“Margaux worked harder at art and was more skeptical of its effects than any artist I knew,” Sheila Heti writes in her novel, How Should a Person Be? about the character Margaux — who is based, quite closely, on her real-life best friend, Margaux Williamson. The actual Margaux is a painter who lives in Toronto, and her most recent work is the subject of a new book, I Could See Everything, out this month.

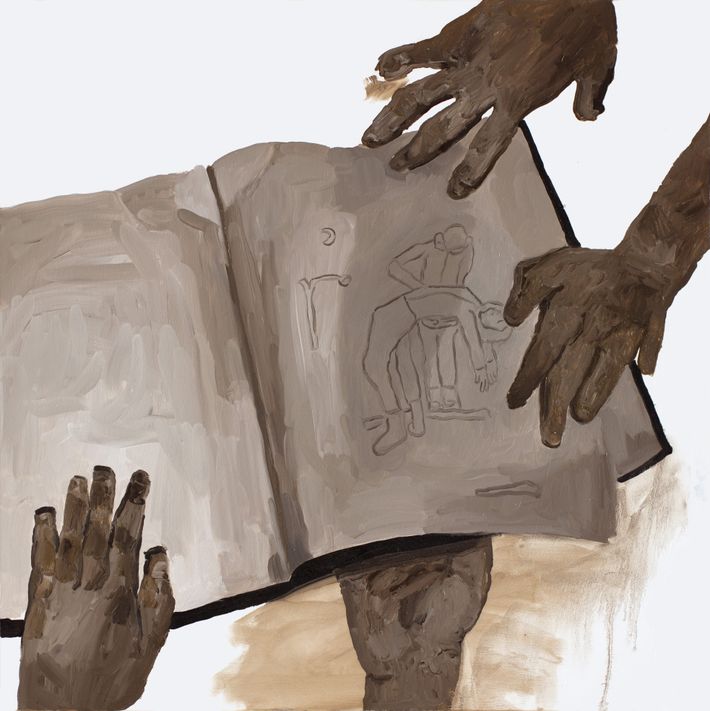

First conceived during a trip to the Yukon in 2009, the work in the book spans five years, and plays with the relationship between imagination and the real world. In fact, the book’s conceit is that it’s a collection of paintings for the imaginary Road at the Top of the World Museum, curated by Ann Marie Pena.

“I thought, if it’s a book, then it gets to be any institution that I want,” said Williamson. “And, I was working with a real curator who was taking her role very seriously. She told me why the museum wanted to have me, and she was so straight-faced. It was so fun. I was like, Wow, I’m making my own art world.” Williamson’s paintings are both playful in approach and ambitious in scope, grappling with the existential questions that consume her: whether painting can be meaningful and what it might mean to be able to see “everything” (“even the person with the greatest eyes can barely see anything,” she concedes in reference to her title). She spoke with the Cut about humility, narcissism, and finding meaning in art.

In the book, you say that you start all your paintings with text sketches. Have you always worked that way?

When I started painting, I’d work on, like, ten canvases at once, for maybe like a year, and I just worked on them over and over again. This process somehow naturally came out of that, where I figured out that if I write things down and do a lot of the work in my head beforehand, it just saves a lot of time and paint. I’m not good at drawing, so I just take notes. None of the notes are actual painting ideas, they’re just thoughts or something I overheard or something I can’t get out of my head. I keep them all in a box, so when I’m doing the “art part,” I take that box and see if there’s any order to be found in it. With my old notes, a lot of it’s garbage and I throw it away, but sometimes it’s a much quicker way of seeing if there’s any natural order to your random imagination and line of thinking.

In an interview with Chris Kraus in the book, you say that as you became less interested in yourself, it became more useful to use yourself as a character. How did that start to happen?

Around 2006, I started working with Sheila Heti quite a bit. We were both in a similar place — we actually work in a very similar way. We are both pretty intuitive artists. Anyway, we both sort of stopped working a little bit and just starting talking to each other, and that turned into a book for her, and for me, I ended up making a movie. I didn’t know how to make a movie, exactly, but I had all these strong urges and desires, and a real burst of inclination came out of me to do that. You know, I don’t know that much about narrative or storytelling, but I realized the most helpful thing for a viewer would be to know why I was making this and where I was going with it. It was helpful, being in Sheila’s book, to see the outline of myself … it all just seemed like, Oh, that’s the most helpful thing I can do as an artist — I can say who I am and what I’m looking at. For me, my paintings in the past were always a bit more narrativesque than they look now, but now they’re much more literally a narrative, because the narrative is: I’m a painter, and I’m trying really hard to do something. Which is sort of like as simple of a narrative as you can get.

In an interview with The Believer, you said: “Art’s not immediately meaningful to me, and the act of doing isn’t automatically meaningful to me, so I feel like I have to struggle really hard to find meaning.” It feels gratifying to hear an artist say that.

Oh, really? Is that unusual, do you think?

I was going to ask you that! But yeah, I think it feels unusual for someone to say that so directly.

Well, I’m so happy to hear that resonated. Sometimes I feel so frustrated with myself, like, Don’t say that one more time! [Laughs.] But I think that makes a doctor a good doctor or a gardener a good gardener — the idea that you don’t trust that what you’re doing is great, or that the craft you’re handed is perfect, or actually genuinely meaningful in the world. I think that no matter who you are or what you do, it’s pretty good to reexamine the bones of your livelihood. I think it’s also a gift for some people to never have to question that — like if they’re raised thinking art is this gift they were given, that must be really nice, and maybe it even helps them make art in some ways. But I feel lucky that I think like that, because it is a genuine joy for me to try to find meaning and find how things fit together — and to have hope that you can maybe see a more elegant structure than the one you’ve been handed.

With Chris Kraus, you were also talking about anxiety about being misunderstood, and how lately you “learned that being understood isn’t the most important thing.” What changed?

Honestly, I feel like I get through things just by having a lot of fear. Being in Sheila’s book was pretty terrifying. I think that being a character in my work or other people’s work, it’s humbling. I’m sure some people see it as narcissistic, but for me it’s primarily humbling, because it’s like, Look, I’m just this person here, and I have no interest or hope in ever communicating my full essence — or anyone else to do that. I just feel like everything gets to be complete for what it is. All those things are so fragmented, but they’re still real.

Sheila was working on that book for four or five years. I think it started when I was 27, 28 — that’s an age where you’re still a teenager, in our prolonged adolescence, and you like, like, Oh, I can still do everything. Like, I can be this useful person in the world, or I can still be this or this. The hardest thing for me was just being like, Oh, I’m an artist. Like, that’s what I am, that’s what all my actions communicate — I mean, that’s very true. But when I saw that I was like, Okay, you’re an artist — you better just be really an artist, then. It was a slight corrective help.

How did you decide on the title I Could See Everything?

It’s related to the humbleness of having to only feature your own eyes, and only communicate through your own eyes and hands. It’s such a big claim, like, I could see everything, but it’s also so small — like, I can see what I can see from this small place where I am standing. I guess there were a lot of things, like looking up from yourself and really trying to look at the world, and also the feeling of being in the Yukon — you have the sense that you can see everything, even when you’re so far away from the world — and how we are all like that now, how we can see so much, no matter where we are. And how great it is and also how awful it is to see everything when you are so far away — like being that type of god that sees everything and does nothing. Also, it’s willful — as though I could see something that’s not necessarily true and make it true, since I saw it somehow. It’s a claim. It’s a lot of things, but I’m happy whenever I see the title. I’m like, That’s the right title! It’s helpful that it’s just “I,” you know?

A selection of Williamson’s paintings will be on view at the Frith Street Gallery in London from July 4 to August 16.

I thought I saw the whole universe (Scarlett Johansson in Versace)

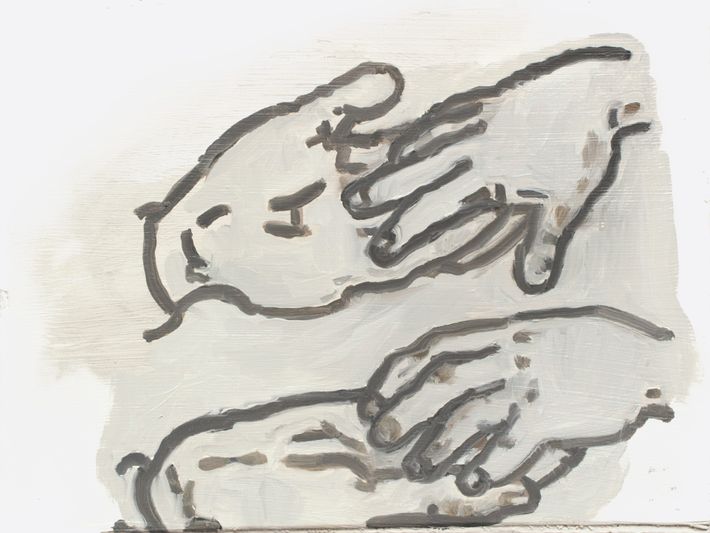

We were really very happy for their love

We loved the world and the things in the world

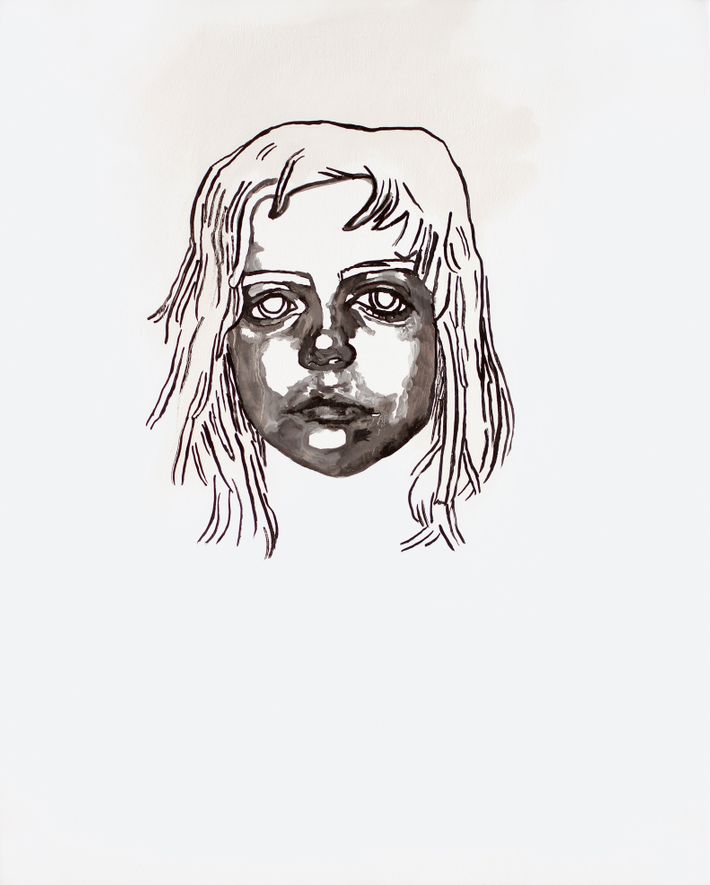

At night I painted in the kitchen

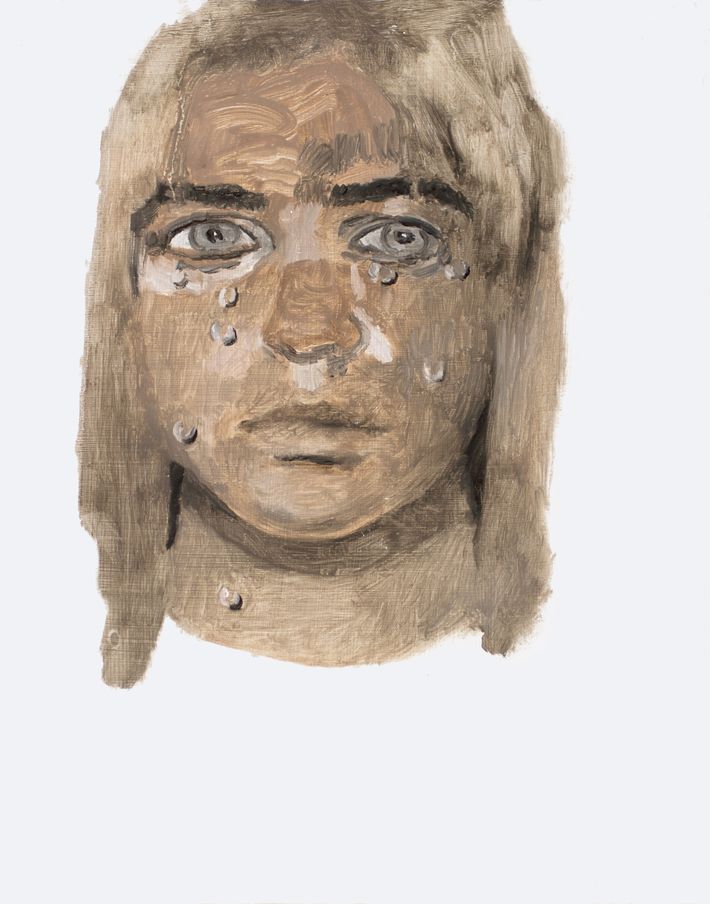

Painter

We got lost on the way home

I made that same drawing too

I could see everything

We built a new city with our shadows (Lynn in the boat)