The Beautiful Swamp

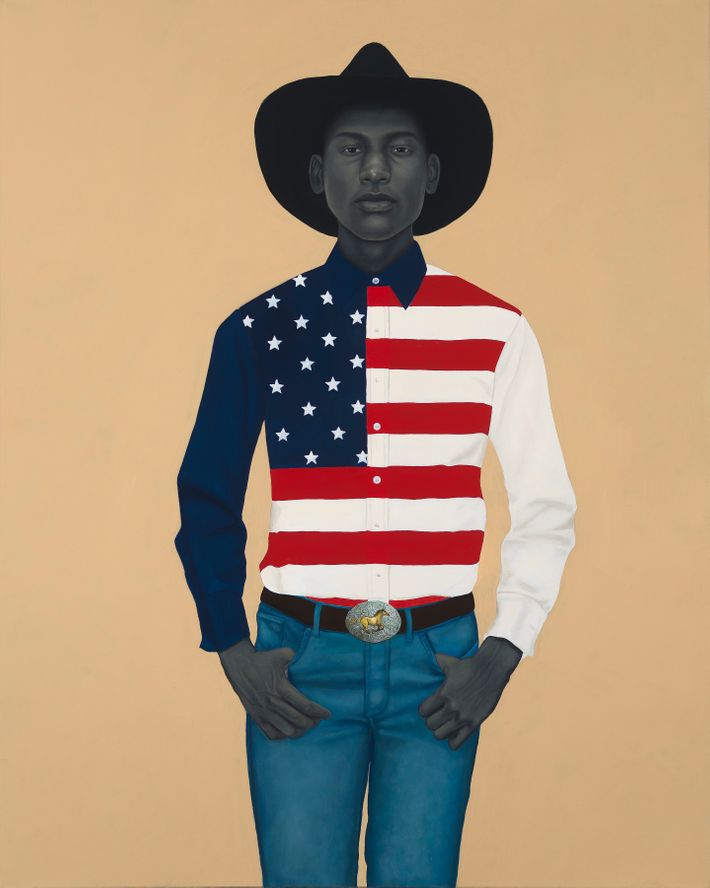

As the art world sees more demands for art to be destroyed, removed, and not made at all, and as economic pressures to simply survive are ratcheted up ever higher, a few newer artists and smaller venues must be named. Among others, Stacy Leigh’s deeply strange nudes at Fortnight Gallery; Nicholas Cueva’s mysterious paintings at the Brooklyn community space Five Myles; Louis Fratino’s weird realism at Thierry Goldberg; Jordan Casteel at Casey Kaplan; Maryam Hoseini’s complex illuminated manuscript-like paintings at Rachel Uffner; Nina Chanel Abney’s grand combinations of Stuart Davis and Jacob Lawrence, at Mary Boone and Jack Shainman (who’s become one of the better galleries in the world); Marcia Marcus’s prescient 1970s paintings at Eric Firestone; the teeny storefront 56 Henry mounted consecutive excellent shows of Cynthia Talmadge, Richard Tinkler, and Kate Shepherd; personal perennial faves shone, including Cary Leibowitz, Lisa Beck, Mira Schor, Keith Mayerson, Julian Lethbridge, Betty Tompkins, Jack Pierson, Ken Tisa, Tabboo, and Ashley Bickerton. Finally a big Obama bravo to painter Amy Sherald, 44, of Baltimore, plucked from almost-obscurity by Michelle Obama to paint her official portrait.

‘Midtown’ at Lever House

“Midtown,” a wildly all-over-the-place, sprawling, soup-to-nuts pop-up show devoted to craft, design, and 100 things in between, was organized primarily by Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn with Michele Maccarone and Paul Johnson. This show crossed an invisible Rubicon — the unspoken but rigid separation the art world still maintains between itself and anything like design. Almost every object here occupied the ever-murky abyss between form, function, art, beauty, and originality. This great clash of sensibilities and styles provided instructive wonder.

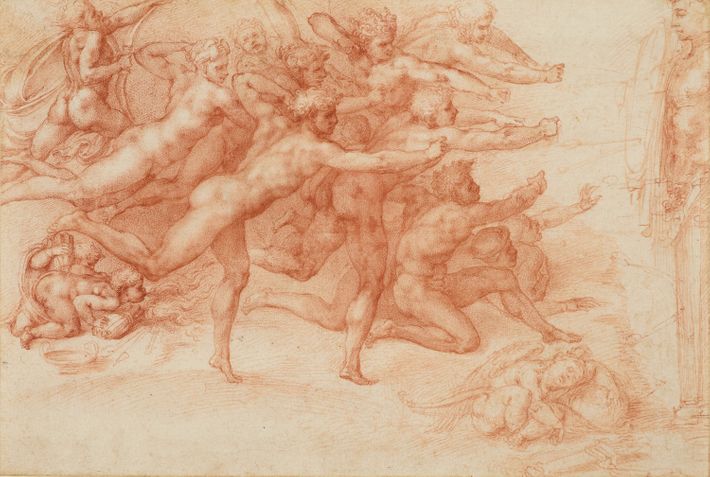

Michelangelo vs. Leonardo

The best lesson in really using and trusting your eye came when the tremendous show of Michelangelo drawings opened at the Met just days before Christie’s auctioned off “a brand-new” Leonardo da Vinci for more than $450 million to an anonymous phone bidder. So was shown the difference between real art history and fake art history. The Michelangelo exhibition showed just how overwhelming the work of the towering Old Masters can be. The fishy Leonardo, heavily repainted, with contested provenance, maybe not by the master at all, was only the triumph of pure marketing over connoisseurship. Christie’s wins the Breaking Faith With Art award of 2017 while the Met delivered up another year of great shows — all put in place by Thomas Campbell before he resigned.

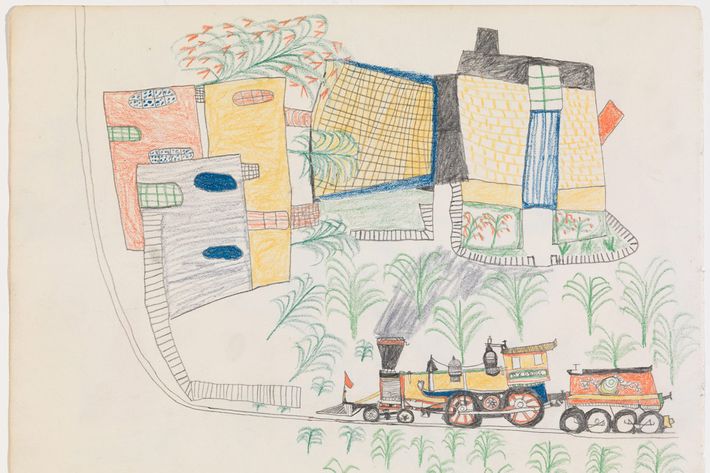

‘Ledger Drawing’ by Bear’s Heart (circa 1875–1878)

In the hubbub of Frieze New York, I was stopped in my tracks by a beautiful prismatic drawing of a train. The fair vanished as I beheld this 1875 picture never seen in any museum and all but lost to history. It depicts a locomotive pulling a string of train cars through fields of corn, past fences, front yards, towns, and buildings. The artist is Bear’s Heart, one of 72 Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa prisoners of war found guilty that year without trial and taken by this train to Fort Marion, in Florida, where all of them were subjected to forced labor. This last look at life outside prison walls and freedom is a hymn to history, to defeat, to death, and a way to console the lost. It’s time to integrate works like this into art museums.

Jonathan Horowitz’s Trump poster and the MAGA hat

Ten days after the Women’s March artist Jonathan Horowitz exhibited a pile of free posters at Petzel Gallery — an altered image of Trump photographed from behind playing golf, in all white except for his red MAGA hat. The sky of the picture was altered to look apocalyptic. The result was a metaphysical journey into this man’s elephantine omnipresence, something half-beast, behemoth. It should hang in every post office for as long as he’s in the White House. Moreover, the MAGA hat may be the closest America has come to producing a modern swastika — something that in countless millions triggers fear, hate, sadness, threat, civil unrest, violence, and in a graphic instant transmits an entire political mind-set. It should be on display at MoMA.

Kara Walker’s ‘Christ’s Entry Into Journalism’

A graphic masterpiece: Kara Walker’s Christ’s Entry Into Journalism is a boat-size drawing on a par with the Met’s enormous Washington Crossing the Delaware. It depicts a psychotic orgy of historical and current American racism, violence, and black resistance. In her signature Sadean Brueghel-Daumier-Goya-Ensor style, Walker depicts more than 100 figures, including the severed head of Trayvon Martin held on a platter, hooded KKK members, a lynching, kids cavorting, Martin Luther King, and more. At the bottom of this hellish vision, a Black Panther figure gives a Black Power salute as he holds the severed head of Donald Trump branded with a swastika on its forehead.

David McDermott and Peter McGough’s ‘Oscar Wilde Temple, 1917, MMXVII’ at the Church of the Village

In a basement chapel of the Church of the Village and the LGBT Community Center, the longtime art-world treasures and collaborative duo David McDermott and Peter McGough created Oscar Wilde Temple, 1917. A small dimly lit mise-en-scène devoted to the tragic last chapter of Wilde’s life: his trials, imprisonment for homosexuality, and death in exile in 1900, at 46. The centerpiece was an elegantly carved realistic wooden figure of Wilde atop a pedestal displaying a plaque painted with the number C.33. This was Wilde’s prison number at Reading Gaol, where he was confined at hard labor, never allowed to speak, and made to sleep in his own feces on a plank inches from the cold stone floor.

The New Museum’s Months of Women

May to September were electric building-filling months at the New Museum, with four standout concurrent solo shows by women artists: the late under-known Italian visionary Carol Rama, the gnarly art of Kaari Upson, the materially complex alchemical sculptures of Elaine Cameron-Weir, and the steamy, seductive portraits of a beautiful community of black dancers and others by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. We must also mention other exceptional museum shows of work by women, including Rei Kawakubo at the Met; Louise Lawler at MoMA; We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 at the Brooklyn Museum; and American visionary Florine Stettheimer at the Jewish Museum. At the Whitney Museum, Laura Owens, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Bunny Rogers, and Willa Nasatir made the first part of year three in the new building as convincing as the two years before that.

Richard Prince’s Disowning of Ivanka

Ten days before the post-inauguration Women’s Marches, the artist Richard Prince enacted his own artistic resistance, trying to hit a Trump where they all live — in the pocketbook. On his Instagram, beneath the commissioned portrait of Ivanka Trump he made in 2014, he wrote “This is not my work. I did not make it. I deny. I denounce. This fake art.” Prince returned the $36,000 he’d been paid and added, “I’ve disowned the work. It is no longer my work … SheNowOwnsAfake. This should not B confused with aesthetics. This is not a gesture. This is an action.” That one-person refusal at the outset of the current shitstorm spoke to how things in the inner life of art are different now.

The Signs, Posters, and Clothing at the Women’s March

On January 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration, the inner upheaval, pain, and anger over electing a charged sexual abuser to the presidency erupted. It took the form of hundreds of Women’s Marches all over the country, composed of tens of millions of people. As powerful as the sheer numbers, the optics of the march were dominated by a multitude of brilliantly creative homemade signs, clothing, buttons, banners, flags and posters. This was a visible barbaric yawp of passion, fury, and incredulity. It was a collective expression of something like need for an ideal of democracy, decency, something not so sick or twisted. This unleashing of creativity told you that the mists of complacency had lifted and that inventive rebellion was already fomenting.

*A version of this article appears in the December 11, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

This article has been updated to reflect the correct spelling of the artist Tabboo.