Ryuichi Sakamoto died in March 2023, but many of us had been steeling ourselves for the news since the previous December, when he performed what he himself suspected might be his final concert. After years of dealing with cancer, the Japanese musician (known as “the Professor” to many of his fans) could no longer tour, nor could he do any kind of sustained live performance. So the solo concert, entitled Ryuichi Sakamoto: Playing the Piano 2022, had been created across a few days out of pre-recorded segments that were then assembled and streamed around the world.

It was a beautiful, profoundly sad farewell. But it was his to give, and to share. You could see the emotion on his face as he sat at his piano and returned to the songs he had played so many times over the years. The setlist included pieces from his days at the vanguard of electronica as well as memorable works from a 40-year film-composing career.

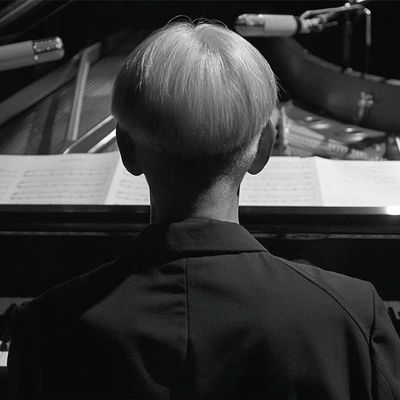

An expanded version of that concert now exists as a feature film, which premiered at the Venice and New York Film Festivals last year and is opening in U.S. theaters. A spare, lovely work directed by the late musician’s son, Neo Sora, Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus is even more haunting on a big screen, where its shimmering black-and-white photography and elegant camera moves actually heighten the intimacy of the performance. As Sakamoto communes with his music, we feel like we might be intruding on a private requiem. At times, he seems to be playing for himself. Are those reflections in his glasses tricks of the light, or are they tears?

It’s all intentional, of course. Sakamoto was a savvy and thoughtful performer — never doing anything by rote, often improvising, aware of his audience and in playful conversation with them. Throughout his final album, 12, which consists of 12 tracks, most of them a combination of solo piano and ambient soundscapes, we can hear his breathing — straining over the keys, perhaps, but also simply reminding us that he’s there, his presence lending a delicate, human rhythm to the pieces. This self-awareness runs throughout his late works.

Sakamoto had always been fond of experimentation, but over the past couple of decades he had become even more fascinated by the possibility that any sound could become music. Alarmed by the effects of climate change, in 2008 he traveled to the Arctic sea with a hydrophone and recorded the sound of trickling water inside a glacier, turning it into several tracks. The 2017 documentary Coda shows him at his apartment in New York, experimenting with recording the sound of rain, scraping cymbals and other objects in his studio and listening to the noises they make.

That same film shows him reclaiming a piano that was stuck in the floods caused by the 2011 Japanese tsunami. “I felt as if I was playing the corpse of a piano that had drowned,” he observes, noting that pianos are objects over which manmade design and natural imperative are constantly in conflict — “six planks of wood overlaid and pressed into shape” that then fall out of tune as they return to their original state. Sakamoto’s 2014 cancer diagnosis not only made him reflect on his own mortality, but also on the fact that his own body was an object acted upon by time and nature. And thus, another instrument for him to play with.

Sakamoto doesn’t seem particularly frail during his performance in Opus. He’s gaunt, but he was always pretty gaunt. The fragility lies in the music, in the vulnerability with which he plays it, and in the austere cinematic presentation. He’s performing inside Studio 509 at NHK, the biggest and most impressive of the Japanese public broadcasting company’s recording stages, and he’s playing a Yamaha grand built specially for him, but there’s no ostentation here; by the end, the only source of light seems to be one small lamp over his shoulder. In that sense, too, Opus represents the culmination of a lifelong journey from effusive maximalism to gentle simplicity.

Sakamoto had initially risen to fame in the late 1970s as a technopop pioneer, a member of the Japanese trio Yellow Magic Orchestra, whose dense, synth-heavy beats, boldly layered compositions, and witty embrace of computer-age aesthetics revolutionized dance music. As a solo artist throughout the 1980s and ’90s, his music was bewilderingly eclectic and vibrant, constantly mixing and matching influences and contributors from all over the world. This was the era of “World Music,” defined by its geographic multivalence. Sakamoto had been born and raised in Japan, but he had grown up immersed in European classical music, and eventually settled in New York. One of his best-known works is “El Mar Mediterrani,” composed for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics in Spain. Artistically, he saw himself as something of a man without a country.

Maybe that was his secret. For what might be his most beloved piece, the theme song to Nagisa Oshima’s 1983 film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (in which he also co-starred, alongside David Bowie) Sakamoto fused the Western idea of Christmas bells with sampled Javanese percussion sounds; in interviews, he described it as music from a country that didn’t exist. At the time, Sakamoto had never created a soundtrack (he would go on to become one of the great film composers of his age), and his inexperience resulted in a score that often worked against the action onscreen and that he later felt drew too much attention to itself.

Of course, that’s why it works. Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, about forbidden homoerotic longing in a Japanese POW camp, is filled with scenes of terrible cruelty, but beneath so much of the violence lies unfulfilled desire, and Sakamoto’s music opens new emotional doors that the onscreen story merely approaches. As played in Oshima’s film, the central theme is loud, brash, and alien. When played on a solo piano, however — which is how Sakamoto performed it in later years, and how he performs it in Opus — you sense its velvet tenderness, its otherworldly optimism. Reduced to its essence, it’s a love song.

That’s probably the most transfixing aspect of Opus, particularly for those unfamiliar with Sakamoto’s later solo performances. (There was a Playing the Piano in 2009, and a Playing the Piano in 2011, and in April 2020 another livestreamed concert called Playing the Piano for the Isolated, an effort to entertain a lonely world in quarantine.) Stripping his best-known and most beloved pieces down to their essentials, he showcases their resonant rising melodies, giving them a sound both timeless and modern.

I became obsessed with Sakamoto’s music as a teen, through his scores for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 epic The Last Emperor (which won him an Oscar) and The Sheltering Sky (1990). Those memorable themes have been trusted standbys in his regular repertoire, and they make their expected appearances in Opus as well. But the piece I now find most fascinating is “Happy End,” which he plays near the end of the new film (right before “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” his biggest hit). “Happy End” dates back all the way to Sakamoto’s early years, both as a solo artist and with the Yellow Magic Orchestra. Back then, the song was a fast, visionary whatsit, all pulsing, pipe-like synths and simple, buzzing one-bit melodies. Sometimes in concert, it was performed with slashing drums and swirling, dissonant improvisation that buried its plaintive main theme. Later, Sakamoto would perform it as a staccato piano piece with string accompaniment and low electronic beats.

As he transformed, the song transformed, seemingly fitting with whichever new direction had struck his fancy. Because at the heart of it was a melody that could hold up to any kind of arrangement: guitar, harpsichord, bouzouki, full orchestra, you name it. Here, as Sakamoto plays “Happy End” for one last time, reduced to its basics, we’re struck by what it really is — a stirring pastoral, imbued with an aching sense of freedom and an almost rousing sense of possibility. It’s a song of horizons and of movement, a passage perhaps from one country that doesn’t exist to another.

More Movie Reviews

- Fernanda Torres Is a Subtle Marvel in I’m Still Here

- Grand Theft Hamlet Is a Delightful Putting-on-a-Show Documentary

- Presence Is the Best Thing Steven Soderbergh’s Done in Ages