This interview was originally published on March 13, 2023. We are republishing it following the news of Jaffee’s death on April 10, 2023.

A shorter version of this interview was originally published in Mike Sacks’s 2009 book, And Here’s the Kicker: Conversations With 21 Top Humor Writers on Their Craft.

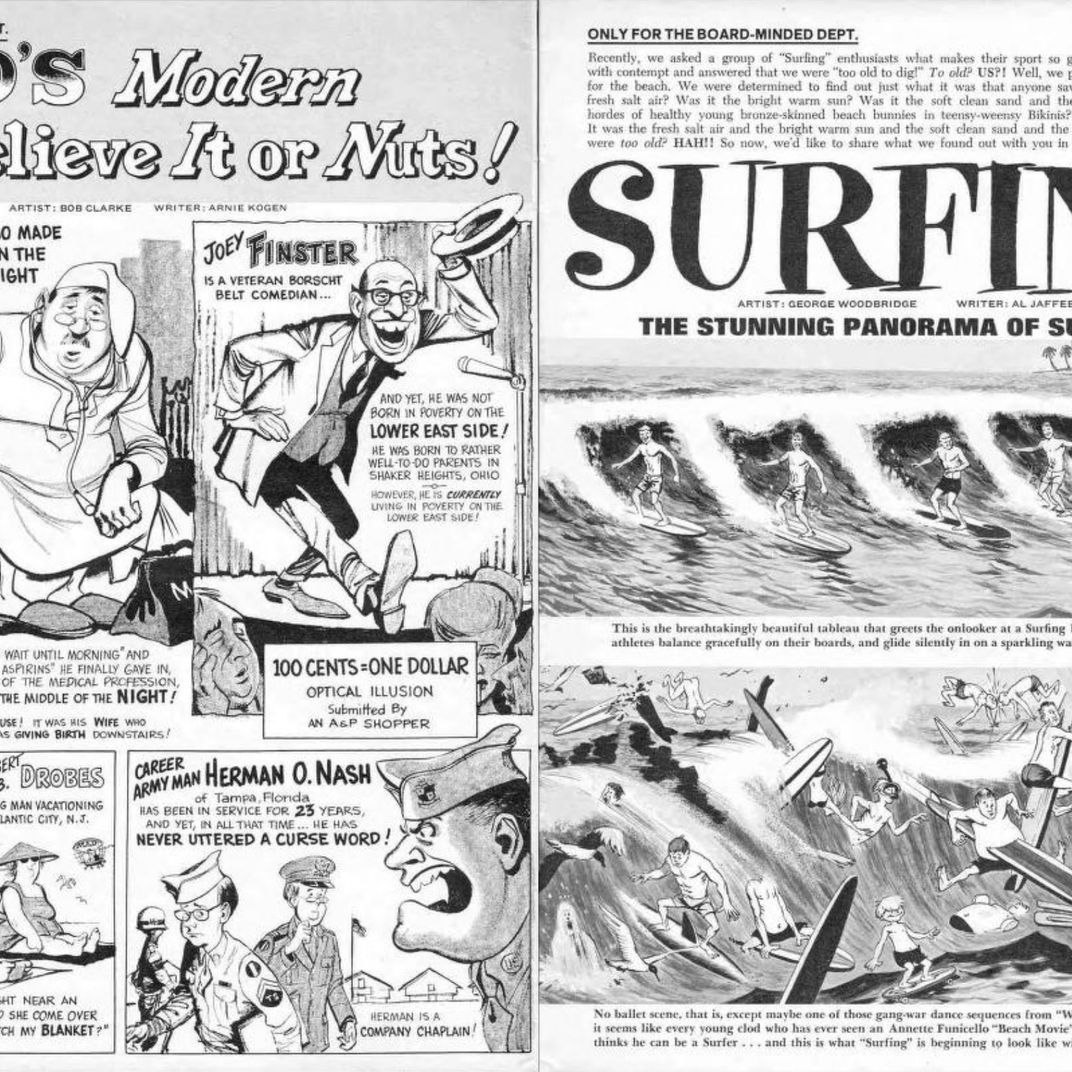

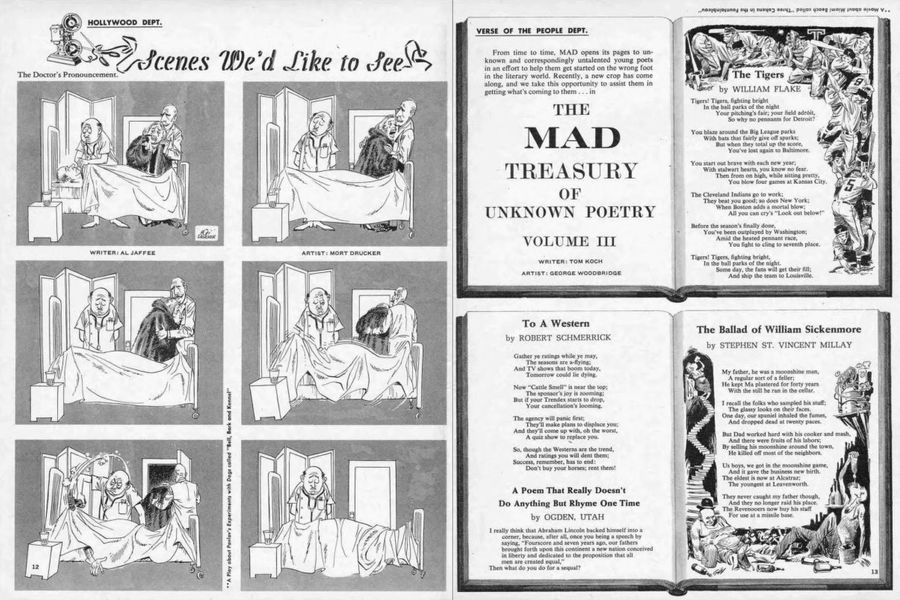

In 2009, I put out a book of interviews I conducted with my favorite comedy writers. It was called And Here’s the Kicker. The writers I interviewed included David Sedaris, Paul Feig, Bob Odenkirk, Allison Silverman, Jack Handey, and writer and illustrator Al Jaffee, who was a spry 87 when I spoke with him in 2008 over the phone for over two hours. Although Jaffee created some of MAD’s most memorable humor since the magazine’s inception in 1952 — from “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” to the Vietnam-era, antiwar cartoon “Hawks & Doves”— his legacy will forever be tied to the brilliance of the MAD “Fold-in.”

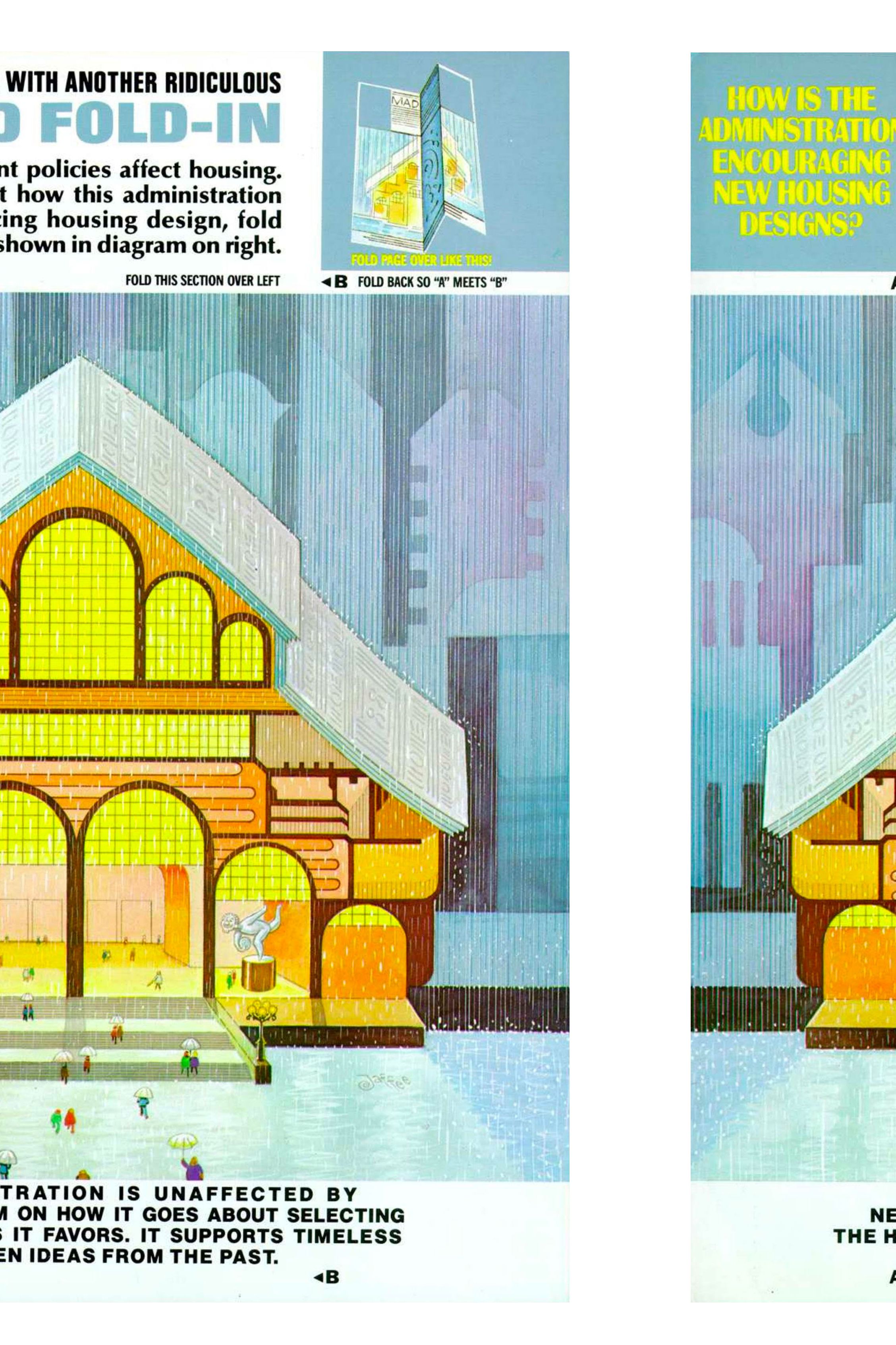

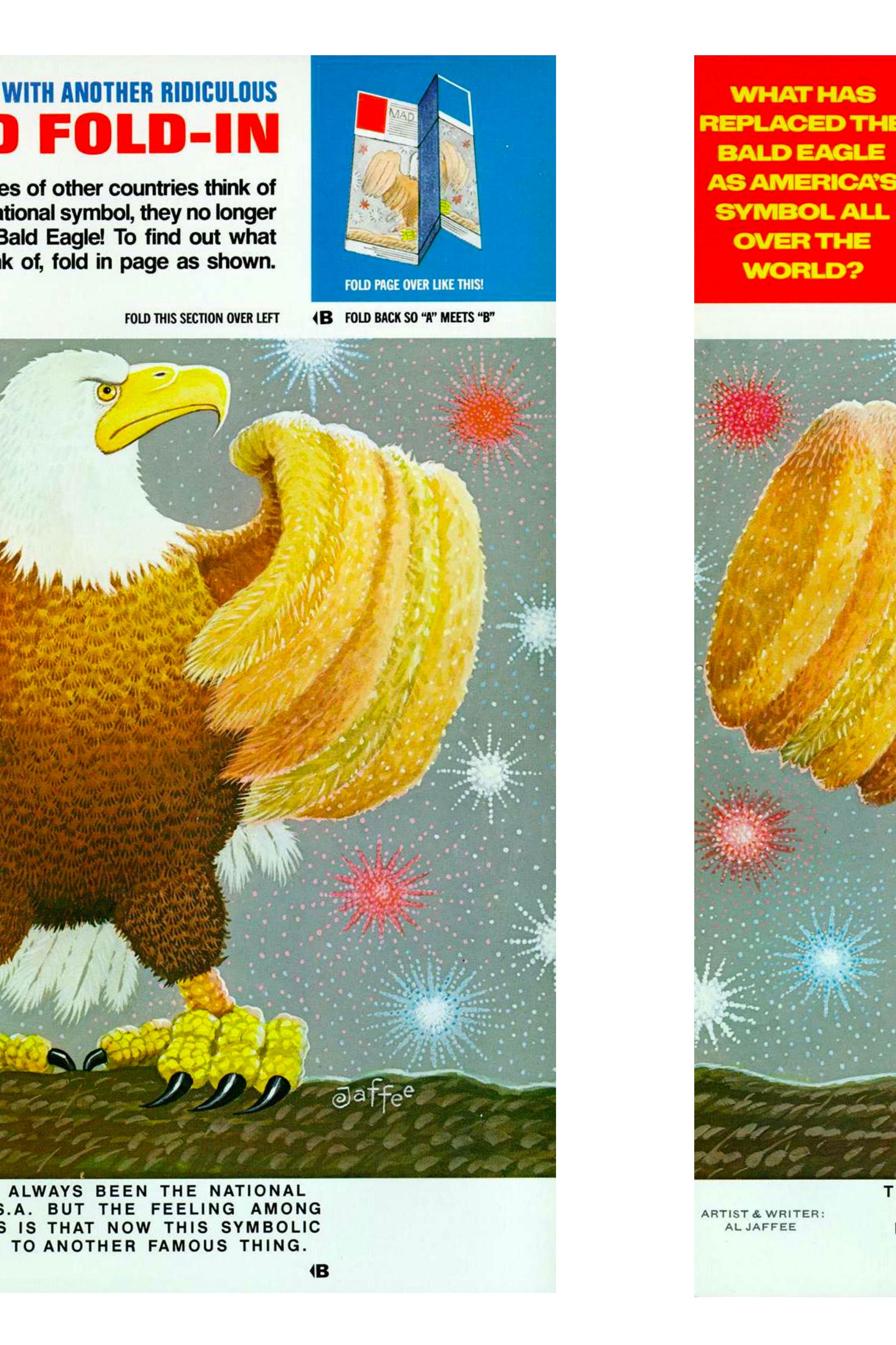

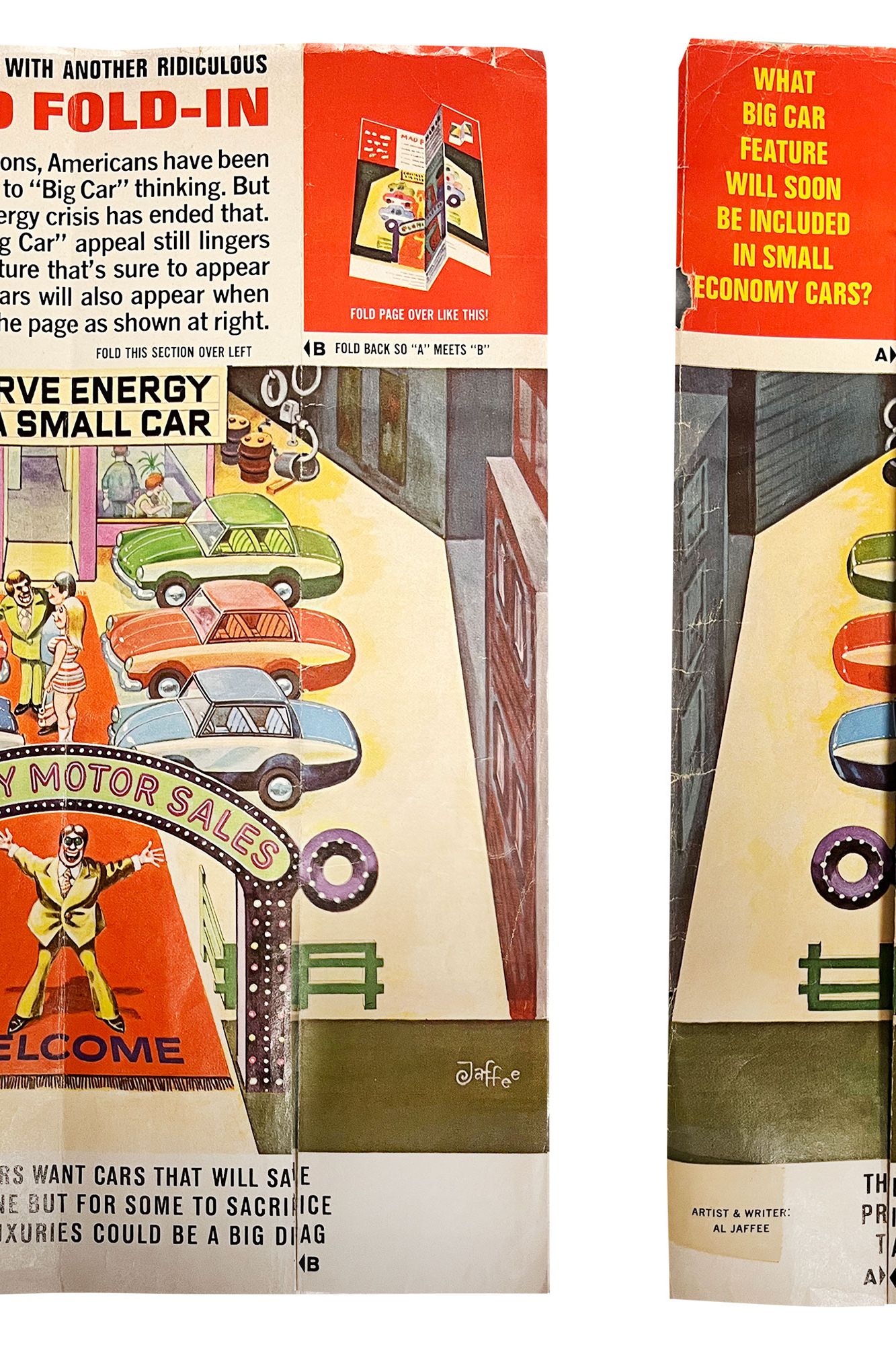

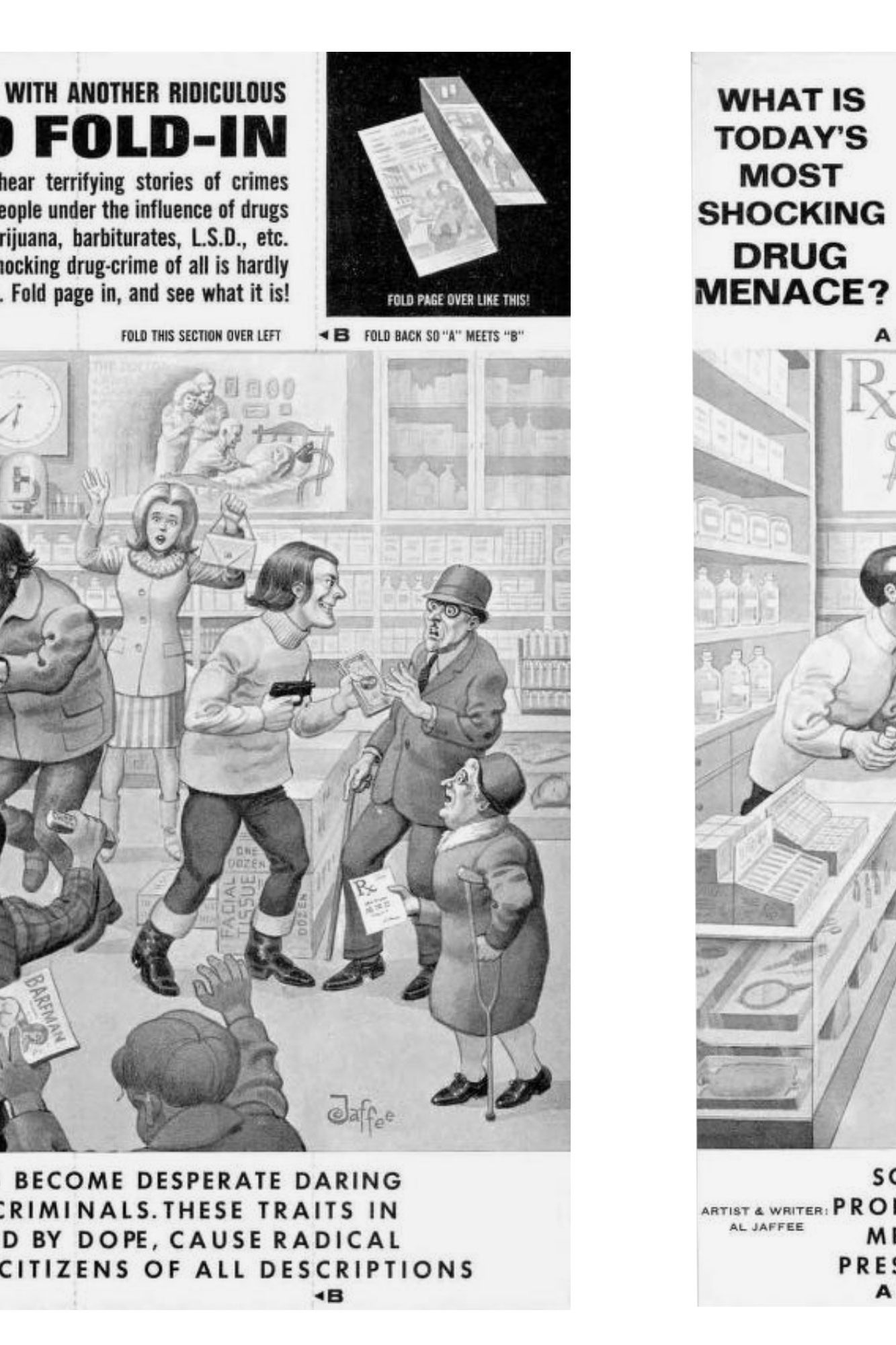

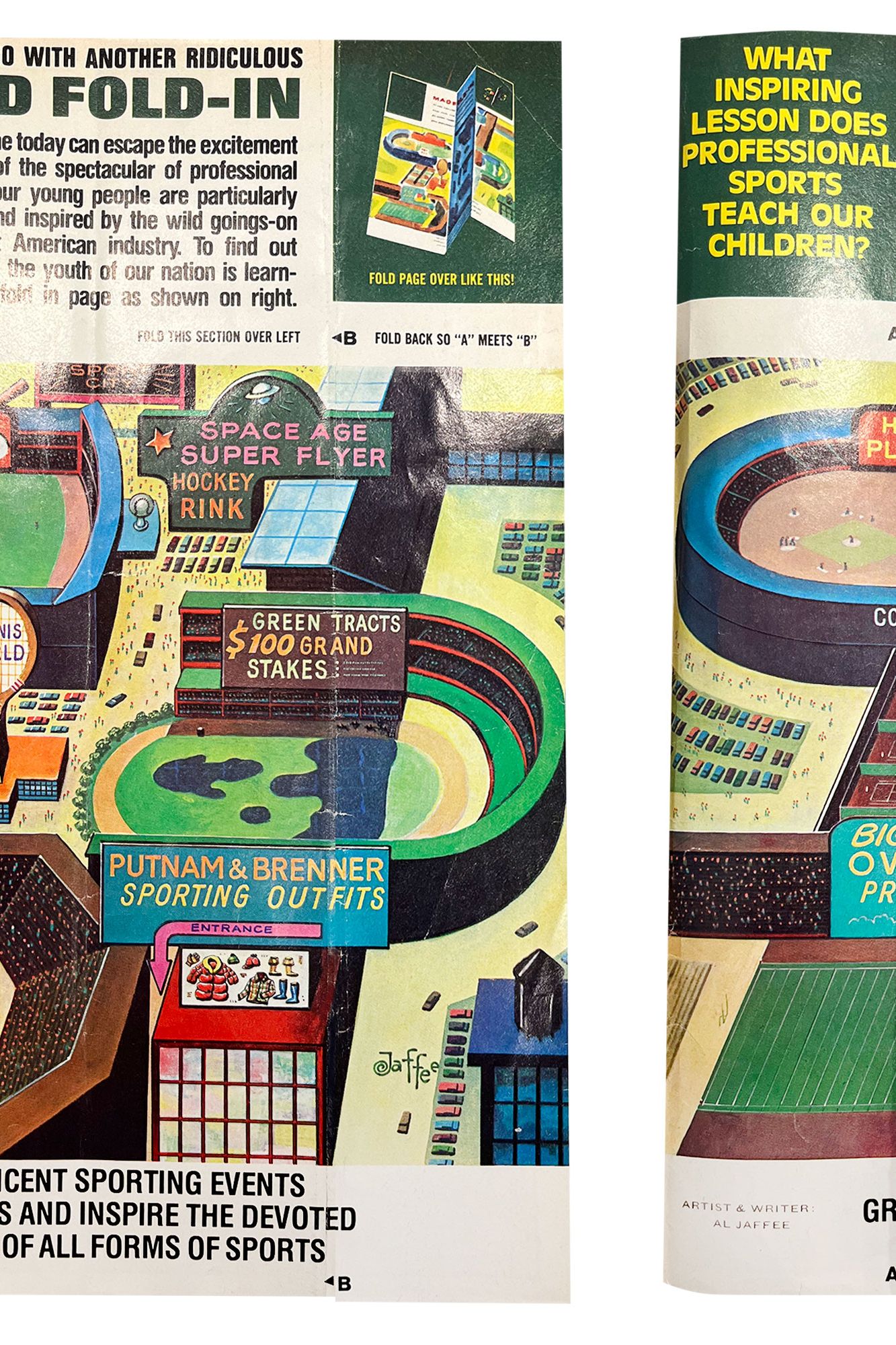

Originally intended as a onetime parody of Playboy’s foldouts, Jaffee’s recurring feature, which appeared in MAD from 1964 until its demise in 2019, became almost as recognized and imitated as Alfred E. Neuman’s gap-toothed grin. Located on the magazine’s inside back cover, it featured a drawing that, when folded vertically and inward, revealed a hidden picture and a surprise joke. But what made the “Fold-in” so brilliant wasn’t merely the concept. Deceptively simple and seemingly innocuous, it was a cache of subversive satire. Judging from some of the references over the years, Jaffee had always trusted the intelligence of his audience, even when they were no more than pre- or just-pubescent kids looking for a quick laugh before bedtime or during math class. How else to explain the very adult punch lines like “Soaring Profits in Medical Prescriptions” or “Hiding the Homeless Problem”? Or the gag in which an American bald eagle transforms into another, perhaps even more popular cultural icon: the Big Mac?

One can easily imagine generations of young humor writers, including notorious MAD fans Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, reading one of Jaffee’s “Fold-in”s for the first time and realizing what could be done with the written word and slight tweaking of an image. After all, Colbert celebrated Jaffee’s 85th birthday on his Comedy Central show, The Colbert Report, in 2006 by creating a “Fold-in” vanilla birthday cake. It included the message: “AL, YOU HAVE REPEATEDLY SHOWN ARTISTRY & CARE OF GREAT CREDIT TO YOUR FIELD. LOVE, STEPHEN COLBERT.” But when the cake’s center was removed, it read, “AL, YOU ARE OLD.”

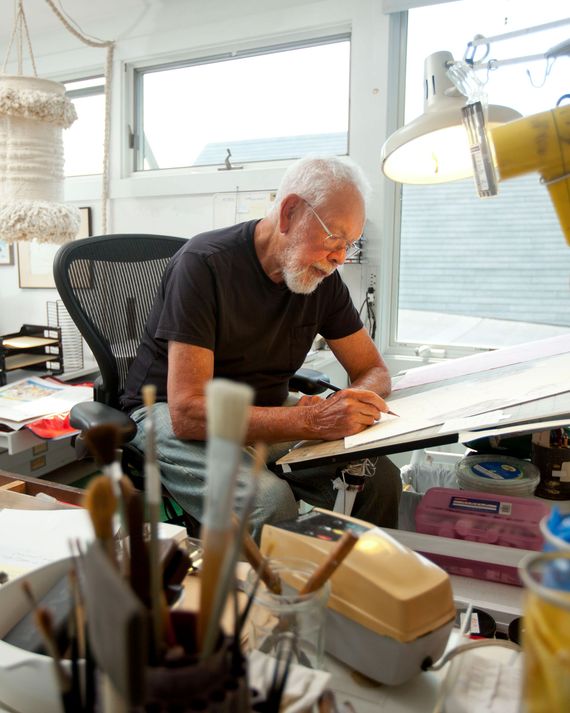

Today, Jaffee turns 102, and to commemorate, I’m publishing for the first time online an extended version of the interview I conducted with him in 2008, before it was cut down for inclusion in my book. Jaffee is a

link to another time, another world, when humor magazine writers and illustrators were stars and sometimes even household names. More importantly, Al is a genius and a mensch and deserves to be honored on this most celebratory of days.

For someone who’s spent more than 50 years contributing to such an American comedic institution, you spent a fair amount of your childhood in a country not necessarily known for its humor.

That’s right. I spent six years in Lithuania, from the age of 6 to 12. At that time, most of the Lithuanian Jews lived in ghettos. I lived in one, too, in a town called Zarasai.

But you weren’t born in Lithuania?

No, I was born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1921. But both of my parents were from Lithuania. My mother was very religious, and she wanted to go back to a place where she felt comfortable. She moved back, and brought me and my three brothers with her. This was in 1927.

How did those six years in Lithuania affect your comic sensibility?

My father remained in America through those six years, and I made him promise to send me American comic strips. Every few months or so, my brothers and I would receive a package of rolled-up Sunday color comics and daily comics. We would just sit there and read them for days and days. My brother Harry, who was also artistic, would take these Sunday comic pages, and we’d cut them up and turn them into little books. We would provide our own dialogue, maybe with a Lithuanian joke or two.

Most of the comics we received were humorous. Some were adventurous, in the “Little Orphan Annie” mold. There was no TV or radio, so that was pretty much it for us. But I would see humor in everything, even in the religious practices, which didn’t quite register with me.

I found religion sort of funny. There was something that just didn’t make sense about not being able to play ball or not being able to walk too far on the Sabbath. These very strict religious prohibitions against any kind of enjoyment just struck me as being very old-fashioned and strange. Maybe I was bringing my Savannah influence with me; I don’t know. I was sort of straddling these two cultures: the New World and the Old World.

Beyond “Little Orphan Annie,” what were some of your other favorite comic strips then?

I loved “Wash Tubbs,” by Roy Crane. Oh, God, that was one of my favorites. Crane created these comic strips about a mythical kingdom somewhere in Europe, and I could identify with those things. The mythical kingdom that Crane created was closer to the village I was living in at the time than anything else. That resonated pretty well with me. In addition, Crane was an absolute master cartoonist. His work was realistic, but not super-realistic.

How so?

The characters did not look realistic the way “Superman” characters looked. They looked like cartoon characters, but everything was in perfect proportion. And all of the elements, whether it was a train or an automobile, it all looked very real — but in a sort of animated way.

Did you adopt this style for yourself later in your career?

I did. I don’t consider myself a very good artist. I never have. I really don’t know anatomy. I can’t draw a specific automobile or a specific train out of my imagination, but I think I can do a pretty good job of imagining an automobile or imagining a train. So I can’t compare myself to Roy Crane, because he was head and shoulders above me, but I do have an affinity for the kind of things that he did — when you don’t have to go and get a reference book to draw a Chevrolet and reproduce it in perfect detail.

People might be surprised when I refer to myself as not such a great artist, but I only try to meet the needs of the story. Without having a story to tell, my art has no meaning. Rembrandt may have been able to achieve meaning without a story, but I can’t.

Then again, if you put a Rembrandt-style artist into MAD, the reader would focus so much on the artist’s style that it would overwhelm the comedy and the writing.

It’s sort of complicated to figure this out, but I really feel that the idea has to precede the artwork, and if the idea says this is a fantasy … well, then there’s no point in going out and getting reference materials. You just draw what’s in your head.

How prevalent was antisemitism in Lithuania when you lived there?

There was a great deal of antisemitism, which was a source of humor for me — dark humor. I’d sit around with my friends in their houses and listen to the grown-ups talk about the latest prohibition against Jewish commerce, or whatever. They would take it seriously, but they would also ridicule and make fun of it.

A lot of the children’s jokes that went around at that time had to do with restrictions against the Jews that were set by the government. Between the restrictions coming from our own religious community and those coming from the antisemitic government, you were caught in such a ridiculous situation. The only thing you could do was laugh at it, make fun of it.

And yet this outlet of humor could have been quite dangerous for a Jewish kid. Humor can cut deep.

Well, we would do this in the privacy of our own homes. My mother would mimic Gentiles in my grandfather’s house and everyone would roar. It was similar to what cartoonists would do in the early years of cartooning: making a joke about a pompous businessman by having his hat knocked off by a regular shmoe throwing a snowball. In the same way, by imitating some official from the post office or the town hall, you could knock someone down a peg or two. It became a kind of bittersweet laugh.

Beyond humor, I suppose there’s another response, which would have been to become angry.

Well, I was angry at my mother, because she was very strict and she spent a lot of time with her religious activities, leaving both my brothers and me feeling neglected. I just don’t believe in fantasies. And it seemed to me that 90 percent of the religious stuff that was being said was fantasy.

It’s like Santa Claus: There was no Santa Claus, and there was no magical rabbi, and there was no magical anything. All of it was illusion. But humor was an outlet for me, an escape. It was an escape from what I saw as idiotic behavior by everyone.

I don’t think humor is just here to tickle people. Humor has much deeper roots than that.

Why did you eventually return to the States?

My father brought us back when Hitler came to power. This was in 1933. My mother chose to remain behind. She said that she would join us later, but she never did. She died around 1939, although I’ve never found out how. There are no records. The Red Cross thought it might have been caused by the local partisans eager to help the Nazis after they invaded Lithuania.

Did you speak Yiddish when you returned?

I did, yes.

When you look at the early issues of MAD, there’s a lot of Yiddish used.

Harvey Kurtzman, the founding editor of MAD, lived in Brooklyn, and his parents were born in Russia and spoke Yiddish. If you were living in New York, or the Jewish section of the Bronx, which is where we moved after I returned, you heard Yiddish everywhere. All the words that were used to make fun and to insult people were in Yiddish: “Look at that shmegegge.” When Harvey started MAD, he just got a kick out of that. He brought in a lot of Yiddish, as did some of the other writers.

The interesting thing about Yiddish is that there are no dirty words. All the dirty words have other meanings.

Really? How about schmuck?

Schmuck is a “jewel.” It comes from schmücken, which means “to decorate.”

And putz?

Putz means “penis,” but it could have come from the word farputzed, which means to get gussied up.

It’s the perfect language for a publication like MAD. The words were funny in and of themselves, and they also sounded adult and a little dirty.

There are elements in humor that have to do with sound and timing, and how the syllables are separated, but a lot of credit has to go to the person who is making it funny. The words themselves can’t always do it. For a stand-up comic, it’s the inflection and even the buildup, setting the scene. Sometimes you set the scene with just the way your eyes move.

When you’re doing humor, you use every device you can think of: funny sounds, things that seem insulting when they’re really not. A lot of stuff that’s in the English language comes from someone making a funny sound. Jerry Lewis used to make a sound like “Melvin.” Harvey adopted it for MAD. When you take an ordinary name like “Melvin” and you do it in a goofy sort of way like Jerry Lewis did, it begins to sound like a very funny, weird word.

What was it about the word “Melvin” that was funny?

There are funny sounds and there are sounds that are not funny. The word “flatulence” is funny. The word “coughing” is not funny.

You attended New York’s High School of Music & Art with seemingly half of the future MAD’s original “Gang of Idiots.” Who were some of your classmates?

Harvey Kurtzman; Al Feldstein, who took over for Harvey in 1956 and became the editor for about 30 years; John Severin, who was a brilliant illustrator; Will Elder, another brilliant illustrator. And there were others who came afterward, people I only got to know later in the comic business.

Did this school teach fine art or commercial art?

Oh, it was all fine art. In fact, I remember one day in the late ’30s when Will Elder came into school, and he had meticulously drawn all of the seven dwarfs from the movie Snow White. The teacher was not happy. I mean, she really reamed him out, because he was showing these drawings to everybody.

He’d drawn these characters from memory, from having watched the movie just once?

Yes. He had a fantastic eye and memory. He drew them perfectly, without any reference source. There were no books about the movie; it had just come out. And there was no internet, of course. He saw the movie, and he went home and just drew the characters.

So why was this teacher upset?

Cartooning was not allowed. It was looked down upon. We were there to study painting and sculpture and engraving, and we did all of them. We had very good teachers, but the head of the art department, Miss McDonald, was very strict about not introducing commercial art into the curriculum.

Looking back, I think she was right. Getting a good background in fine art is very, very helpful when you go on to do even silly cartoons.

What was your first comic-book sale? How old were you?

I was 20. I went to see Will Eisner, who was the creator of a comic strip called “The Spirit,” which was beautifully drawn and very creative. The opening splash pages were all so brilliantly conceived. In the comics field, we all admired this strip tremendously. Will was a genius. He just did beautiful work.

I had created a parody of Superman called “Inferior Man,” and I wanted to show it to Will. It seems so naïve now, but it seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

Was this the first parody of Superman? This would have been what, the early ’40s? Superman had only been around a few years at that point.

At that time, there was another character who was called Stuporman — it was published by DC Comics. I don’t know if mine was the first Superman takeoff, but it really doesn’t matter. I came up with mine independently. Since then, I’ve seen a million takeoffs, but, at that time, there weren’t many. When I brought this idea to Will, I had no idea whether I was doing something stupid or not. But Will, who was only a few years older than I was, was already very successful. He hired me on the spot to do “Inferior Man” as a filler for his comic books.

To have made a major sale at the age of 20 must have been very exciting. Not to mention a real boost to your career.

It was, certainly. But whenever I read news reports or stories about that time, or I hear people talking about it, one element that’s usually left out is the realistic atmosphere. Our families had either just come out of the Depression or were still in the Depression. No one opened the gate and said, “Depression over!” You had a lot of baggage, and some of that was trying to figure out how to become self-sustaining and not have to rely on your parents. So with the comic-book field, the buzz was, “There’s work.” You can get so much money per page. All you have to do is write and draw cartoons. I was making three times as much as my father was making as a postal worker.

You were working only on your “Inferior Man” comics?

No, I was also making extra money doing some penciling for a cartoonist who worked for Timely Comics, which later became Marvel Comics. After a while, though, I realized that I was being exploited. I was being paid eight dollars a week. So I became disillusioned and skipped the middleman and went to work directly for Timely Comics.

Stan Lee, later the creator of Spider-Man, had just become the editor at Timely. He was about 17 years old, maybe 18, and I went to see him at his office. He looked at a few of my samples, then handed me a script called Squat Car Squad and said, “Let’s see what you can do with that. Go illustrate it.” When I brought it back, he said, “I don’t have any more scripts for you to illustrate, but why don’t you keep writing and drawing this one?” So I did a lot of Squat Car Squad, which was a simple comic about two policemen. But I had a great time with it.

Did you work on any other characters at Timely?

After the war, I wrote and illustrated a teen character named Patsy Walker. I did this for about five years. I didn’t create this character — a woman by the name of Ruth Atkinson did — but I worked on it. The American public goes through cycles, and the cycle at that time was teenage humor.

The idealized version of that carefree teen life wasn’t the sort of lifestyle you and the other comic artists were leading, I take it?

That’s absolutely correct. We were coming out of an economic depression and then war. Many of us were starting to get married and have families. So things were changing. But we were living fantasy lives through our work. We were creating these worlds, in the comics, that we wished our childhoods could have been.

Did you have an advantage by being not only an artist but also a humor writer?

Yes. For a very, very gifted artist like Jack Kirby, it was very easy, because he could get five comic-book houses to battle for his services. I didn’t have that advantage. I really could not break down any doors just by showing my drawing skills. So for me and others like me, the only way you could create work for yourself was to create a script, create an idea. And then if you’re lucky, they will let you do the artwork. When I went back to MAD after working on [the knockoffs] Humbug and Trump and all of those things that failed, they hired me as a writer for many years. So being able to write humor was a big advantage for me, because I could then kind of shoehorn in my drawing ability.

You once said that you weren’t producing work at this time to be hung in museums. You were working to pay the rent.

That’s pretty much what I think all of us were doing.

But the irony is that a lot of this work is now being hung in museums.

That is ironic. It is.

Was there competition among the young comic-book artists at this time?

Oh no, there wasn’t any competition between one artist and another. A lot of people were insecure, because there’s always someone coming along who can take your assignment away from you by showing much better work. But ultimately, all you could do is do your best. And then our editor, Stan Lee, could evaluate it and decide whether he wanted to keep you doing it or give it to somebody else. But Stan was a pretty nice guy from my experience. If he felt that there was somebody that could do something better and he took a feature away from one particular artist, he would try to find something else to give that artist and keep him working. So it wasn’t cutthroat.

When did you make the move to MAD?

In 1955, three years after the magazine began. Harvey Kurtzman came to me and asked if I’d like to come and work for him. I had freelanced for MAD with a couple of pieces, and he liked my work.

Was it a big leap for you — leaving the comfort of Timely to go work for MAD?

It was. I was making a very nice living at Timely, but it just seemed like the right time. I told Stan Lee I was leaving, and then I called Harvey and said, “I’m coming with you.” And he said, “Well, actually, I’m not with MAD anymore. But don’t worry. I’ve got something in the works.” He had just left MAD for a new humor magazine published by Hugh Hefner, called Trump. This was in the mid- to late 1950s.

Harvey bridled at the fact that he had to pass all editorial decisions through Bill Gaines, who was the publisher of MAD, and that bothered him a great deal. So when Hefner came along and offered to produce a slicker version of MAD, and it would be in color, no less, it seemed like the right thing for Harvey to do. It wasn’t just a money thing for him. What he really wanted was control.

What was Trump like? It was the first of countless MAD knockoffs throughout the years.

There were only two issues produced, but it was a beautiful, sleek product. We took too long to produce it, and it was too expensive. Harvey was just too much of a perfectionist, which is what I loved about him. He made changes in my pieces that nobody else would have made. It really improved the quality of my work. As an editor, he was incredible.

There’s a group of MAD aficionados who feel that if Harvey Kurtzman had stayed at MAD, the magazine would not only have been different, but better.

And then there’s a large group who feel that if Harvey had stayed with MAD, he would have upgraded it to the point where only 15 people would buy it.

Harvey did a very interesting thing. His sense for truth was so strong that when he would publish comic war stories, he would sometimes write from the point of view of a North Korean or a Japanese soldier.

Yes. Harvey was a purist. You have to give credit to guys like that, because while most of us just sit back and do the same thing over and over again and try to make a living out of it, Harvey was not interested in becoming rich. He was interested in new boundaries to conquer. He just wanted to create and create and create.

He sounds like a dreamer, in a sense.

He was a dreamer. But there was also a very practical side to him. He knew what he was doing, but he didn’t find compromising an easy thing to do. And if you have to depend on other people’s money to subsidize you, you have to compromise.

Is it true that Harvey wanted to reach out to Norman Rockwell for MAD?

It is. I really don’t think we could ever have gotten Norman Rockwell. But Harvey was not a relegator. He would have looked at what Rockwell created and just said, “Look, here’s what I would really like to have in this. Could you do that instead of this and this instead of that?”

Where did you go after Trump folded after the second issue?

Harvey then created a humor magazine called Humbug. And we all invested in it.

Invested not only time, but money?

Yes. I invested all my money.

And how long did Humbug last?

I think about 14 months, 11 issues.

Why do you think Humbug failed to succeed?

Money had a lot to do with it, but also, I think we made a blunder in wanting to be different. Harvey said that we had to do something to stand out, and making it smaller than other magazines was the way he wanted to go. But I had heard from news dealers that they didn’t know where to put it because it would fall behind other magazines and no one would ever see it. That’s just what I was told — I have no reason to believe that that’s what really happened, so I really don’t know.

It was a big influence on a lot of the illustrators and humorists at the time, though. I met R. Crumb when we were doing Humbug, and he was very complimentary to me. Looking back, I can see why he was complimentary, because my work was very similar to his work.

How did you end up getting hired again by MAD after your experience at Trump and Humbug?

In the late 1950s, I went to MAD with some scripts, and the new editor, Al Feldstein, bought all of them. Al was a very hands-on editor. No MAD piece was ever bought without his approval. We respected each other’s talents, and I think he was a very good editor and a very smart man. He also knew how to delegate, which Harvey never knew how to do. And he was a lot more flexible than Harvey, a lot less rigid in his outlook — at least in my experience.

Al Feldstein brought onboard a lot of the writers and artists we now associate with MAD.

He did, yes. He brought Don Martin to the magazine, as well as Antonio Prohías, who created “Spy vs. Spy.” Also, Dave Berg, who created “The Lighter Side Of …”

What was Dave Berg like as a person?

Dave had a messianic complex of some sort. He was battling … He had good and evil inside of him, clashing all the time. It was sad, in a sense, because he wanted to be taken very seriously and, you know, the staffers at MAD just didn’t take anybody seriously — most of all, ourselves.

Do you think Dave Berg’s inner battle later expressed itself in his strip “The Lighter Side Of …”?

It came out in a lot of the things he did. He had a very moralistic personality. I mean, he moralized all the time. And his gags were very suburban middle-class America. Plus, he was very religious. He wrote a book called My Friend God. And, of course, if you write a book like that, you just know that the MAD staff is going to make fun of you. We would ask him questions like, “Dave, when did you and God become such good friends? Did you go to college together, or what?”

I think Dave had a feeling that his contribution to the success of MAD wasn’t appreciated enough, and I think this bothered him. He once told a staff member that he received so much fan mail that they had to hide it from him. Naturally, most of us would just roll our eyes, because we didn’t expect tons and tons of fan mail, and if there was fan mail, we always received it. I guess Dave felt he was carrying the whole magazine, and he should have been treated royally.

Tell me about the quintessential MAD contributor, Don Martin.

Don Martin was the very opposite of what he drew. He was a very nice-looking guy: tall, handsome, extremely soft-spoken. You almost had to bend forward to hear what he was saying. He didn’t crack jokes, and he didn’t do funny stuff, but he was a great appreciator of the humor of other MAD contributors. He was a great listener, and he laughed a lot and had fun, but he was not demonstrative — not at all. I guess he got it all out in his drawings.

He was a fantastic illustrator. His work for MAD was almost like animation. You could visualize his characters moving on the page; you could feel the action. And those sounds he came up with, well, they were not easy to create. With most of the contributors, if we needed sound effects, we tended to stick to the tried-and-true. For instance, we would use sounds such as “boff” and “zock” and “pow” and “bam.” But Don went much further, by creating his own language: “pwang,” “splitch,” “splawtch.” If you read the words, you could hear those sounds. That is just universal and completely unique. And that material hasn’t dated at all; it’s just as great as it was when it came out. He was really special. Sui generis.

Was there a sense of camaraderie in the golden age of MAD, from the early ’60s through the mid-’70s?

Oh, a great deal. Absolutely! MAD’s publisher, Bill Gaines, did something very clever: He would take the whole staff on an annual trip abroad. And we lived together for anywhere from seven to 17 days. We hung out together, we all went out to restaurants together, and we got to know each other. We became almost like a family. I mean, we weren’t in an office environment day-to-day where we got to know each other. A lot of us worked from home. In fact, every artist and writer worked from home — only the editors and art directors worked in the office.

These trips were also an inducement to produce more material; if you didn’t hit your cutoff each year, you weren’t allowed on the trips. In the beginning, it was 20 pages of published material, and later you had to produce 25 every year. The trip was a reward for increased contributions. I was one of a few contributors who was on every single trip. I never missed the cutoff. Our first vacation was to Haiti in 1960.

Why Haiti?

We went there to pay a visit to the one and only Haitian subscriber to MAD. On the entire island, there was only that one subscriber, and he had let his subscription lapse. So when we got there, Bill Gaines took a bunch of writers and illustrators over to this guy’s house and knocked on the door. When the guy answered, Bill offered him the gift of a renewal.

You also visited the Soviet Union in 1971 and to the office of its perhaps one humor magazine.

Yes, Krokodil.

What was the mood like in that office?

Very strange. It was so controlled. It’s almost like the archetypal Soviet scene where a group of politicians are sitting around the table.

Humor by committee.

Yeah. Exactly. We asked them if they could do things like we do, and they sort of hemmed and hawed and hedged. But basically, they couldn’t do anything but the official propaganda.

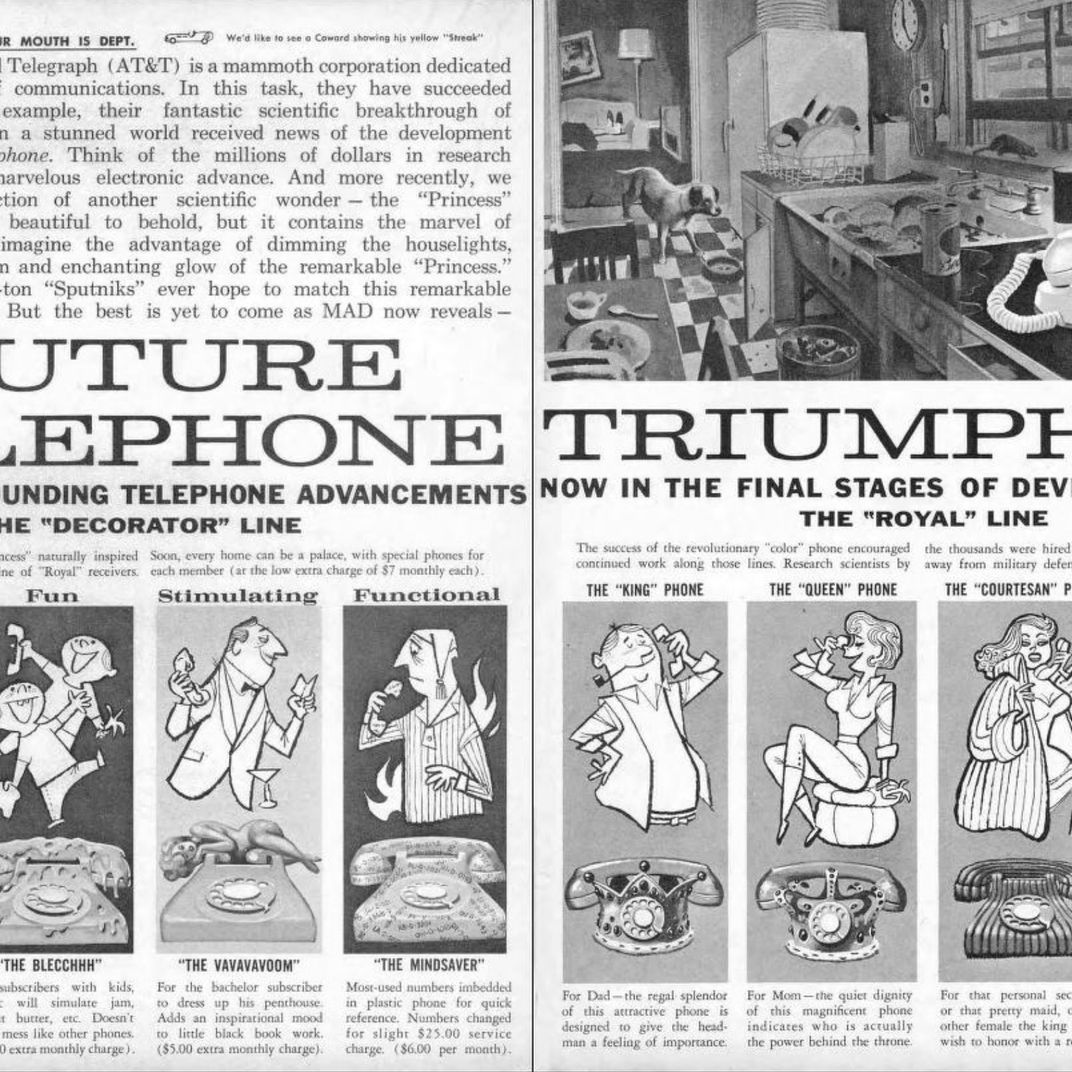

In rereading your MAD articles, I found that you predicted, or perhaps even invented, quite a few modern-day products.

I did?

I’ll give you a few examples. In a piece you did in March 1967, you drew an illustration of a machine, and wrote, “The Idiot-Proof Typewriter will include memory tapes and store millions of words, phrases, and correct grammatical expressions.” Sounds very similar to the spell-checker on a word processor.

Wow! I don’t remember that.

You predated the redial option on telephones and a cell phone’s address book when you came up with the “automatic dialer” in 1961. Punch cards were inserted into a phone, which then automatically dialed the saved numbers. And you created “snow surfing,” basically, snowboarding, in 1965: “Using a regular surfboard, the Snow Surfer has trees, rocks, and annoyed skiers to lend dangerous excitement.”

No kidding.

You don’t remember these?

I don’t remember, no. I’ll have to read your book.

From MAD #98, October 1965.

From MAD #172, January 1975.

From MAD #66, October 1961.

From MAD #98, October 1965.

From MAD #172, January 1975.

From MAD #66, October 1961.

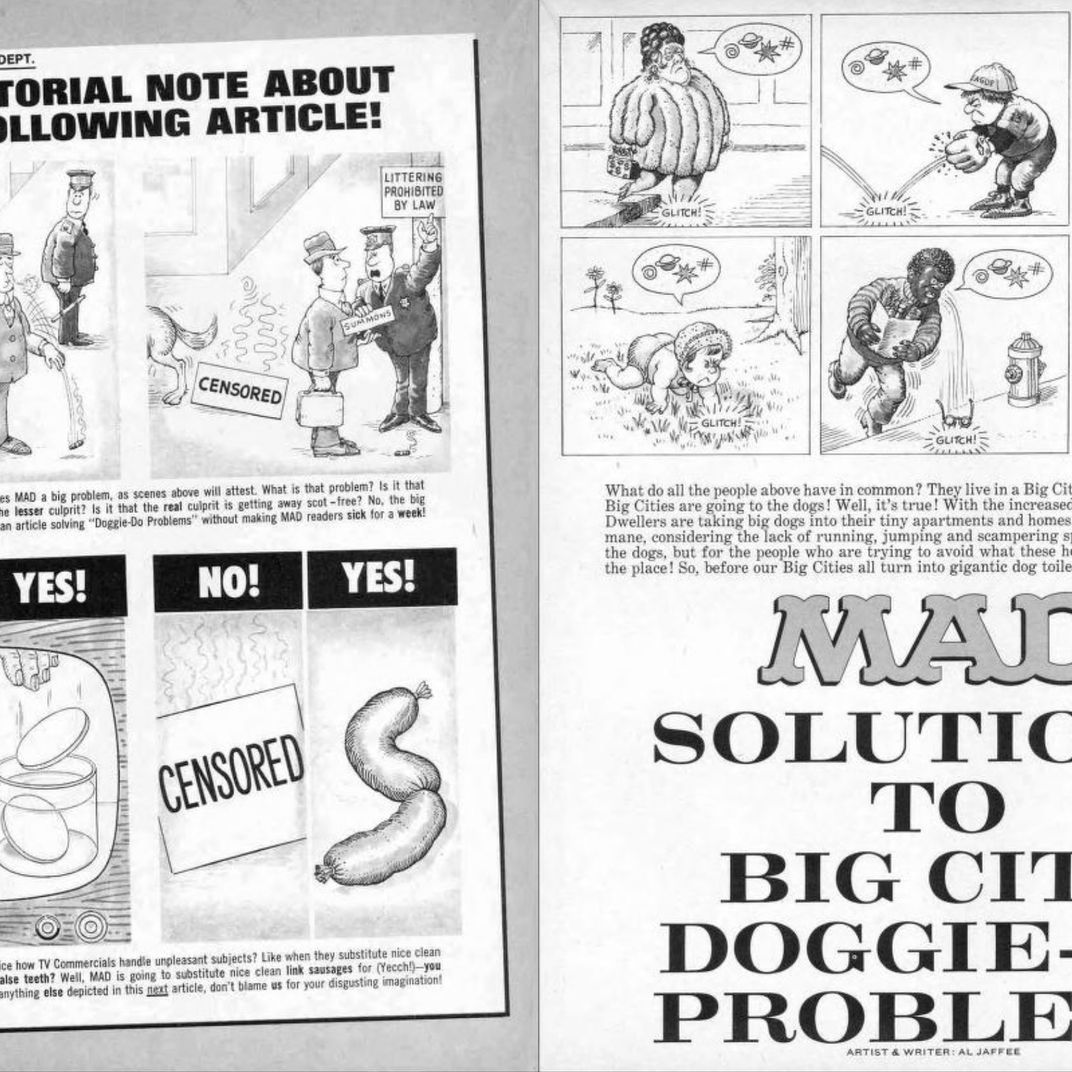

You’re being too modest. You also came up with the peel-away, non-lickable stamp in January 1979; the three-blade razor in July 1979; the “vandal-proof building” that repelled graffiti in 1982; and, my personal favorite, from the January 1975 issue, the “acrylic plastic squirt gun” for “doggie doo.” When the bulb is squeezed, “two chemicals are forced to mix and squirt from nozzle,” covering up excrement. That device has since actually been invented.

Ah, yes. I remember that one.

You should have patented those! You would have made a fortune!

No, no, no. I could imagine those types of things, that was the fun part. But I never had the problem of trying to figure out how to manufacture them.

Did you have any scientific training?

None at all. My father used to manage a department store in Savannah. Later, during the Depression, he had to earn a living as a postal worker. Before we all left for Lithuania, my father would take my brothers and me, every Saturday, to the toy department, and we’d just have a ball there. Then we wound up in this little village in Lithuania with no toys whatsoever. We invented toys out of just scraps of wood lying around the yard. My brother Harry actually made a fire truck that sprayed water. Oh, God, we invented all types of ingenious things! We came up with a device that enabled us to steal fruit from neighbors’ yards. It was a pole with a knife attached to the end, and then a basket for the fruit to fall into. So I think all of the inventions came from an interest in seeing what you can make for yourself if you’re not able to go to the store and buy it.

Speaking of ingenious inventions, tell me about the MAD “Fold-in.” How did you first come up with the idea?

At this time — this would have been in April of 1964 — every major magazine was publishing some sort of foldout feature. Playboy, of course, had made it big by having a centerfold. So did Life magazine. They would have one showing, say, the geography of the moon, or something like that. Even Sports Illustrated had one at one point. So, naturally, how do you go the other way? You have a fold-in, rather than a fold-out. I created a mock-up, and wrote on it something like: “All good magazines are doing a foldout, but this lousy magazine is going to do a ‘Fold-in.’” I went to Al Feldstein and showed it to him, but I didn’t think the idea had a chance in hell of being used.

Why not?

Because it mutilated the magazine.

There were no advertisements in the magazine at that time. To mutilate an ad might have been a problem, but why would it have been a problem just to bend an article?

Yes, that’s a good point. All I know is that when I showed the idea to Al and said, “You’re not going to want to do this, but I think you’ll get a kick out of it,” he looked it over and said, “I like it. Let’s do it.” I figured it was a one-shot deal, just a gag. Everybody had these beautiful color foldouts. And we had a stinky black-and-white “Fold-in.”

What was the first “Fold-in”? Do you remember?

Liz Taylor and Richard Burton. Rumors were flying around at that time — this was 1964 — that Liz was involved with Burton. I drew a crowd scene outside a Hollywood event, with reporters and fans. Liz was on the left and Richard was on the right, and Eddie Fisher was somewhere in the middle, on the ground. When you folded it in, Liz winds up kissing a handsome stranger. And Eddie Fisher was completely out of the picture. So, you know, it was a very simple thing.

It was so simple at first that it was almost childish. But I kept working on it and honing it through the years. Eventually, the “Fold-in” evolved into what we have now, more than 40 years later, which is far more complicated. I’ve done more than 400.

You took on a lot of serious issues with these “Fold-in”s over the years, such as Vietnam, the Exxon Valdez, abusive parents, and homeless veterans. Was this an outlet for some of your anger over what was going on in the world?

Not vehemently, but sometimes it became an outlet. It’s a strange duck. One picture turns into another picture. But you have to say something. You can’t just have an illustration. It’s better to make a comment about the world around us. One of the editors at MAD, Nick Meglin, once said to me, “The ‘Fold-in’ is the only editorial cartooning done in MAD.” And I guess that’s true.

How long does it take to create each “Fold-in”? What’s the process?

I’d say about two weeks from start to finish. I no longer look at it as being something formidable, because I’ve done it for such a long time. I have the feeling now that no matter what it is, I can find a way to do it. But it’s still a challenge.

From MAD #273, September 1987.

From MAD #248, July 1984.

From MAD #168, July 1974.

From MAD #109, March 1967.

From MAD #208, July 1979.

From MAD #273, September 1987.

From MAD #248, July 1984.

From MAD #168, July 1974.

From MAD #109, March 1967.

From MAD #208, July 1979.

Is it true you never know whether the final version will work or not?

I never see it folded until it’s printed.

So how do you know if it’s going to work?

I just do. The final illustration is on a flat cardboard piece. But if I have any doubts, I can make a Xerox copy and then cut it and move the two pieces together. But I do make sure that everything connects, and I do that very simply. I have a strip of transparent tracing paper. I lay it down on one side, and I use a pin to hit all the points that are going to touch.

And then I move that over to the right side, and I do the same thing on the left side. And anywhere that it doesn’t match, I make the correction.

Have you ever looked at a “Fold-in” you created years ago and actually tricked yourself?

Actually, I have, yes. I’ve looked at some old issues of MAD where I don’t remember what the “Fold-in”’s answer is. I can’t figure it out — which either means I’m a numskull or I’m doing a pretty good job on this thing.

Why do you think the “Fold-in” is so popular with readers?

Because it’s a puzzle. It’s a participation thing, whereas with the rest of the magazine, even though a reader may come across pieces that are ten times more interesting or hilarious, they just absorb it. They soak those pieces up, and then they come to my piece and can’t absorb it. All they can absorb is half of it. Then they have to do something to get to the other half. I think that creates a little element of interest.

Some of your pieces in MAD over the years have been very, very dark. I’m thinking in particular of the piece in which a doctor announces to a family that a relative has died. The family turns away and walks out. But the patient then moves, he’s still alive …

And the doctor hits him over the head with a hammer and kills him.

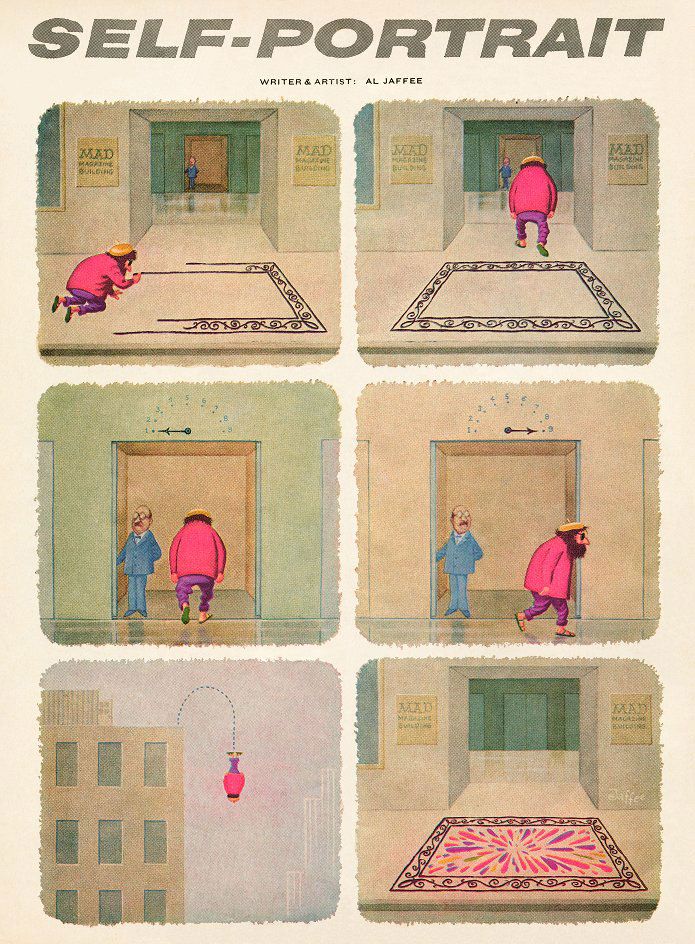

I’m also thinking about another piece called “Self-Portrait.”

Where an artist jumps off a building and his splatter produces the work of art.

Now that’s very subversive, especially for a magazine that one might consider aimed at kids of a certain age. Were there ever any ideas that you deemed too dark to work on?

Everyone has their own sense of what’s in good taste or what’s in bad taste. I think a lot of it has to do with the execution. James Thurber once did a cartoon of two people dueling, and one of them has lopped the head off the other one. And the caption reads “Touché,” which is brilliant. Apparently another cartoonist was going to draw this cartoon, but he was too realistic an illustrator. But Thurber could get away with it, because his style was less realistic. Nobody was offended.

So everything has to do with how you carry it out. That one I did with the artist jumping off the building, he was clearly a cartoon character. It’s all a matter of execution. Execution is everything.

Do you get money from MAD when they republish your articles in books and such?

We don’t get any … what do you call it? Residuals, no.

Over the years, how have you managed to keep up with the current pop-culture trends?

To be truthful, I don’t. I’m a little too old to be able to keep up with the fashion trends of 20-year-olds and their music tastes. All you can do is read the newspapers and magazines and try to get a feeling for it. Also, I watch my children and grandchildren and see what they’re doing.

Did you feel the same way 20 or 30 years ago?

I think one of my strong suits is I never became infatuated. I’ve always been on the outside looking in. It goes all the way back to Lithuania, where some of my friends were obsessed with certain leaders of the community as if they were rock stars. But I’d sit off to the side and say, “What do they see in that guy? He’s just an old goat.”

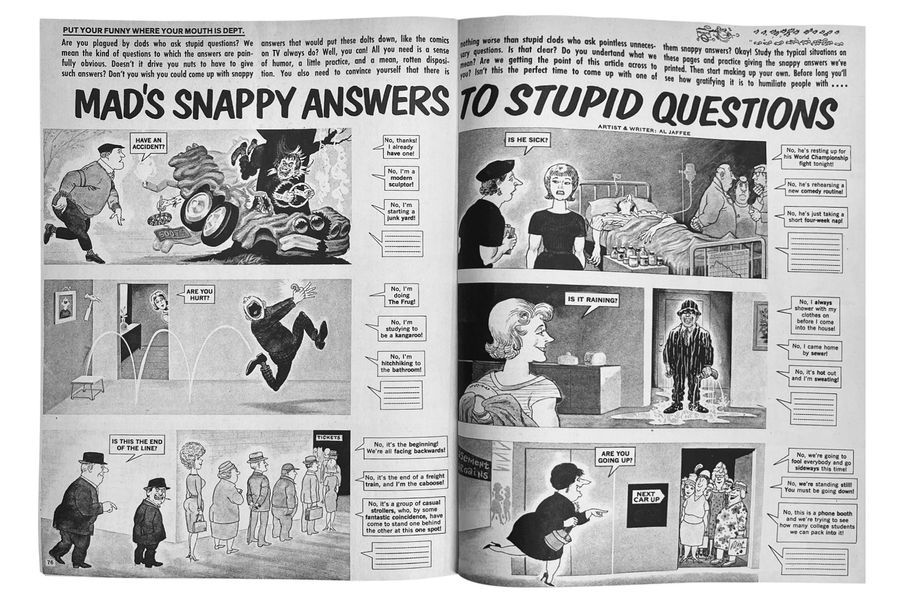

How did “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” get started in 1965?

The way it got started is how a lot of things get started: You experience something, a little experience, and that leads to an idea. I happened to be standing on the roof outside my house on Long Island trying to fix an antenna, which had been blown over in a storm. And I’m afraid of heights, so I was very nervously tightening the band around the chimney that held the antenna. Suddenly, I heard my son climbing up this ladder. He asked me a question that he asked every time he came home from school: “Where’s Mom?” And I answered, “I killed her and I’m stuffing her down this chimney.”

He knew I was kidding, obviously, but I thought about this afterward, and it occurred to me that there must be a million times a day we all get asked questions to which you either don’t know the answer or it’s a pointless question. Up on the roof, how the hell would I know where Mom was?

I think the brilliance of “Snappy Answers” is that the last entry is always left blank for the readers to fill in with their own jokes. I wonder how many professional humor writers got their start writing jokes in those blanks?

Oh, I don’t know. Those of us who work in the world of writing and drawing have very little idea of what kind of connection we’re making. I mean, some people might come up to you and say, “I loved that thing you wrote,” but there are thousands of others who’ve read it and you never hear anything from them. That’s why I’m always very, very flattered when someone remembers something that I did.

What are your thoughts on the future for comic-book illustrators? For a humor writer, one would assume there will always be television or the movies. But illustrating for a comic book like MAD seems so specific a talent. Do you think it will survive?

I think there are going to be some drastic changes as far as commercial artists are concerned. Even as you were speaking, I was picturing getting up in the morning and a favorite comic strip is on a panel and it rolls by and it’s animated. No longer will it be “Peanuts” with four panels and static little figures. Now it will feature characters walking or kicking a football right in front of you — all on a sheet of something that is no bigger than a page. All of that is bound to come. Truthfully, I don’t know what we’re going to gain or what we’re going to lose. Of course, you both gain and lose from the advance of knowledge and technology. But humor, I don’t think any race of people can survive without it.

You’ve been at MAD longer than any other writer or artist. You’ve been published in more than 400 issues. And yet you said something recently that I found intriguing: “If I were fired tomorrow from MAD, I think the old creative juices, the old inventions, would surge.” My question is how much more do they need to surge? You’re still going strong.

I’m taking the easy path now. I’m doing things that are available to me, rather than going out and inventing new things and proposing them, because I just don’t have the energy to become a salesman for these ideas. I find it really satisfies my creative instincts to do just a “Fold-in” once a month. I think the “Fold-in” is my last hurrah.

Will you be willing to give me a snappy answer to a stupid question? How do you think you’ll be remembered?

Is space available on Mount Rushmore?

Maybe I should leave the last line blank so the readers can fill in the answer for themselves?

Sounds good. Do it.

Special thanks to Christopher Bonanos and Ian Scott McGregor.

Mike Sacks is a contributor to Vulture, the New Yorker, and other publications and is the author of ten books, two of which (And Here’s the Kicker and Poking a Dead Frog) are collections of interviews with comedy writers.