This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

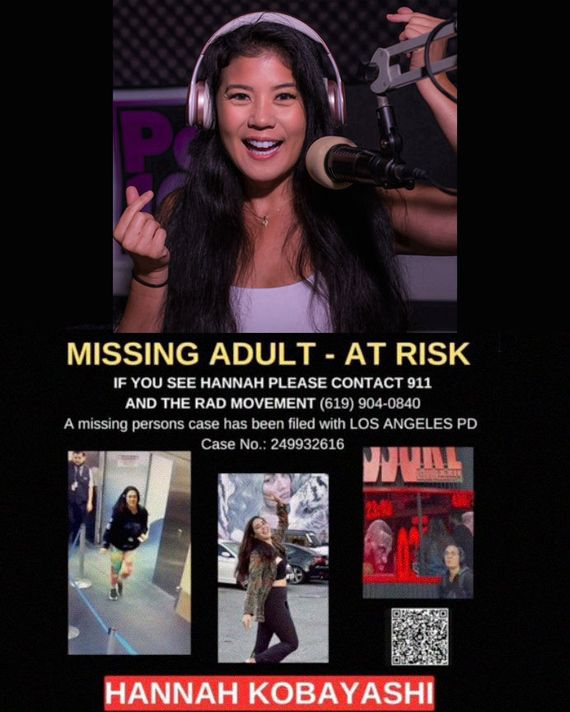

On the afternoon of December 2, 2024, Jess Chou, a radio-advertising executive in Honolulu, sat at her computer waiting for the livestream of a Los Angeles Police Department press conference. The police were scheduled to give an update on the case of Hannah Kobayashi, a 30-year-old Maui woman who vanished three days after missing her connecting flight from LAX to JFK on November 8. Just before Kobayashi’s phone went dead, she sent friends and family a series of strange texts. She said she’d been “hacked” and “stripped of my identity”; when asked to explain, she said, “I got tricked pretty much into giving away all my funds. For someone I thought I loved. I’ve been on the streets.” The messages, Kobayashi’s family said, didn’t sound like her, and Chou feared that she had been drugged, abducted, trafficked.

Chou didn’t know Kobayashi — she had learned about the case on the local news a few days after she was reported missing. But Chou saw parts of herself in her: a woman in her 30s who lived in Hawaii and liked to wander. “I thought, Shoot, I travel a lot. What should I be looking out for? ” Chou says. Curiosity soon turned into obsession. She stayed up past midnight reading news articles and joined a private Facebook group comprising hundreds of people in L.A. who strategized about where to look for Kobayashi, checking off each location on a custom Google map of the city. The group’s members took shifts monitoring webcams of Skid Row, installed by a downtown L.A. shelter, where some thought Kobayashi might be staying; Chou watched for hours.

Within ten days of Kobayashi’s missed flight, an army of enthusiastic online sleuths had joined the search, lighting up countless message boards as they swapped theories and alternative timelines. Like most millennials, Kobayashi had left a vast digital footprint, which strangers could scour for anything that resembled a clue. Chou nearly memorized the images on Kobayashi’s Instagram grid, a collage of lush landscapes and artful selfies with captions alluding to magic and manifestation and quotes like “Attachment is the root of all suffering.” She combed through Kobayashi’s Spotify playlists and Pinterest boards, which contained DIY wedding ideas, guides for how to “live on next to no money,” and tips for making a “secret six-figure side hustle.” (Had Hannah gotten roped into a get-rich-quick scheme gone wrong? Chou wondered.) She even perused Kobayashi’s most recent Venmo transactions, one of which said “reading” and another that had a bow-and-arrow emoji, both made shortly after she landed at LAX. (Chou assumed the former was for an astrology reading; for the latter, “people were messaging me that it means ‘drugs,’ but I don’t know.”)

When the December 2 press conference finally began, the LAPD chief revealed that he had obtained surveillance footage from U.S. Customs and Border Protection. One week earlier, in a public meeting, he’d said that Kobayashi had intentionally missed her connecting flight to JFK — a finding that her family publicly rejected, suggesting that the police had been sloppy with facts as basic as Kobayashi’s age. Now, the LAPD had proof: The video from CBP “clearly shows” Kobayashi walking from California into Mexico on foot, the chief said. Not only was Kobayashi alive and seemingly unharmed, she was also alone and in possession of her luggage. According to the police, she had disappeared entirely of her own volition. The missing woman wasn’t missing at all.

To some, the news marked a resolution, albeit an anticlimactic one. Websleuths — an old-school message board where devoted members dissect grisly cases like the University of Idaho murders and JonBenét Ramsey’s death — decided to shutter its missing-person thread on Kobayashi. But her family held its ground. Kobayashi’s sister, mother, and aunt again challenged the LAPD, insisting they couldn’t be sure that Hannah was actually in Mexico by herself. They resolved to keep looking.

Many amateur investigators weren’t ready for the case to be closed, either. From its start, they’d been consumed not only by the mystery of the missing woman but also by the cast of characters it had brought together: an eccentric van-life influencer aunt, who appointed herself the media spokesperson; a conservative anti-trafficking activist tapped by the family to chase down tips; a skeptical PI not officially hired by anyone with a knack for surfacing bombshell revelations. In public and behind the scenes, they — along with other members of the family — had spent weeks feuding and contesting one another’s tactics, findings, and theories, which only spurred further theorizing and conspiracymongering among those following the case from home. It was like watching a reality show called Keeping Up With the Kobayashis, Chou thought, but it was a show whose stars she and others could interact with in real time. And even though the lost woman had been declared found, the viewers who’d faithfully tuned in wanted to see for themselves.

When Kobayashi moved from Oahu to Maui in the fall of 2020 at age 26, it marked the start of a new chapter, her first time living away from her family and the beachside enclave where she had grown up. With a friend, she launched a floral-design venture that involved scavenging for plants and flowers in the jungles and forests just beyond her house. She paid the bills with an assistant-manager job at a smoke shop and, on days off, practiced meditative dance that involved twirling a staff lit on fire at both ends. “So grateful to have found the outlet of movement and expression through flow art,” she wrote on Instagram beneath a photo of her fire-dancing on the beach.

In 2024, Kobayashi planned a trip to New York City. She’d booked it with her boyfriend, but by the time it rolled around, they had broken up. They decided to keep their flights — it was cheaper than rebooking — and part ways once they landed. In an itinerary that her family later shared with news outlets, she’d written out a bucket list for her week in the “Big Apple”: After landing on the morning of November 9, she was considering going to the Brooklyn Folk Festival that afternoon, followed by a techno show at Knockdown Center in Queens that night and an Afrobeat show at Webster Hall the next day. In addition to the usual tourist spots (MoMA, Central Park, the Brooklyn Bridge), she planned to spend time with a maternal aunt who lives in the Hudson Valley.

Kobayashi landed at LAX just before 10 p.m. on Friday, November 8. Her connecting flight to New York took off 42 minutes later; she wasn’t on it. “Are you in NY? Love you!” her mother texted her the next morning. “Not yet,” she responded.

Her mother sensed that something was wrong. She texted her sister in the Hudson Valley: Had she heard from Hannah? But her daughter hadn’t texted anyone in the family, and her phone was going straight to voice-mail.

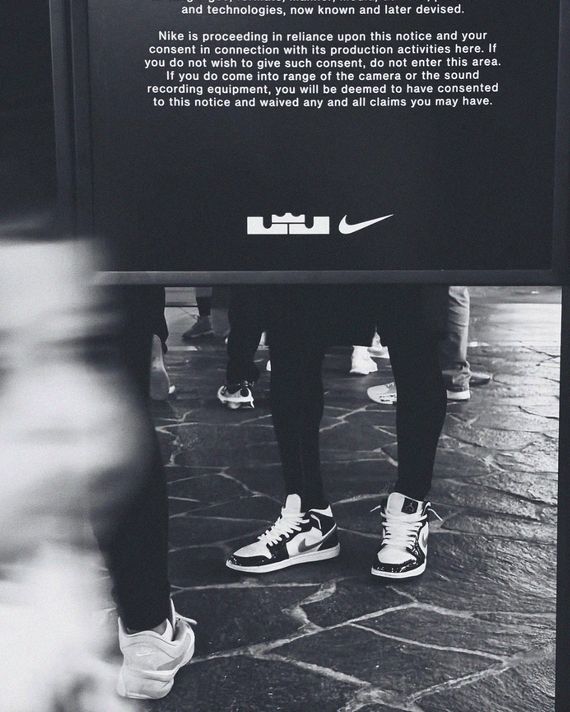

On Sunday, November 10, Kobayashi posted a photo to Instagram. It shows a fragment of signage from a Nike pop-up event at the Grove, an upscale outdoor shopping mall near West Hollywood. To the post, she added the Sam Cooke song “A Change Is Gonna Come.” The day after, she sent the messages claiming she’d been hacked and was on the streets. “I just need to rest & I’ll think better … But it’s very complicated,” she wrote. When her friend asked if she had been catfished, she replied, “Matrix underworld shit girl. This is way beyond me.”

“Did you get catfish by some dude you were talking to on the Internet?” her friend pressed. “No, we met,” Kobayashi replied. “I can’t explain all of it. Just please be open with this please.” Then her communication stopped.

Within a few days, her father, Ryan Kobayashi, from whom Hannah was estranged, flew from Oahu to L.A. to look for her. Meanwhile, her mother, Brandi Yee, and her 32-year-old sister, Sydni Kobayashi, sat for interviews with local news stations in Hawaii. Sydni created a GoFundMe to raise money for the family’s travel and publicity efforts in L.A.

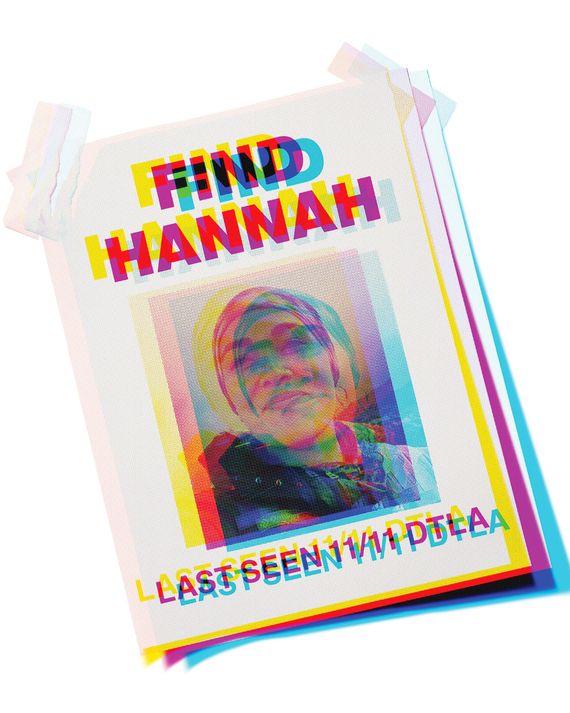

From Big Sur, inside a renovated 1997 RV decorated with Southwest-style rugs and macramé wall hangings, Kobayashi’s other maternal aunt, Larie Pidgeon, sounded the alarm too. Pidgeon is a van-life influencer based in the Pacific Northwest; on TikTok, where she has nearly 200,000 followers, she makes vlogs sprinkled with pep talks about opting out of the nine-to-five grind and paeans to the open road. She and her niece were similar in that way — a week before Kobayashi’s trip, Pidgeon had texted her, “Meditate and write down all your thoughts and dreams. Speak them into existence.” Now, to her followers, Pidgeon posted a missing-person flyer and a montage of photos of Kobayashi, a pretty brunette with warm brown eyes and a silver nose ring. The flyers quickly began circulating on Websleuths and missing-person accounts on X.

At Pidgeon’s urging, Kobayashi’s mother filled out an intake form with a missing-person nonprofit called the Rad Movement, founded by a 51-year-old San Diego woman named Sharie Finn. Finn, who drives a large pickup truck and wears a Louis Vuitton monogrammed bag and scarf, says she started the group after her special-needs daughter was abducted from high school in 2021. “She went missing for five days and was trafficked here in San Diego,” she tells me. Since then, Finn has become something of an anti-trafficking crusader; she says her small team of volunteers has handled more than 80 missing-person cases, including those involving the children of B-list celebrities like The Real Housewives of Orange County star Tammy Knickerbocker.

Soon after taking the case, Finn got a tip from someone who claimed to have seen Kobayashi with a man on a Metro train in South L.A.; the two later got on a different train and were seen exiting near the Crypto.com Arena downtown. “In that area, there’s a lot of characters you can encounter that are nefarious and up to no good,” says Finn. She’d been speaking to Kobayashi’s mother and sister on the phone, and they described her as someone kind and caring but not necessarily street-smart. “They said, ‘If a street person came up to Hannah and said, “Do you have a cigarette?” Hannah would give them her last cigarette and her last $20,’” says Finn. The family also believed that she could have been in a mental-health crisis.

On the morning of November 15, Pidgeon and her husband drove down to L.A. in their RV to look for their niece. Upon arriving, Pidgeon began doing interviews, too. (Kobayashi, along with the rest of her family, declined to participate in this article.) In the studio with CNN, Pidgeon said she and her family were starting to accept a painful possibility. “Our mind is now going to abduction, and I hate to say the word, but trafficked.” Then she issued a desperate plea to whoever she feared may have taken her niece. “If someone has Hannah, I want you to know that she is the kindest, most beautiful soul in the entire world,” Pidgeon told CNN. “Please don’t hurt her.”

Disappearance-Reappearance Timeline

Erin Paris first learned about Kobayashi’s disappearance from a Facebook post. Paris, a 40-year-old photographer, had moved to the L.A. area from Oahu just a few months earlier. She knew Kobayashi, so she figured she was uniquely positioned to lead a local search effort. She doesn’t remember exactly how they met, only that it was about a dozen years ago in the Honolulu suburbs, where they both grew up. “Hannah was like my hippie hometown friend,” Paris says. She changed her profile picture to an old photo of the two of them together and created a Facebook group to organize volunteers. Paris knew that Sydni Kobayashi had already created one (called Help Us Find Hannah), but that group had ballooned, enabling “armchair investigations” that Paris didn’t feel were helpful. “My group” — Find Hannah Search Team — “was strictly about trying to pass out flyers and following up on tips,” Paris says.

On Thursday, November 21, Paris teamed up with Larie Pidgeon and Ryan Kobayashi to host a rally to draw more press coverage. Speaking to a sea of reporters outside the Crypto.com Arena, Pidgeon, bawling, repeatedly warned that her niece was not alone and that she may be in danger. Ryan stood beside her, looking scared and emotional. In an interview with a Fox News station, he expressed regret over his estrangement from his daughter. (Court records show that Kobayashi’s mother filed a temporary restraining order against him, citing domestic abuse, when Hannah was just a baby. Ryan had limited visitation with his children at the time, and it’s unclear how long he and Hannah had been out of contact.) “I just wish that I could’ve been there more for her,” Ryan told the TV cameras. “And now you are,” the newscaster offered, but Ryan didn’t seem convinced. He looked away, then said, “I’m trying,” before his voice trailed off and his eyes welled up. Eventually he finished his thought: “Trying to find her is everything.”

But at search-party headquarters, rifts were starting to form. Sharie Finn, who was also in frequent contact with Pidgeon, felt wary of her motives. She “kept saying, ‘The narrative, the narrative, we have to stick with the narrative,’” Finn says. “I was like, ‘We don’t work with narratives; we work with facts.’” Her distrust only grew, she says, after learning from Sydni that Hannah barely had a relationship with Pidgeon. “She’s a distant aunt that she connected with via phone just a few months before this happened,” says Finn. Finn also worried Pidgeon’s appearances on the news — which she found “histrionic” — were encouraging amateur detectives and transforming the case into a made-for-TV spectacle. She says Hannah’s mother and sister shared her concern. “They asked her to stop: ‘You don’t need to be doing all these interviews. We have no facts; we need to just find her.’”

Sydni realized she needed to get to Los Angeles. “The sister said, ‘I’ve got to get out there because this is turning into a damn circus,’” Finn remembers. Sydni arrived in L.A. shortly after the rally. According to Finn and another person with knowledge of the situation, Sydni and her relatives — including her other maternal aunt and uncle, who had flown in from New York — got into a heated argument about Pidgeon that Saturday night.

At around six the next morning, Finn says, she got a call from Sydni, who was at the hotel she had been staying at with her father near LAX. “She said, ‘My dad’s gone. I don’t know what to do,’” Finn says. “She went downstairs; he wasn’t down there. And she’s like, ‘His phone is here, his wallet’s here, everything’s here.’ So I said, ‘Okay, hang up with me, call the police.’”

But the police had already been called. About two hours earlier, a security guard at the parking garage near the hotel had dialed 911 after airport travelers told him there was a man’s body lying on the ground outside. The man had no personal identification. Copies of a missing-person flyer with Hannah’s face on them were scattered around him.

L.A. County medical examiners determined that Ryan died by suicide after jumping from one of the top floors of the seven-story parking structure. (Security footage captured his fall.) According to the autopsy report, a person close to Ryan told the LAPD that he had been “declining mentally each day” since he’d arrived in Los Angeles. The night before, Ryan paced around the hotel room in severe distress. One of Ryan’s family members told the authorities that Ryan had felt guilt for “not being a better dad.”

Steve Fischer, a 55-year-old private investigator specializing in missing-person cases, had met Ryan Kobayashi just a few days earlier, when he showed up to the rally to offer his professional assistance. Fischer lives in the area but frequently travels out of state for work; he was curious about the case, he says, “because it was literally in my backyard.” At the rally, he noticed, Pidgeon repeatedly referred to a piece of surveillance footage of her niece exiting a downtown L.A. Metro train with an “unknown person” and claimed that she appeared to be in distress. It seemed dangerous, he thought — fearmongering. He worried it could lead to someone getting hurt. (The family never produced the footage, and the LAPD later announced it had interviewed the man, whom it determined was not a suspect.)

Fischer started to suspect that the high-profile missing-person case was not a missing-person case at all. He thought about how Pidgeon had mentioned to reporters that Kobayashi stopped by the luxury-art-book store Taschen during her trip to the Grove; she even added her name and address to the mailing list. “ She’s at a high-end shopping place, not in distress,” Fischer remembers thinking. At the rally, he says, a volunteer from Paris’s Facebook group had shown him surveillance photos of Kobayashi picking up her suitcase from a baggage claim at LAX on November 11, three days after she landed in L.A. It suggested to him that she’d intended to stay in the city and made the decision willingly. And it led him to a controversial hypothesis, further informed by the free-spirited captions he saw on Kobayashi’s Instagram. “There is a strong possibility that Hannah is seeking time alone and may be exploring a spiritual path,” Fischer wrote on X the day after the rally. To his 25,000 followers, he announced that he was stepping back from the case (then he clarified that he hadn’t actually been hired to work on it).

A few days later, he received a voice-mail from Pidgeon. “I’m just trying to clarify, like, how you’re involved, or what’s going on, because we’re really trying to control our narrative,” she said. “We’re just really, really confused because it’s an ongoing investigation, and from our contact with the LAPD, they don’t know who you are.”

Without identifying Pidgeon, Fischer tweeted about the voice-mail, which he found bizarre; like Finn, he was disturbed by her use of the word narrative. That, coupled with the sudden tragedy of Ryan’s death, was enough to persuade Fischer to reengage. The death, he says, “doesn’t make sense to me. I deal with a lot of families, and I’ve never seen that happen before, even when we found their loved ones deceased.” He decided that “welcome or not, I’m going to jump back in” — even if it meant taking time away from the cases he was being paid to investigate. Within a week, Fischer had gotten in touch with a person who knew Kobayashi from home. They leaked him screenshots of a group text that contained a photo from the Instagram account of a blond man named Alan. The photo, taken on a beach, depicts Alan and Kobayashi, who is wearing a white dress and a purple lei.

On November 29, Fischer described his latest finding on X in a multi-paragraph post: Kobayashi, he was now confident, wasn’t being trafficked. However, he riffed, “there are questions that need clarification: Is Hannah legally married to Alan?” Fischer’s sources had informed him that Alan was from Argentina. If the two had married, he wondered, was the marriage “for green card purposes?” He added: “While I believe the marriage aspect may add complexity to her story, it does not seem directly related to her being missing.” (Fischer based this theory solely on the leaked Instagram photo, and marriage records are not public in Hawaii. Reached via Instagram DM, Alan did not respond to questions about the alleged marriage.)

Online sleuths pored over the new development. “Who the fuck is Alan?” Chou said on Thanksgiving Day in one of her near-daily TikTok updates from Honolulu. She tracked down the new character’s social-media accounts and quickly formed a picture: He was a surfer who, like Hannah, was fond of nature, travel, and electronic music. He had gone to college in Buenos Aires and moved to Maui a handful of years ago. (On Facebook, he’d checked into a bar near Hannah’s house in January 2020, shortly before she moved there.) And like Kobayashi, he frequently posted shots of island landscapes with captions like “into the spell” and “what we do in life echoes in eternity.”

In a thread, Chou and others also pointed out that Alan’s name appeared in the handwritten New York City bucket list Kobayashi’s family had given news outlets. According to the document, she had been planning a “shoot w/ Alan” at Central Park and to take “photos together” at MoMA. On Reddit and TikTok, theories blossomed: that Kobayashi had planned to take the photos for the purpose of faking a loving relationship, for example. Or that she’d been paid to marry the Argentine man because she was having money troubles, as suggested by the Pinterest boards she’d titled “money making jobs” and “money saving strategies.” They also pointed to a photo Kobayashi had posted on her own Instagram the day before her expected New York flight of a purple lei, its flowers slightly faded. The caption read “hell have no wrath~like a womxn” — was this a sign, they wondered, that the plan had gone awry and that she was seeking revenge?

They were a generation of close readers trained on true-crime podcasts and documentaries, empowered by the endless trail of data that now follows everyone in the form of social-media updates and surveillance footage. They’d grown used to having access to evidence — early in the case, Kobayashi’s family had shared the itinerary, along with a trove of text messages and photos — but now that they’d started putting the pieces together and finding holes, they began to wonder if the family itself was intentionally misleading them.

“Someone has to know who Alan is, guaranteed, in their little circle,” Chou said on the Thanksgiving-Day TikTok. Her reasoning: It was Kobayashi’s family that had shared with news outlets her travel itinerary, which contained his name. In another TikTok, Chou zoomed in on a news photo of a finger on the hand photographed holding the itinerary and wondered whom it belonged to. “Here it is zoomed in — look at it. Particularly the nail bed, where the cuticle is.” Her theory was that whoever was holding the itinerary knew about Kobayashi’s alleged marriage — and maybe they had other information they’d been withholding, ultimately thwarting the public’s efforts to solve the mystery, for reasons that were themselves a mystery. (Kobayashi’s family maintains that they didn’t know about any alleged marriage prior to her disappearance.)

Sleuths and content creators began badgering everyone involved in the case. They left angry comments in Sydni’s and Paris’s respective Facebook groups, on Kobayashi’s Instagram posts, and on Pidgeon’s TikToks, demanding explanations for everything from the alleged marriage to Kobayashi’s father’s death to the GoFundMe, which had raised tens of thousands of dollars for purposes that were, to many critics, hazy.

On Reddit, commenters questioned the legitimacy and political agenda of the Rad Movement. They pointed to the nonprofit’s logo, a riff on the 18th-century Gadsden flag with the words don’t tread on our children printed below the graphic of the coiled rattlesnake. They tracked down Sharie Finn’s former media appearances, including one from April 2024 in which she told the New York Post that she carries a Glock in her purse in part because of her concerns over undocumented immigrants committing crimes. “They’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re a bunch of radical conservatives!’” says Finn. “It’s like, yeah, I love Jesus. I love America, and I am conservative, but we’ve recovered kids that are gay, we’ve recovered trans youth, we’ve recovered Black, we’ve recovered white. We help anybody.”

Initially, the Facebook group started by Erin Paris, Kobayashi’s hometown friend, was a place where locals found community — “I’m not, like, the most extroverted person, so this has been a way to not only make friends but also, to be honest, explore the city,” says one of the volunteers, who had moved to L.A. early in the pandemic. Now, sleuths infiltrated both Paris’s group and Sydni Kobayashi’s, where they gained access to Hannah’s family and friends. “There’s some Zeitgeist psychosis — people unhappy with their lives and seeking attention — that this case has tapped into,” Paris says. “It gives them camaraderie, like they all know the truth and they’re all working together.” Paris started banning people, including Chou, whose posts she felt were too probing. Some of them began questioning how close Paris had really been to Kobayashi, after discovering the two hadn’t spoken in six years. They were also suspicious of Paris’s decision to delete a TikTok she had posted early on about Kobayashi’s disappearance; she’d done so because “not all my facts were straight,” Paris admits. “I’m a human, and I’ve changed my mind on things. There was a time where I said there was no way Hannah was not mentally healthy because I’ve always known her to be very grounded. But I understand that sudden-onset mental illness is a thing.”

The online criticism had begun to take a toll. Paris’s weekends were filled with client photography sessions ahead of Christmas-card season. “I’m getting messages where people are saying that I should go to prison because I’m one of the reasons that Hannah’s father killed himself and then going to little babies with my little squeaky toy,” she says. Hannah’s sister, Sydni, was fed up with internet commenters too. On December 1, she shut down the Facebook group, citing threats made against her and her family’s lives.

The following day, Fischer tweeted another revelation. He’d learned from a Greyhound employee that Kobayashi bought a bus ticket on November 12, more than a week before her family held the rally that activated search parties all over the city. Fischer announced that Kobayashi boarded the 6:35 a.m. bus from Union Station to San Ysidro, a border crossing between San Diego and Tijuana. The LAPD press conference, held just hours later, officially confirmed Fischer’s findings.

Kobayashi’s family wouldn’t let it go. After the press conference, Sydni and her mother hired a private investigator and announced they were focusing their search on Mexico. (They were still working with the Rad Movement, but Sharie Finn was unwilling to take her team south of the border, citing safety concerns.) They also retained a criminal-defense attorney. The decision, unusual for a missing-person case, spurred more speculation: Could the lawyer have been hired because the family had been implicated in a green-card scheme? (The LAPD clarified at the press conference that Hannah “is not a suspect in any criminal activity.” The department also hasn’t accused anyone tied to the case of wrongdoing.)

In a NewsNation TV interview, Sydni and her new lawyer, Sara Azari, who is also a frequent TV-news commentator, argued that they hadn’t seen the footage of Kobayashi crossing into Mexico and didn’t believe that she would have done so voluntarily. “They say that they’ve seen her alone, but that doesn’t discount the fact that someone could be watching her from afar, knowing how big this case has gotten, and maybe controlling her or telling her what to do,” Sydni told Hawaii News Now.

Fischer and many of his amateur counterparts thought that Kobayashi’s family had been wasting their time and resources as well as those of law enforcement and the media. “People turned on those internal Facebook groups with the family really quick because they felt betrayed,” he says. In an attempt to cast doubt on the family’s statements, he tweeted out the screenshot of the group text a source had sent him. As it turned out, the photo from Alan’s Instagram account, of Hannah in the white dress and purple lei, had been shared in the group chat by someone with Sydni’s name and photo. “This cannot be released yet,” “Sydni” had texted. “But this is our confirmation and lead now.” In the text thread, she explained her theory: that Hannah’s ex-boyfriend, who had somehow teamed up with Alan, was extorting and trafficking Hannah.

“We want to stress that the family has not publicly announced any information regarding an alleged marriage because we did not have the facts or the necessary documents to verify the legitimacy of this information,” Azari announced on X that night in a statement on behalf of Kobayashi’s mother and sister. The statement called it “one of many leads we are actively investigating” and said that Kobayashi’s mother and sister turned over materials they had found allegedly supporting the marriage theory “to law enforcement immediately upon receipt.” To this day, the family is also in the dark about the alleged marriage; in an email statement, Azari said, “The family does not have any confirmation of the marriage or any immigration petitions related to the same.”

The family’s public statement on X also explicitly disavowed Pidgeon, who had appeared on TMZ earlier that day to talk about the LAPD press conference. “While we appreciate Larie’s efforts, she does not speak on behalf of our immediate family, which consists of Hannah’s mother, Brandi, and her sister, Sydni,” it read.

Pidgeon also announced that she was no longer coordinating with her sister and niece. (Or, as she recapped it to her TikTok followers, “We are splitsies.”) She said she was planning to go to Mexico to look for Kobayashi herself and had recently become aware that “someone named SF Investigates,” referring to Fischer’s X handle, “said on here publicly that they know where Hannah is.”

Chou was mesmerized by the sparring between Pidgeon and Sydni. And when Chou saw Pidgeon’s latest TikTok, she texted and then called her. (Earlier, the two women had connected on social media and started communicating behind the scenes. Chou says she was also in touch with Sydni, serving as a kind of self-appointed family mediator.) “I told Larie, ‘You need to reach out to Steve Fischer,’” Chou recalls. She gave Pidgeon his contact information.

Pidgeon texted Fischer. (“ I can tell she didn’t put two and two together. She didn’t realize I’m the person she called and who left that message for her,” Fischer says.) He texted her back about the tip he’d gotten, giving her the name of a residential gated community in Rosarito, about 20 miles south of the U.S. border.

Meanwhile, Kobayashi’s mother was also planning to go to Mexico to look for her daughter. On December 10, Finn, from the Rad Movement, went to the San Diego airport to meet her. The plan was to drive to the U.S. Consulate in Tijuana to ask to review surveillance footage of Kobayashi crossing the border on foot. It was a week after the LAPD press conference, and her family still hadn’t seen the evidence with their own eyes. Finn offered to drive the Kobayashi family to their hotel in San Diego that night, and she was with them the next day, she says, when they got a frantic call from Pidgeon in Mexico. “She was screaming, ‘I have Hannah, I have Hannah, I have Hannah, I have Hannah,’” says Finn, who heard the call on speakerphone.

Kobayashi’s mother, according to Finn, asked to speak with her daughter. But when Hannah got on the phone, she sounded quiet and removed; she wouldn’t say where she was or where she had been for the past month. “Mentally, she does not sound well, and she sounds like she’s reading notes that people are maybe writing,” says Finn. “There’s long pauses in her conversation and then she’ll answer something, and the way she answers it is very much in the way Larie speaks.” (Finn thinks it was too easy for Pidgeon to miraculously find her niece in a different country in a matter of days. “I think she knew where she was the whole time, but that’s just my opinion,” she says.)

The missing-person case, though now considered voluntary, was still technically active. So to help interface with Customs and Border Protection, Pidgeon enlisted the help of Doug Kari, a 69-year-old lawyer, freelance journalist, and occasional true-crime author who had interviewed her for a news article. Kari, too, had gotten sucked into the case: He’d spent 14 hours the previous weekend sifting through the profiles of Kobayashi’s roughly 1,000 Facebook friends to see if any of them lived in Mexico and might have information about her whereabouts. When Pidgeon called him on December 14, he drove down to the border from his home in Southern California and took a taxi to meet Kobayashi. On December 15, they walked over the border back into the U.S. He says he didn’t ask Kobayashi anything about where she’d been or what she’d been through. “I didn’t see that as my mission,” he says. (Later, his brief involvement made people wonder if Kari was working on writing a book or securing a content deal with Kobayashi, but he says that’s not true. The reason he went, he says, is because “it seemed like an adventure.”)

A day after Kobayashi’s return to the U.S., Pidgeon shared a statement that she attributed to her niece. “My focus is now on my healing, my peace and my creativity,” it read. “I was unaware of everything that was happening in the media while I was away, and I am still processing it all.”

Months later, many questions remain. Was Kobayashi ever really missing? What was the “Matrix underworld shit” she referred to? What was she doing in Mexico, and did she know that her father had died? In the absence of satisfying answers, some armchair detectives have been left feeling swindled. For months, Chou felt like she was trying to unlock the next level of a game, only to learn there was no prize at the end, no answers. “We dedicated so much time in trying to help them, and in return, it’s like we got slapped in the face,” she says.

Throughout, onlookers have projected their own fears and fantasies onto every aspect of Kobayashi’s journey. In the darkest version of it, Kobayashi had been trafficked or worse. But to others, she was a folk hero, a millennial woman who had managed to opt out of a culture where surveillance is ubiquitous, connectivity is constant and demanding, and everyone is expected to be reachable by phone at all times. After they found out she was in Mexico, some onlookers sent Kobayashi “taco money” and cash for “tequila shots” on Venmo, celebrating her apparent escape and affirming to her that she didn’t owe anyone an explanation. “She fucking escaped. Good for her,” said a friend of a friend from Oahu. She says she admires Kobayashi and has wanted to find a way to leave Hawaii, too. “Artists are struggling. The housing is so expensive. The jobs are not paying well. Just to find a job is tricky, then you gotta hustle.”

As of mid-December, according to a since-deleted Facebook post, Kobayashi’s sister and mother still had not seen her in person. In the post, Sydni Kobayashi defended her family’s actions and announced that she was turning off donations on the GoFundMe, which had raised more than $42,000. But she, like the rest of the world, is still waiting to “get the answers we truly deserve,” she wrote in the post. (Six weeks later, on February 5, she announced that the money was being donated to two organizations: one dedicated to finding missing children and another focused on suicide prevention.)

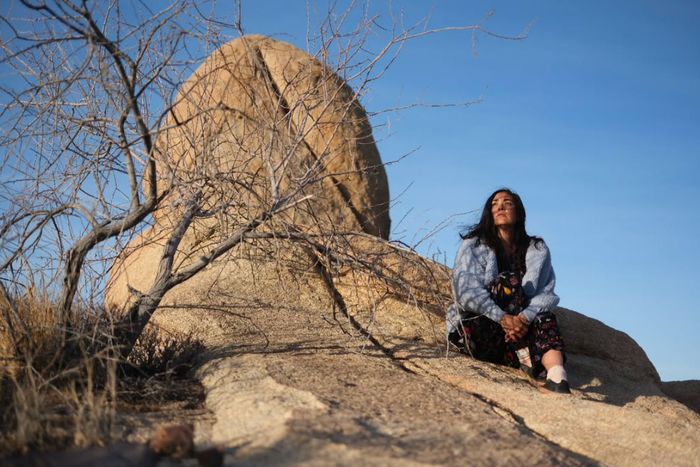

Another mystery that remains concerns Pidgeon — how she found Kobayashi and whether she knew her whereabouts for much longer than she let on. (“that is the million dollar question,” the lawyer Sara Azari said in an email statement on behalf of Kobayashi’s mother and sister. “The family does not know.”) Was it a strange viral hoax? Those answers don’t appear to be coming anytime soon. After announcing that she was headed to Mexico, Pidgeon took a 20-day hiatus from social media. Upon her return, she posted an Instagram Story announcing she was in Joshua Tree, California, and had no interest in talking about what had happened with her niece.

The same day, Kobayashi seemingly resurfaced, too. A photo posted to a new Instagram account shows her sitting on a boulder in the desert. It’s geotagged “Joshua Tree, California.” The caption: “When the whole world is looking to you for answers, what would you say?” She wrote and then later deleted from the caption a series of follow-up questions: “How would you feel if your entire existence was put on display? For the world to judge you without knowing your truth? To say you are at fault for your father taking his own life? Are we so quick to put a magnifying glass at the life of another, that we forget our humanity?”

Correction: Doug Kari returned to the U.S. from Mexico with Hannah Kobayashi, not Larie Pidgeon, and met Pidgeon on the other side of the border.

More From the 2025 Spring Fashion Issue

- Jessica Simpson and Ashlee Simpson Talk New Music, Heartbreak, and Prince

- Top of the Crops

- What Your Status Home Décor Says About You