In her home country of Brazil, Tarsila do Amaral is fondly referenced as Tarsila, the woman who led her country’s modernist art movement in the 1920s. Across South America, it’s not unusual to find one of her major works printed on a pair of flip-flops or on a phone case; in Argentina, her most celebrated painting, Abaporu, is as important to Brazil as the Mona Lisa is to France.

This week, Luis Pérez-Oramas, the former curator of Latin American Art at the MoMA, and Stephanie D’Alessandro, the curator of Modern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art are introducing America to an important piece of modern art history with a new exhibition devoted solely to the work of Tarsila. The exhibit, “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil,” focuses on three of Tarsila’s major works: A Negra, Anthropophagy, and Abaporu.

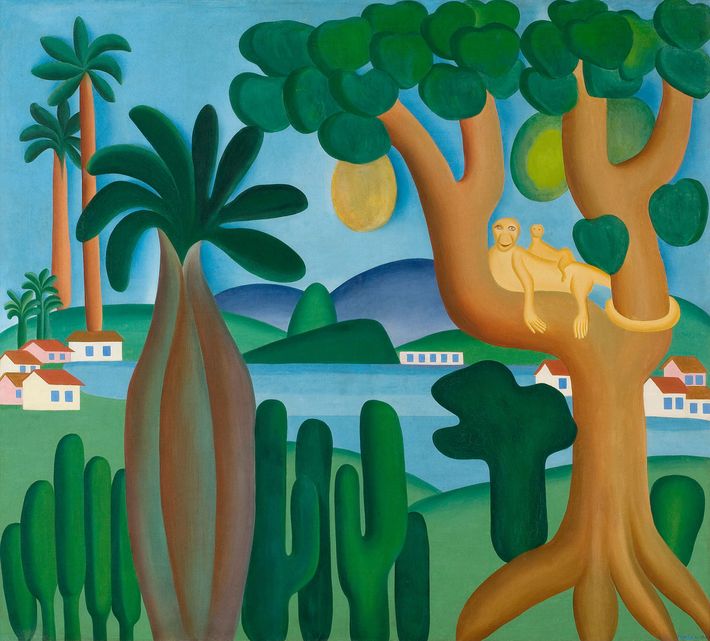

Abaporu is frequently cited as having inspired the artistic movement known as the Anthropophagic (from “anthropophagus,” meaning, “feeding on human flesh”) Movement. As outlined in the Anthropophagic Manifesto, written by Tarsila’s husband Oswald de Andrade, it advocated for “cultural cannibalism,” a style of modern artwork that symbolically “consumed” and transformed the cultural standards of European art to create a new style that was distinctly Brazilian. Tarsila’s work was characterized by landscapes and creatures painted in bright colors once considered tasteless by many in the art world. Her paintings from this period were displayed in her first solo exhibition in Brazil in 1929.

It was not until the 1960s, when Brazil’s Tropicália movement, combining the avant-garde with the popular, flourished in theater, music, and film, that Brazilian culture fully embraced and realized Anthropophagy.

Alongside her paintings are more than 100 drawings, sketchbooks, and photographs that tell the story of Tarsila’s life in Brazil. Many of the subjects in her paintings are renditions of characters from the stories her nannies shared with her as a child, while others depict the nature scenes that surrounded her in São Paulo, and later in Rio de Janeiro.

“Her work stands in for a moment of Brazilian history and culture that people are very proud of,” D’Alessandro told the Cut. “[What] precluded us from being aware of this story, and how many other stories have we also missed?”

“Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” is on view at the MoMA until June 3, 2018.