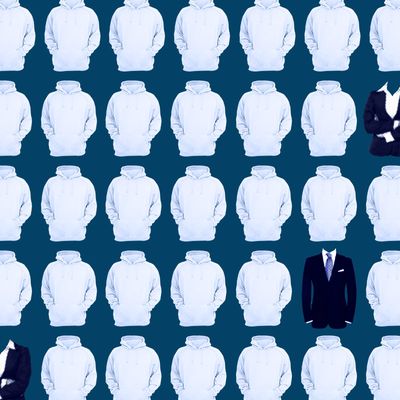

Palmer Luckey is the founder of Oculus VR, a start-up that Facebook bought this week for $2 billion. He is 21 years old. His company makes virtual-reality headsets, which are marketed primarily to gamers. In fact, several Oculus staffers are people Luckey met in online-gaming forums when he was a teenager. On the “Careers” section of Oculus’ site, large candid photos depict what one can only assume is that staff. They are overwhelmingly male. They are overwhelmingly white. And yes, a few of them are wearing hoodies. In a statement at the bottom of the page, Oculus avers it is “governed on the basis of merit, competence and qualifications,” and its hiring decisions are not influenced by race, gender, or age.

It’s been a full decade since Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook and launched a thousand breathless trend stories about the code-fluent, post-adolescent masses flocking to Silicon Valley to change the world in Adidas slip-on sandals. But this youthful uniformity, once considered a feature, has become a bug. Tech, the the New York Times confirmed this week, has a “youth problem.” Writes former Facebook staffer Kate Losse, “Silicon Valley fetishizes a particular type of engineer — young, male, awkward, unattached.” Or, as the New Republic put it, the tech industry’s “brutal ageism” means that if you don’t fit the archetype — say, you’re over 35 and only wear hoodies when you’re exercising and have a few kids and a mortgage — you have to work twice as hard to get ahead. They’re stressed out and ostracized by the “culture,” worried about their wardrobe choices, wondering if they should freshen up with some subtle plastic surgery, and struggling all the while to downplay their family lives.

While I empathize, I found myself stifling a yawn as I read the Botoxed bros’ tales of woe. I’ve heard all of these stories before. It’s just that the storytellers are usually women.

If you think putting on a hoodie is rough, I wanted to tell these guys, try finding the line between workwear that’s not too sexy but also not too schoolmarmish. If you’ve reluctantly taken up gaming in order to bond with your co-workers, now you know what it was like for women who learned to golf so they could meet male clients on the course. And ask any woman who’s ever huddled in her office hooked up to a breast pump: It’s not always so easy to be casual about the fact that you’ve got kids. Or the fact that you’re different. (Most of this stuff goes doubly and triply for people of color and gay people and those with disabilities.) Welcome, men, to the world of being hyperaware of how you’re perceived, every moment of every workday.

Older men in tech are discovering the unseen work that women and people of color have done for decades. Fitting in is hard work — an additional, invisible task on the daily to-do list. “I had a really hard time getting used to the culture, the aggressive communication on pull requests and how little the men I worked with respected and valued my opinion,” Julie Horvath, a whistle-blowing former employee of the programming network GitHub, told TechCrunch. For most of recent history, we’ve made it women’s responsibility to fit in. Despite the prevalence of equal-opportunity disclaimers, actual corporate culture isn’t changing fast enough (or at all), so it’s on women to figure out how to succeed in workplaces that are not overtly sexist but still quite alienating. Think that sounds retro? In another article this week, the Times offered some time-honored advice to women: “Moving Past Gender Barriers to Negotiate a Raise.”

Rather than offer tips to older male entrepreneurs, the chroniclers of Silicon Valley ageism make a case that the industry is what needs to change. The tech world, which counts innovation and creativity among its core values, has created a culture of unparalleled uniformity. The appearance of daring (look — that co-founder is so young he doesn’t even need to shave every day!) has proved more alluring than actual diversity of background and experience. And this casual discrimination has been bad for business. Both pieces point out that consumers lose as a result of the industry’s narrow view of who’s got good ideas. The Times points out that Silicon Valley is missing all sorts of opportunities in the hardware sector because software is sexier to young entrepreneurs.

When it’s men who are confronted by biases, we look at the bigger system. When women are, we put the onus on them to get ahead. And when it’s people of color facing bias? Well, that story is so familiar it barely makes headlines anymore. Journalists are paying attention to ageism in tech because it’s a new story that older white men, traditionally a very powerful demographic in the white-collar world, are struggling with how to succeed in a collarless culture that claims to reward merit but rejects them due to factors beyond their control.

Maybe Silicon Valley has inadvertently produced an innovation here: It’s “disrupted” discrimination, to use the industry parlance. The tech-ageism stories, with their focus on culture rather than explicit policies, provide a new way of seeing the now-familiar stories about Silicon Valley sexism — and indeed, general workplace sexism, too. In most cases, companies aren’t actively alienating women. They’re rewarding people who match their deep-seated archetype of what “successful” looks like.

That’s a difficult thing to undo with an equal-opportunity hiring policy. Just ask the shocking number of gay people who are still in the closet at companies that have received awards for their LGBT-friendly policies. Or the women who dread telling their supervisors that they’re pregnant. Or take a look at the Oculus recruiting page and compare the text with the photos. Maybe now that a major industry is excluding a traditionally powerful group (older white men), it will be easier to recognize that other groups’ failure to break into the highest ranks of corporate and political power isn’t a result of personal shortcomings or lack of ambition — it’s a cultural problem.