Hope and change. Yes we can. It gets better. These were the slogans of the Obama era, and they were felt not just in politics, but across a vast swath of American life. The result was a subgenre we are calling Obamacore — the earnest, optimistic, occasionally genius, and often cringeworthy pop culture of the period from 2008 to 2016.

Obamacore is not just anything that was popular during Barack Obama’s presidency. (Breaking Bad, Adele, and The Hunger Games are not on the list.) And it’s not quite the same thing as millennial cringe (calling dogs “doggo,” knowing your Hogwarts house). What it was are these 100 cultural artifacts, all of which — the good and the bad — best defined this particular Zeitgeist. The list is not exhaustive: We could have named hundreds more (sorry, “Cups” song), and readers surely can, too.

The story of Obamacore has three chapters. The first covers 2009 to 2012, Obama’s first term. The second covers 2013 to 2015, the high summer of Obamacore. The third and shortest covers 2016 (as well as one project from the year prior) and the birth of Obamacore’s ill-fated sibling, Hillarycore. In the interest of spreading the love, we decided that an individual artist could only appear once per chapter. To keep things interesting, we also ruled ineligible any TV appearances by an actual political figure. Obama eating noodles with Anthony Bourdain, Joe Biden’s cameos in Parks and Recreation, Hillary Clinton popping up on Broad City — all too obvious!

So put your hands up, you’re reading this list, the butterflies fly away. (Watching the GIFs like yeah, clicking the links like yeah.) Gather round, you grumpy cats and yas queens: You know it’s gonna be okay.

2009–2012

I. The

George W. Bush is out of office, replaced by the nation's first Black president. Has history ended? It is a time of bubbling optimism, unthreatening politics, and the first shoots of a distinctly millennial online culture.

.

Core Text: Glee

Premiering in May 2009, four months after the inauguration, Glee was a cultural bridge between the Bush and Obama eras. The series was sold on co-creator Ryan Murphy’s trademark snark; the first line spoken in the pilot was a waterboarding joke. But as time went on — and, if you subscribe to the “three Glees” theory, under the influence of another co-creator, Ian Brennan — the show ushered in the wider cultural shift toward sensitivity and inclusion. (Onscreen, at least.) Dan Savage may have created the It Gets Better Project, an anti-bullying movement to protect queer kids, but Glee’s Kurt Hummel soon became its avatar, actor Chris Colfer assuming the beatific mien of a Renaissance martyr. Throw in the hold the cast’s peppy pop covers had over the Billboard charts, and there is a case that Glee was the most influential TV show of the early Obama era.

.

Anthem: “I Gotta Feeling,” by the Black Eyed Peas

The rare Americans to become less socially aware between the Clinton and Obama administrations, the Black Eyed Peas by June 2009 had long since abandoned their backpack-rap origins to become purveyors of the stupidest pop music ever recorded. But “I Gotta Feeling” was a lightning-strike moment — four minutes and 49 seconds that embodied the empty-headed optimism of the early Obama era. (Will.i.am has claimed he was inspired to write the song after witnessing the inauguration, though other primary sources tell a different story.)

.

Mascot: Bacon

Maybe it was a recession-era “back to basics” mentality. Maybe it was the election of America’s first nerd president. Either way, the turn of the decade saw the revival of a self-consciously unfussy masculinity, and nothing was more self-consciously unfussy than bacon, the unofficial foodstuff of Obama’s first term. Bacon was manly in an unthreatening, apolitical way, embraced by role models as diverse as Ron Swanson and James Deen. Bacon was viral, not only in the swine-flu sense, but also as a key ingredient in internet-ready creations like the KFC Double Down and Cara Delevingne’s foot.

.

Catchphrase: “Shit [X] Says”

When Justin Halpern launched the Twitter account @ShitMyDadSays in August 2009, he didn’t just land a book deal and CBS sitcom. He also created one of the most viral sentence structures of the coming decade. 2012’s spate of “Shit [Xs] Say” videos underlined the burgeoning sense that identity and behavior were inextricably linked. The first wave of these jokes often incorporated gentle self-mockery from the bourgeoisie. The second, exemplified by Francesca Ramsey’s “Shit White Girls Say … to Black Girls,” turned the gaze around. White people discovered they did not own subjectivity.

.

The Timeline

The “You Make My Dreams” scene in 500 Days of Summer

Here we see the idealized fantasy life of the white Obamacore acolyte of the late aughts, a twee dreamworld of joy and possibility that could only be accessed by sleeping with Zooey Deschanel. The sweater-vest-and-tie combo sported by Joseph Gordon-Levitt in this July 2009 scene retained a stranglehold on this demographic’s fashion sense for the next five years.

Modern Family

The premise of the Modern Family pilot was that American families looked different in September 2009 than they did in the age of Ozzie and Harriet. Families had gay people in them now. Families were interracial. Generational divides were blurred. But the fundamental concept, always contained within the safe and affirming structure of the network sitcom, was that their differences meant less than their shared love — even when they were perpetually sniping at each other. Modern Family was about seeing differences, but then folding them into the presumption of a bigger, more abstract sense that everyone was in it together.

Ke$ha’s “Tik Tok”

Whether you call it “turbo-pop” or “recession pop,” the turn of the decade was marked by EDM-influenced bangers extolling the virtues of living only for the ubiquitous “tonight.” Few exemplified the coming Millennial hegemony more than Ke$ha’s “Tik Tok,” the first No. 1 of the 2010s. Auto-Tuned out the wazoo and featuring a manner of white-girl rapping unlistenable to anyone over 30, “Tik Tok” defied the prevailing roboticism of the pop charts through sheer force of personality. Her lines about brushing her teeth with a bottle of Jack were jokes. Her DGAF attitude wasn’t.

Conan’s Tonight Show good-bye speech

Seven months after ceding The Tonight Show hosting chair to Conan O’Brien, NBC and Jay Leno had second thoughts. Per ratings, audiences didn’t want O’Brien’s brand of alt-comedy to lull them to sleep at night; they preferred the ambient sounds of Leno asking, “Have you seen this?” The network’s solution — giving the 11:30 p.m. time slot to Leno’s new talk show, The Jay Leno Show — inadvertently kicked off an epilogue to the famed late-night wars. O’Brien refused to budge, instead accepting a $45 million contract buyout before slamming NBC mercilessly during his handful of remaining shows. But during his final Tonight Show broadcast in January 2010, O’Brien dropped his snark and delivered a sincere, oft-quoted signoff. “Please do not be cynical,” he urged young viewers. “Nobody in life gets exactly what they thought they were going to get, but if you work really hard and you’re kind, amazing things will happen.” The vaguely hopeful message mirrored the tone of Democratic Party assurances in the years following the 2008 recession: America is a meritocracy, except when it isn’t.

Kathryn Bigelow vs. James Cameron

Kathryn Bigelow making history in February 2010 as the first woman to win Best Director for The Hurt Locker, a movie about the cruel impact of the American military-industrial complex on the country’s troops that also won Best Picture? That’s a girl-power hat trick, and it was only sweeter since Bigelow won over her ex James Cameron. There was a tidy narrative here, of a woman triumphing over her past and joining a boys’ club with the kind of movie we expect men to make about war, death, and empire. But people seemed to miss that The Hurt Locker had a sharply critical take on how American machismo, once entangled with conflict, can’t break apart from it — including Bigelow herself, who after this film would make 2012’s rah-rah-patriotism, torture-vindicating Zero Dark Thirty.

Novelty accounts that got book deals

Did we really have it that easy? A Twitter, Tumblr, or hell, even a WordPress with the right type of infinitely mine-able gimmick could net you a book deal that would let your brand live forever on tables at Urban Outfitters. While not every novelty account went hardcover (sorry, “Lesbians who look like Justin Bieber”), plenty still did, from “Stuff White People Like” to “Guy In Your MFA” to “Hipster Puppies.” The most popular of these, the aforementioned “Sh*t My Dad Says,” snowballed from a book deal in May 2010 into a CBS sitcom starring William Shatner as the titular dad. It was canceled after one season.

Kanye West’s Rosewood movement

In the summer of 2010 — approaching his Jesus year, on the rebound from insulting Taylor Swift and annoying Obama — Ye shifted gears, embarking on a besuited image-reform campaign that invoked the 1923 massacre in Rosewood, Florida. “That’s the Rosewood mentality,” the rapper, producer, and G.O.O.D. Music founder told Power 105.1’s DJ Clue in an interview, “affluence, like, not cursing loud in public, pulling out chairs for your lady, opening up doors …” Notable artifacts from the movement that died when Ye met 2 Chainz and Travis Scott include cocky radio freestyles mining tracks in the works (“This game you could never win / ’Cause they love you then they hate you then they love you again”) and a cozy cabaret night with John Legend, whose friendship Ye would renounce further along into his firebrand journey.

Nicki Minaj’s “Monster” verse

“Pull up in the monster, automobile gangsta …” There’s a fair chance you know every word to the Nicki Minaj verse on Ye’s October 2010 song “Monster,” the lyrics-that-launched-1,000-ships of what’s turned out to be a lucrative career in upstaging people on their own songs. “Monster” is a tentpole of a time of luxe-rap maximalism, of star-studded posse cuts and sky-high ambition. The gladiatorial state of an industry where only a few women were allowed to prosper at a time animates the verse, whose Willy Wonka Tonka truck pulls a hit-and-run on Lil’ Kim on the ride in: “Just killed another career, it’s a mild day.” Minaj infiltrated commercial rap’s boys’ club by force of virtuosity and ego.

Louis C.K. on Marc Maron’s WTF

Subsequent events have made it uncomfortable to acknowledge the cultural influence wielded by Louis C.K. during the Obama era. But to some people living before 2017, he was the closest thing to Dylan in the ’60s. In the spring of 2009, C.K.’s six-month-old Conan appearance titled “Everything’s Amazing and Nobody Is Happy” went viral, confirming his reputation as a philosopher-bard with a unique handle on the absurdities of modern life. The next year brought FX’s Louie, a semi-autobiographical dramedy that became the decade’s most-imitated TV show. But the high-water mark of the C.K. project was his October 2010 appearance on WTF With Marc Maron, which Slate declared the greatest podcast episode ever. The setup: C.K. as the auteur in his pomp; Maron the old friend who’d been left behind. Their resulting conversation felt like the model of new masculinity, especially when C.K. teared up talking about his daughter’s birth. As C.K.’s sexual-harassment scandal later revealed, though, this image of unfiltered authenticity was its own kind of shield.

Katy Perry’s “Firework”

Of the five separate No. 1 hits from Katy Perry’s Teenage Dream album, three became timeless pop classics. (The other two are “E.T.” and “Last Friday Night.”) The most timely was “Firework,” a soaring inspirational dance track whose earnestness was potent enough to break through even the most hardened defenses. The October 2010 song became so identified with Obama-era optimism that, two weeks after January 6, Joe Biden brought Perry out to administer the soothing balm of “Firework” one more time.

The Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear

In October 2010, 215,000 people gathered in Washington, D.C., to attend a rally co-hosted by America’s premier political pundits who’d insist they were actually comedians when challenged, Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. According to Stewart, the goal was to remind the “70 percent to 80 percent” of rational thinkers in America that most of the country’s political discourse was fueled by a vocal minority of extremists. For Colbert, who hosted The Colbert Report in character as a right-wing extremist, the goal was to “keep fear alive.” In 2020, to mark the ten-year anniversary of the event, Stewart went on Colbert’s The Late Show to reflect on its legacy. Fear, he told the host, had won in a “shutout.”

Humans of New York and High Maintenance

A very intentional and specific strain of humanism runs through Branton Stanton’s “Humans of New York,” a photo blog created in 2010, and Ben Sinclair and Katja Blichfeld’s High Maintenance, a web series that debuted in 2012. Both aimed to depict the rich and colorful tapestry of life in New York City by honing in on the individual strands rather than the big picture. High Maintenance freezes in amber two moments of the Obama years: when privileged Williamsburg hipsters (and creators) grew up, took jobs in media, and got marriedpartnered; while “Humans of New York” and its massive popularity reflected the years’ increased focus on diversity, hyper-sincerity, bumper-sticker-coexistence, and digitally performed Upworthy-esque empathy. Both projects quickly grew from DIY to mainstream, with High Maintenance jumping to HBO in 2016 and “Humans of New York” making it to the White House after spawning countless imitators. Now, every town is Humans Of-ified.

Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way”

When confronted with a pop star more interested in appealing to the male gays than the male gaze, numerous observers concluded Lady Gaga must naturally be a trans woman. The artist brushed off the rumor — “Would that be so terrible?” — and for the lead single of her 2011 album, she threw out her usual arcane symbolism for an ecstatic declaration of acceptance: “No matter gay, straight, or bi / Lesbian, transgender life / I’m on the right track, baby, I was born to survive.” Almost instantaneously, “Born This Way” became the decade’s defining queer anthem.

Stomp-and-holler bands

As pop became increasingly robotic in the late 2000s, an international contingent of folkies spurred a new roots revival. Slumming posh boys out of London like Mumford & Sons, suspender-sporting Coloradans like the Lumineers, harmonizing Icelanders like Of Monsters and Men — all sought authenticity in Depression aesthetics and cathartic group sing-alongs. There were beards, banjos, and drumbeats that made them sound like a vanguard for the People’s Republic of Instagram. Normies called them hipsters, but real hipsters usually hated them. That they were all ultimately selling simplicity and comfort can be summed up, as Summer Anne Burton noted, by the fact that the movement was bookended by two different songs called “Home”: one by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros in 2009, the other by Phillip Phillips in 2012.

Drake YOLOs

It speaks to the core of Take Care Drake that “The Motto,” the lustful October 2011 hit with a diabolically infectious “fuck it” energy, wasn’t quite the biggest song on the album. “Headlines” did better, but the adage from “The Motto” — “You only live once” — percolated for years. Back in Karmaloop days, before podcast doms made everything about subjugation, men twisted to impress but still fit in. The root idea of “YOLO” was swashbuckling through the chaos of a night with the bluster of Thor and the luck of Loki. But as most people aren’t Norse deities, or even superstar millionaires, the phrase came to christen its fair share of ill-fated antics.

Internet Boyfriends

In the parlance of the time: not all men. In the middle of the Obama-era gender wars, a few famous men stood apart as avatars of positive maleness. The model for the Internet Boyfriend was set by Ryan Gosling — or, rather, the version of Gosling seen in the Tumblr account Fuck Yeah Ryan Gosling in 2008. From here, we got the “Hey Girl” meme, which received a feminist remix from Danielle Henderson three years later. Approachable, sensitive, and endowed with vaguely progressive politics, Internet Boyfriends spread from Tumblr to the rest of the internet over the next few years. Mostly, they were actors, but there were also porn stars, French economists, even the Pope. Sometimes, the Internet Boyfriend title was backed up by actual actions these men had taken; just as often, they were merely blank slates upon which audiences could project their fantasies.

Undercuts

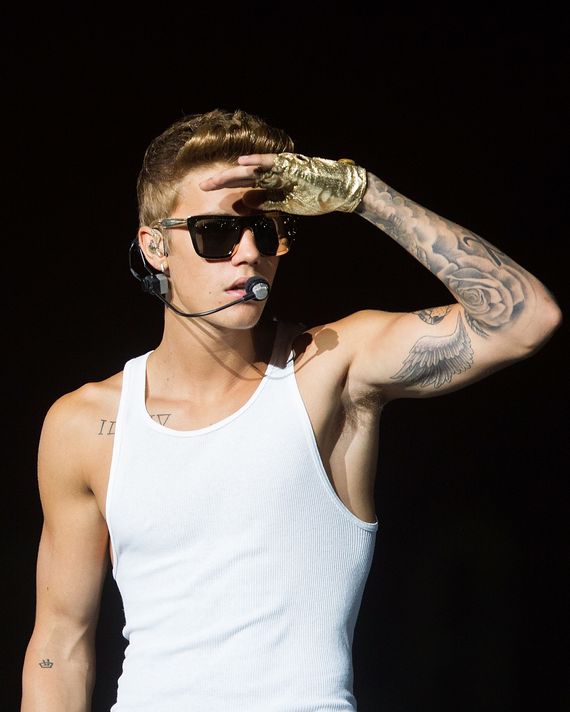

Around 2011, hair began to disappear from the sides of American heads. The undercut took four specific, yet interrelated, forms. First was the so-called “Hitler Youth” cut: buzzed temples and a slicked-back top, seen on Arcade Fire’s Win Butler and Michael Pitt on Boardwalk Empire. (It was later reclaimed by white supremacists.) The second was a Lynchian variation, a pompadour sported by Justin Bieber and the members of One Direction; the third a bleached version of the second, which became a telltale sign a celebrity was about to culturally appropriate. The fourth was most closely tied to this specific cultural moment: a long mane with one or both sides shaved, identified with Cassie, Skrillex, and Rihanna, among others. Experts pegged the trend to the voguish interest in clean lines and trim silhouettes. It also represented a radical break from the immediate past. Small wonder it appealed to DJs, grown-up teenyboppers, and fascists alike.

tUnE-yArDs’ Whokill

When the second album from Oakland indie-folk troubadour Merrill Garbus topped the Village Voice’s Pazz and Jop critics’ poll for 2011, Chuck Klosterman wondered if Garbus’s “singular claim to fame will be future people saying things like, ‘Hey, remember that one winter when we all thought tUnE-yArDs was supposed to be brilliant?’” Klosterman was being condescending and misogynist, but he wasn’t entirely wrong. Whokill is indeed a time capsule of the early 2010s. Its lo-fi sound, full of ukulele and tape loops, fit squarely in the era’s analog ideals. From the barbaric yawp of Garbus’s vocals to the war paint she wore onstage, its unabashed primitivism read as authentic to the indie audience of the day. All this was accompanied by an unapologetically political message through lyrics about police violence, sexual power, and gentrification. In the ’90s, you would have called this “conscious” music, but what’s most striking about Whokill now is its very lack of same. A decade later, an artist with Garbus’s political sensibilities would be savvy enough to hire more non-white dancers and would probably not release a song called “Gangsta.” The ’10s were marked by white liberals’ rising racial consciousness, mirrored in turn by a rising self-consciousness. In Garbus’s unfiltered art-student energy, tUnE-yArDs was a vision of what it looked like before that self-consciousness kicked in.

Cheryl Strayed comes out as Dear Sugar

In March 2010, Cheryl Strayed anonymously took over the Rumpus’s advice column, Dear Sugar, from her friend Steven Almond. Initial entries were in a lighter key; she was warm, profane, and unafraid of the messy bits. As her readers’ parasocial attachment grew, their questions became more urgent and existential in their dimensions. Sometimes there were confessions of sexual kinks or letters of unbearable loss, and yet Sugar seemed able to hold it, like a little miracle. The column became a sensation, and the biographical scraps she gave — a former heroin addict, published writer, grieving daughter — made her identity the source of endless speculation. After almost two years, she had a “coming out” party at Housing Works in New York on Valentine’s Day in 2012, just a month before the release of Wild, her memoir about hiking the Pacific Crest Trail solo. What was once small and indie soon became big and branded: an Oprah’s Book Club pick, a movie starring Reese Witherspoon, a play, a TV show, and a podcast. But at one point, we were all just her little sweet peas.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson goes to Congress

Tyson’s March 2012 Senate testimony, where he argued for the wonders of space exploration, secured the paternal astrophysicist’s standing as supreme leader of experts. It was the apotheosis of work he had been doing elsewhere: PBS specials, talking-head spots, his own podcast, and, notoriously, extended stints on Twitter where he’d poke holes in movies. At the time, his brand of nerdy pedantism was charming, even celebrated, to a point where he was elevated as yet another new model of masculinity. It had not yet been politicized by the culture wars of the COVID-19 pandemic — nor complicated by the sexual-misconduct charges Tyson would weather several years later.

Girls discourse

Even before it premiered in April 2012, Girls was a sociopolitical tinderbox. Was the HBO dramedy a critique of millennial narcissism or an embodiment of it? Was it nepotism to hire the drummer from Bad Company’s daughter? Weren’t they actually satirizing people with zero Black friends? Distance would bring consensus on these questions (the former, kinda, and yes, respectively), but in the meantime, the discourse had the capacity to drive anyone with a Twitter account temporarily insane. By Girls’s second season, creator Lena Dunham was responding to online critiques through the series, sometimes by addressing them in the most ham-fisted way possible (like bringing in Donald Glover to play a Black Republican), sometimes by thumbing her nose at the haters (as in the episode where Dunham’s Hannah slept with Patrick Wilson). What united the pro- and anti-Girls camps was a conviction that there were real stakes in the matter and that the show represented something larger than itself.

Scandal

Scandal premiered as a late-season entry in April 2012 on ABC running for just seven episodes, which was just enough time to find its foothold. Here was Olivia Pope, played by Kerry Washington, a Beltway fixer who was having an affair with a sitting Republican president. If Grey’s Anatomy introduced Shonda Rhimes as a TV hitmaker, then Scandal established her ability to shift the racial paradigm around who could lead a primetime network drama. Along with How to Get Away with Murder, the trifecta formed the network’s Thank Goodness It’s Thursday lineup in 2014. Scandal introduced its own Twitter-friendly lexicon (white hats, gladiators in suits, etc.) to create delirious watercooler television, mixing the sex-in-the–Oval Office romance between Olivia and Fitz (Tony Goldwyn) with bonkers plotlines and rageful ratatat monologues. Politics and race followed its own logic. The same way a Republican president might pass comprehensive gun control, race was its own fantasy: The most powerful man in the world was on his knees for Olivia Pope.

The Shawarma scene in The Avengers

Superheroes had cracked jokes before; what was fresh about the Marvel Cinematic Universe was the knowing quality with which they did it. Case in point, the post-credits scene in May 2012’s The Avengers, in which our heroes celebrate saving the world by chomping down on some shawarma. A callback to an ad-lib from Robert Downey Jr., the literal last-minute addition (it was shot after the film’s red-carpet premiere) heralded a looser, more approachable epoch for superhero cinema, one that didn’t take itself so seriously. The fun of the Avengers was not that they were larger than life, but that they were life-size — just some colleagues grabbing a bite after work.

The Borowitz Report

The long-running humor blog from Fresh Prince of Bel-Air creator Andy Borowitz, acquired by The New Yorker in July 2012, offers a historical record of what upscale liberals found funny at the time: jokes about the NRA, low-stakes fantasies of political violence, and above all, their own intellectual, geographical, and moral superiority. Borowitz’s contemporary critics accurately pegged the blog’s overall sense of smugness. With hindsight, what is even more apparent is its overwhelming complacency.

Viral pets

On the internet, animals are reliable currency: easy to love, easy to meme. This quality, combined with a new widespread pursuit of social-media clout, led to the production of numerous famous pets: Grumpy Cat, Lil Bub, Maru, Jiffpom, and so on. The minor-celebrity creatures (Grumpy Cat became the official spokescat of Friskies in September 2013) fit the digital aesthetic of the era. This was a time when the internet was earnest and aggressively playful, insisting on bright pastel colors and start-up names ending with “-ly” to support the feeling of a welcoming space. The pets themselves didn’t always seem happy to be there.

Cloud Atlas

“I don’t see color,” movie-fied. The October 2012 big-budget-indie gamble from co-directors and co-writers the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer was an ambitious adaptation of David Mitchell’s sprawling novel, with a racially and ethnically diverse cast tackling a racially and ethnically diverse ensemble of characters living in various times and locations. The project’s underlying “we’re all the same underneath” ideology was emblematic of the breaking-down-barriers approach of this time, and that earnest embrace of identity was mirrored in director Lana Wachowski publicly coming out as a trans woman during the film’s promotion. But all that well-intentioned sincerity couldn’t quite make up for the fact that Cloud Atlas’ particular vision of inclusivity, in which any race could play any race, presented yellowface as no big deal. The movie has overcome that initially polarized critical reaction to become a cult classic, but its inherent contradictions reflect so many of the era’s limits of representation.

.

Swan Song: Anthony Bourdain’s monologue in the No Reservations finale

The late Anthony Bourdain has been eulogized as many things: global ambassador, the last curious man, rare noble white guy. No Reservations, his mid-career television work, was the vessel that saw Bourdain come into his own as a public figure championing a borderless world. The show ended in November 2012 — the halfway point of the Obama era — with a closing Bourdainean monologue that bottled the spirit of the time. He told viewers to “get off the couch,” embrace travel, and “move.” This paean reflected two particular threads of optimism that drove Obamacore: an unvarnished belief that humanity can truly be the better angels of their nature, and a parallel trust in the power of the noble consumer. Later, Bourdain’s perspective would shift during his Parts Unknown period as his personal life grew darker. He reflected a world that was growing darker too.

2013–2015

II. The High Summer of Obamacore

Culture gets sunnier with the slow climb out of the Great Recession, though the shadows grow darker, too, with a greater focus on racist and gendered violence. There’s room for a bolder, more assertive vision of progress — but what’s real, and what’s just for the ’gram?

.

Core Text: Broad City seasons 1–3

It has been said that even the most successful artists are able to command the Zeitgeist for two years at a time. The triumph and curse of Broad City was in capturing that mid-to-late Obama feeling, when the world seemed like a playground for any young person with gumption and imagination. The live-action cartoon debuted in January 2014 two years after Girls and already felt like the next logical step: the same shitty apartments, the same sexual frankness, but with at least the pretense of better racial politics.

.

Anthem: Pharrell’s “Happy”

To describe Pharrell’s 2013 hit song “Happy” by its own name would be to undersell its emotional tenor. All sunny falsetto, gospel harmonies, and swelling hand-claps, the song is relentless cheer bordering on mania. It makes Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry Be Happy” sound like Johnny Cash’s “Hurt.” “Happy”’s path to chart dominance started with the release of its turbocharged, 24-hour-long music video. With its parade of celebrity cameos (Steve Carell! Issa Rae!) and ostentatious flourishes (Bollywood dancers! Stilt walkers!), it doubles as a time capsule and absurd display of economic excess. But the trend Billboard’s No. 1 single of 2014 sparked, in which fans from all over the world filmed “Happy” tribute videos, illustrated the drawbacks of exporting America’s mid-2010s brand of toxic positivity. “Here come bad news talking this and that / Gimme all you got and don’t hold back,” Pharrell sang on the song. Then, as if he’d wished this on a monkey paw, a group of six people in Iran were sentenced to prison and 91 lashes for filming a “Happy” tribute video that violated religious law.

.

Mascots: Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence

Unlike the Schadenfreude-laden train wrecks of the Bush years, the stars of the Obama era were charming, self-deprecating, and somehow more real. Jennifer Lawrence was the most successful actress of her generation, an Oscar winner by 23, with an unpretentious persona that sat in stark contrast to the theater-kid affectations of Anne Hathaway, who suddenly seemed extremely uncool. Chris Pratt was a former sitcom goof transformed into a wisecracking action star through the power of a crash diet. Both were down-to-earth and enjoyably crude, with expressive faces that worked well as GIFs. Together they embodied the era’s parasocial ideal of stardom: Fans wanted celebrities to be the funny best friend they saw on the internet. Their team-up in the sci-fi flop Passengers, released a month after the 2016 election, was an unintentional signpost for the end of the Obama era.

.

Catchphrase: The word “rapey”

In the summer of 2013, the culture’s renewed seriousness around sexual consent came together with the internet outrage cycle and a social-media-friendly tweeness to create one of the decade’s defining buzzwords. “Rapey” was Obamacore in miniature. At its best, it represented a greater empathy for survivors, a lack of patience for masculine entitlement, a desire to move past Aughts edginess. Its downsides, too, were those of the culture as a whole: a winkiness that was at times at odds with the seriousness of what was being discussed; the undeniable whiff of self-flattery as intellectuals got a kick out of divining horrific hidden meanings in songs like “Blurred Lines” and “Baby, It’s Cold Outside.”

.

The Timeline

Orange Is the New Black

As one of the earliest tentpole streaming original series, OITNB offered the promise of infinitely accessible television for the digital age. As a show, it offered a classic trope: the kaleidoscopic ensemble story, where each character’s arc becomes one piece of a larger narrative. As a result, it could be a smorgasbord of threads about social issues, identities, values, and failures yet to be redeemed. Especially in its early seasons starting in June 2013, its vision of failure was often individual, or systemic on the small scale of families, personal choices, or an unfortunate luck of the draw. Its Trojan horse white-lady lead character, played by Taylor Schilling, could virtuously make way for more stories about her Latinx, Black, and gay inmates. (And then she could also come out as bi.) But by the end of its run in 2019, OITNB turned away from what little sheen of optimism it once had. Its villains became institutions, corporate greed, and cruelty fueled by unshakable systemic racism.

Miley Cyrus’s Bangerz era

Back in 2008, Miley Cyrus was still Hannah Montana. By 2013, she had burned her blonde banged wig, been filmed high off her tits on salvia, and released Bangerz, her first album outside of Disney’s Hollywood Records. The music video for lead single “We Can’t Stop” set a new Vevo record for most views in 24 hours and garnered endless dialogue about Cyrus’s cultural appropriation of Black aesthetics (gold teeth, twerking) and use of Black women as “props on the stage of visual pleasure,” to quote Vice’s interview with an African American Studies scholar. This wasn’t the first time that a white artist had borrowed from Blackness to signify rebellion, but this was probably the first cultural moment when said artist was analyzed through the lens of bell hooks’s “eating the other” and aggregated on the Zooey Deschanel–founded blog, Hello Giggles. The pop-outrage industrial complex churned into overdrive that August, when Cyrus performed at the VMAs in a nude-illusion outfit and foam finger, mashing up “We Can’t Stop” with Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” while twerking against her fellow nepo baby. Weeks later, she released her follow-up single, “Wrecking Ball,” beating the Vevo record she had just set and sparking more online outrage over nudity and sexuality, to say nothing of all of the memes and parodies. Does anything sum up 2013 online humor more than Betty White coming in on a “Wrecking Ball”?

Twitter main characters

Twitter was never real life, but the social-media platform inflicted its own tangible justice all the same. The targets were called Main Characters, and the prosecution took the form of mass, and largely anonymous, backlash. The poster child for this phenomenon was Justine Sacco, a communication executive who, in December 2013, was fired mid-flight for popping off a dumb tweet about AIDS before boarding a plane to Africa. To partisans, Sacco’s public humiliation felt like both a coup and evidence for social media’s potential as a moral force. Things are a little different these days with Twitter’s waning cultural power and society’s souring relationship with the internet. But the Twitter Main Character never truly went away, only shifting platforms. Just ask West Elm Caleb.

Childish Gambino

Serving as both a benchmark in the defiant trickle of nerd values and twee aesthetics into hip-hop and a barometer for the sense of bursting possibilities we believed technology was soon to open up for us, December 2013’s Because the Internet — the sophomore studio album and sprawling multimedia exercise from Donald Glover as Childish Gambino — documents a push to turn albums into livable worlds between Ye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy/”Runaway” and Beyoncé’s Lemonade. BTI is the theater kid at bar karaoke who’ll have you know he can nail “6 Foot 7 Foot,” “Marvin’s Room,” and “Itty Bitty Piggy.” It’s the jaded internet-forum poster excited by knowing something you don’t.

Macklemore’s apology to Kendrick Lamar

Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’s The Heist was Grammy catnip: a feel-good independent-label success story involving an earnest white rapper capable of lowbrow braggadocio or sentimental soul-searching and a producer able to meet him halfway. But Heist and the guileless, mindless “Thrift Shop” nabbing three of four rap Grammys instead of Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city and Ye’s Yeezus stunk, sending the ceremony and the winner on redemption campaigns that resulted in fresh voters for the hip-hop awards and a garishly phrased and unwisely shared apology text from Macklemore to Lamar in January 2014: “It’s weird and it sucks that I robbed you. I was gonna say that during the speech.” He spent the next decade working out more pointed uses for his platform, an admirable way to slide down the charts. In time, Macklemore learned to mackle less.

Demolisticles

The chief ideological journal of Obamacore was Buzzfeed.com, where ’90s nostalgia, academic analysis, and quizzes ran alongside conspiracy theories, plagiarism, and image-based posts that read like adult picture books. Most influential on the era’s conception of identity was a series of listicles outlining the key characteristics of increasingly granular demographics — third-culture kids, Bostonians, morning people, children of hippies, 29-year-olds, lesbian Thelma & Louise fans.

The Dear White People movie

The trajectory of Dear White People was indicative of the times itself: a concept trailer with an Indiegogo fundraiser and popular Twitter account turned 2014 Sundance award-winning film — and eventual Netflix show, of course. The esprit d’internet is baked into the script where Sam, played by Tessa Thompson, is the host of a radio show at a fictional Ivy called Winchester University that regularly riles the student body up with her hot takes. Most of the jokes centered on racial microaggressions, similar to the sketches produced on BuzzFeed (then starring Quinta Brunson). Racial humor had a light bite to it — enough to like and subscribe.

Transparent

As one of the earliest TV shows with a major trans character at its center, Joey Soloway’s Transparent became a groundbreaking show in more ways than one: It was in the first crop of Amazon Prime original shows, when the gambit was to pretend there’d be a collective user’s choice in what pilots would get picked up to series. It defined what would become the most distinctive TV form of the Obama times, the sadcom, where it felt safe to put a core feeling of unhappiness and dislocation inside a comedy because the entire country was assumed to be mostly fine. But as soon as it premiered, Transparent, whose central trans character was played by Jeffrey Tambor, a cis straight man, also became a telltale indicator of how far representation had not yet come. And although Tambor won a number of awards for his leading performance, the series’s reputation was damaged in 2018 when he was accused of sexual harassment by two transgender women who worked with him. His firing — and a viral New York Times interview where Jessica Walter cried about how he used to treat her on the Arrested Development set — ensured that whatever progress Transparent made carried the Tambor stain.

RuPaul’s Drag Race goes mainstream

The first season aired in 2009 on Logo TV with a glamorous smear of Vaseline on the lens, hitting its stride around season four (2012) through All Stars 2 (2016) when RuPaul & Co. would establish a baseline of challenges (Snatch Game, balls, sketch comedy, musicals, etc.) and rubrics (“Make me laugh”) that would become the show Bible studied by future contestants. It was the gayest thing on television, because there was a messy, unfiltered quality in those years (“Well, guess what, Mimi, we did,” goes one canonical text) that was only possible because Drag Race hadn’t yet become the phenomenon that would spawn multiple franchises in 15 countries. Season five (January through May 2013) was the inflexion point in the series where the contestants would begin to realize that their time on the show would determine their careers outside of it. This wasn’t a local bar in Kansas anymore.

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby

May 2014’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (subtitled “an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant”) was the painter and artist’s most ambitious work to date. Walker constructed a giant, white sphinxlike sculpture with the exaggerated features of a Black woman in New York City’s old Domino Sugar Refinery and used 80 tons of sugar to create the skin of the piece. The unsubtle way in which it addresses race and labor felt unimaginable in the years leading up to its creation, but the location of A Subtlety — in gentrified Williamsburg — and near-universal praise from white art critics led to several dissenting Black critics who thought the work pandered to a selfie-obsessed population who was only starting to grasp the history of violence in the country.

“The Case for Reparations”

As a sign of how much the Overton window expanded over the Obama era, Ta-Nehisi Coates used the June 2014 issue of The Atlantic to make a serious argument for restitution. A product of rigorous research and a strict materialist lens, the essay outlined how, long after slavery’s end, it was explicit and implicit government policy to extract wealth from Black Americans and funnel it to white ones. “It is though we have run up a credit-card debt and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear,” Coates wrote. In positing “Black plunder and white democracy” as “not contradictory but complementary,” the story set the stage for later writings like the “1619 Project,” which placed racial hierarchy at the heart of the American story. Another sign of the essay’s cultural influence was the way it briefly inspired a trend for saying “Black bodies” in place of “Black people.”

Black-ish

Similar to how Obama not was insulated from racism just because he was elected president of the United States, the Johnsons, the family at the center of Kenya Barris’s 2014 series Black-ish, can’t run from having to reckon with what it means to be Black in America just because they’re rich. This premise, by which the ABC sitcom was marketed, belied the merits of the warmer family sitcom hidden underneath it. But many Black commentators, for whom this takeaway was not a revelation, found themselves asking, “Who is this show for?”

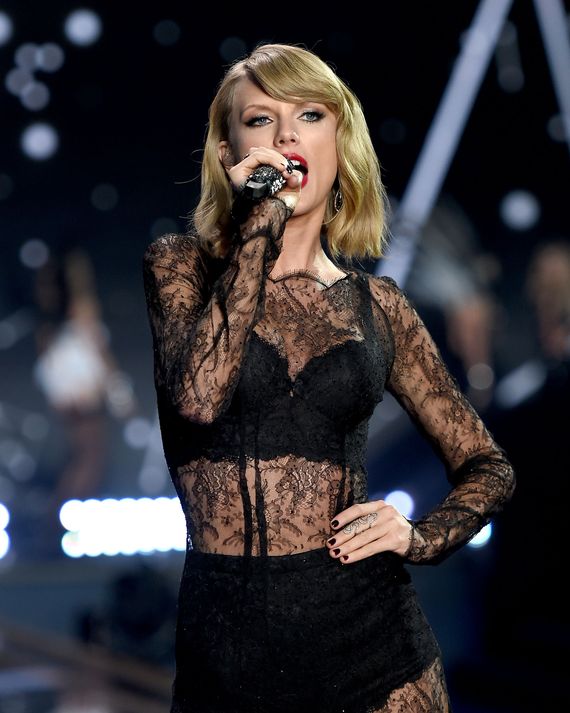

Taylor Swift’s 1989 era

A blue-state carpetbagger who’d infiltrated the most red-state segment of the music industry, Taylor Swift spent her come-up embodying a careful political neutrality. While Jezebel bloggers may have objected, few others did. But in the lead-up to her fifth studio album in fall 2014 — in which she threw off the mantle of country to become a fully fledged pop star — Swift underwent a comprehensive image rebrand. She moved to New York, befriended Lena Dunham, and spoke often about the importance of female friendship and of not being defined by men. She also came out as a feminist, though in characteristic Swift fashion, it was a version of feminism tailored specifically to her — one of its key planks was a woman’s right not to be made fun of at the Golden Globes.

Serial

When it debuted in late 2014, Serial, a spinoff of a public-radio show, unexpectedly drew the attention of hundreds of millions to a single cold case in Baltimore — and a dinky piece of technology called podcasting. Its global popularity launched a thousand conversations about the death of Hae Min Lee in addition to a million other podcasts: about the “power of storytelling,” internet sleuthing, true crime as a moral force as well as a feminist project, and the radical fantasy that this new media format could fix journalism and the criminal justice system. It wasn’t all fantasy, though. Years later, Adnan Syed was released from prison pending an appeal filed by Lee’s family.

Jane the Virgin

It was a show about belief, romance, Latinx culture, ambition, creativity, and a bone-deep confidence that optimism and hard work are enough to ensure that heroes will succeed and villains will fail. Especially at its beginning in late 2014, Jane the Virgin focused on how its characters wrestled with ideas of faith and hope (while also having virgin births, receiving signs from fate, and enduring a series of astonishing telenovela twists). As it moved into its final season in 2018 and 2019, the show became just as much about the external political realities, notably around immigration, that shaped its characters’ lives. And as part of a mini-trend of TV shows about parenthood (including MTV’s franchise-creating docuseries Teen Mom and ABC Family’s The Secret Life of the American Teenager) that centered young people facing adult problems, Jane the Virgin’s narrative broadening earned accolades well into the Trump years.

“Why is your penis on a dead girl’s phone?”

Some context: Before Viola Davis as Annalise Keating, Esq., matter-of-factly utters those nine words at the end of the fourth episode of the series in October 2014, she’s at the vanity getting ready for bed, taking off her wig, peeling off her eyelashes, and wiping off her makeup in a glamorous deglamming. Some more context: Doing all of that was her idea, “like stripping naked in front of an audience and turning around really slowly.” Even more: The New York Times TV critic at the time would call Davis “less classically beautiful,” a dig she would later reference during an acceptance speech. The show arrived at a moment in Davis’s own career when her prominence contradicted her opportunities. That an actor of Davis’s pedigree was finally doing her first turn as a leading lady on a TV show while saying that line with her full Juilliard-trained chest was both an indictment of the industry and a gift of high camp. She would go on not only to win an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series in 2015 but to become the first Black woman to do so.

Winning and breaking the internet

In the aughts, the internet treated its favorite celebrities with quasi-ironic hyperbole; think Chuck Norris Facts, or Don’t Hassel the Hoff. In the 2010s, this relationship grew much stranger. The internet wanted famous people to just kind of stand there, not really doing anything. But if they did so next to each other, or in an unusual environment, it was considered a mind-blowing achievement. Neil DeGrasse Tyson going on Joe Rogan’s podcast, or Kim Kardashian showing her glistening rear on the cover of Paper magazine in late 2014 — each of these things, it was said, had “broken the internet.” The term was an offshoot of a phrase, popular on Reddit, used to describe a viral accomplishment: “You won the internet.” Both spoke to the belief that the internet, diffuse though it was, nevertheless possessed a unified culture. Whether this was true at the time is debatable; in today’s polarized and siloed web, it clearly is not.

#OscarsSoWhite

In January 2015, April Reign tweeted, “#OscarsSoWhite they asked to touch my hair.” The tweet, a response to an entirely white field of acting nominees, went viral, and the Academy’s myopia and disinterest in the artistry of creatives of color, particularly Black creatives, came under scrutiny — which only heightened the following year, when the acting nominees were entirely white again. The Academy responded to the mounting criticisms of their paltry representation with an initiative to make the Oscars’ voting body more diverse, swelling the ranks with hundreds of new members, many of them women, people of color, or international film professionals. As of 2020, the Academy announced it surpassed its goal to “double the number of women and underrepresented ethnic and racial communities.” Whether that has created meaningful change in the industry overall is another matter entirely.

Bruno Mars’s “Uptown Funk”

Bruno Mars sampled pop, folk, reggae, and New Wave sounds early on before achieving immortality with a Mark Ronson feature. A restless aesthete, Mars made an ideal vessel for the big-band funk revivalism of “Uptown Funk,” a time-displaced dance workout that aped synth-friendly ’70s and ’80s acts like the Gap Band and outsold a number of its points of reference. A light vamp suggesting salaciousness without getting into gooey details, another of Mars’s gifts, “Funk” transcended language and topped the Billboard chart in January 2015, though its retro flavor sparked copyright-infringement claims, which were prevalent before pop stars got proactive in crediting accidental co-writers. “Funk” turned the past into a four-minute amusement-park ride no one could resist — not The Ellen Show, the Super Bowl, family reunions, wedding receptions…

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly

Kendrick Lamar’s March 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly was a hearty stew benefitting from several potent ingredients being in season: thriving jazz and beat scenes, a revived West Coast hip-hop apparatus, a championing of artful storytelling and dense lyricism in the face of a tide of less tricky and more melodic songwriting, a national uptick in education on social justice and Black American contributions to the arts inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement. Butterfly tackled sensuality and Chick tract spirituality with the same conviction. “Alright,” the jewel of the album, was a blunt-force blast of a boundless but near-extinct optimism.

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life

Yanagihara’s second novel, published in March 2015, was a massive brick following the manifold traumas of four men with interconnecting lives. The story’s relentless torment of its characters inspired a period of outrage (not a first for Yanagihara) for representing a rebuke to the “It Gets Better” campaign of the early 2010s. Nevertheless, its overall prominence surged thanks in part to a nascent community known as BookTube, an early predecessor to BookTok. Even today, you can bear witness to a new generation of aspiring influencers juicing engagement by filming their own crying faces as they declare A Little Life one of the saddest books of all time.

Keegan-Michael Key as Obama’s anger translator

A lot of mainstream comedy during the Obama years took a reverent tone toward the sitting president, but Key and Jordan Peele’s recurring “Anger Translator” bit from their Comedy Central sketch show Key & Peele might be the most explicit instance of comedians literally doing PR spin on behalf of the commander-in-chief. The bit — in which Obama (Peele) would speak in measured statements and his anger translator Luther (Key) would whip himself into a frenzy saying what he imagined Obama would say if he could speak freely — offered a cartoonish portrait of the double standards Obama faced as the first Black president; he had to retain his temperament at all times or risk reinforcing racist stereotypes. When Key joined Obama at the podium during his April 2015 White House Correspondents’ Dinner address, this subtext became plain. There stood Luther in the crosshairs of presidential politics and respectability politics, defending Obama against the criticisms of the media and adopting the “angry Black man” parlance Obama didn’t believe he could.

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts

Poet and critic Maggie Nelson’s account of her pregnancy and marriage to the artist Harry Dodge — then undergoing hormone-replacement therapy — was an early mainstream entry into both queer and trans literature, one that benefited from providential timing. It was published in May 2015, just after Transparent’s rise in pop culture and right before the Supreme Court’s decision to federally legalize gay marriage. Nelson’s memoir was graphic, plain-stated, and accessible for mass audiences: In the manner that White Fragility and How to Be an Antiracist would popularize “anti-racism” among non-academics a few years later, The Argonauts did the same for gender identity, Judith Butler, and philosophical spats with Jean Baudrillard and Slavoj Žižek.

Mr. Robot

Some Obama-era films addressed the 2007–08 financial collapse, like Inside Job, 99 Homes, and Adam McKay’s The Other Guys and The Big Short. But their condensed, feature-length run times felt like abbreviated history. Enter Mr. Robot. From its premiere in June 2015, USA’s thriller series about a group of hackers taking on the evil E-Corp had a core of bristling contempt, a natural extension of the Occupy protest movement that roiled after the Great Recession. The series’ gorgeously experimental visuals got more attention than its seething populism, but even before the 2017 one-take episode “eps3.4_runtime-error.r00,” creator Sam Esmail’s extreme compositions were always meant to encourage viewers to think outside the box. Right up until Mr. Robot entered another era of Obamacore ideology by giving into centrist capitulation and arguing the status quo was maybe worth protecting, the series was Hollywood’s most meaningful attempt at honoring still-simmering distrust.

The Golden State Warriors

The Golden State Warriors of the 2010s was an avatar for Silicon Valley triumphalism. Games were hot spots where tech execs would go to be seen. Its tech-billionaire owners believed the franchise could Moneyball its way into a forever dynasty. Steph Curry gave the Warriors a joyful face. The team’s rise took place against the backdrop of a country — and a presidency — intoxicated with start-up culture: the app-ification of everything, the deification of tech workers, “learn to code,” Shingy, faith that analytics could “solve” anything from sports to elections. The hype around Big Tech curdled with the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which led to a steady deflation of sunny start-up mania. The Warriors, too, would mirror Silicon Valley’s decline in goodwill. By the 2016–17 season, the team became so rich and unstoppable they were designated as the league’s villains.

Drake vs. Meek Mill

A watershed moment in modern masculinity not unlike Rick Ross dropping the kingpin rap classic Teflon Don after being exposed as a former corrections officer, Drake’s public embarrassment of Meek Mill in summer 2015 after the Philly rapper aired his Canadian friend out for using ghostwriters highlighted a massive shift in fans’ ideals. Meek learned that people don’t care how the sausage is made, and there are no spoils for being right when your opponent has better jokes. Drake, of course, became the immovable heel we know today.

The “Parents” episode of Master of None

The Mindy Project normalized a South Asian comedic lead; Louis C.K.’s FX series Louie, in which he played a version of himself navigating existential crises, was critically adored. And in the overlap between the two flourished Aziz Ansari and Alan Yang’s Master of None. The Parks and Rec colleagues crafted stories specific in their ethnic and racial perspectives and universal in their themes of professional ambition, domestic tension, and millennial ennui, and the series gave Ansari a modern Woody Allen persona that would years later also devolve into sexual controversy. The 2015 season-one episode “Parents,” co-starring Ansari’s parents Shoukath and Fatima, was rich in this era’s ideas: It praised immigration, poked fun at first-gen self-seriousness, and emboldened the romanticized perception of a meritocratic American Dream. The episode’s Emmy win for Outstanding Writing felt like a breakthrough moment for POC creators, and “Parents” remains the series’ most poignant thesis statement.

Creed

Hollywood’s IP era proved amenable to Obamacore — particularly in the form of the “legacy-quel,” a combination follow-up/reboot that allowed old material to be refreshed with contemporary ideas while jettisoning the elements that had aged worst. The high-water mark for this approach was Ryan Coogler’s November 2015 film, Creed. As no less than Muhammad Ali had noted, the Rocky franchise was birthed as a comforting fantasy for white Americans, in which the showboating Black champ Apollo Creed was shown up by a humble white boxer from South Philly. In following Apollo’s son Adonis (Michael B. Jordan)’s battle to live up to his father’s name, Coogler offered a modern corrective to this aspect of Rocky’s legacy. Creed “deftly subverted a cherished American cinematic tradition,” Adam Serwer wrote, “placing Black communities at the center of genres in which they were never meant to be more than plot devices.” That it also featured some of the most thrilling fight scenes ever filmed was a bonus.

.

Swan Song: Ferrante Fever

It wasn’t just that various Neapolitan Quartet novels were pop-y enough to be in everyone’s canvas bags, and it wasn’t just that Italian author Elena Ferrante wrote under a pseudonym, bucking a 2010s impulse to chase celebrity without shame. It wasn’t just that the books covered everything from regional politics to class struggle to sex to maternal regret, and it wasn’t just that it was suddenly cool that everyone was reading books in translation. It’s that Ferrante’s novels, published in the U.S. over the course of four years starting in 2012, unleashed upon us the character Nino Sarratore, the ideal villain for readers already obsessed with stories of complex female friendships winning out over heterosexual love.

2015–2016

III. The Crowning of Hillarycore

It’s all been leading up to this. The final stretch of Obama’s presidency sees the culmination of the era’s specific ethos and the first bridges to the Trump era … plus the short, inglorious reign of “I’m with her.”

.

Core Text: Hamilton

When Lin-Manuel Miranda told the crowd at the 2009 White House Poetry Jam that he was working on a rap musical about Alexander Hamilton, they chuckled at his obvious folly. One presidential administration later, Obama’s unofficial court artist unveiled his opus. When Hamilton opened at the Public in early 2015 (transferring to Broadway six months later), it hit theater like an electric shock, rewriting the nation’s foundational myth as a paean to multiculturalism and immigration. Miranda envisioned Cabinet debates as rap battles, cast a multiracial crew of actors as the Founding Fathers, and, in his not-so-subtle connections between the outgoing president and the first Secretary of the Treasury, posited Obama’s presidency not as a break from the rest of American history but a proud continuation of it. If this necessitated scrubbing away a few unpleasant realities — like how many of its heroes had owned or traded slaves — well, that was only what Obamacore demanded.

.

Anthem: “Sensual Pantsuit Anthem”

Though the Clinton campaign was synonymous with celebrity PSAs, many of these were produced by outside organizations and thus not technically to blame for her losing Wisconsin. Such was the case with the most infamous: Lena Dunham’s “Sensual Pantsuit Anthem,” released days before the election on November 3. A celebrity PSA that was also a parody of celebrity PSAs, the Funny or Die production sought to highlight Clinton’s achievements while also cloaking itself in multiple layers of protective irony. Rapping as MC Pantsuit, a hip-hop version of her “well-meaning, ridiculous white girl” persona, Dunham defended Clinton “from the right and from the left” while a bunch of queer and non-white people told her it was a bad idea. These defensive contortions were all too telling about Clinton’s struggle to rekindle that old 2008 feeling.

.

Mascot: Female Ghostbusters

Women, busting ghosts? Some men treated the July 2016 reboot Ghostbusters: Answer the Call, starring Melissa McCarthy, Kristen Wiig, Leslie Jones, and Kate McKinnon, as cataclysmic blasphemy, an example of Hollywood’s political correctness run amok. The kickback was outsize, and the incel-y rejection of “guy”-coded media featuring women and fan entitlement was everywhere: YouTube, then-Twitter, Rotten Tomatoes. The suggestion that a woman could do anything a man could do in this new, meant-to-be-more enlightened age was kaput, and as geek culture subsumed monoculture, that gender-based division became more entrenched. Think of everything Daisy Ridley went through while playing Rey in the latest Star Wars trilogy.

.

Catchphrase: “Pokémon Go to the Polls”

The 2016 augmented-reality game by Niantic Labs was one of the biggest fads of the decade; it had 232 million users the year it launched, all “catching” Pokémon by hunting them down at real-world locations on the game’s Google-synced map. Who didn’t want to recapture creatures from their childhood in a post-recession state of millennial arrested development? So it was already the perfect surveillance tech for a drone administration when Clinton made a campaign stop in northern Virginia in July. With her arm outstretched in front of running mate Tim Kaine’s face, she said the immortal words, “I don’t know who created Pokémon Go …” [pause for a wide smile and cheers] “… but I’m trying to figure out how we get them to have Pokémon Go to the polls!” In the face of 4chan memelords posting a pestilence of Pepes, it was the best the Dems could do to connect with the youth. The very next day, Trump’s campaign posted a 13-second rejoinder, a Pokémon Go parody called “Crookéd Hillary NO,” with a simple graphic of Clinton getting caught in a Poké Ball. It was Pokémon Go–ver.

.

The Timeline

Competing O.J. Simpson projects

More than 20 years after the not-guilty verdict in the O.J. Simpson murder trial and nearly a decade after Simpson authored If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer, two cable-TV projects running from February through June 2016 tackled the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. One was a well-researched multi-episode documentary about Los Angeles’s racial tensions, infamous police department, and celebrity culture, and one was a Ryan Murphy project that pissed off the victims’ families (this is what all that Glee acclaim wrought). Despite those divergent approaches, O.J.: Made in America and The People vs. O.J. Simpson were both lauded for their attempt to challenge the accepted narrative of this historical moment and probe at our flawed criminal-justice system. And in laying bare how some divisions in this country simply can’t be rectified, they hinted at forces that would shape the election to come.

Zootopia

This animal allegory about a girl cop, released in March 2016, told a story of prejudice and #coexistence in a fantasy metropolis where anthropomorphic mammals have evolved past the need to eat one another and instead live and work together in neighborhoods built around their differences. There are gags about animal microaggressions (it’s rude to touch a sheep’s hair, it’s offensive to call a bunny “cute”) and stereotypes (sloths are slow, rabbits breed like … rabbits). The plot revolves around a conspiracy to frame predatory animals — who are a minority at 10 percent of the city’s population — as violent, which leads to overpolicing. You don’t need a master’s degree in critical race theory to guess that a metaphor rooted in inherent biological differences amounted to some messy messaging. (Nonetheless, a St. Paul police department used the film in its annual anti-bias and equity training.) But what makes Zootopia a true piece of Hillarycore is its theme song, “Try Everything.” Shakira voices a sexy gazelle pop star named Gazelle who performs surrounded by hunky shirtless tigers and whose signature single is “Fight Song” meets “Roar.” It’s grrrrrrrreat.

“Equal Rights” from Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping

Credit where it’s due: Making a would-be gay empowerment anthem about marriage equality then more or less disclaiming “no homo” four lines into it is a good bit. Unfortunately, when Macklemore did this in his 2012 hit song “Same Love,” he wasn’t joking. Still three years out from the national legalization of same-sex marriage in America — a cause Obama campaigned against in 2008 — the silly gay panic of “Same Love” was mocked less than its good intentions were celebrated. By the time the Lonely Island released their mockumentary Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping in May 2016, though, all bets were off. “I’m not gay, but if I was I’d want equal rights,” Samberg raps in character as Conner4Real, before reaffirming his heterosexuality dozens more times. Cut to Ringo Starr sitting down for a talking-head interview about the song’s performative nature: “He’s writing a song for gay marriage like it’s not allowed. It’s allowed now!”

Insecure, Atlanta, Fleabag, and The Good Place

The seeds sown with shows like Girls and Transparent finally came to full bloom in the fall of 2016, when TV comedies reckoning with cultural disillusionment rocketed onto the scene. The expressions were different. Insecure was the SATC-esque youthful discovery comedy shifted by its setting in a Black American experience and by the creative force of Issa Rae, whose early career was in online media rather than well-paid newspaper-column writing. Atlanta was a story of American striving and creative success, now rooted in the unshakable consciousness of financial insecurity and racial discrimination. Fleabag, a British show, drove the quirky lead comedy protagonist to the inevitable end point: a trauma that fuels her charming oddness. And The Good Place, source material for the single most succinct, blunt-force articulation of this entire period in American culture: Everybody thought this was The Good Place. It’s actually The Bad Place.

.

Swan Song: Kate McKinnon performing “Hallelujah” as Hillary on SNL

Saturday Night Live let Donald Trump host in November 2015 during his presidential campaign. After his win the following year, SNL’s November 12 cold open was a mea culpa. While Kate McKinnon performed Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” as Hillary Rodham Clinton, the mood was somber, the crowd silent. There was no gag, just three minutes of television that served as a funeral for HRC’s white pantsuit and all the morality and competency her followers believed it represented. When a teary-eyed McKinnon turned to the camera to say “I’m not giving up, and neither should you,” the statement took the shape of a reassurance and an appeal. Yet it also felt like the moment in which all the (presumed) hope, potential, and sincerity of this time curdled into self-pity. With this line drawn, there was no allowance for the suggestion that maybe the Obama years weren’t as successful in delivering on their progressive promises as they should have been. And with that final exclusionary turn, the movement that initially presented itself as so much more reached the end of its era.