A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences claims to lend support to the popular but controversial notion of “emotional contagion” — that is, the idea that happiness and sadness and other emotional states can spread through social networks. The findings are suspect, but more eye-catching are the study’s venue, Facebook, and its research subject: you. (Well, maybe.)

Working with Facebook, the study’s authors grabbed two big groups of the site’s users — more than 600,000 in total. For one of the groups, they dialed down the frequency with which positive posts written by their friends appeared on their news feeds; for the other, they did the same thing but with negative posts (as always, users could still see all of their friends’ posts by clicking on their profiles). Users in the fewer-happy-posts group subsequently posted in a more negative manner, the researchers write, while users in the fewer-sad-posts group did the opposite, suggesting that good and bad moods were effectively transmitted through the Facebook network.

The results don’t really hold up to much scrutiny, though, for reasons laid out very nicely by John M. Grohol. Read his post if you want the gory details, but it comes down to the facts that (1) Posting something positive isn’t the same thing as actually being in a good mood; (2) The researchers used a seriously flawed textual-analysis method that would rate “I am not happy” as a positive posting because it can’t parse the “not” in that sentence; and (3) The actual effects the researchers found, while statistically significant, were really, really small.

But people are reacting more to the privacy implications than the research finding, anyway — some folks are freaking out that they were served up manipulated versions of their news feeds, possibly making them (ever so slightly) happier or sadder.

On the one hand, it’s understandable to have a visceral reaction to secretly being the study of a psychological statement — yeah, there’s something creepy about this. But on the other, when you actually look at how Facebook’s news feed works, the anger is a bit of a strange response, to be honest. Facebook is always manipulating you — every time you log in. Your news feed is not some objective record of what your friends are posting that gives all of them equal “air time”; rather, it is shaped by Facebook’s algorithm in very specific ways to get you to click more so Facebook can make more money (for instance, you’ll probably see more posts from friends with whom you’ve interacted a fair amount on Facebook than someone you met once at a party and haven’t spoken with since).

So the folks who are outraged about Facebook’s complicity in this experiment seem to basically be arguing that it’s okay when Facebook manipulates their emotions to get them to click on stuff more, or for the sake of in-house experiments about how to make content “more engaging” (that is, to find out how to get them to click on stuff more), but not when that manipulation is done in service of a psychological experiment. And it’s not like Facebook was serving up users horribly graphic content in an attempt to drive them to the brink of insanity — it just tweaked which of their friends’ content (that is, people they had chosen to follow) was shown.

If you use Facebook, you’ve given the site consent to mess with your news feed. This was good enough for all of the relevant ethics boards. Susan Fiske, the Princeton researcher who edited the study (and who said herself that she found it a little suspicious), hit the nail on the head in her interview with Adrienne LaFrance of The Atlantic:

“I was concerned,” she told me in a phone interview, “until I queried the authors and they said their local institutional review board had approved it — and apparently on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time … I understand why people have concerns. I think their beef is with Facebook, really, not the research.”

Exactly. Many of the folks most outraged by this seem to be Facebook users (I can tell because they are venting their outrage on Facebook), so if they find this sort of behavior to be unconscionable, they should think twice about using the site.

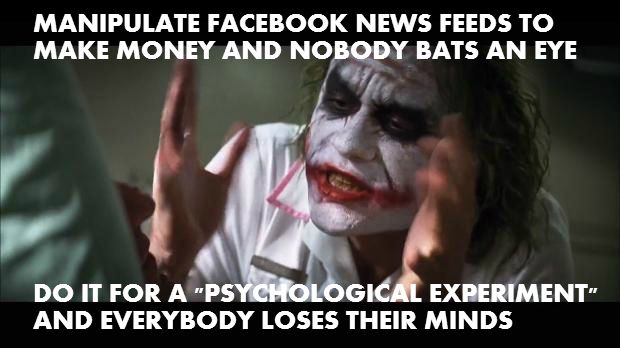

Anyway, the Joker naturally has some strong feelings about this: