turbo-loaded it with spectacular feats of physical and vehicular achievement. The stunts of course were the film’s designated high points, from a record-breaking cannon roll to a climactic, already-legendary high fall. But what really made the movie so involving was the terrific chemistry of leads Ryan Gosling and Emily Blunt. Movie stars being movie stars — what a novel concept.

➼ Read our full review of The Fall Guy, behind-the-scenes look with the stunt team, and conversation with director David Leitch.

3.

Green Border

Agnieszka Holland’s epic about the plight of refugees who’ve been turned into political hot potatoes prompted controversy in her native land last year, as far-right Polish politicians decried her for daring to show the cruelty of their treatment of these people. In Green Border, desperate refugees are beaten, robbed, and thrown — sometimes literally — back and forth across the boundary between Poland and Belarus. Holland, who fled Communist Poland in the 1980s, has always had a feel for the stateless, for people who escape their homelands only to find themselves unwelcome elsewhere. Exhaustively researched, her multi-character tale gives us the perspectives of the refugees, the border patrols, the activists, and ordinary people caught in the middle of it all. She tackles one of the great crises of our time with compassion, clarity, and outrage. The result is the most terrifying film of the year.

➼ Read our full review of Green Border.

2.

Nickel Boys

The best American film of the year is also the most revolutionary, though I’m not sure any other director could have pulled off what RaMell Ross does here. Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel about two Black teenagers being brutalized at a reform school in the Jim Crow South here becomes a startling meditation on perspective and empathy. Ross’s first-person camera allows us to experience his protagonists’ lives through their eyes, which in turn calls into question how such stories of suffering and outrage have been presented in the past. The ambition here is staggering. Ross seeks to do nothing less than to change how we see the world. Shockingly, he succeeds.

➼ Read our full review of Nickel Boys.

1.

Close Your Eyes

What a miracle it is to have another feature film by the great Victor Erice, the legendary Spanish director whose last feature came out in 1992 (which was a decade after the previous one). And what a film his latest turned out to be: an existential (and melancholy) mystery about the search for an actor who mysteriously vanished decades ago. Looking for him is the director whose own career was cut short by the man’s disappearance. With his elegant control of the frame and his precise mastery of mood, Erice is an artist of suggestion: Close Your Eyes eventually builds to a series of scenes that subtly question the nature of happiness and memory, what it means to recognize someone, and in turn to be recognized by them. It’s a proper masterpiece by one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

➼ Read our full review of Close Your Eyes and interview with director Victor Erice.

Alison Willmore’s Top 10 Films

People loved Megalopolis, hated it, puzzled over it, clipped it into memes, and tried to astroturf it into a camp classic, but, most importantly, they cared about it even though it featured none of the qualities you’d expect of a breakthrough work in these noisy times. What that meant, to me, is that audiences have been craving ambition, which is something that movies, caught forever between art and commerce, haven’t been in a place to deliver. There are big entertainments and small personal films, but to grapple with weighty ideas on a large canvas? You have to do what Coppola did and pony up $150 million of your own money (something I wouldn’t advise, personally). Or what Brady Corbet did with The Brutalist, making something grand and sweeping on $10 million by going abroad, making ethical compromises, and burning yourself out. The Brutalist also wasn’t one of my favorites, but I admired the hell out of what Corbet set out to do with his film, which in a coincidence is also about an architect trying to achieve his vision in a landscape of callous capitalism — an idea that seems to be very 2024.

10.

Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl

2024 has been a banner year for variety in animated animals, from the bickering island fauna of The Wild Robot to the misfit pack in Flow to the CGI creatures in Mufasa: The Lion King. But none of them could provoke the joy that bubbled up inside me upon seeing Gromit’s familiar canine face on the screen again. Gromit, the long-suffering pet, friend, assistant, and savior of the cheerfully oblivious inventor Wallace, may be made of plasticine, but he remains more expressive than most flesh-and-blood humans. Despite the passing of Peter Sallis, who provided Wallace with his round Yorkshire vowels for over 20 years, the stop-motion world that Aardman revisits feels comfortingly unchanged, from the chunky knit of Wallace’s sweater vest to the expanse of Gromit’s garden. Vengeance Most Fowl also brings back an old foe in the form of Feathers McGraw, the dastardly penguin and apparent master of disguise, though its real villain is our unexamined acquiescence to the convenience of technology, as represented by Norbot, the gnome assistant that Wallace creates and doesn’t realize has turned evil and created an army. Why would you ever choose something slickly digital when you can luxuriate in the handwrought textures of Wallace and Gromit’s cozy brick home, with its floral wallpaper, Rube Goldberg–esque inventions, and steaming cups of tea?

9.

Red Rooms

Pascal Plante’s relentlessly chilly film begins like a thriller, then reveals itself to be something less conventional and more upsetting: a horror story about getting hopelessly lost in the sauce. As blank-eyed model Kelly-Anne, living a sparse existence of screens and solitary workouts in a condo tower high above Montreal, Juliette Gariépy initially comes across as the more rational of Red Rooms’s two women, who meet at the trial of a man accused of murdering three teenage girls for paying customers on a livestream. Kelly-Anne’s not a groupie like Clémentine (Laurie Babin), who spouts off heated defenses of the man that aren’t restrained by rationality. But in a reveal that’s all the more bracing for being transmitted via Plante’s aloof long takes, Kelly-Anne turns out to have gone so deep into the case that she’s become a part of it, the line between legal voyeur and snuff-video connoisseur crossed before the film even began. Red Rooms is a brilliant depiction of a contemporary affliction — getting so involved in an online reality that you rewire your brain’s pleasure centers and lose all moral orientation.

➼ Read our full review of Red Rooms.

8.

Union

The streaming era has simultaneously sucked the vitality out of documentaries and made them more dominant than ever, thanks to a never-ending barrage of docuseries recapping existing reporting over a bloated run time. So it fits that Brett Story and Stephen Maing’s Union, a doc that is stylistically haunting, politically urgent, and guided by its subjects’ journeys rather than a predetermined structure, couldn’t find a distributor because no one wanted to alienate Amazon, the massive corporation and, among other things, the streaming service at its center. Union is a rousing, intensely bittersweet look at the most underdog of labor efforts, following leader Chris Smalls and his dedicated colleagues in a battle to launch a brand-new union at the multinational company’s Staten Island warehouse without the help of established organizations. It sometimes feels like a film about a group of people having to invent organizing from scratch in a world of multinational giants that, as the film emphasizes with pointed shots of enormous cargo ships and conveyor-belt-lined spaces, would prefer to treat their employees as just more replaceable component parts.

➼ Read our full review of Union.

7.

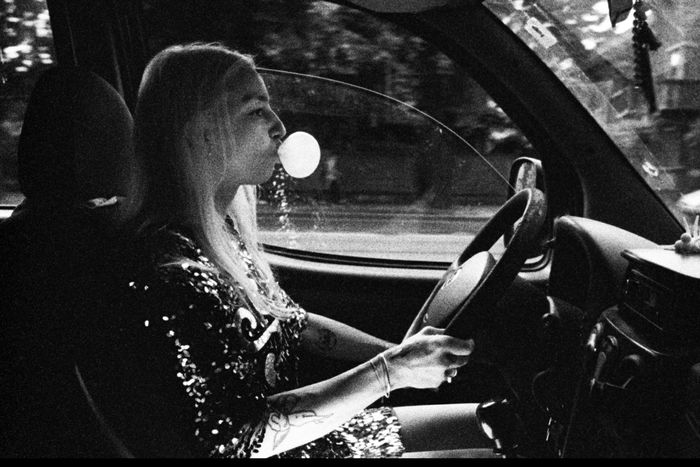

Anora

Sean Baker is known for his focus on sex workers and for his facility with first-time actors, but his most distinctive quality as a filmmaker may also be his -most underdiscussed. He has a singular way of capturing the camaraderie of people united by a common cause, whether that cause is a meth habit, or hours of unsupervised playtime at a run-down motel, or, in Anora, the search for a Russian oligarch’s son, who’s gone on the lam after his parents got word of his impulse marriage to a stripper. Baker’s latest careens as thrillingly as the Coney Island Cyclone from comedic meet-cute to delirious romance to home invasion to merciless bubble pop. But the section that I keep thinking about is the one in the middle, when the tremendous Mikey Madison spends the night driving around Brooklyn looking for her wayward husband in the company of three henchmen. Bent miserably over a meal at an all-night diner, they become a provisional unit at the center of their own highly specialized sitcom, bickering and complaining and trying to figure out what to do next. Baker would never romanticize these brief moments of rapport — the ending, in the car in the snow, feels like a deliberate rebuke of that impulse — and yet there’s something so ruefully human about those bursts of temporary warmth and humor. In all its grandeur and chaos, what holds Anora together is not solidarity but an acknowledgment that everyone is being buffeted around by the forces of global capital.

➼ Read our full review of Anora, interview with star Mark Eydelshteyn, interview with the supporting cast, close read of filmmaker Sean Baker’s politics, and our analysis of the film’s ending.

6.

Juror #2

It took a 93-year-old to direct the movie that best encapsulates our current crumbling sense of duty toward one another, and if Clint Eastwood’s courtroom drama ends up being his last as a filmmaker, it’s a hell of a way to go out. Juror #2 is a rhetorical high-wire act about a man trying to 12 Angry Men a jury into clearing his conscience without incriminating himself. But its real power comes from how divorced its characters all feel from the high-minded ideals of the institution they’ve been enlisted to serve. Jury members are impatient to settle on a verdict so they can go home, the prosecutor is using the case to cement her campaign for district attorney, and witnesses tell the police what they want to hear in order to feel useful. At the film’s heart is a bright-eyed Nicholas Hoult as a recovering alcoholic and soon-to-be dad who hews to his conviction that he’s a good person as though that were a quality that could exist separate from his own actions, up to and including the possible death he caused. Juror #2 doesn’t make him a villain so much as it makes him an example of the enormous uphill battle of doing the right thing in a world where everyone’s ability to get by is so precarious that self-interest starts to feel like the only reasonable choice.

➼ Read our full review of Juror #2.

5.

The Substance

The best scene in Coralie Fargeat’s outrageous black comedy isn’t one of the many gleeful instances of body horror or the plastic-slick re-creations of the lascivious showbiz gaze. No, the best scene is the one in which Elisabeth Sparkle, the aging star played by a go-for-broke Demi Moore, tries and fails to go on a date with an old classmate. She puts on a dress that’s a little too much, does her makeup, puts on her coat, reaches for the door — and can’t quite bring herself to open it, because lurking by her window is a billboard of the younger version she’s killing herself to get back to, all dewy skin and taut flesh. She goes back, she redoes and then claws at her face in the mirror, she glares at the person she’s had the temerity to age into, and at that moment we understand that she’s never going to save herself, and that after years of being subjected to Hollywood standards, she’s constructed a prison in her own mind from which there’s no escape. The Substance gives us splitting spines and eyeballs doubling in sockets and mutants spraying blood all over an audience in formalwear (that crying child, I cackled!), and it’s all fantastic and excessive, but at its core is a genuine emotional rawness about the ways in which we become warped and addicted to the systems that harm us.

➼ Read our close read of The Substance and our piece on the reaction to the divisive film at the Cannes Film Festival.

4.

Nickel Boys

The first-person perspective that RaMell Ross employs for Nickel Boys isn’t a gimmick or a self-imposed challenge, but a way of cracking open a portrait of institutional abuse and survivor’s guilt like nothing else. Nickel Boys doesn’t just immerse you in the story of a Black teenager who’s wrongfully sentenced to serve time in a brutal Florida reform school from which many boys don’t emerge alive. It slips you into his existence, every sense memory and flash of developing consciousness, and depicts how racism enters his life as an early and jarring intrusion that will eventually destroy his plans with an indifference that’s just as monstrous as active cruelty. Ross was a documentarian first, and he turns his Colson Whitehead adaptation into a rich symphony of tangible details both beautiful and terrible. It culminates in an astounding rush of imagery during what’s not a twist so much as a heart-wrenching revelation that turns our understanding of Ross’s formal choice on its head again.

➼ Read our full review of Nickel Boys.

3.

Challengers

I’ve seen Luca Guadagnino’s tennis love-triangle movie three times now, but I’ve watched the final set maybe a dozen times on its own — via links, and on YouTube, and over the shoulders of fellow passengers on seat-back screens during a flight. Challengers is deliriously horny and deliciously fun throughout, from the stretch in which Mike Faist and Josh O’Connor are doubles partners and jerk-off buddies chasing a teenage Zendaya to the present day, in which they’re all miserable adults resisting their natural configuration as a triad. I love the way Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s throbbing techno theme turns scenes in suburban parking lots and anonymous hotel lobbies into cinematic showdowns. I love Faist’s gawky beauty and O’Connor’s unwashed irresistibility and Zendaya’s surly confidence. But more than anything else, I love that Challengers commits so thoroughly to the idea of its romantic shenanigans as extensions of the game that it pulls off that ludicrous, perfect ending — sweat dripping, slow motion, secret grins of satisfaction, and the camera in the POV of the goddamned ball. Hold on, I’m going to watch it again.

➼ Read our review of Challengers, review of Zendaya’s movie performance; and explanation of who won in the ending scene.

2.

Hard Truths

Mike Leigh’s portrait of a compulsively angry Londoner is a companion piece to his 2008 Happy-Go-Lucky, which was centered on an almost pathologically cheerful teacher played by Sally Hawkins; the films are a fascinating Janus-faced double feature of personality extremes. But Hard Truths is also shockingly resonant on its own as a depiction of how pain can bubble up within you and then burst outward, strafing anyone unlucky enough to be nearby. Pansy, the wife and mother played with astonishing intensity by Marianne Jean-Baptiste, is without question depressed and desperate, but she’s also harboring festering wounds from childhood, hurts and resentments she can barely bring herself to talk about with her sister, the only one who could understand. Leigh is unsparing about the barely coherent bile that gouts out of Pansy as she moves through the world, with her husband and son cowed after years of being her most convenient targets. But Leigh is also miraculously tender with this unendingly difficult woman, never more so than as she sits in her car after an outburst, afraid and looking like she wants someone to save her from herself. When someone does, it’s a man who answers her abuse with his own in a way that almost gets her to smile, if only because she’s not alone in her unpleasantness.

➼ Read our full review of Hard Truths.

1.

Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World

Angela, played by Ilinca Manolache, is a tiny, foulmouthed, fearless PA who might as well be the mascot of this turbulent year — a woman who’s being ground into the dirt by her job but who nevertheless retains the ability to find life surprising. Radu Jude’s exuberant comedy is savage and insightful, a film about how we live today that’s also about how nothing really changes for the average worker. What starts as a parallel between Angela’s overlong day spent casting a corporate safety video and excerpts from a Communist-era drama about a harried female taxi driver converge into a single narrative when Dorina Lazar, the star of the 1981 film, turns up in character as one of Angela’s interviewees. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World creates the feeling of something on the verge of devolving into chaos, cutting between clips of Angela’s profane TikToks and selections from the older movie and digressing into cameos from Uwe Boll and the inconvenient aftermath of a hasty quickie. But Jude is in complete control, and that’s never clearer than during the final section, when the video shoot plays out in a long fixed take that is such a bitterly funny payoff of so many elements established before that it feels like a miracle — or just the greatest film of the year.

➼ Read our full review of Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World.

Other Movie Highlights From This Year

Throughout 2024, our critics maintained “Best Movies of the Year (So Far)” lists. Some of those selections appear above in our Top 10 picks. Below are more of the films (but not all) that stood out to them this year. Movies are listed by U.S. release date, starting with the most recent.

Conclave

Edward Berger’s Conclave is adapted, quite faithfully, from Robert Harris’s 2016 novel, and it combines the pulp velocity of a great airport read with the gravitas of high drama. It follows the ritualistic backstabbing that goes on during the election of a new pope as a group of men steeped in tradition try diligently to shut out the modern world — even though that world is still there, outside the windows of the Vatican, constantly felt in everything they do. The film features a perfect role for Ralph Fiennes as the dean of the College of Cardinals, a deeply conflicted man who admits that he values doubt and abhors certainty, even as he becomes more obsessed with controlling the outcome of the election. Amid the stately ceremony, Berger finds ways to insert gradually escalating tumult and cattiness. The priests’ fragile isolation isn’t just a psychological element. We sense throughout that the outside world is undergoing turmoil, of which these men are mostly unaware — though we suspect they soon will be, both metaphorically and physically. Berger expertly milks that anticipation, then nails several artfully heated and lively climaxes. —Bilge Ebiri

➼ Read our full review of Conclave and close look at the twist ending.

Dahomey

Mati Diop’s second feature is a documentary about the repatriation of 26 royal artifacts from France to Benin, though that description doesn’t do her urgent, mysterious film justice. In just 68 minutes, it conjures up a dreamlike inner monologue for the looted treasures, depicts their journey across the ocean to be displayed and celebrated in Cotonou, and drops into a heated debate among university students about the significance of the objects. Dahomey weaves together considerations of history, colonialism, and reparations, all while giving due to the enigmatic presence of artworks restored to a homeland that, however changed, remains where they belong. —Alison Willmore

➼ Read our full review of Dahomey and interview with director Mati Diop.

Rumours

With Rumours, the legendary Canadian director Guy Maddin, working with his regular collaborators Evan and Galen Johnson, has made what might be his funniest film to date. But, as always with Maddin, the humor is somewhat rarefied. Rumours follows the leaders of the G7 as they get lost in a German forest and are beset by mysterious ancient figures while also being consumed by their own strange passions. The humor does require some vague familiarity with the way these public international get-togethers — be it the G7 summit, the NATO summit, or assorted U.N. gatherings — never result in anything resembling real actions or solutions, instead issuing countless weak-willed joint statements and working papers and other forms of diplo-blather. And while the danger of movies based on conceptual wit is that they will lose steam as things proceed and the filmmakers run out of ideas, Maddin and the Johnsons thankfully develop their story — goofy and absurd though it may be — so that these constant digs at our ineffectual leaders do coalesce into something meaningful and alarming. But still hilarious: Just because we’re choking on our laughter doesn’t mean we’re not still laughing. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Rumours.

The Outrun

Saoirse Ronan gives one of her most transcendent performances in Nora Fingscheidt’s windswept drama, playing a woman trying to rebuild her life after returning to her childhood home in the Orkney Islands. The film, based on Amy Liptrot’s 2016 memoir of addiction and recovery, drifts back and forth between its protagonist’s present and her past as an out-of-control alcoholic in London. It also hops along different periods in her rehabilitation, never quite following a clean and steady narrative line, which puts quite a bit of responsibility on Ronan’s performance. We chart her character’s progression through her physicality. And the spectral light in Ronan’s eyes speaks volumes; this young woman is terrified of the world around her. Maybe that’s also why the film is filled with details about the natural world, including animated sequences involving mythical sea beasts thought to reside in the waters off the Orkneys. Such legends speak to the fundamental helplessness of humans in the midst of nature, but they also hint at a fantasy of power: If another being can exert such command over our worlds, then so perhaps can we. That idea — full of tension, frustration, possibility — fuels the whole film and Ronan’s performance specifically. The Outrun is ultimately about how our search for certainty and control all too often results in the loss of what little we do have.

➼ Read our full review of The Outrun.

Sleep

Sly, dark, and deviously well constructed, Jason Yu’s feature debut is a horror comedy about somnambulism that’s really more about marriage. Soo-jin (Jung Yu-mi) is an office worker and Hyun-su (Lee Sun-kyun) is a struggling actor, and as the couple approaches the arrival of their first child, their commitment to one another is challenged by the increasingly alarming sleepwalking condition Hyun-su develops. Soo-jin’s determination to protect her husband starts turning into an urge to protect others from him once their baby arrives, and Yu ably ramps up the dread while showing how Hyun-su’s hapless sleeping menace meets Soo-jin’s sleepless anxiousness. —Alison Willmore

➼ Read our review of Sleep.

The Wild Robot

Based on the children’s book by Peter Brown, Chris Sanders’s new animated film presents a somewhat familiar, comforting, warmhearted tale. But then you look at the movie — really look at it, as you might a painting — and a whole new world opens up. In telling the story of a relentlessly task-oriented robot (voiced brilliantly by Lupita Nyong’o) that’s wound up on the edge of a dense forest in a remote island in the middle of nowhere, Sanders creates a visual dissonance that almost subconsciously insinuates its way into our brains and feeds the central idea of the film. And it’s hypnotic. The environment and the creatures have been painted with rough brushstrokes, running counter to the polished look of modern computer-animated films. The robot, however, is all sharp angles and sleek surfaces — until she starts to change and learn about what it takes to become a mother for an orphaned gosling who is just as much of an outcast as she is. The tale of the robot becomes a deeply relatable tale of inadequacy: How far can our longing to love carry us if the world refuses to acknowledge it, and if we ourselves lack the means to express it? The film’s visual imagination, combined with Nyong’o’s vocal performance, turns a heartwarming family film into an unforgettable one. —Bilge Ebiri

➼ Read our full review of The Wild Robot and interview with director Chris Sanders.

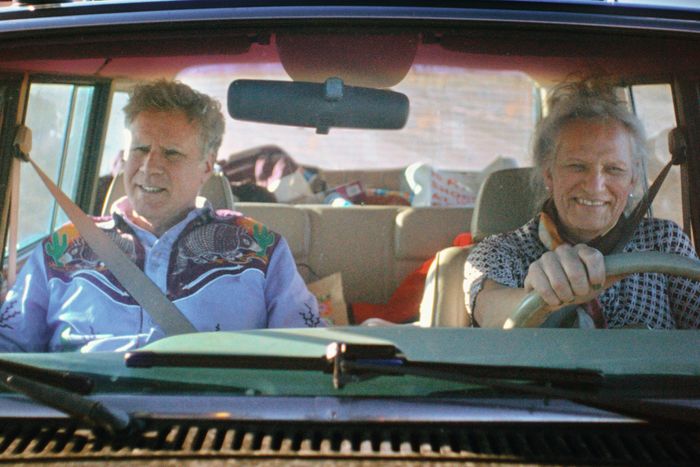

Will & Harper

A very funny movie about two comedians stuck on a road trip together that also happens to be a tender documentary portrait about the friendship between Will Ferrell and his trans best friend Harper Steele, Josh Greenbaum’s film could potentially find purchase with audiences that would otherwise avoid a movie with a subject like this. Ferrell and Steele both started at the same time on Saturday Night Live in the 1990s — one as an actor, the other as a writer — long before Steele transitioned at the age of 61. As Ferrell tells it, the Iowa-born Steele was something of a tough guy at the time, someone who loved drinking “shitty beer” and hitchhiking and road-tripping across the country. The idea for the documentary grew out of Ferrell’s desire to accompany Steele on her first trip across the country after transitioning. Greenbaum, who directed 2021’s Barb & Star Go to Vista del Mar and last year’s Strays, clearly has a feel for buddy comedies and road movies. The film’s most powerful achievement is perhaps also its most basic: the simple sight of two friends talking, openly and gently, about all the things on their minds. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Will & Harper.

A Different Man

Aaron Schimberg’s unclassifiable conversation-starter is part noir, part sci-fi, part comedy, part drama. Sebastian Stan plays Edward Lemuel, a shy, struggling actor with a facial disfigurement whose life changes when an experimental treatment miraculously removes the tumors covering his head. Then he meets Adam Pearson’s Oswald, who has the same condition. Unlike Edward, however, Oswald is a bon vivant comfortable in his own skin — a great dancer, a karaoke master, and a ladies’ man who politely takes everything from the now handsome but increasingly surly and resentful Edward. It’s a star-making turn for Pearson, an actor with fibromatosis, whose delightful personality directly inspired Schimberg’s film. Stan, also wonderful, appears in his early scenes in an expertly made prosthetic mask; when Pearson shows up, it’s a delightful surprise not just for the characters onscreen but for the audience as well. The film essentially becomes a conversation about the portrayal of disability onscreen — a hilarious, moving, atmospheric one. —B.E.

➼ Read our review of A Different Man and interview with star Adam Pearson.

Matt and Mara

I didn’t click with Kazik Radwanski’s last film, Anne at 13,000 Ft., with its depiction of a young woman with an undiagnosed mental illness that struck me as a little too much like someone’s recollections of their “crazy” ex. But Matt and Mara, his new feature, manages to be a very different beast while reuniting the Canadian director with Anne star Deragh Campbell. She plays Mara, a poetry professor, while filmmaker Matt Johnson plays her college friend Matt, who’s now a successful (if also somewhat notorious) novelist. The difference, I think, is that Matt and Mara very much exists with its female lead, rather than observing her like a butterfly pinned to a corkboard, examining her restlessness in her marriage to a musician named Samir (Mounir Al Shami), her state of mind as a new mother, and her insecurities about her stalled-out writing career. In reuniting with Matt and starting an ambiguous flirtation with him, Radwanski deftly portrays someone toying with blowing up her life, all through undercurrents in delicately realistic conversations. —A.W.

My Old Ass

Megan Park’s coming-of-age film takes a magical realist premise — what if you could go back and give advice to your younger self? — and runs with it in surprisingly heartfelt ways. A terrific Maisy Stella is 18-year-old Elliott, who during her last summer at home before college unexpectedly connects with her 39-year-old self (played by Aubrey Plaza) thanks to some psychedelic mushrooms. Rather than flesh out the sci-fi potential of this premise, Park uses it to explore her young protagonist and to delve into the question of whether it’s better to avoid heartbreak when that heartbreak comes at the end of something wonderful. As a bonus, My Old Ass is set in the most idyllic lakeside Canadian community you can imagine. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of My Old Ass.

Rebel Ridge

Jeremy Saulnier is our current master of the slow-burn action movie, and Rebel Ridge might be his tightest, most characteristic work to date. It’s all about a man trying to avoid violence — and the more he avoids it, the more the viewer’s bloodlust grows. We first see former marine Terry Richmond (Aaron Pierre) speeding down a country road on a bicycle before the local cops knock him over with a car and detain him. The police seize a giant wad of cash from his backpack — money he’s rushing to bail out his cousin, who’s being held on a minor drug charge. It’s all quite infuriating, especially once we discover that what the cops are doing is all legal. Rebel Ridge at times seems to have been made specifically to inform the American public about the injustices of civil asset forfeiture; Terry even gets an aspiring-lawyer sidekick, Summer (AnnaSophia Robb), who works for the county clerk and conveniently explains the situation whenever context is required. Saulnier builds tension well, but he also elegantly choreographs the havoc when it does come. And anticipation leads to investment. Rebel Ridge is not even all that violent, but the limb-breaking and face-pummeling in this movie are some of the most satisfying in recent memory. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Rebel Ridge and interview with filmmaker Jeremy Saulnier about the film’s ending.

My First Film

Zia Anger’s film is a documentary and a drama that reflects on the past while re-creating it in scripted form. It’s a look back at an unfinished indie that Anger set out to make on the cheap with some friends when she was in her 20s, with Odessa Young playing the baby filmmaker and other actors portraying her cast, crew, and then-boyfriend. It’s a rueful depiction of being young and careless with yourself and with the safety and time of others, at throwing yourself into art that no one ever sees, and at thinking of a film as something you use others to make rather than as a collaboration. But the boldest thing it does is draw a connection between Anger’s failed feature and the abortion she underwent around that time, an audacious, shockingly tender linkage that highlights the nurturing aspect of the respective endings. —A.W.

The Killer

John Woo finally released that American remake of The Killer that’s been in the works almost since the first one premiered back in 1989. But it would be crazy to expect the 77-year-old Woo to try and make the same movie again. Luckily, he hasn’t. This new, half–gender-flipped version of The Killer, set in France and starring Nathalie Emmanuel as the expert assassin and Omar Sy as the cop obsessively pursuing her, has roughly the same plot outline as the original but a totally different mood. It skips the florid romanticism, the thick atmosphere, the grand mythmaking, opting instead for a breezy, silly modesty. It’s fun, ridiculous, and deliriously violent in its own right. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of The Killer.

Strange Darling

JT Mollner’s thriller unfolds in chapters told out of order, a device that at first feels like it’s meant to bring to mind the ’90s heyday of Pulp Fiction knockoffs but turns out to have a sly purpose to it. There’s a woman played by Willa Fitzgerald and a man played by Kyle Gallner, and while the film starts off with the former running, bloodied, from the latter, each new section makes us reevaluate the relationship between the two characters as well as who we think they are. Strange Darling is buoyed by strong performances by its lead, but what makes it such a gratifying marvel is its ingenious construction, which manages to keep you unbalanced until the very end. —A.W.

Between the Temples

In prolific indie filmmaker Nathan Silver’s latest, Jason Schwartzman plays Benjamin Gottlieb, an upstate cantor who has lost his voice because he’s mired in grief. After a suicide attempt and an altercation at a bar, he’s comforted by the almost-angelic presence of Carla O’Connor (Carol Kane), who was his music teacher back in elementary school. It turns out she wants to finally have her bat mitzvah, because she never got one as a child. Ben and Carla’s growing closeness eventually poses something of a problem for just about everyone around them. This could easily become the stuff of high-concept shenanigans, but Ben’s growing bond with Carla actually serves as a way for him to flee the humiliation that seems to lurk around every corner. Pairing Schwartzman with Kane turns out to be inspired casting: Here, two iconic oddballs from different eras of American cinema suddenly find each other, and their combined chemistry sends the movie into surprising emotional directions. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Between the Temples.

Daughters

The new Netflix documentary Daughters, directed by Angela Patton and Natalie Rae, follows the organization of a father-daughter dance between inmates at a Washington, D.C., prison and their girls, who range in age from 5 to their mid-teens. This could have easily been a standard-process doc, about the logistics and bureaucracy involved in organizing something like this, and it might have been interesting as such. But Patton and Rae choose instead to focus on the indelible faces at the heart of their tale as the girls and the dads anxiously await and prepare for their big day. The accrual of human detail pays off masterfully when we get to the dance itself, especially when the girls see their fathers for the first time. It’s only in the film’s final act that we discover that Daughters has been a longitudinal documentary all along — that this dance happened in 2019 and that these girls and their fathers have done more years of living since then. Arguably, these final scenes are the most devastating because they underscore the basic truth the entire film has been building up to: Time is the most precious thing we have. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Daughters.

Trap

It’s always nice when M. Night Shyamalan remembers to have fun. His recent career renaissance has been marked by a more playful approach to dark themes than the more serious, somber works of his early success. In Trap, he throws obsequious girl dad and occasional serial killer Josh Hartnett into a pop concert with his superfan daughter, then reveals that the concert is a huge operation designed to catch him. The concept is ridiculous, and Shyamalan knows it. He adorns the film with odd stylistic choices (close-ups addressed to the camera, in meme-friendly fashion) and wild, narratively implausible scenes. The movie is a hoot, but the director has lost none of his heart: The pop star is played by his own daughter, and in Trap’s goofily suspenseful sequences, we sense the anxieties of a man who fears he hasn’t paid enough attention to his family in his quest for success. —B.E.

➼ Read our review of Trap, essay about M. Night Shyamalan’s career, and close read of Josh Hartnett’s performance.

Dìdi

Sean Wang’s directorial debut is both tender and frank about how rough it is to be 13. Chris Wang (Izaac Wang), the protagonist, spends the summer between middle and high school bombing with his crush, alienating his friends, and taking out his frustration on his immediate family members. Steeped in the online and real-world texture of the East Bay area in 2008, the film is a painfully recognizable portrayal of adolescence that’s also a gratifyingly detailed depiction of life in a majority Asian California suburb. And as Chris’s mom, a woman left to hold the household together while her husband works in Taiwan and a thwarted artist trying to keep her dreams of painting alive, Joan Chen gives one of the year’s most lovely performances. —Alison Willmore

➼ Read our full review of Dìdi.

Oddity

Anyone who has seen the 2020 horror film Caveat knows that director Damian McCarthy has a thing for creepy dolls. The one in his new feature, Oddity, is so outrageously disturbing — a life-size wooden mannequin with a face carved in a perpetual scream — that the sight of it is actually kind of funny. Which is by design: Oddity is as ready to make a dark joke as it is to make you jump. This chiller’s intricate construction mirrors that of its restored Irish country-house setting, weaving together a murder, revenge, a psychic sibling, a mental institution, and of course that doll, and doing so with such skill and arresting imagery that the result is as satisfying as it is scary.

Last Summer

No director is better suited to making an uneasy movie about an older woman and a younger man than Catherine Breillat, France’s reigning provocateuse, who with Last Summer makes a triumphant return to filmmaking after a decadelong break. Léa Drucker brings a fascinating flintiness to her character, Anne, a lawyer whose work representing young victims of sexual abuse doesn’t stop her from falling into bed with her 17-year-old stepson, Théo (Samuel Kircher). Anne and Théo come together in the dreamlike bubble of summer, but the film gets more interesting when the real world intrudes on their idyll and Anne proves that, in order to protect herself, she’s capable of wielding the same language used to discredit the victims she represents. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of Last Summer.

Janet Planet

Annie Baker’s wondrously delicate directorial debut manages to be equal parts mysterious and relatable — a portrayal of restless adulthood as seen through the eyes of a girl on the cusp of adolescence. As Lacy, who spends the summer adrift at home after finagling a way to come back from camp early, Zoe Ziegler is an achingly accurate 11-year-old whose anxieties about the future are balanced by a beyond-her-years solemnity. But it’s Julianne Nicholson who gives a career-best performance as Lacy’s aging hippie mother, Janet, whose love for her daughter doesn’t eliminate her need to keep looking outward for meaning — a quest that leads to a string of lovers and friends coming through the western Massachusetts cabin she and Lacy share, each visitor shedding new light on the relationship between mother and daughter. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of Janet Planet and interview with director Annie Baker.

Thelma

Writer-director Josh Margolin’s film follows a 94-year-old woman who goes on a quest to locate the crooks who scammed her out of $10,000. Somehow, it manages to be so charming and heartfelt that the laughs never feel lazy, cheap, or cruel. It’s anchored by a delightful performance from June Squibb, a marvelous actor who has never gotten a lead role like this; she turns what is otherwise a pretty simple, cute setup into something far more profound. The protagonist’s quest to find the people who did this to her becomes about more than righting a wrong or getting her money back; it’s a way to prove to everyone (and herself) that she still has agency in her life. That doesn’t stop Margolin from riffing on spy movies and action flicks. One of Thelma’s inspirations is the spectacle of Tom Cruise sprinting across the rooftops of London in Mission: Impossible — Fallout. For her, he becomes a symbol of persistence and resilience in one’s advancing years, and for us, she becomes the same. There’s a compelling universality to the film: As the world spins ever forward, we all wind up out of touch with it soon enough. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Thelma and interview with star June Squibb.

Robot Dreams

Pablo Berger’s animated adaptation of Sara Varon’s 2007 book, the story of a dog and its pet robot in mid-1980s New York, was nominated for the Best Animated Feature Oscar earlier this year. But its hand-drawn, fablelike style, along with its entrancing and melancholy beauty, feels old-fashioned in a contemporary animation world largely defined by clutter and smarm. With zero dialogue, the film follows a lonely dog (known simply as Dog) who purchases a robot companion by mail. Dog assembles Robot, and the two of them proceed to spend a wonderful summer in the overcrowded, sweaty city. But then they’re suddenly separated, and their lives diverge. The always awkward Dog finds another companion while Robot has encounters with the rest of the world that are sometimes dreams, sometimes real. Though the story seems to take place over the course of one year, we see New York change around these characters as well. Watching Robot Dreams, we find ourselves reflecting on how our own lives have changed as we’ve grown: the friends we’ve left behind but haven’t forgotten, the cities that have transformed around us, the wisdom we’ve accrued, and all the ways in which we’re still slightly damaged from all that living. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Robot Dreams.

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

A prequel, a revenge tale, and even something of a bildungsroman, George Miller’s prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road follows the travails of the young Furiosa (played as a child by Alyla Browne, an adult by Anya Taylor-Joy) as she’s kidnapped by a motorcycle warlord named Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) and later traded off to Immortan Joe (the villain of Fury Road, here played by Lachy Hulme, in slightly younger, less pustule-filled form). Until now, the characters in the Mad Max films — yes, even the children — have arrived mostly fully formed, their minds and attitudes shaped by this dead world. Here, however, we watch a bright, young innocent lose everything that has ever meant anything to her, and her heart hardens. A pall of hopelessness hangs over the movie as we absorb the lessons of the wasteland along with our heroine. But the film is also thrilling in its own right. Action sequences charge forward and build and build, casually leaving all manner of bodies in their wake. The director also indulges his fondness for yarn-spinning, as he did in his previous film, the masterful Three Thousand Years of Longing (2022). It might not be a huge hit, but it’s nice to know that, after all these years, George Miller seems determined to stay true to his mad self. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, close look at the ending, chat with actor Tom Burke, and analysis of the Dementus’s cape.

Kidnapped

A number of filmmakers, including Steven Spielberg, have over the years attempted to adapt the remarkable true story of Edgardo Mortara, a young Jewish boy in Bologna who was taken from his family by papal authorities in the mid-19th century and raised as a Catholic. But it’s perhaps appropriate that the film was finally made by the legendary Italian director Marco Bellocchio, a man who has spent his entire career questioning the power of social institutions. Bellocchio is also a master of depicting the way madness functions in families as both an external and internal force. In the sweeping, melodramatic Kidnapped, he shows not just what happened to Edgar, but also the toll it took on his family. It’s a multicharacter saga that is at once thoroughly entertaining and thoroughly terrifying. —B.E.

I Saw the TV Glow

Haunting, unsettling, and so emotionally raw it feels like an open wound, Jane Schoenbrun’s film is an exploration of dysphoria, suburban isolation, and the imperfect refuge that is fandom. It’s easy to see traces of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Twin Peaks in The Pink Opaque, the dreamy supernatural drama that outcasts Owen (Justice Smith) and Maddy (Brigette Lundy-Paine) fixate on and bond over in high school. But while the show’s mythology seeps into their lives and serves as a metaphor Owen steadfastly refuses to acknowledge, the most compelling moment is the one when, a little older, Owen revisits the source of his obsession and finds that it’s nowhere near as compelling as it was in his memory. Pop culture can serve as a life raft and a refuge, but Schoenbrun’s film makes it achingly clear that Owen has to take the steps necessary to save himself in the real world. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of I Saw the TV Glow, interview with filmmaker Jane Schoenbrun, interview with Caroline Polachek about her song for the soundtrack.

Gasoline Rainbow

The latest movie from the Ross brothers is another freewheeling creation inhabiting a limbo between fiction and non, where first-time cast members play characters inspired by — but not confined to — their own lives, improvising scenes within the boundaries of a scripted scenario. In Gasoline Rainbow, the story takes the form of a road trip to the coast embarked on by a group of five longtime friends fresh out of high school, though the journey is less about the destination than it is the picaresque adventures the group experiences along the way, as the kids meet rail-hopping crust punks, nautically-inclined skateboarders, and Lord of the Rings-loving metalheads. It’s ragged and exhilarating, like taking a hit right off the feeling of being 18 and sure your true self is out there, waiting to be discovered. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of Gasoline Rainbow.

Evil Does Not Exist

The quietly wandering, elliptical quality of the early scenes in Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist might feel like a departure from the Drive My Car director’s recent and best-known work. We spend time with widower Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), who lives with his daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) and makes a living doing odd jobs in and around the village of Mizubiki, chopping firewood, harvesting plants, collecting water from the springs for the local ramen joint. The peaceful life of this village is interrupted with the arrival of two representatives from a talent agency that’s planning to open a “glamping” business nearby. In the film’s most bravura scene, a presentation to a group of locals devolves into an extended confrontation when the villagers begin to ask questions about a variety of concerns, most notably the placement of the site’s new septic tank, which is too small for the number of expected customers and also upstream from the town’s fresh-water source. Evil Does Not Exist rings unnervingly true in its particulars, from the bizarre bedfellows created by modern capitalism to the quiet contempt with which city folk treat poorer villagers. But Hamaguchi also doesn’t give us obvious villains, instead portraying different people from different worlds, each trying to survive in their own way. Even so, in its own discreet, modest way, the film leaves us with a haunting sense of a personal and ecological apocalypse. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Evil Does Not Exist and dispatch from the Venice Film Festival.

Alam

The conversations around Palestine and Israel often don’t leave much room for nuance, but Firaz Khoury’s moving coming-of-age film offers a corrective. Not everyone realizes that there are Palestinians in Israel, living in Palestinian neighborhoods, going to schools with Palestinian teachers — but they’re taught Israeli history, seen from Israel’s perspective, all under an Israeli flag (alam is an Arabic word for banner). So they learn about Israel’s battle for independence, even though for them it’s known as the Nakba — the “catastrophe,” in which their families were displaced in 1948. In Alam, a group of middle-class students wrestles with romance, authority, and political awakening in the days leading up to Israel’s Independence Day. These are kids with means and prospects, with families and teachers who want them to keep their hands clean. To them, the political (and physical) battles being waged over their homeland sometimes seem abstract, and yet they can’t help but look for ways to be involved. This is a marvelous, mesmerizing film that offers no easy answers. —B.E.

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed

Joanna Arnow’s feature directing debut is an unclassifiable deadpan comedy about a Brooklyn woman, Ann (played by Arnow herself), whose entire life seems to revolve around humiliation: She’s in a sub-dom relationship with an older man whose reluctant, disaffected approach to her needs might be part of their whole thing; she endures constant awkward conversations with her parents (played by the director’s own parents); she’s completely ignored at work even when she’s being given an award. There’s a surreal quality to the film, and yet it all feels so true. Arnow has captured something about the authentic and mortifying absurdity of modern life — and she’s done it in a thoroughly entertaining way. Her filmmaking style is episodic, but not in the exhausting, indulgent style of so many other plotless dramedies: Her vignettes vary from extended sequences to comically brief snippets, giving the picture a unique and irresistible cadence. —B.E.

Civil War

What makes Alex Garland’s controversial new film so diabolically clever is the way that it both revels in and abhors our fascination with the idea of America as a battlefield. The film is set in what appears to be the present, but in this version of the present a combination of strongman tactics and secessionist movements have fractured the United States into multiple armed, politically unspecified factions. Smoke rises from cities; the highways are filled with walls of wrecked cars; suicide bombers dive into a crowd lined up for water rations; death squads, snipers, and mass graves dot the countryside. How we got here, or what these people are fighting over, is mostly meaningless to the journalists covering this war, who gather in hotel bars, get drunk, and loudly yuk it up with the jacked-up bonhomie we might recognize from movies set in foreign lands like The Killing Fields, Under Fire, and Salvador. They’re mostly numb to the horrors they’re chronicling. The movie’s lack of a political point of view has received some understandable criticism, but the conceit here is to depict Americans acting the way we’ve seen people act in other international conflicts, be it Vietnam or Lebanon or the former Yugoslavia or Iraq or Gaza or … well, the list goes on. It doesn’t want to make us feel so much as it wants us to ask why we don’t feel anything. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Civil War, interview with director Alex Garland, and essay on the movie’s final shot.

In Flames

Could we call In Flames, Pakistan’s submission for last year’s Best International Film Oscar, a horror movie? How could we not? It looks at the life of a young Karachi woman whose world is upended after the death of her father: Men stare at her, attack her, obsess over her, ignore her. The prying eyes of a patriarchal society see her as both victim and prey. A brief, seemingly promising relationship ends in tragedy. She’s pursued by haunting visions as she begins to lose the line between reality and illusion. Director Zarrar Khan depicts both supernatural shocks and real-life terrors with the same jump-scare-laced bravado but does so without ever shortchanging the very real drama at the film’s heart. —B.E.

The Beast

Bertrand Bonello’s sci-fi epic is Henry James by way of David Lynch, a beguiling, slippery creation that spans three time periods and settings, and that manages to constantly surprise and unsettle. As Gabrielle, Léa Seydoux is a tragic costume-drama heroine, a stalkee in a horror film, and a frustrated seeker in an aloof futurescape, and she manages to create a sense of continuity over these very different lives, into which Louis (George MacKay) inevitably appears. The Beast is wistful, scary, and unsettling, and more than anything, it’s a big swing — a movie about being afraid of vulnerability that is itself fearless. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of The Beast.

The First Omen

Directed by Arkasha Stevenson, this prequel to 1976’s The Omen is another modern horror movie that speaks to our current moment even as it tells a fantastical story rooted in the past. In this case, the year is 1971, and young novitiate Margaret Daino (Nell Tiger Free) has just arrived in a turbulent Rome to work at an orphanage. She becomes intrigued by the odd, introverted Carlita Skianna (Nicole Sorace), one of the orphans. She sees something of herself in the girl and tries to forge a bond with her. Then a rogue priest warns her that Carlita might have been bred by the church specifically to give birth to the Anti-Christ — this is, after all, an Omen movie — and our protagonist becomes determined to save the girl. The film will surely leave you with more questions than it answers, but like the best studio horror directors, Stevenson understands that we’re not here for logic. The movie is soaked in style and mood with images that are both textured and shocking and that tap into tantalizingly visceral fears. If horror is all about loss of control, about feelings of helplessness conjured in the audience to reflect the helplessness of the characters, then this is a true horror film. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of The First Omen.

La Chimera

Alice Rohrwacher’s film follows Arthur Harrison (Josh O’Connor), a strange man with a strange gift for robbing graves, finding and lifting the antique knickknacks the ancient Etruscans of central Italy used to bury with their dead. A former archeologist, he seems haunted by his own exploits, and this occasionally rambling, often gorgeous film’s queasy dream logic suggests that we’re watching a man halfway between this world and the next, struggling to find his place. Rohrwacher, one of Italy’s foremost filmmakers, makes earthy movies with a dash of what we might call magical realism. The performances are naturalistic, the location shooting authentic and ground level, but the stories often hover on the edge of fantasy. The director fills the picture with folk ballads, naif art, playful asides to the camera, and bursts of sped-up slapstick, giving it all the quality of a ramshackle operetta. But O’Connor’s concave, melancholy demeanor undercuts the picture’s levity, likely by design: The more the film goes on, and the more fanciful it becomes, the more Arthur seems unable to reconcile himself to the world around him. He’s a sad, walking embodiment of the notion that those who spend their time worrying about the next life will never feel peace in this one. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of La Chimera.

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus

A few months before he died in March 2023, Ryuichi Sakamoto recorded what he suspected might be his final solo concert. It had been created across a few days out of prerecorded segments that were then assembled and streamed around the world. An expanded version of that concert now exists as a feature film directed by the late musician’s son, Neo Sora, and it’s a moving, spare, and self-reflective work. Sakamoto was a savvy and thoughtful performer, always aware of his audience and in playful conversation with them. Now, as he communes with his music, we feel like we may be intruding on a private requiem. He doesn’t seem particularly frail during this performance; the fragility lies in the music, in the vulnerability with which he plays it, and in the austere cinematic presentation. The shimmering black-and-white photography and elegant camera moves heighten the intimacy of the performance. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus.

Dune: Part Two

If the first Dune was Timothée Chalamet’s movie, the second belongs to Zendaya, and it’s better and more emotionally accessible for it. Denis Villeneuve’s Frank Herbert adaptation continues to be a spectacular and genuinely alien epic about genetically engineered messiah figures, space witches, massive sandworms, and BDSM-inflected goth fascist planets. But it’s Zendaya’s character, the Fremen warrior Chani, who provides the film’s heart, as a fierce-hearted rebel who’s won over by Chalamet’s Paul despite knowing better, and despite being aware that he’s saying all the right things to win her community to his side for what may be his own purposes. Dune: Part Two has incredible sweep, but it also manages to have recognizable human drama, and that comes entirely from Chani’s perspective as the representative of a people whose own desires are forever subsumed by the machinations of much larger powers. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of Dune: Part Two, behind-the-scenes look with cinematographer Greig Fraser, and analysis of the ending.

Shayda

Noora Niasari’s debut is based on her own childhood experiences, which is evident from the tangibility of its details, but also from the poignant sense that it’s a film about revisiting turbulent young memories with the distance and knowledge of an adult. Holy Spider’s Zar Amir Ebrahimi gives an astounding performance as the title character, an Iranian immigrant in Australia who’s fled an abusive marriage and brought along the young daughter, Mona (Selina Zahednia), that she’s terrified will be taken from her. Shayda deftly lays out the dynamics of the womens’ shelter, and of the local Iranian enclave, pitching its story of escape as a kind of intimate thriller in which Shayda must try to create a sense of normalcy and safety for her child while never being able to let her own guard down. —A.W.

Io Capitano

The Italian director Matteo Garrone likes to fuse the topical with the fanciful, and in this modern-day tale of the refugee crisis, he’s made one of his more shattering films. It follows the journey of two Senegalese cousins, Seydou (Seydou Sarr) and Moussa (Moustapha Fall), who set off for Europe and find themselves confronted along the way with a variety of monstrous incidents, which feel at times like terrifying images out of an old storybook. Garrone mixes magical realism, epic sweep, and gruesome horror in a story that’s been built out of the experiences of real people who’ve made this journey. But he’s not interested in alarmism. His protagonists aren’t desperate to flee any kind of abject poverty or strife — they simply want to travel to Europe, the same way that First World youths have sought to see the world for decades, even centuries. That’s maybe the most novel (and heartbreaking) aspect of Io Capitano. It rejects the idea of its heroes as solely victims, instead placing them in a grander, nobler tradition of exploration and curiosity. In doing so, it asks an implicit, and pointed, question: Why don’t we in “the West” also see them in this light?

The Promised Land

Mads Mikkelsen is a phenomenally skilled actor, but he’s also clearly the kind of performer who understands the value of a good, cold, hard stare. This makes him uniquely well-suited for the role of Captain Ludvig Kahlen, an impoverished, stoic Danish war veteran who sets out in the mid-18th century to try and tame the Jutland Heath, a huge and forbidding area where no crop can grow and where lawlessness reigns. The Danish title of the film, Bastarden, translates as “the bastard,” and could be both a literal and spiritual description of Kahlen. He was born to an unwed servant, and he is a tough, at times heartless taskmaster. As he learns that he has to learn to rely on others in order to survive, Kahlen also finds himself at odds with a local landowner, a preening and sadistic aristocrat named Frederik de Schinkel. And so, The Promised Land transforms from a stately and lyrical tale of rural survival to something more primal and intense; think Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven crossed with Michael Caton-Jones’s Rob Roy, only with more scenes of people being boiled alive. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of The Promised Land.

Pictures of Ghosts

This terrifically bittersweet documentary from Bacurau’s Kleber Mendonça Filho is part memoir, part history of the director’s hometown of Recife, and part meditation on the nature of photography that outlasts the subjects it has captured. But more than anything, it’s a tribute to a life shaped by cinema that manages to avoid the syrupy sentimentality of so many other movies about movies. Filho starts his film in the childhood apartment where he shot so much of his work, and then guides it outward, to the city’s once-grand downtown, studded with cinematic palaces that have mostly been repurposed into other businesses. In doing so, he gracefully reflects on the faded glories of his favored medium. —A.W.

➼ Read our full review of Pictures of Ghosts.

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

Phạm Thiên Ân’s first feature can be elliptical to a fault in the way it chooses to unfold its story of a drifting young man named Thiện (Lê Phong Vũ) who, after the death of his sister-in-law, inherits custody of his nephew and embarks on a journey to find his brother, the child’s father. But the virtuosity of its filmmaking is remarkable, and some of the shots that Ân composed (with the help of his cinematographer, Đinh Duy Hưng) have lingered with me like persistent afterimages. In particular, there’s the sequence that starts the film, in which the camera drifts from a nighttime soccer game in Saigon, past street vendors and spectators and over to a bustling outdoor cafe where three men are talking about faith over beers until they’re interrupted by an off-screen collision. It’s impressive in its complexity and utterly haunting in its execution, as if it contains the whole world before its focus narrows in on one particular figure. —A.W.

Frida

There have been many movies about Frida Kahlo over the years, but none have given us such a sense of the artist as an actual living, breathing person as Carla Gutiérrez’s innovative new documentary. Gutiérrez, an award-winning editor, has built the movie entirely out of archival material, using Kahlo’s own words and pictures to present her life as seen through her own eyes. Thus, we hear Frida’s own achingly confessional words (spoken by Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero) as she narrates her childhood, growing up with a deeply religious mother and an atheist father; her vivacious teen years as a hip young medical student, adored by many; her lengthy, turbulent marriage to the lecherous, revolutionary muralist Diego Rivera, who overshadowed her in her time; as well as her own passionate affairs with both men and women. The director has also taken Kahlo’s drawings and paintings, including some of the most immortal ones, and animated them so that the images now shift before our eyes to reflect her emotional transformations, with pictures often mutating into one another. It’s an inspired path into the work of an artist who often painted her own visage in visually striking arrangements. By the time the movie is over, we feel, perhaps for the first time, like we’ve gotten to know this legendary, almost mythical figure. —B.E.

➼ Read our full review of Frida.