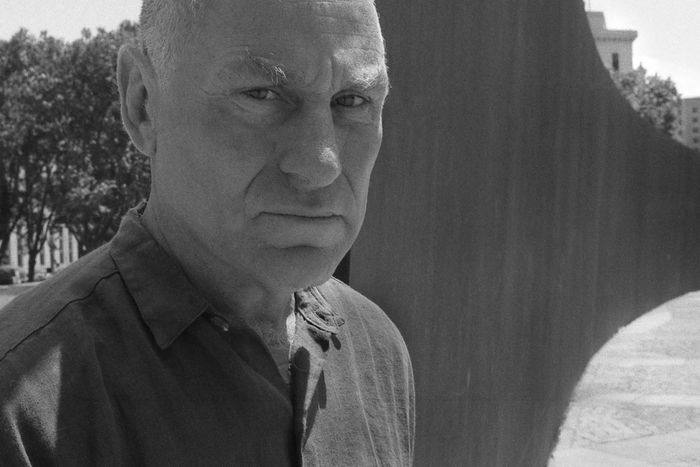

Richard Serra, who died on Tuesday at the age of 85, was a powerhouse locomotive of American art. His colossal steel plates are coiled like ribbons into spiraling geometric shapes reminiscent of rosebuds and eddies and shaved chocolate. These megaliths are so massive that they usher us, through shadowed slivers, into their enclosed spaces, where one stands alone with — and within — art. Here is silence and material and scale and movement.

Serra transformed sculpture. He was a working-class alchemist originally from San Francisco; as Janet Malcolm once said, “his aura was of rough small-town America rather than of bohemia.” In New York in 1968, he took on Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists, but instead of paint, he splashed molten lead onto the base of a wall. Ladle by ladle, he showed liquid becoming solid, revealing sculpture as an action just as it was freezing into form.

In 1969, he leaned four quarter-ton plates of lead against one another in a rough cube and titled it One Ton Prop (House of Cards). These dangerous balancing acts — thrust and counterthrust, weight and angles and centers of gravity — would come to define his work, which often seemed on the precipice of collapse. Your antennae twitch, wiggle, and grow before a Serra.

Delineator (1974–75) is composed of two rectangular steel plates, each measuring 10 feet by 26 feet and each weighing two and a half tons. One rests on the floor. The other is attached to the ceiling, hovering over its partner like a section of the Cross. You are invited to “enter” the work and stand in the area between the two masses. “You’re forced to acknowledge the space above, below, right, left, north, east, south, west, up, down,” Serra said. “All your psychophysical coordinates, your sense of orientation, are called into question immediately.”

There are no special effects here. From above, Sequence (2006) resembles a giant swirling confection from a bakery. It consists of 12 enormous steel plates that collectively weigh 235 tons. In its austere metal planes, you nonetheless sense the soaring forms of the Baroque, the enticing lyricism of the rococo. Kazimir Malevich once said he wanted to reach “the zero of form”; Serra does this while still creating something.

It is impossible to talk about Serra without talking about his ill-fated Tilted Arc, a public sculpture commissioned to adorn an ugly plaza in front of a federal building between Lafayette and Centre Streets. When this gargantuan plate of steel was installed in 1981, cutting the plaza like the slash of a knife, it was derided by judges, lawyers, civil servants, politicians, and others who worked in the building. They saw it as a rusty insult. The New York Post stoked the hatred as the art world organized, rallied, signed petitions, staged protests, and authored editorials. The battle was cast in the press as the poor, beleaguered workers versus the rich, snotty art world. In the middle of the night on March 15, 1989, Tilted Arc was dismantled and eventually carted away to a warehouse in Maryland, where it still rests. I still see it in all its invisible glory when I pass the ugly plaza.

Stigma seemed to attach itself to Serra. Indeed, when I reviewed his second full-scale MoMA retrospective in 2007, an excellent bigwig female curator called it “big-dick art.” In one way, it was true, particularly at the Gagosian Gallery, where Serra and Larry Gagosian, these two alpha males, made pharaonic indoor cathedrals of steel. Serra has also left his masculine imprint on MoMA. At the opening dinner of the 2007 survey, the president of its board of trustees mused to a large crowd, “Richard, we built this for you,” referring to the recently renovated building’s horribly overscaled second-floor galleries and space-eating five-story atrium.

None of this changes that Serra was tremendous. You see his work with your whole body. Running your fingers along those red rusting plates, wandering down their swooping lines, you become a walking nerve ending, thrillingly alive.