“Art is everywhere. It’s our way of speaking, dressing; it’s a performance and a means of communication; it’s food, music, dancing,” said artist Hank Willis Thomas. It was one week before the midterms, and he was speaking on a panel at the new Electropositive work space and gallery in Crown Heights, to a crowd of young creative professionals who were nibbling on Middle Eastern snacks. Since Donald Trump became the nominee for president, and especially after his election, there has been an unprecedented sense of mission in the art world that something must change, and that, perhaps, artists could help change it. But can they?

We saw the return of protest art, a once-vital and inspiring idea that had, especially over the Obama years, moved out of the mainstream consciousness as the art world became ever more complacent (and rich). Was all this protest just people in a bubble talking to other like-minded people? Who knows if art can inspire someone away from cynicism to vote, to believe in the possibility of change through our democratic system, hobbled as it is by the interests of big money, and enforced by gerrymandering and voter suppression. Or, and this seems like a bigger, more improbable possibility, could art actually help change a vote?

Thomas feels like artists should not disengage and try to remain somehow pure. “The problem is, we often think that art has to be detached from our life to be influential, and that’s why it’s underappreciated and underfunded,” continued Thomas. “Art and humanity are interconnected. Artists should see themselves as civic leaders. Being realistic has never led to significant change.”

In 2016, Thomas and artist Eric Gottesman, founded the civic art platform For Freedoms, and got some press attention for registering the effort as a super-PAC. They got even more that year for putting up a billboard in Pearl, Mississippi, in which the words “Make America Great Again,” were superimposed over an image taken during “Bloody Sunday” in Selma in 1965. Before the midterms this year, their organization was putting up billboards in every one of the 50 states.

“Is art enough to change society?” Rashid Shabazz, of the group Color of Change, asked Thomas at the Electropositive event, giving voice to the question on everyone’s mind.

Thomas believes so. The “50 State Initiative” included, besides the billboards, exhibitions, educational panels, and town-hall events across the country.

“There’s been a long-running question in the art world about our role within the larger world,” says Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum who co-curated the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 and the Whitney’s Incomplete History of Protest show. “There’s a tendency to see the art world as separate from broader cultural, social, or political worlds, which I think is not helpful or accurate. Particularly with protests against institutions we’ve seen that issues of class, race, gender, and access are vital. Protesters come to us because they see us as part of the world, and hold us to task accordingly. We have greater legitimacy and more importance than we sometimes think we do. We have a responsibility towards the public.”

Our current resurgence of political and protest art addresses issues like gun control, immigration, police brutality, climate change, and women’s rights.

In recent years, a series of protests against art institutions for issues ranging from colonial appropriation (Decolonize this Place) to unethical funding (Nan Goldin against the Sacklers’ opioid empire) has inspired self-reflection within the art world. Complicated cases such as the departure of the politically outspoken president and executive director of the Queens Museum, Laura Raicovich, who was forced out earlier this year reportedly due in part to her activism, reminds us that the people who pay for the art world might not share artists’ values.

“We’re in favor of art organizations being engaged politically,” says New York City cultural commissioner Tom Finkelpearl, “It’s in our mission to let people know about city policies and resources for voters. The kind of issues we talked about today are extremely important issues for all of New York. Art is political and reflects society. The synagogue shooting isn’t a Jewish people issue; it is a white supremacy issue, and so is the Charleston shooting. Art has to react to that — we have to think about what can be done through art. Art organizations have to focus on is what they can do really well — storytelling, the emotional element, the poetic.”

As preelection tension and vitriolic propaganda grew this week, Finkelpearl convened cultural leaders to BRIC for a summit on immigration focused on radical activism and the creation of sanctuary spaces within art institutions. Diya Vij from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs opened the event with an acknowledgement of the ancestral land of the Lenape people; public art organization No Longer Empty’s Raquel de Anda closed with remarks on terrorist acts committed by white supremacists and the need to take more risks in challenging power structures. The four-hour event, attended by representatives of institutions from the Met to Mark Morris and the Bronx Children’s Museum, featured presentations by community-activist art groups, immigration lawyers, and artists; it encouraged institutions to rethink their role in society, and to support and protect immigrant workers and artists.

For Freedoms’s mission rests on the belief that all art is political. Joseph Beuys established the idea of the “social artist” deeply engaged with the political system. In the ’80s, the collectives ACT-UP and Gran Fury used art to spread AIDS awareness with radical tactics and visual campaigns. Recently, artists such as Theaster Gates and Carrie Mae Weems have been involved in community activism and electoral campaigning. Sometimes looking back at history, it can be difficult to measure the effects of these efforts. There is something particularly tragic in considering the anti-Hitler, antiwar art of the Weimar era and knowing how that turned out. But the recent David Wojnarowicz retrospective at the Whitney could leave you feeling more hopeful and inspired.

Before Trump, “many communities were apathetic and self-involved,” says Jeffrey Deitch, who hosted the nonprofit Downtown for Democracy’s Protest Factory, a series of political art events, in the week before the election, “but I feel strongly that it’s no longer the time to do nothing. You have to be very engaged with what’s going on, even though most people in this country are not — people are more engaged with the football game than in the extreme political atmosphere. But everyone should be active. These are not normal times.”

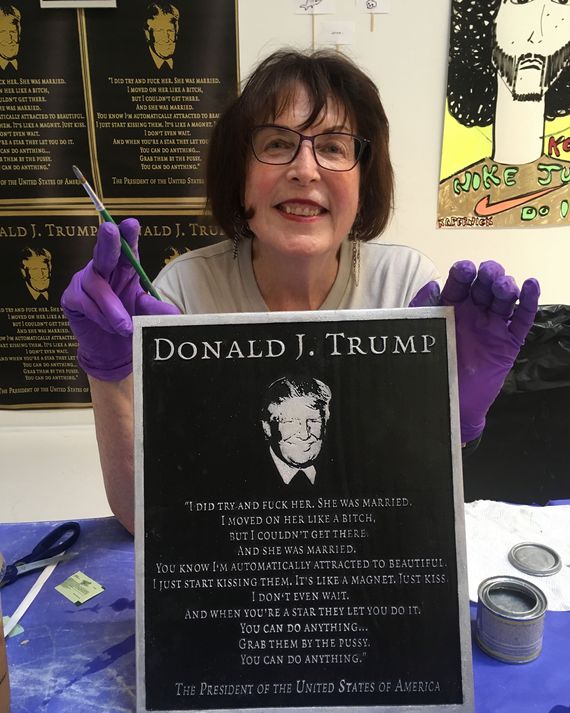

At the Protest Factory opening last Wednesday, Jeffrey Beebe’s colossal Trump Rat greeted the art world’s movers and shakers. Nan Goldin sold P.A.I.N. merchandise addressing the opioid epidemic; Richard Prince offered T-shirts designed with Supreme; Marilyn Minter sat at a table crafting her $2,000 Trump plaques; Richard Hell signed T-shirts; Ryan McGinley took Polaroids. All proceeds went to Downtown for Democracy’s election efforts, which don’t end with the midterms

Many have given up symbolic activity that seems to only echo through the social-media bubbles of the like-minded to focus on concrete acts like canvassing, voting, and raising funds for candidates. As political campaigns flood the country’s screens and billboards, art-world activists are filling buses with voters, installing polling stations in their galleries, dedicating their spaces to political organizations, organizing rallies, and working with community organizations, schools, and prisons.

In a move toward hands-on voter registration, Swing Left also partnered with Downtown for Democracy and the Los Angeles–based Artists for Democracy for two “art world” days of action on November 4 and 5. New York and Los Angeles galleries — including Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, Greene Naftali, Night Gallery, and Blum & Poe, as well as artists Carol Bove and Gordon Terry — helped facilitate canvassing events in swing districts. The Hammer Museum, Brooklyn Museum, and MassMoca are some of the institutions that have set up voting stations. At MOCA, now led by Klaus Biesenbach, Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Questions) was reinstalled in partnership with For Freedoms and a series of voter-registration initiatives.

A crucial channel for recent protest movements, of course, has been social media. Instagram in particular has been a major focus and a medium for celebrity endorsements. Power to the Women’s #Voteperiod campaign was released on Instagram and at Austin City Limits, along with a voter-registration drive. Shot by Melodie McDaniel, Sophie Elgort, Shaniqwa Jarvis, Petra Collins, Danielle Levitt, and Collier Schorr, the images portray young American women in candid settings, juxtaposed with bold graphics imploring them to VOTE NOW, and were inspired by artist Marlene McCarty’s work with Gran Fury and ACT-UP.

While some initiatives, such as For Freedoms, are ostensibly nonpartisan, others endorse specific candidates and campaigns. Jack Shainman, who has built a reputation for championing a diverse array of artists whose work is often political, organized the True Blue Benefit at his Kinderhook, New York, art space the School on September 15. It involved a rally for the Dreamers, a protest at Republican congressman John Faso’s home, and a silent auction.

After Trump’s inauguration, Shainman received death threats for raising Dread Scott’s A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday flag, part of For Freedom’s inaugural exhibition, as protesters marched against police brutality and the killing of African-American men like Philando Castile and Alton Sterling. The gallery ultimately removed the flag from the façade in July 2016 after the landlord threatened legal action.

“What I can do is elicit dialogue and conversation,” says Shainman. “I’m not saying we can change anything, but we do create a dialogue. But when I hear on NPR about people who voted for Trump, I don’t know that the dialogue is making a difference, because there’s no common sense. I don’t know those people, I don’t understand them.”

New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz, like so many in the art world, has taken his activism to his Instagram followers. He cites another good that comes from doing so: “It aligns us with love.” When he posts — and on the eve of the midterms, he excavated a meme he made of Trump wearing a “Make America Hate Again” hat, he feels less hopeless. “For whole long minutes, it takes me out of the foulness,” he says.

And he’ll keep fighting that fight, come blue wave or red swamp.