One day in 1973, the Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto received a phone call from a stylist, who insisted that Yamamoto leave Tokyo immediately to catch a plane for New York. The reason? There was someone on the other side of the world that he had to meet.

Thirteen hours by plane and some time after landing in New York, he arrived at Radio City Music Hall, where David Bowie descended from the ceiling during a show, dressed in Yamamoto’s designs. Almost instantly, Yamamoto felt a connection with Bowie. “I felt like I’d known him forever,” he remembers.

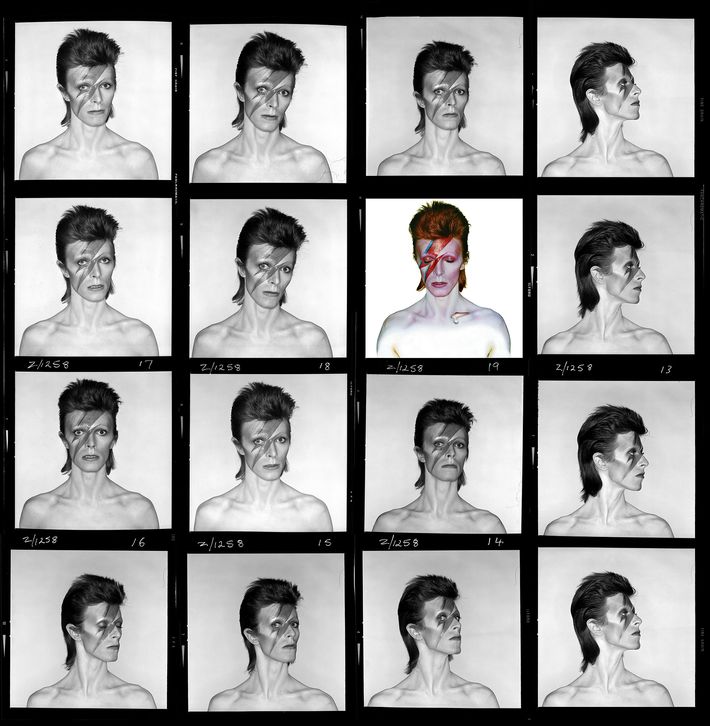

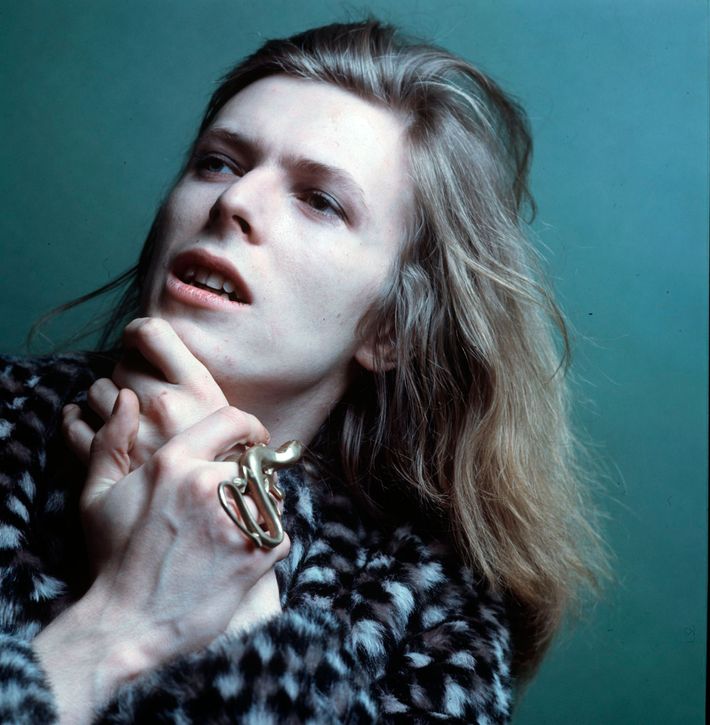

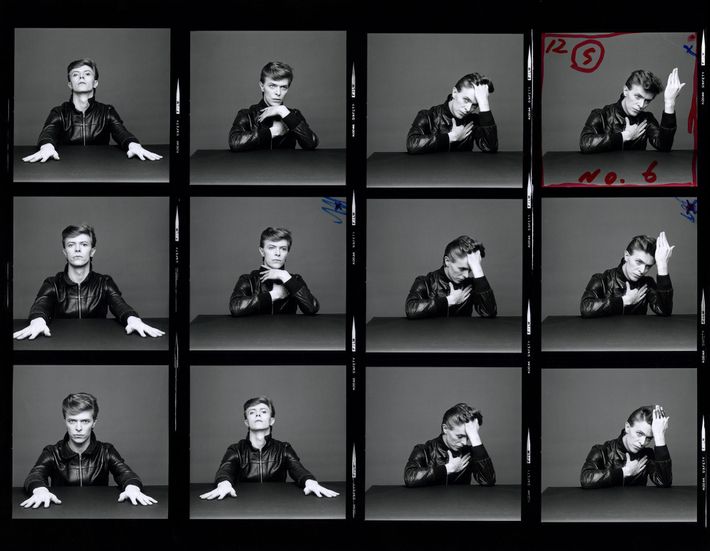

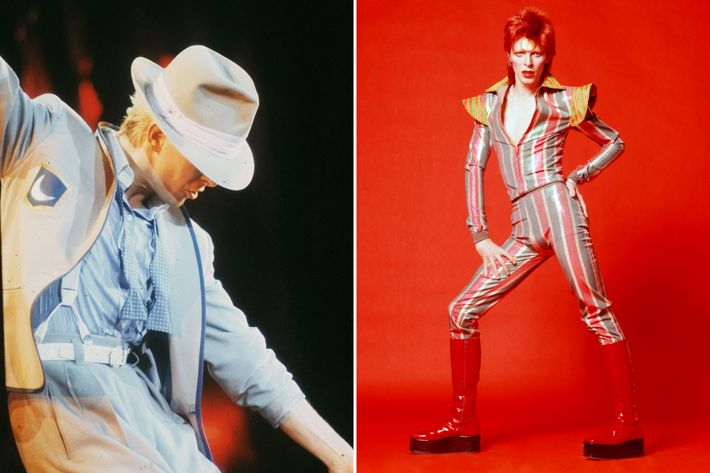

This week, the highly anticipated “David Bowie is” exhibition will open at the Brooklyn Museum. Debuting March 2, the show is organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where it debuted in 2013 and became the most-visited exhibition in the gallery’s history. At the heart of the exhibition are hand-written lyric sheets, drawings, paintings, music videos, television clips, and costumes by the late British designer Freddie Burretti alongside seven costumes that Yamamoto designed for Bowie during his “Ziggy Stardust” and “Aladdin Sane” tours.

Bowie had admired Yamamoto’s work since he made waves as the first Japanese designer to present at London Fashion Week in 1971. His work — heavily influenced by the Japanese concept of Basara, meaning “extravagance, eccentricity, and excess” — fit the essence of Bowie’s developing stage personality. So the singer asked him to design more of his costumes.

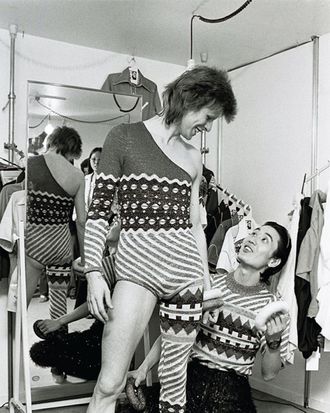

Like Bowie, Yamamoto was uninhibited by the confines of gender in fashion — he designed for no one in particular, although his clothing was, and still is, generally worn by women. Several years of collaboration and countless fittings produced what are remembered today as some of Bowie’s most iconic stage costumes, including the asymmetric knit leotard, the wide-leg vinyl Tokyo Pop jumpsuit, and a white cape, emblazoned with Japanese kanji letters, which Bowie stripped off onstage in 1973 during his “Ziggy Stardust” tour. Just last year, similar Japanese theater icons and Samurai symbols appeared on handbags and dresses in Louis Vuitton’s spring 2018 cruise collection, which Yamamoto was invited to work on with Nicolas Ghesquière.

Ahead of the Brooklyn Museum opening, the Cut spoke with Yamamoto about his memories of Bowie and the Japanese theater techniques that inspired the singer’s legendary performances. Read on for his thoughts below.

On Bowie’s personality: “There was a clear distinction between David ‘onstage’ and David ‘offstage.’ The second he stepped on the stage, there was an immediate shift in energy unlike that of any other artist at the time.”

On his favorite memories of working with Bowie: “I can’t remember exactly when this happened, but David once brought his son Zowie — better known today as Duncan Jones, the film director — with him while he was performing in Japan. That day I was fitting David in his costumes at my studio in Harajuku, and during his fitting, Zowie and my daughter Emma went out to Kiddy Land, a famous toy store nearby. David was always gentle and good-humored; he seemed like a good father.”

On what drew Bowie to his designs: “David was a true vanguard — he was making waves in the musical landscape of the time. His energy resonated with my own desire to venture out into the world. I think David felt that the energy in my designs contributed to his own energy. He knew that when he wore my clothing onstage, he could elicit a strong reaction from the audience.”

On Bowie’s interest in women’s clothing: “Today, lesbian and gay people today are gaining more rights and acceptance, but when I was working with David, that community did not have the same rights. So I found David’s aesthetic and interest in transcending gender boundaries shockingly beautiful.”

On introducing Bowie to hikinuki, a method in Japanese kabuki theatre, of quickly changing costumes onstage: “In the West during the ’70s, there were graphic T-shirts printed with English letters, but none with Japanese characters. So for David, I spelled out his name phonetically in kanji characters on the white cape I designed for him. On stage, he quickly removed the cape, revealing a different outfit underneath. When David did this quick costume change onstage, the reaction from the venue was incredible.”

On his impression of “David Bowie Is”: “When I saw first the exhibition, I felt again what I always knew: that David Bowie was an icon of his time.”

Interview translation by Francisco Andrade and Dr. Nathen Clerici.

“David Bowie is” will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum until July 15. The black-and-white image above, of Yamamoto and Bowie together, is from another show, “Bowie”; the photo is on display and available for purchase until March 23 alongside several other photographs at the Morrison Hotel Gallery in New York, Los Angeles, and Maui.

Scroll below for a preview of the Brooklyn Museum retrospective.