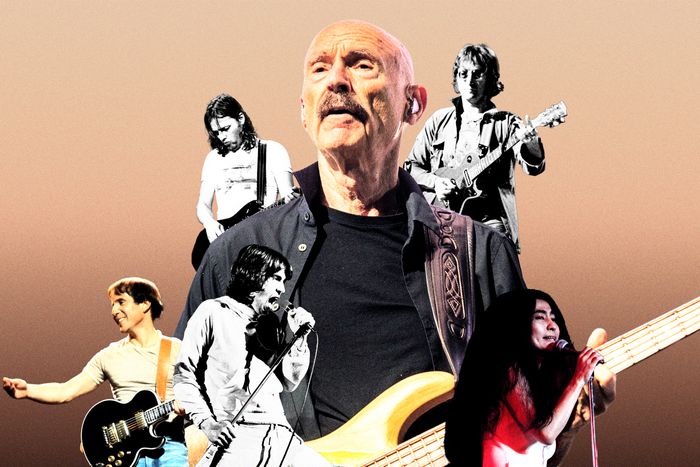

Tony Levin says the word lucky a lot. The bassist, one of the most sought-after session musicians since the early 1970s, doesn’t usually analyze how he ended up in such a fortuitous position. “For all of us who are freelance musicians,” he says, “on a super day we have two great options to choose among, and most days we don’t have any good options.” But come on. Have you seen this guy’s credentials? Peter Gabriel’s band. The Brethren of King Crimson. Lennon, Frampton, Rundgren, Bowie. When Levin hears a piece of music he’s going to play bass on, he turns off the part of his brain that overthinks things and gets straight to work. “It’s a strange process, but it’s a very pleasant one,” he explains. “We find out as we go through life that when you can put the intellectual and analyzing part of your mind to sleep and do something you love doing, those are good hours. They’re not work at all.”

Levin recently wrapped a nationwide tour with BEAT, a group that consists of himself, guitarist Adrian Belew, guitarist Steve Vai, and drummer Danny Carey performing the unbelievably funky music of 1980s King Crimson. (Levin, who often takes photos from his perch onstage, documents each performance with amusing road-diary dispatches that are always worth a read.) To cap off a 2024 that also included the release of a new solo record, Bringing It Down to the Bass, Levin took a spin through his archive to reminisce about the most significant sessions of his career.

Paul Simon, “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” (1975)

The way it got put together as a session was fascinating. I had worked a bit with Paul already, and he tended to use the same technique in the studio. He plays his song and walks over to the keyboard player first. At that time, it was Richard Tee. He plays it with him and works out the piano part. And then Paul walks over to Steve Gadd, the drummer, and does the same thing with him. Then he comes to me, but he sang to me the bass parts he imagined. The bass player in me was interested in those very melodic ideas he had, but I also wanted to ground it and play differently. That’s what he wanted. He wanted me to be myself but to be influenced by his ideas. If you can be bothered to listen to the bass part on that song, it starts out very melodically — I’m not playing the roots. And then in the B section and in the chorus, it goes down to playing very simple and sparse. So I got to be “me” and I got to be Paul. Being around him for a few albums in the studio and hearing those ideas influenced me as a bass player. At its deepest level, my bass playing isn’t just picking the right notes. It’s being the kind of musician who’s aware of what, musically, is best for that situation.

Peter Gabriel, Peter Gabriel (1977)

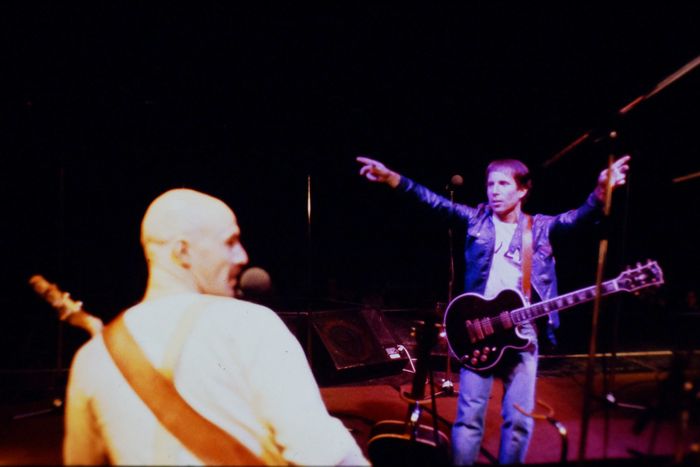

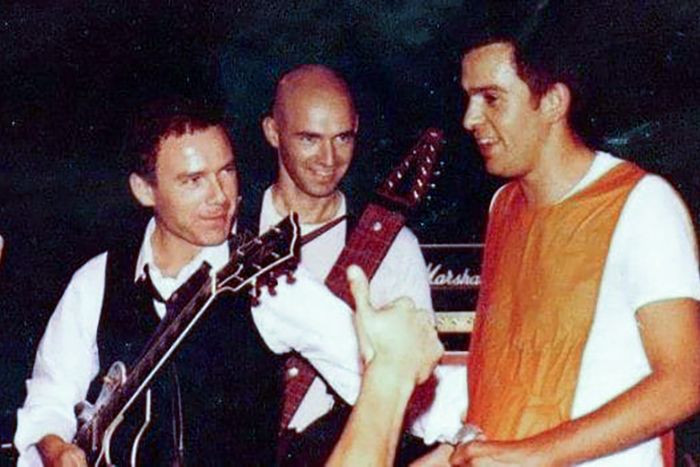

Without question, the most significant session I’ve done in my career. Peter had just left Genesis. I didn’t know who he was or even what Genesis was. I was lucky in the sense that, for one, I got to play with Peter and I’m still in a musical and friendship relationship with the guy. And two, one of the guitarists on that session, Robert Fripp, is the founder of King Crimson, which I subsequently joined. How significant in one’s career — anybody’s career — to make two connections like that, which go on for so many years and involve such music? It was a terrific lineup for Peter Gabriel. The producer, Bob Ezrin, was responsible for my being there, and he had used the same rhythm section for some Alice Cooper and Lou Reed records.

Peter was different from anybody I had heard. The music turned out quite different from Genesis, so even if I had done my homework, I would’ve been surprised and pleased that this was in a whole different direction. He was so energetic, young, and trim. Actually, we were all energetic, young, and trim back then. Soon after, I was on tour with him and saw the other side of Peter. I wouldn’t say Peter is shy, but he’s a quiet, humble, and gentle person. And then I got onstage with him and he unveiled Rael, the Genesis character he goes into. He’s basically a juvenile delinquent who’s out of control. I was like, What the hell is this?

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Double Fantasy (1980)

These took place at the Hit Factory. They were supposed to be a secret. The first day at the sessions, we were instructed by the production team not to tell anybody — even family — what we were doing. They didn’t want the word out, which, of course, was a reasonable request given the artists at hand. On the second day, I got in a taxi and told the driver to take me to the general area of the Hit Factory. And the cabdriver responded, “Oh, that’s where the John Lennon sessions are going on.” I was amazed. I said, “Excuse me, but how did you know that?” And he responded, “Oh, it was on the radio this morning.” So the secret of those sessions didn’t work out so well.

John’s first words to me were “They tell me you’re good. Just don’t play too many notes.” I smiled, knowing that I don’t play too many notes and it wasn’t going to be a problem. I’m very comfortable with his sort of New York, Let’s be direct here, let’s not beat around the bush. So I had a laugh about that. John would, like Paul Simon, play the guitar for all of us at the same time. He wouldn’t walk over me as a bass player. My thoughts were always, He’s playing a John Lennon song. He’s not playing something that sounds like a Beatles song. And then inevitably I’d think, There are 5,000 bass players on the planet who could do a great job at this right now. I have to find the right notes. It’s all there for you. I was very gratified that John seemed to like my bass parts.

We alternated between his and Yoko’s songs. Yoko didn’t play an instrument, so how she communicated her pieces was the exact opposite of John. John could just play it and the musicians knew what to play. Whereas Yoko had to go through it and had an arranger do charts, which weren’t too indicative of what we really ought to play. It was a different adventure finding the style and the way to best do Yoko’s songs. We would do one after the other. On John’s pieces, Yoko would be in the control room helping out with a comment or two or bringing out tea. And then John became the tea boy and went into the control room and kept quiet and let Yoko run her sessions.

Pink Floyd, A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

David Gilmour asked me to play bass on the album after Roger Waters famously left the band, thinking it was the end of them. I wasn’t part of any of the band’s intrigue and was thrilled to enter into the world of trying to play appropriately for a Pink Floyd context but also be somewhat myself. I brought out the Chapman Stick, an instrument I can play as a bass. It’s not the most common instrument, but I use it as one of my regular basses. I found David to be a fascinating guy and a real gentleman — a wonderful person to be with.

Those sessions weren’t exactly hard, but the style of Pink Floyd is very particular. I can remember one instance when I had a long vamp out and I played an extra few notes. I’m not talking about a fast bass riff here; I’m just talking about a couple notes. After the take, when we got together to listen, David smiled and said, “Tony, in Pink Floyd you don’t do that extra couple notes until far later.” I had the right idea, but I did it too quickly. He was silently saying, You don’t know that, but the rest of us do.

The music went down fine. But here’s the kicker: Somewhere only a week or so into the session came up the subject of whether I could tour with them. But the tour was to begin a little bit before the end of a Peter Gabriel tour I was already involved with. So I was exposed to this conundrum not many people have had: Oh, do you want to tour with Pink Floyd for a year and maybe forever? But it would involve missing the last few weeks of a Peter tour I was already committed to. It was one of those big career decisions, perhaps even my biggest, where I went to stay with Peter. I’ve never regretted it, but I’m sure my career path would’ve been different had I spent that next year and a half doing Pink Floyd.

David Bowie, The Next Day (2003)

David Bowie had planned a very secret session because he hadn’t done an album in years and people thought he was retiring. So when I was called for it, the production team told me not to tell anybody. And unlike John and Yoko, this really was a big secret. Even at the studio, in lower Manhattan, they had given the workers two weeks off to ensure they wouldn’t be there.

I had to be working on a Sunday, which was the wedding day of a close friend of mine. I was to be the best man at that wedding. This close friend was a David Bowie fan. Here was my conundrum: What do I tell him? Do I turn down the session to be there for the wedding or do I do the opposite? Should I tell him at all? I was sworn to secrecy by the production team, so it was tricky. The compromise I came up with was I did say no to the Sunday session, but I did the Saturday session, which meant I wasn’t there for the rehearsals of the wedding. And I didn’t tell my friend. I had to be like, “I’m sorry, I can’t be your best man. I can only be there at the wedding.” So how’s that for a cryptic compromise? About a year later, I had, frankly, forgotten about this secret session and the album coming out. But the producer, Tony Visconti, emailed me at midnight of the day it could be spoken about. Immediately, I called my friend and said, “Remember when I couldn’t make the rehearsal dinner? I was doing a David Bowie session. I hope you appreciate that and forgive me for not telling you about it.” He did, thank God.

Anyway, the thrill was being in the studio for an extended period of time. I was playing the songs with David playing keyboards right beside me. He didn’t say much. He let me do what I did. I hadn’t known what a good musician, a good player, he was. He really helped things by his live playing of the keyboard and singing along. So that was a hoot. I’m a photographer who takes a whole lot of photos in the studio. I asked if I could take a photo, and they told me, kindly, “No, you can’t.” The photographer in me kicked myself in the butt, thinking, You should have taken a photo and then asked, so you would have that one picture. Instead of being the bass player who asks first and then doesn’t take the photo. Oh well.

And now, a bonus memory …

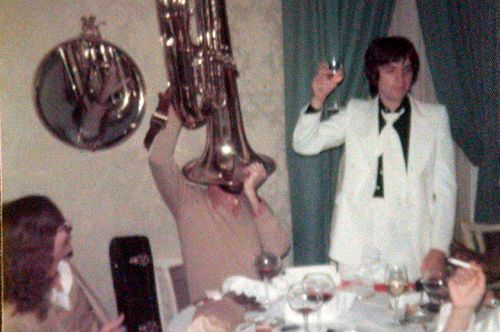

In the 1970s, as a newcomer to New York session playing, I was called to play on a jingle — a one-hour session — for Old Spice. Arriving, I found it was a big band composed of horn players I’d admired for years. They were great jazz players doing whatever sessions came up. Whistling the famous Old Spice theme was Toots Thielemans, the great harmonica player, whistler, and composer of “Bluesette.” Arranging and conducting was none other than Herbie Hancock. I played my simple part, thinking, Tony, you’re not in Rochester anymore.”