There’s a reason “As if!” and “Four for you, Glen Coco” are embedded in the memories of today’s ex-adolescents for all eternity: Teen movies hit people “at an incredibly malleable, influenceable time,” as filmmaker Charlie Lyne explains. His new documentary about the genre, Beyond Clueless, premiered this week at South by Southwest. Narrated by Fairuza Balk (everyone’s favorite teen witch), it deconstructs cliques, party scenes, and devirginations, while also serving as an irresistible guide to the best (and worst-best) teen movies ever.

The Cut talked to Lyne about the genre’s unexpected depth, generational changes, and the significance of pubic-hair pizza.

Why did you decide to make a documentary about teen movies?

About a year and a half ago I was asked by a cinema in London to program a teen-movie film festival. So I started revisiting all these films that I’d been obsessed with as a teenager, and watching them all back to back. It was amazing for two reasons: I realized how real that nostalgia was, and that the emotion they’d had was still there. But there was all this stuff that I’d never noticed in them before. All these seemingly simple films that now seemed incredibly odd or sinister or deep. Whether there was sort of a sexual undercurrent or a larger message about what it is to be an individual or an adult or an adolescent, it all suddenly came through.

How many films did you watch in total?

About 300.

What are the hallmarks of the second golden age of teen movies (as you call it) as opposed to those of the classic 1980s ones?

For me, the marked difference is mainly the diversity of these films. I mean, I have a massive affection for the 1980s school of teen filmmaking, but actually there were very few films that kind of defined that time. And what I love about the ‘90s and ‘00s teen movies is that there aren’t really canonical ones — there were so many being made. Between 1995 and 2004, you had a teen movie coming out every single week, and they were all incredibly different.

But don’t all teens just want to be the same?

No, no — what are teenagers if not incredibly diverse? The whole idea of cliques is based on this sense that teenagers aren’t all after the same things and are divided by their clashing desires. They should have characters to identify with and a massive spectrum of films to pick from. Maybe you like American Pie or Cruel Intentions — all these films existed in the same space, and yet they’re so vastly different.

There’s still the same basic structure, though — a party, a love scene, a makeover scene.

Absolutely. People know there’s always the party, there’s always the graduation. But there are some things that make you think, I had no idea this could be in every single teen movie. For example, the late-’90s way of meeting the main boy or girl — that introduction is in almost every movie.

And you chose to structure your documentary by mimicking those tropes?

We tried to completely embrace the world of the teen movie as well as deconstruct it, so our film is structured like a teen movie. It starts with everyone arriving back at school for the beginning of the school year, we go through the teen house-party, we go through the first flirtation, and then the virginity-losing scene and prom night and graduation. We cover the whole arc, using specific films to create an analysis of that journey.

Why have these films endured? I still watch Jawbreaker regularly.

Jawbreaker, the worst reviewed movie of [1999] — and yet it still lives on for so many people (me included) as a weird document of the time. How few genres are there that define what age you will see them at? They’re hitting people at an incredibly malleable, influenceable time. It’s when people are most ready to find their analog on-screen and work out who they are through what they’re seeing. The amazing thing about talking to people about the films is it’s actually not Clueless and Mean Girls and the big box-office hits that people want to talk about, it’s the one film that people had on VHS when they were 16 that they watched 100 times that still lives with them.

What’s an example?

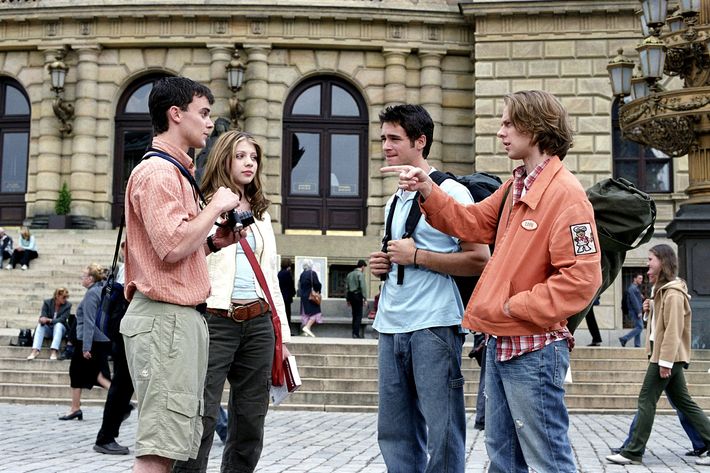

The movies that I find the most fascinating are not the most unequivocal classic movies. They are partially great and very confused. I like the films that hint at something brilliant but are off-kilter. For me, that’s EuroTrip. I was amazed at what was going on in the film unbeknownst to the film. While it’s supposedly about teens taking a trip through Europe to chase a girl, it is also about a guy’s desperate grasping for a sense of identity. He goes around the world trying to meet with his heterosexual love interest, but what he does is enact wildly homoerotic scenes. And that is never mentioned. It never would have occurred to me as a teenager.

EuroTrip did get away with some raunchy stuff. A lot of those movies did — like the pube pizza in She’s All That.

This is the other thing I love about teen movies: You can get away with weird, psychosexual stuff that would never pass in a straightforward drama or comedy or anything else, because it’s under this veneer of: Oh, it’s a teen movie, it doesn’t mean anything. Like the scenes in Jawbreaker where she’s with her jock boyfriend and she makes him fellate the ice lolly. In any other movie, this would be like a plot point and we’d have to get to the bottom of it. What’s wrong with him? Is he gay? What’s up? In this movie, it’s just like, Nah, just teenagers, experimenting, testing the limits of their sexuality. Whether or not the film realizes it, a wealth of stuff is going on beneath the surface. Even if they didn’t have a sinister edge, there seemed to be a deep vein of unspoken reality to the films.

I don’t know — I love the teen movies I watched growing up, but were they actually any good?

I think this is exactly the point of teen movies. Personally, now that I’m not a teenager anymore, I’m very glad that I don’t understand modern teen movies because I think that’s a sign that they’re working. So there are plenty of teen movies recently out that I like, but actually I think that’s less important than the teen movies that adults seem not to like. Project X wasn’t a movie that I particularly enjoyed, but the fact that it caused such upset and outrage and became a real talking point shows that teen movies for this generation are finding their own voice, and aren’t just imitations of movies before. They should be something that a generation has that isn’t understood by the older generation. Stuff, like Project X and Spring Breakers, that’s really working for modern teenagers, even if it’s confusing a lot of adults — it’s perfect. It’s doing exactly what it should be doing. I hope that means that the genre is back.

But Spring Breakers is by Harmony Korine. Critics loved that movie. People had, like, hours of intellectual debate about it! That doesn’t really count.

You get that all the time with the teen genre: People feel the need to determine whether something is worthy. As much as Harmony Korine would say, This is not an ironic, sarcastic, satire movie; this is me wholeheartedly endorsing this world, critics would still be like, It’s a satire! It’s a satire of the MTV generation, oh, definitely. Whereas younger audiences were taking it much more at face value — how the director claims it was intended. If it hadn’t been directed by Harmony Korine it would’ve been written off, even if it was the exact same movie, because critics would’ve gone in expecting just some trashy teen film. It’s like Virgin Suicides, which is also in our documentary: I think it’s a mistake to necessarily divorce them from the wider genre just because they’ve got a respected name behind them or an Oscar nomination.

Give me your list of Teen Movie Superlatives.

Favorite Teen Movie of All Time:

EuroTrip. When I was 14, it meant being able to see a naked woman on-screen and laugh at some jokes that seemed very taboo at the time. When I was 19, it was the film where I first started thinking, God, this is really weird. How did I not notice this stuff when I was younger? And, ultimately, it was the thing that kick-started the whole idea of making the film.

Favorite Party Scene:

Can’t Hardly Wait. I think house party movies shouldn’t work. It shouldn’t be fun to watch people having fun. I think the balance between those stories works so perfectly.

Favorite HBIC:

Rose McGowan in Jawbreaker. Purely because one of the reasons that movie slightly falls down is that it’s so enthralled to her. And quite justifiably. Because she is incredible.

Favorite Sex Scene:

This veers between a few tonally disparate examples: the depressing, collegiate ennui of Rules of Attraction (when Van Der Beek fucks Kate Bosworth); the intense, romanticized fantasy of The Dreamers (mainly Eva Green’s virginity-losing scene); and the absurd, OTT farce of Jim and Michelle’s eventual union in American Pie.

Favorite Romantic Interest:

Judy Greer in Jawbreaker. Judy Greer, for me, was always the stereotypically dowdy “nerd girl” pre-transformative makeover. Her endless locks of matted hair and stack of comically large textbooks always do it for me.

Favorite Male Heartthrob:

Ryan Phillippe, Cruel Intentions–era.