In the early 1990s, the conceptual artist Gillian Wearing began to make a name for herself creating confessional, guerilla-style performances with volunteers she sourced on the street or in newspaper advertisements. At the time, she was a 20-something grad from Goldsmiths College in London; eventually, she would become known for these emotionally intense projects, which tap into the tension between repression and revelation.

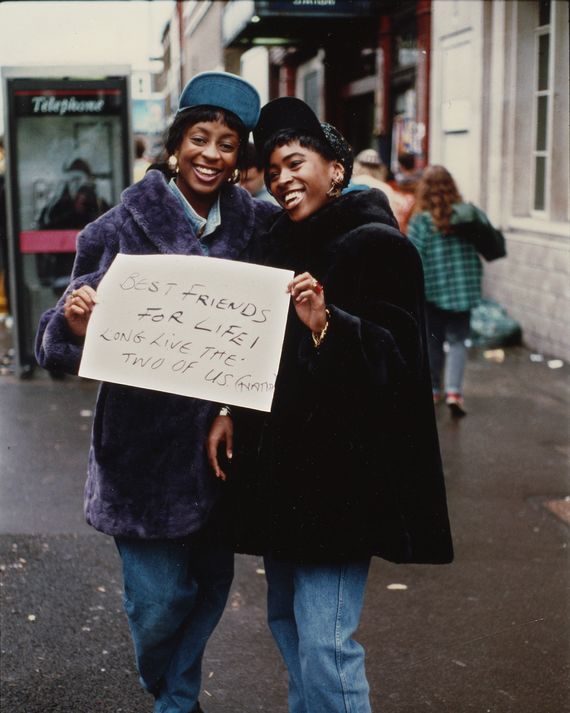

Starting in 1992, in a series titled Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, she enlisted strangers to fill out blank pieces of paper with whatever thought came to mind and to pose for photographs holding them; in one image, a white man in a suit with a mirthless smile holds the message IM DESPERATE, while in another a puckish teen flashes the sign: GIVE PEOPLE HOUSES THERE IS PLENTY OF EMPTY ONES OK! In 1994, the year that MTV released The Real World and invented the confessional, Wearing asked a group of strangers to share secrets about their lives on-camera. Participants wore wigs and masks to obscure their identities while they told intensely intimate stories about their childhood trauma or various sexual transgressions. The film is titled, rather absurdly: Confess All on Video. Dont Worry You Will Be in Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian 

Wearing quickly ascended to recognition as one of the Young British Artists, or YBAs, defined by their use of unusual, sometimes shocking materials: Damien HirstÔÇÖs preserved tiger shark, Tracey EminÔÇÖs bloodied underwear, Sarah LucasÔÇÖs fried eggs. The YBAs were seen as iconoclasts and provocateurs, many of whom seemed comfortable in the public eye. Wearing, however, preferred to be anonymous ÔÇö the conductor with her back turned to the audience. ÔÇ£When I made my first works, people often didnÔÇÖt know who was behind them or what my gender was,ÔÇØ she later said.

WearingÔÇÖs work was eventually absorbed into the art worldÔÇÖs commercial machinations. Two decades after she made Confess All on Video, she paired with Wieden+Kennedy ÔÇö the ad agency known for its work with Nike and Coca-Cola ÔÇö to film AI-generated versions of herself and superimpose them onto the bodies of actors. The composite avatars are garishly lit, emblems of the uncanny valley. The video, which is called ÔÇ£Wearing, Gillian,ÔÇØ feels glitchy, unreal, and vaguely promotional, offering only a mirage of the artist. Her face is inescapable in the film, but because all of the images use face-swapping technology, the viewer is unsure if she is even really there. Much of WearingÔÇÖs work pokes fun at the impulse to conflate a personÔÇÖs appearance with their psyche and private sense of identity. Though she often uses herself as a subject, weÔÇÖre left with an incomplete, warped, and fragmented sense of who she is.

ÔÇ£Wearing Masks,ÔÇØ the artistÔÇÖs first retrospective in the U.S. and now on view at the Guggenheim through April 4, features more than 100 of WearingÔÇÖs artworks ÔÇö including photographs, paintings, videos, and 3-D-printed objects. (ItÔÇÖs not WearingÔÇÖs only presence in New York right now: In October, her cast-bronze sculpture of Diane Arbus, organized by Public Art Fund, was unveiled at the entrance to Central Park.) Organized in the hard-angled gallery rooms adjacent to the rotunda, the Guggenheim exhibit traces the now-57-year-old artistÔÇÖs shift from publicly engaged performance maestro to introspective studio practitioner. Interspersed over the exhibitÔÇÖs four floors are scintillating photographs and films that capture the theatrics of the everyday, full of alienation and vulnerability. It makes it clear that, at her best, WearingÔÇÖs work can be thrilling and moving and deeply unsettling, a smorgasbord of humanity.

Co-curators Jennifer Blessing and Nat Trotman organized the show partly chronologically and partly thematically. That approach can sometimes feel scattershot. There are several thoughtful pairings ÔÇö like WearingÔÇÖs deeply felt black-and-white film about the troubled dynamic between a mother and daughter, Sacha and Mum from 1996, positioned close to ÔÇ£Snapshot,ÔÇØ a series of flickering images of unrelated women at different life stages that she made in 2005. But the layoutÔÇÖs narrative through-line mostly befuddles, making it hard to grasp WearingÔÇÖs evolution as an artist.

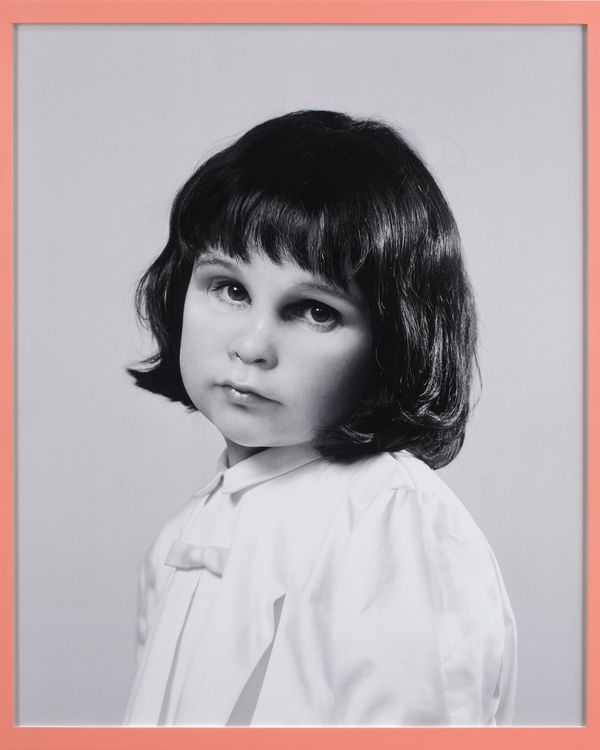

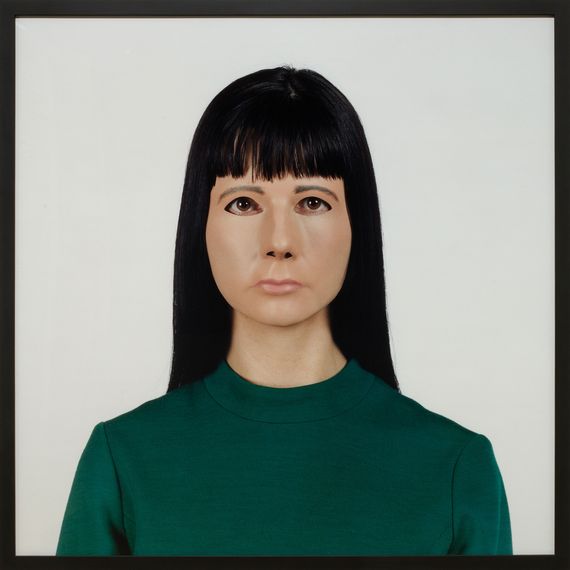

The most memorable work in the show is WearingÔÇÖs photo series ÔÇ£Family Album,ÔÇØ which she began in 2003. Transcending age and gender in meticulously planned photographs, she transforms into her grandmother, mother, father, brother, and younger versions of herself, wearing uncanny masks of these different faces ÔÇö created with help from experts trained at Madame Tussauds ÔÇö as well as wigs that range from her motherÔÇÖs coiffed bob to her grandfatherÔÇÖs salt-and-pepper receding hairline. Each image is a re-creation of specific portraits of her family members, and the result is eerie: In a photograph where Wearing is dressed as her mother, we see a 1950s housewife with a cold, distant glare; in another, sheÔÇÖs dressed as herself as a little girl, with a doll-like face that is lined with subtle but distinct mask marks.

On the next floor of the show, we encounter a room of more luminous self-portraits, which she started to make in the early 2000s. In every photograph of this series, called ÔÇ£Spiritual Family,ÔÇØ Wearing shoots herself in restaged, iconic images of legendary artists, again with her face obfuscated by lifelike, silicone masks. In one work the artist poses, convincingly, as pop artist Andy Warhol, who himself is in drag as a woman. She dresses as Arbus, Georgia OÔÇÖKeeffe, Robert Mapplethorpe. By wearing other artistsÔÇÖ features and adopting their gestures, Wearing seems to both align her artistic vision with theirs, and, paradoxically, to reveal the absurdity of the myth of the artist as genius. The masks form creases under her eyes, along her jawline, around her nostrils. Displayed in larger-than-life prints, the photos are both beautiful and disturbing, cartoonish in their bravado as they insert Wearing into the canon.

If there is any one idea that unites WearingÔÇÖs projects, itÔÇÖs that the self is fundamentally unknowable. Her work in the ÔÇÖ90s and early 2000s examined the misalignment between public selves and private lives with a spirit of open-mindedness ÔÇö┬áwhereas the more recent work in this exhibit falls flat precisely because it seems intended to evoke a specific response from viewers.

In 2013, Wearing started working on Your Views, a crowdsourced film project for which she put out an open call online and received more than 800 submissions from Hong Kong to Abu Dhabi to Kabul to New York City and Kolkata. Her goal was to feature at least one video clip from every country around the world, which sheÔÇÖs described as ÔÇ£a project that could connect people and countries, that was simple and universal.ÔÇØ The composite footage, displayed on a monitor at the Guggenheim as one continuous, nearly three-hour-long stream, is poignant in its subtle details ÔÇö a bird taking flight, laundry blowing in the wind ÔÇö but tends to lose power in the specifics. Some of the most recent scenes, filmed by people who are ostensibly in quarantine, show their neighbors gathering on front porches to clap for health-care workers. In light of recent division over COVID-19 misinformation, racial inequities in health-care access, and global disparities in vaccine availability, the image does not express universal togetherness so much as replicate a hollow gesture.

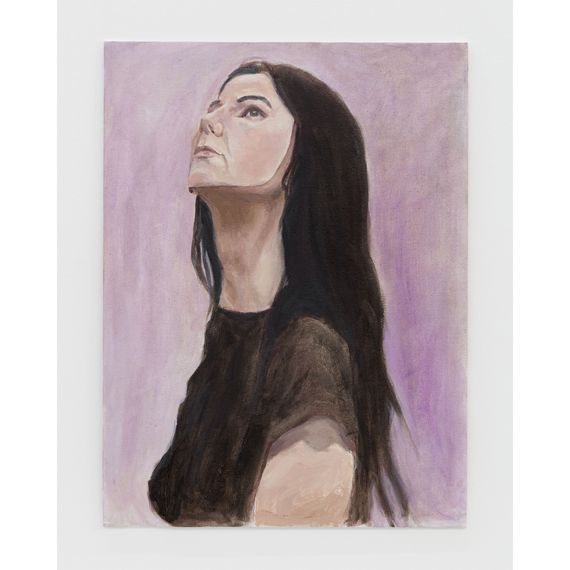

The most recent works, displayed in the uppermost room of the museum, are melancholic watercolors and paintings that the artist made at her home in London during the early months of the pandemic. The ÔÇ£LockdownÔÇØ series is a departure from WearingÔÇÖs inventive photographs and videos: The realistic self-portraits depict idle moments, where the artist is lying in bed or leaning against a wall, in watery blues, faded browns, and soft pinks painted directly on board. Seeing them in late 2021, unfortunately, casts them as the visual analog of the now-clich├® pandemic diary ÔÇö whose writers, as Parul Sehgal noted, ÔÇ£are an unusually cocooned bunch, safely distant from the world of layoffs, mass graves, Zoom funerals.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs little room for interpretation when the images are so heavy-handed. In the case of Mask Masked, a wax sculpture of a hand and hollowed face, a fabric mask is, quite literally, on the nose.

In WearingÔÇÖs most successful projects, sheÔÇÖs a chameleon, eschewing tidy narratives in favor of ambivalence and complexity. In trying too ardently to produce work that could be topical, Wearing veers off course. Her pandemic portraits make you long for a return to work like Dancing in Peckham, her 25-minute video documentation of a performance from 1994. Standing in the middle of a South London mall, the artist sways, twists, and nods her head, dancing not to music but to everyday sounds. It was the first time Wearing had appeared as the subject of her own work. The fascinated and at turns disturbed stares she attracts from passersby distill what made her early work so powerful: It expressed the strangeness of being perceived at all.